17.4: Case Examples Linking Social-ecological Insights with Human Security in Particular Bioregions

- Page ID

- 77204

Building on the examples above, we now turn to two specific examples at the meso-scale to grapple with the complexity of health security in particular social-ecological contexts. The meso-scale here refers to intermediate scales that tend to include unique micro-climates, watersheds or specific ecological biomes, but which may cross multiple human jurisdictions including local governance. Here, we utilize meso-level examples due to their inherent linkages between both the social and the ecological in manifesting health security risks.

Food Security in East Africa

Food security and human security are intimately related, with both having direct implications for health security (FAO, 2016). Some human security specialists have argued for “redefining food security in terms of securing vulnerable populations from the structural violence of hunger” (Shepherd, 2012, p. 28). Global food riots are a particularly strong exemplar of coupled social-ecological systems. As Berazneva and Lee state:

a sharp escalation in worldwide commodity prices precipitated the global food crisis of 2007–2008, affecting the majority of the world’s poor, causing protests in developing countries and presenting policymakers with the challenge of simultaneously addressing hunger, poverty, and political instability. (2013, p. 28)

Examining the inter-country variability in Africa, where a majority of the population are episodically food insecure, and about one quarter are chronically food insecure, they found that “higher levels of poverty (as proxied by the [country’s] Human Poverty Index), restricted access to and availability of food, urbanization, a coastal location, more oppressive regimes and stronger civil societies were associated with a higher likelihood of riots occurring” (p. 28).

Yet ongoing climate variability (environmental insecurity) and conflict (socio-political insecurity) also have effects on food prices, and hence food security. Raleigh and colleagues (2015) honed in on markets of the main trading town of first level administration districts in 24 African states with reported political violence January 1997 to April 2010. They found that “feedback exists between food price and political violence: higher food prices increase conflict within markets, and conflict increases food price. Lower than expected levels of rainfall directly increase food price and indirectly increase conflict through its impact on food price” (p. 188).

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) integrates complex analyses of food insecurity and malnutrition situations. Their website features a Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) network map of East Africa. An interactive zoomable versionof this map can also be accessed that shows regional food insecurity classifications in acute and chronic contexts.

These quantitative empirical findings are reflected in maps of ongoing acute food insecurity produced by the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS, 2019). Focusing in on East Africa, the update shows areas of both intense conflict and emergency levels of acute food insecurity (i.e. South Sudan), along with areas of ongoing crisis (e.g., Somalia), and those that are stressed (e.g. Kenya).

Particularly in such contexts, United Nations organizations have agreed to human security approaches to food security (FAO, 2016). In a narrative review on conflict and climate change, Brown and Crawford (2009) note that “reductions in crop yields and increasingly unpredictable weather patterns around the world may lead to higher prices for food and greater food insecurity” labelling climate “a ‘threat multiplier’ that makes existing concerns, such as water scarcity and food insecurity, more complex and intractable” (p. 2).

Huish (2008) has argued that “In the process of building common language between researchers and policy‐makers, the agreed definition of food security [has] excluded many important issues. As a result, the excluded, more radical issues have been pursued by off‐shoot movements that do less to directly engage the policy‐making process with existing policy‐making technocracy” (p. 1386). An example would be combined multinational corporation – government aid approaches which focus primarily on technology and markets, often not reaching the more vulnerable, African smallholder agricultural producers nor responding to their concerns (Rajaonarison, 2014).

The requirements for food security and environmental sustainability over the longer term have been set out globally (Cole et al., 2013). They include access to land, water, appropriate agricultural inputs, fair markets and supportive governance. Specific challenges and opportunities have been explored in East Africa in both urban (Yeudall et al., 2007 and more rural contexts (Braitstein et al., 2017), where the role of access to land, diverse agricultural production, promotion of dietary diversity, and human rights, including the right to food, have been given stronger emphasis. The latter are more consonant with some of the more radical approaches which Huish mentions, such as food sovereignty (Torrez, 2011) which explicitly frame the achievement of food security in social movement terms.

Cumulative Impacts of Multiple Resource Development Operations in Northern British Columbia

As indicated above, global land system change is significant, and largely occurring as a result of industrial agriculture and large-scale resource development projects. Resource development impacts human health through a variety of biophysical, but also social, ecological, cultural and economic pathways (Aalhus, 2017). This is a challenging conundrum for communities which are predominantly rural and remote, and rely almost exclusively on resource development pathways for local economic development (Bowles & Wilson, 2015; Halseth, 2015; Halseth & Markey, 2009).

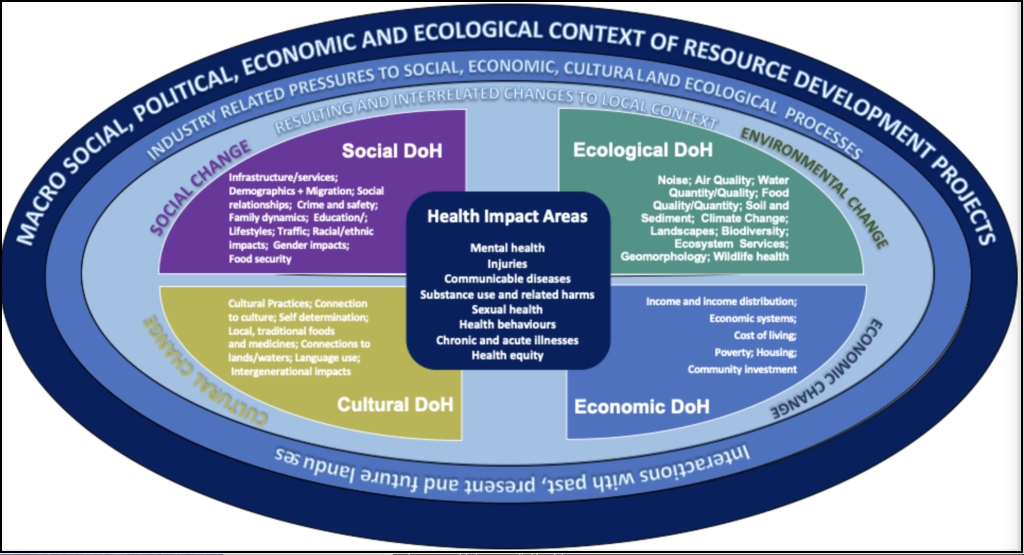

Figure 17.1 demonstrates how changing environmental conditions can produce reciprocal and interrelated changes across local contexts. These impacts to the determinants of health (DoH) thereby modify existing relationships between people and the land in ways that may create differential exposure to harm (i.e. living within close proximity to newly developed sour gas wells, or relying on an aquifer that risks contamination from multiple natural gas fracking operations) or modify risk factors in a local context (Buse et al., 2019). For example, the boom and bust dynamics of resource development can create large influxes of workers to a community without necessarily increasing services (Mactaggart et al., 2016; Shandro et al., 2011). This can lead to service-based stress, rising rates of substance use, homelessness and risks for women and children. During a bust, health services that were already functioning with limited capacity may see cuts that limits the ability of a community to address the social impacts left behind by resource development booms (Amnesty International, 2016; Buse et al., 2019).

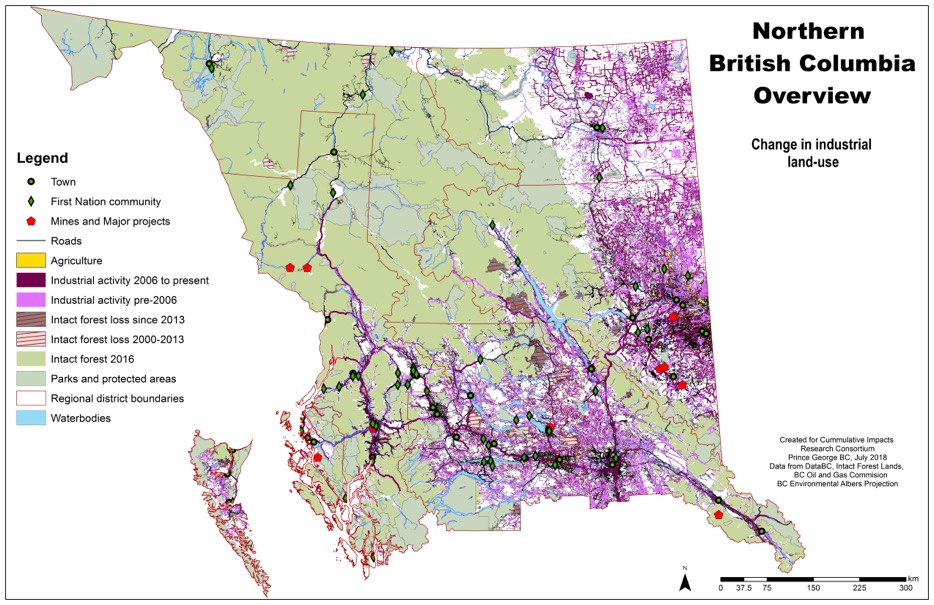

These issues become relevant to health security when and where local systems are unable to protect and promote human health. This is particularly salient in regions with multiple forms of resource development operating on the same land base which may produce cumulative environmental, community and health impacts (Gillingham et al., 2016). Cumulative impacts have been referred to as “death by a thousand cuts” or the “tyranny of small decisions” (Noble, 2010), and conceptualize how past, present and future development projects can interact with pre-existing land-uses in ways that create both positive and negative impacts for people, their health and the broader environments in which they are situated.

For example, Figure 17.2 illustrates an array of natural resource projects and supporting infrastructure developed across Northern British Columbia, Canada. Not only do each of the individual projects—whether a mine, hydroelectric facility, natural gas well or pipeline, and associated right of ways in the form of roads, railways and power lines—produce individual risks to human health, it is the confluence of multiple projects that poses new and emergent risks for health and the overall economic, political, social and health security of a population at a regional level, but particularly those regions that have a high dependency on natural resource operations as a principal economic driver, and where the land provides opportunities to exploit multiple types of natural resources.

Consider a simple example: the air quality and resulting respiratory health impacts of living adjacent to natural gas wells may put an individual at a certain degree of risk, living in a community that already had a smelter, pulp and paper mill, or a history of poor air quality can create new cumulative exposures for individuals and populations alike. However, these physical impacts can also be unpacked and understood in relation to other forms of cumulative impacts that have accumulated over decades and sometimes even centuries. For example, colonial impacts to Indigenous communities across the world are well-understood, and manifest in a variety of health impacts stemming from violence, trauma and a loss of culture (Greenwood et al., 2015). When combined with new environmental exposures from the earlier air quality example, a double injustice occurs, whereby determinants of health come into direct interaction with biophysical exposures producing new types of health impacts, challenges for health services delivery, or for the ability to access and benefit from ecosystem services that are inhibited by industrial change processes.

The two meso-scale case-examples presented here, offer multiple entry-points from which to explore both health security and SES. Related meso-scale case-examples have been found to be useful in a range of teaching and learning contexts that both directly and indirectly address issues relevant the interface of health security and SES, as exemplified the decade of work in the Canadian Community of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health (CoPEH-Canada) (see Cole et al., 2018; Parkes et al., 2017). Since 2016, CoPEH-Canada has run a multi-institutional hybrid course (Cole et al., 2018), and has consistently used the meso-scale of watersheds as a social-ecological systems context from which to explore course themes, connecting across institutional contexts in relation to themes of “The role of universities in progressing health within their watersheds” in 2016-2018 and “Health of humans and other species in their watersheds” in 2019. Both conceptual and field-based examples and experiences can be used to explore and appreciate the SES features of these meso-scales, and also to ‘zoom-in’ and ‘zoom-out’ to consider the benefits of examining related issues at multiple scales, including the use of ‘extension activities’ and exercises such as those presented below (see also Buse, Smith, et al., 2018; Galway et al., 2016; Parkes & Horwitz, 2016).