9.4: Barriers to Counteracting Climate Change

- Page ID

- 76852

In principle, climate change and its consequences can be counteracted through prevention, mitigation and adaptation. As it stands, opportunities for prevention, although abundant throughout the 20th century, have been largely missed; at this stage we can only prevent the worst any more. This is sometimes included in the area of mitigation, which also means that the impact of climate change is lessened. In contrast, adaptation efforts focus on developing ways to live with the consequences as they occur. As the climate crisis unfolded, the spectrum of most effective countermeasures shifted from prevention towards mitigation and adaptation.

So what are the barriers to mitigating the climate crisis and to adapt to its outcomes? Scientists have shown that the many years of gathered and modeled data make the main answer uncompromisingly clear: stop burning fossil fuels, or anything else. The carbon dioxide that comes from burning fossil fuels makes up the majority of the greenhouse gases that are causing climate change. These emissions come from the major sectors of energy, waste, residential and commercial buildings, industry, transport, and agriculture, land use, and forestry (IPCC, 2014a). Curbing emissions from these sectors will require a mix of top-down governmental pressure, and bottom-up demand from citizens and civil society. Climate change is a problem that does not recognize political or geographical boundaries, and thus presents a unique situation in which cooperation from all sectors, all countries, and all people, is required. It also makes it that much harder to solve. In this section, the major barriers to a climate solution are examined.

Technological Barriers

In order to reduce emissions in all sectors, sources used for energy must be low in emissions, or have no emissions altogether. Thermonuclear energy is generally not considered among these options as it entails its own unique set of environmental problems. That leaves industries in the renewable sector. These renewable energy sources include solar, geothermal, wind, and hydroelectricity. Following this solution, mitigation of emissions from abatement technologies, land use change and agriculture should also be addressed. Because of the pressing nature of climate change, all solutions must be pursued, but solving the climate crisis inexorably requires a global transition to clean, renewable energy use.

The transition to the use of renewable energy will not be simple and will require a coordinated effort between many stakeholders. Take, for example, British Columbia’s major source of heating fuel for residential and commercial properties. Natural gas is supplied by five natural gas thermal plants that extract from four fields (Whiticar, 2017). A transition to a renewable thermal energy supply would require an overhaul or redesign of the distribution infrastructure that is currently in place, whether that is geothermal heating, solar thermal energy, or using electric boilers or heat pumps (Boyle, 2004). In addition, a transition away from natural gas would affect those with a vested interest in the industry – including shareholders, workers, and policymakers. It will require a well thought-out, just, and equitable transition plan that takes into account training for workers in renewable energy jobs, assistance to natural gas companies in the transition, both financially and operationally, to renewable energy technology. The ongoing disputes about pipelines illustrate the difficulties.

The technology required to get the world to 100% renewable energy is already available – and is the focus of a few studies globally[11][12]. More funding and resources should be devoted to testing this model’s capacity to serve a growing population. In addition, scientists and policymakers alike should continue to conduct research and development to advance to renewable energy infrastructure capabilities (i.e. number of people served, improved storage capacity, etc.)

While there is ample public support for renewable energy technology around the world, cultural resistance still exists in many communities. Many people feel resistant to a renewable energy transition because they fear it will change the way they live, or greatly affect an important socio-cultural practice in their lives. This reluctance is supported by conservative media and opinion engineers that tend to enjoy ample funding and political support. They pervade and partially shape our culture.

Culture and Society

While the environmental movement has certainly picked up steam over the last few years, it has not yet moved into the mainstream. Culturally, there are several reasons people have not integrated sustainable habits into their lifestyles. Culture refers to the socially accepted norms and behaviours people engage in, and differences are found from country to country, region to region – between neighbouring cities, and even down to the level of neighbourhoods. These behaviours and norms include the values, attitudes, beliefs, ideals and priorities that children acquire from an early age.

The most prominent reason humans do not opt to change their habits is the ease of retaining and using longstanding, well-established systems and modes of behaviour (status quo bias). To change that can often be time consuming or costly, and sometimes both. For example, sorting through your garbage bin to separate the various recyclable materials takes more time and energy than just throwing it all ‘away’ in the trash. It is more expensive to buy an electric vehicle than a regular gas-guzzling automobile, and it is costly to install a solar photovoltaic energy system onto the roof of a house. Most urban centers are organized around easy flow of traffic and consumer goods, and it is the path of least resistance for most people.

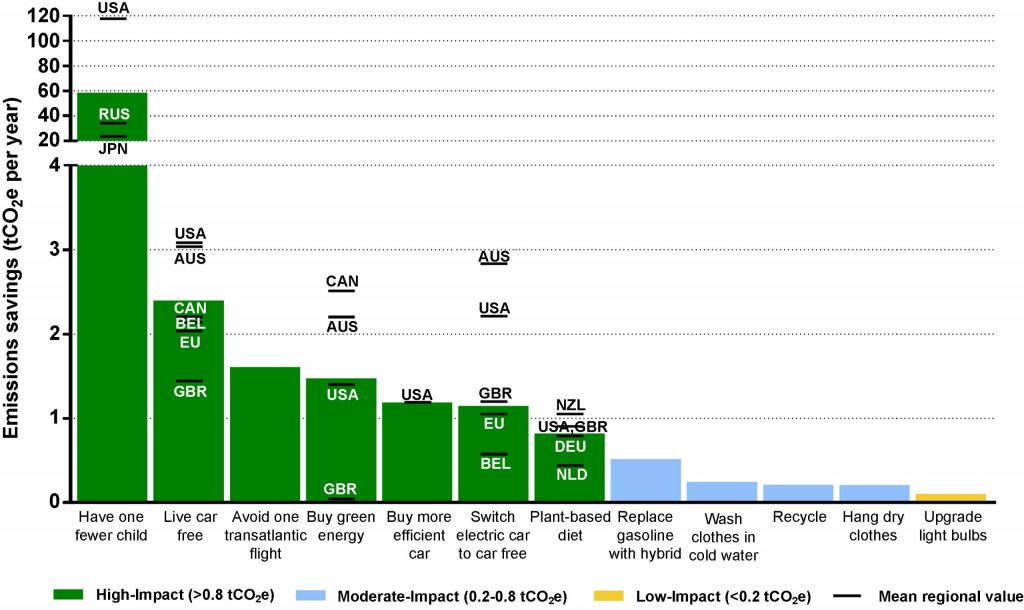

The infographic in Figure 9.5 depicts some other ways a person can reduce their own contribution to climate change.

According to Figure 9.2, the top three ways to reduce personal contributions to climate change are: (a) have one fewer child, (b) live car free and (c) avoid one transatlantic flight. Having children is a social and cultural norm in most countries across the globe, and in some places, choosing not to have children can be met with incredulity and disbelief, or worse, criticism. For many, having children and starting a family are major life goals that are equated to success and happiness. Culturally, this is the accepted norm in many countries across the world. The choice to not achieve these normative goals can be alienating and difficult. The second personal choice of living car free is just not feasible for many, especially in North America. Vehicles are the primary mode of transportation for people to get to work or to go on vacation. Cars have, for years, been a symbol of wealth. To many, a car represents freedom and accessibility. Finally, the third choice of avoiding a transatlantic (or equivalent) flight means forgoing a chance to see a loved one across seas, or a sun-drenched vacation after months of hard work. These are choices that are hard to make, and it is much easier for an individual to place greater weight to their immediate enjoyment and pleasure (effectively promoted by ubiquitous advertisements) over the long-term goal of mitigating climate change, an achievement that is not promised or secure, and the rewards of which may never be reaped personally. The change of moral norms is hindered by the fact that ‘carbon solutions’ are still widely perceived as belonging into the domain of ‘environmentalism’; the realisation that carbon mitigation will actually contribute to human security is not yet widespread. This extends even to UNHCR’s refusal to recognise ‘environmental refugees.’

Still, cultural and social norms may not always be the biggest barrier to a renewable energy transition. While these aforementioned barriers to change are real, there is still a strong environmental movement seen across the world advocating and pushing government and corporations for more action on climate change. The school strikes of 2019 and the ‘Extinction Rebellion’ movement impressively demonstrated that. Civil society has a part to play in influencing the market toward greater supply of renewable energy and sustainable products as well as pressuring governments to introduce regulations and legislation that will institute new, sustainable ways of living, and usher in new sociocultural systems. So why has change not occurred to the point where global emissions of GHGs are reduced?

Is the biggest barrier economic? Will the renewable energy transition simply cost too much for the global economic system to bear? The answer, gleaned from many economic and scientific studies, is simply no. On the contrary—it will save us enormous costs down the track (IRENA, 2019).

The renewable energy transition is fundamentally, at its core, a political struggle between current dominant systems of power and privilege and those advocating for new energy systems and a more secure future for all. To understand this conflation of energy and power, the following section will deconstruct the relationship between fossil fuels, money, and political power.

Politics, Money and Power

The world primarily runs on fossil fuels, and it has done so since the Industrial Revolution from approximately 1760. This energy revolution allowed massive leaps forward in technological, economic, and social development. Since then, total global fossil fuel consumption has increased exponentially (see Chapter 3).

During the early age of the Industrial Revolution through to the early 2000s, developed countries like the United Kingdom produced vast amounts of fossil fuel energy, a rate that has slowed in recent years (Tiseo, 2018). The United Kingdom has amassed the wealth and ability to invest in renewable energy technology, and reduce its fossil fuel production as well as its consumption. On the other hand, developing countries like China have seen an explosive increase in rate fossil fuel energy production and consumption. In all, production of all types of fossil fuel energy including coal, oil, and natural gas, has continued to increase globally (Ritchie & Roser, 2019).

The lack of political will is the primary reason why fossil fuel production and consumption have not slowed. While the IPCC, UNEP, and other major world organizations, have called on governments from around the world to limit and decrease fossil fuel production, to place sanctions or a moratorium on explorative drilling for fossil fuels, many countries, states, and cities, are still subsidizing and incentivizing the continued production of fossil fuels. Regimes for emissions trading are taking hold but their benefits accrue too slowly. The failure of governments to act manifests in many ways, including the distortion and obfuscation of evidence that climate change is caused by humans, and the continued subsidization of fossil fuel industries and outright refusal to invest in renewable energy technology.

The fossil fuel industry’s political ties are defined by the grassroots climate activism organization 350.org as a cultivation of “sponsorship relationships.”[13] Fossil fuels have a long history of close political ties to capital, not in the least because of its inherent physical power as an energy resource, and also because it is a source of immense profit and political power. Aside from the often bloody battle for rights to ownership and extraction (Auzanneau, 2018), many human rights violations and atrocities have been supported by partnerships with or directly funded by oil companies (Silverstein, 2014). Often, the extraction of fossil fuels in developing countries profits the company and corrupt politicians while leaving the nation’s citizens impoverished, and decimating the land and its ecosystems. The amassment of wealth in fossil fuel extraction and production over many decades has allowed some people to become very powerful. Jane Mayer documents clearly in her 2016 book “Dark Money,” the rise of the conservative Tea Party in the United States of America, with the systematic funding by billionaires with fortunes steeped in oil, coal, and gas. In this book, Mayer (2016) documents the funding of neoliberal, free market economic ideology in the political arena by billionaires like the Koch brothers and other oil magnates. These powerhouse businessmen have for years set up right wing think tanks, schools and non-profit foundations that either directly preach neoliberal thought or fund its dissemination. This co-option of education, media, and popular culture, makes its way into policy in the form of deregulation. This term is misleading because it does not mean a complete lack of government regulation, but rather it is a set of policies that protect the rights of big business and give free rein to corporations and businesses, leaving little protection for citizens. It is co-option of government by big business, big money, and big oil, to have social and political license to continue to profit from fossil fuel extraction and production. It proceeded in the shadow created by a massive and well-coordinated public relations campaign that obfuscated scientific findings about climate change and financed deceptive efforts to promote false ‘skepticism’, using the same tactics (and specialists) that were employed by the tobacco lobby before (Oreskes & Conway, 2010). A recent analysis indicated that climate ‘contrarians’ (i.e. deniers) enjoy a 49% higher media visibility compared to expert scientists (Petersen et al., 2019).