Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Causal modeling is the process of visualizing the relationships between concepts of interest (Youngblut 1994a, [b] 1994). Additionally, this process also encourages researchers to consider the possibility of other relationships between concepts that were not originally theorized or otherwise considered.

Causal modeling was popularized by Judea Pearl, among other scholars (Pearl 1995, 2009; Pearl, Glymour, and Jewell 2016). Underlying causal modeling is the concept of causality. In a public lecture at the University of California, Los Angeles, Dr. Pearl stated that “causality – namely, our awareness of what causes what in the world and why it matters” (Pearl 2009).

As a student of political science, it is important to know that the concept of causality has been broached with adherence or passivism in the discipline. Those who adhere to the concept of causality are vested in theorizing, hypothesizing, and accumulating empirical evidence that explains the causes and effects of political behavior, processes, and institutions. Research that does not aspire to declare and determine a cause-and-effect relationship is not rigorous, in the view of adherents. On the other hand, passivists of causality believe, while important, the discipline should not preclude or dismiss studies of politics that don’t have an explicit cause-andeffect relationship which is being examined. The aspiration is on discovery and explanation, not only cause-and-effect.

In his book Causality, Dr. Pearl (2009) shares: “The two fundamental questions of causality are: (1) What empirical evidence is required for legitimate inference of cause-effect relationships? (2) Given that we are willing to accept causal information about a phenomenon, what inferences can we draw from such information, and how? These questions have been without satisfactory answers in part because we have not had a clear semantics for causal claims and in part because we have not had effective mathematical tools for casting causal questions or deriving causal answers.”

Why are these questions important for political science students and scholars? Regarding the first question, we observe the world. From our observation, we begin the process of stating theories, producing hypotheses, and finding explanations from political actors, behaviors, processes, and institutions. The observed world offers us empirical evidence and this evidence is a prerequisite to inferring a cause-effect relation. With respect to the second question, political science grapples with what inferences can be drawn from information and how. Information includes quantitative and qualitative data. How we draw inferences from this information includes the use of probability, statistics, mathematics, and logic.

Causal modeling, as Dr. Pearl has explored, has an underlying logic and mathematics. For our purposes, we want to explore three visualizations to seed the utility of causal modeling and leave the underlying logic and mathematics for you to further explore on your own or in future courses. Below are three causal models: 1, 2, and 3.

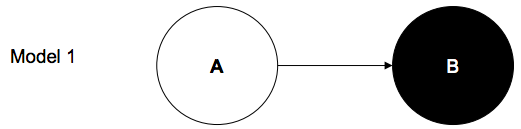

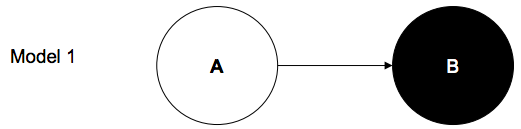

Model 1 shows the simplest relationship between two objects: A and B. There is an arrow that points from A to B, this denotes the direction of the relationship. One can assume when an arrow points from one object to another, that the pointing object is a “cause” while the pointed object is an “effect.”

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Causal model: A to B

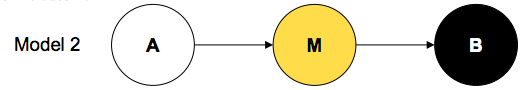

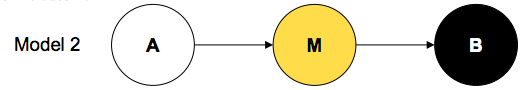

Model 2 shows the relationship between three objects: A, M, and B. There is an arrow that points from A to M. M stands for mediator, since it mediates, or stands in between, the relationship between A and B. Given that A influences B through M, A is more precisely stated as an “indirect cause”. While there is an arrow from M to B, M is not considered the “cause” because the model includes A.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Causal model: A to M to B

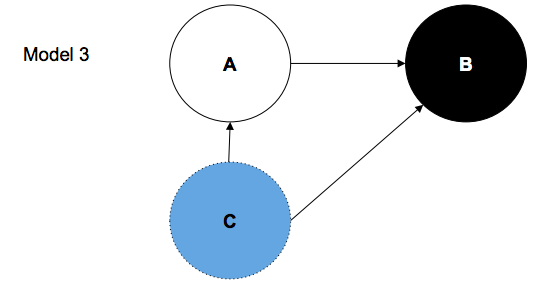

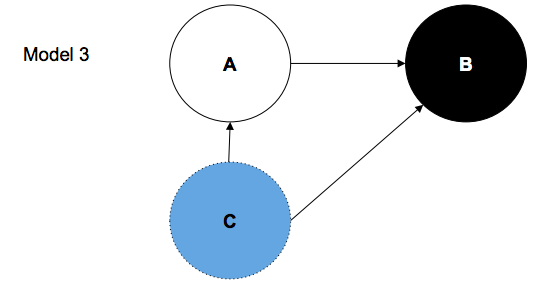

Finally, model 3 shows the relationship between three objects: A, B, and C. First, we notice that A points to B, meaning that A is considered a “cause” of the “effect” B. However, unlike model 2, we also see C. C has a directional relationship with both A and B. In this instance, C is called a “confounder” because we didn’t explicitly include it in the original model, as denoted by the dots instead of solid lines of the circle.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Causal model: C to A, A to B, and C to B

Drawing causal models is useful because it lets us “see” the relationships between objects of interest. As you explore political phenomenon, keep the tool of causal modeling handy.