2.4: Expanded Federal Government- The Stages of Federalism

- Page ID

- 129143

The relationship between the state and national government has not been stable. It has changed over history due to a variety of factors including the growth of the nation, the development of communications and transportations technologies, and ebbs and flows of the various political forces over time. Changes in constitutional interpretation also plays a significant role. The language in the U.S. Constitution is vague enough to allow for disputes over interpretation, as well as reinterpretation over time.

Scholars tend to divide the history of federalism into three eras: dual federalism (1789– 1933); cooperative federalism (1933–1981); and New Federalism (1981–present). The dates that mark the transitions from each era coincide with the elections of perhaps the two most transformative presidencies in the twentieth century: Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–1945) and Ronald Reagan (1981–1989).

Dual Federalism

The guiding principle of dual federalism was that the national and state governments are two separate spheres and should focus on their respective spheres only. James Madison, whose advocacy for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution included essays in The Federalist Papers, clarified their relative functions in Federalist 45:

The powers delegated to . . . the federal government . . . will be exercised principally on external objects, as war, peace, negotiation and foreign commerce. . . . The powers reserved to the several States will extend to all the objects which in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives and liberties, and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement and prosperity of the State.\(^{24}\)

The powers of the national government facilitated America’s rapid westward expansion. This entailed acquiring rights to the land from European powers, clearing it of native populations, and enticing people from the east to settle there by offering generous land grants. As local communities developed, and federal territories turned to states, governments were established that could allow these areas to rule themselves. Under dual federalism, these governments had sole authority in determining how best to care for their citizens. Often this was due to the simple fact that the national government had not yet developed the institutions that could do so.

Dual federalism was relatively easy to maintain during a period when interstate commerce was not common., transportation and communications were slow, and the institutions of the national government were just being built. This was changing however. Patents were granted for a variety of inventions making both transportation and communications easier. The Supreme Court was also making decisions which clarified the powers of the federal government. Prior to the Civil War this was the dominant concern regarding the federalism. Relevant cases include the Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824).

In Martin v Hunter’s Lessee (1816) the court decided a case involving land confiscated by the state of Virginia from a loyalist (a supporter of Britain during the revolutionary war) during the war. The confiscation was overturned in the Treaty of Paris, but Virginia refused to comply. The Supreme Court ultimately argued that the Supremacy Clause implied that the treaty took precedence over state law, and the land had to be returned.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) involved Maryland’s effort to drive the national government out of the banking business. Congress chartered a national bank in 1791, and re-charted it in 1816. Maryland responded in two ways, it imposed a tax on the bank and filed suit in federal court arguing that Congress lacked the authority to charter a bank since it was not expressly delegated in the U.S. Constitution. The Supreme Court held that the Necessary and Proper Clause did allow Congress to charter a bank, and the Supremacy Clause did not allow states to tax the national government.

In Gibbons v Ogden (1824) the court faced a case involving transportation over the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York. Both the state of New York and the United States claimed the right to regulate it. The Supreme Court ultimately agreed with the argument that the Commerce Clause gave the power to the national government.

Finally, a confrontation between the federal government and South Carolina led to the Nullification Crisis. The national government passed laws establishing tariffs in 1828 and 1832 on imported goods, sometimes by as much as sixty-two percent. Meant to protect struggling manufacturers in the North and farmers in the West against the competition of low-cost imports, the southern states bitterly opposed the law (which they called the Tariff of Abominations) for placing what they believed was an unfair burden on them. South Carolina’s John Calhoun developed the doctrine of state nullification—that states had the right to nullify (reject) federal laws within their boundaries—on the premise that the states created the national government, and as a result, each state has the power to determine the proper extent of national power. The courts ruled against this argument by invoking the Supremacy Clause, which holds that all governments in the United States should be in accordance with the U.S. Constitution and that the federal courts have the final authority to determine the meaning of the document. The crisis was ultimately averted through an agreement that the tariffs would gradually return to pre-1828 levels, but the crisis foreshadowed the Civil War. By declaring the right to nullify federal laws, southern states held state law above federal law, a premise that led them to secede from the Union to protect the institution of slavery.

After the Civil War, a similar decision was made in 1870 when a case involving Texas, and the legality of the laws its legislature passed when it was a member of the Confederacy, reached the court. The case was Texas v. White (1869) and it concerned the sale of Texas land by the Confederacy. The newly reconfigured Texas legislature, now once again as a member of the United States, claimed the sale was illegal and wanted the proceeds of the sale returned. The Supreme Court agreed declaring that the Union was perpetual, and the states had no power of secession. The Confederacy was never, legally, an independent nation.

Dual Federalism Fades

At the end of the Civil War, amendments were added to the constitution that laid the foundation for future expansions of national power. The most significant of these was the Fourteenth Amendment, which for the first time clarified the relationship between individuals and the national government. The Fourteenth Amendment held that if you were born in one of the states, whether you had been enslaved or not, you were a citizen of the United States. The Amendment overturned the Supreme Court’s ruling in 1854 that Dred Scott—as an enslaved African American—was not a citizen. \(^{25}\) The Fourteenth Amendment also includes the Equal Protection Clause, discussed earlier in the chapter. Much like the elastic clauses of the implied powers, the equal protection clause can be interpreted loosely, and after the Civil War, Black Codes evolved into Jim Crow laws that continued to allow states like Texas to discriminate against people based on race in such areas as education, employment, marriage, access to public accommodation, and transportation. The segregationist laws of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, as well as the White terrorism that included the Ku Klux Klan and lynching, would eventually bring federal intervention into how individuals were treated at the state and local levels, but under dual federalism policing was a sovereign obligation of the state.

During the same period, known as the Progressive Era, technology improved to the point where information began to flow instantaneously via telegraphs and telephones, and railroads made coast to coast travel available (Figure 2.4.4). It was easy not only for commerce to cross state borders, but crime as well. Problems related to health, safety, welfare, and morals were no longer just state and local. They crossed state lines, and impacted commerce. Consequently, state and local governments were not sufficient to address them. National laws were passed in a variety of areas which had previously been reserved mostly to the states, and the Commerce Clause increasingly became a constitutional justification for this reform legislation. Progressive Era reformers argued that as long as the activity involved interstate commerce, federal intervention was ok. Often these laws were challenged. Sometimes the Supreme Court found them constitutional, sometimes it did not, but in Texas reform of the railroad industry was a particular goal of farmers hurt by falling prices and the capricious price gauging of the railroads that took their goods to market.

Interstate Commerce Act of 1887

By the late nineteenth century, railroad corporations had attained a significant amount of wealth, and with it, political power across the nation. The power of railroad corporations in Texas led to separate articles in the 1876 Texas Constitution regulating both railroads and private corporations. The goal was to enhance competition in the industry, which undermined its profitability. But in 1886 the United States Supreme struck down state laws regulating railroads as violating the Commerce Clause, which then led to national government involvement.

White Slave Traffic Act of 1910

Throughout the nineteenth century cities across the United States struggled with prostitution, and other vices. Many cities allowed for its legality in designated areas, but the increase in urban populations, often driven by women moving in from rural areas led to concerns that participation in prostitution was not by choice. This coincided with a growth in organized crime that tied criminal activity in cities in one state, with those in another. This activity across state lines, along with its commercial nature—whether it was legal or not—led to the passage of national legislation addressing the transportation of women to travel across state lines for “prostitution or debauchery, or for any immoral purpose.”\(^{26}\) This term was loosely defined to refer to whatever law enforcement wished, and it led to expansion of a national law enforcement apparatus.

Keating–Owen Child Labor Act of 1916

The use of child labor in manufacturing and mining, among other areas, was becoming an increasing concern across the nation. State legislatures were finding it difficult to pass laws addressing child labor, however, due to the political power of multi-state corporations. The law prohibited interstate trade in the products of child labor. It was quickly found unconstitutional since the regulation of labor is not expressly granted to the national government and cannot be implied to it under the Commerce Clause.

These are only some of the laws passed in the decades of the Progressive Era. Other included the Pure Food and Drug Act, the Federal Reserve Act, the Income Tax Amendment, and the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote. Much of the expansion of national power, however, was piece by piece. There was no coordinated plan to change the overall orientation of the national government towards the states largely because there was no impetus to do so. The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing economic collapse would change that, however.

Cooperative Federalism

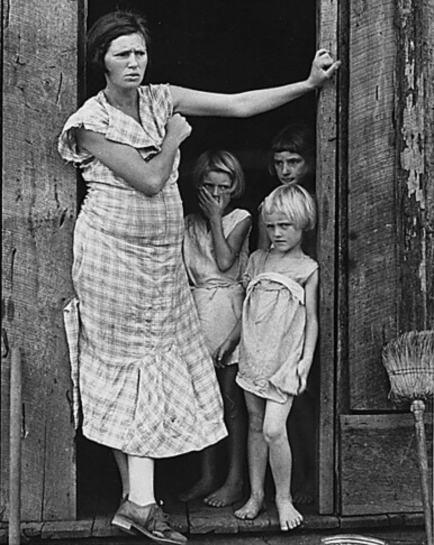

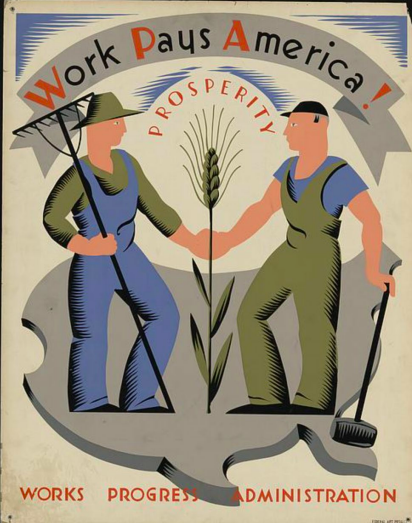

The Great Depression ushered in the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932. FDR’s predecessor, Herbert Hoover, adhered to dual federalism positions and refused to offer federal assistance to unemployed people, as that was a responsibility of state and local governments. His solutions involved traditional activities of the national government, such as raising tariffs, which had the opposite effect. At that time FDR was governor of New York, and began implementing programs to aid the unemployed, providing a blueprint of what he would do as president. The New Deal Roosevelt served as president from 1933 until his death in 1945, passing a series of laws, collectively known as the New Deal. These laws were a national response to the enormous pressures currently placed on the states alone, which were still fully in charge of the welfare of their citizens. Cooperative federalism emerged to address the widespread poverty across the nation (Figure 2.4.5). It involved works projects and efforts to prop up the price of farm products, as well as direct support to exhausted state and local government.

The economic crisis brought together a variety of factions that previously had not found much cause to work in common. Working under the label of the Democratic Party, the New Deal Coalition included the agrarians who advocated farm credit, farm cooperatives, and the redistribution of farmland to those who worked the land, primarily sharecroppers. The agrarians were the traditional base of the Democratic Party. It also included the social reformers of the Progressive movement, which the Party had lured to its side. The coalition would eventually include labor unions, and religious and ethnic minorities. The coalition also included Texas, as well as many prominent Texans, the most important of whom was Lyndon Baines Johnson. Johnson ran for Congress as a supporter of the New Deal in 1936 and expanded on its principles when he became president.

The severity of the economic crisis created a window of opportunity for an equally severe national response that included, in Roosevelt’s first 100 days, temporarily closing the banks, providing emergency relief measures like soup kitchens, stabilizing prices for agriculture, and creating work projects for the unemployed. The New Deal’s Tennessee Valley Authority allowed for the expansion of public ownership of a utility, providing the resources to build dams and hydroelectric power plants on the Tennessee River to expand access to electricity, including in rural areas. The Public Works Administration oversaw the construction of large scale infrastructure projects like bridges, dams, and hospitals (Figure 2.4.6). None were traditional responsibilities of the federal government, but state and local government resources had been exhausted.

Many projects were funded by the national government, but run by the state governments. The funding mechanism was the matching grant, which provided a significant amount of funds provided that a small amount was matched by the state in order to show that the state was invested in the program. The money was received with the understanding that it would be used for certain specific purposes as defined by the national government. These were called categorical grants.

Given the dramatic expansion of federal power made in these laws, successful challenges were made to many of the initial laws passed. The Supreme Court continued to be dominated by justices largely committed to dual federalism, and struck down laws that violated those principles. The national government attempted to justify these laws by arguing they involved interstate commerce, but a majority of justices on the Supreme Court initially disagreed. Two key laws were the National Industry Recovery Act (1933), which allowed the president to stimulate the economy by regulating fair wages and prices, and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (1933), which attempted to stabilize agricultural prices by purchasing surpluses in order to remove them from the market. These programs were challenged in court as unconstitutional and then altered and rewritten in light of court cases in order to be in compliance with the constitution.

The Social Security Act of 1935 created a variety of programs including unemployment insurance, aid to dependent children, and old age insurance, which is funded by a payroll tax. Before the Social Security Act, one-half of the elderly were estimated to live below the poverty line.\(^{27}\) Today, around ten percent of the elderly are estimated to be poor due to the benefits provided by Social Security. \(^{28}\) Upon signing the Social Security Act, Roosevelt described his hopes for what it might accomplish:

We can never insure one hundred percent of the population against one hundred percent of the hazards and vicissitudes of life, but we have tried to frame a law which will give some measure of protection to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-ridden old age.\(^{29}\)

This would become a model for a program establishing medical insurance for the elderly, also paid for by a payroll tax. The program was funded by both the eventual recipient and was matched by the recipients’ employer.

As was the case with the bulk of New Deal legislation, the Social Security Act was immediately challenged in court as having no constitutional authorization. As was not the case with previous legislation, it was found to be constitutionally justified use of the national governments power to tax for the general welfare. In addition to Social Security, FDR signed the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which granted employees the right to organize labor unions, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established a minimum wage and time and a half overtime pay for employees that work more than forty hours a week.

Roosevelt was succeed in the presidency by his vice-president Harry Truman. Increases, both proposed and real, in national power occurred during the presidency of Harry Truman, and the moderate Republican Dwight Eisenhower who succeeded Truman did nothing to roll back the legislation. Truman’s presidency transitioned towards a focus on racial issues, which were not on the agenda of Franklin Roosevelt out of a fear that it would break apart the New Deal Coalition by alienating the South. Truman went forward anyway, which did in fact alienate the South and the South began to slowly turn away from the Democratic Party.

Truman’s focus was on civil rights which included the desegregation of the military and proposals for civil rights bills, as authorized in the Fourteenth Amendment. He also revived discussions of expanded access to medical assistance, which would become a significant contribution to the evolution of federalism under President Lyndon Johnson in the mid-1960s when Johnson became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

The Great Society

A native of Texas, Johnson was elected on his own in a landslide in 1964. Having spent decades in Congress, first as a U.S. representative and later as a senator and senate majority leader. He put his legislative skills to work as president to pass additional legislation. Johnson’s Great Society programs intended to address chronic poverty and conditions that resulted from racial and gender discrimination, and would go further than had any previous programs. Great Society legislation promoted national objectives in states that were sometimes reluctant to support them. For example:

- Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation and made discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, or national origin illegal.

- The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which created Head Start, the Job Corp, and Upward Bound, to train young people so they could escape poverty.

- Social Security Act of 1965, which created Medicare, basic medical insurance for those sixty-five and older, and Medicaid, medical insurance for the poor.

- Voting Rights Act of 1965, which banned racial discrimination in voting.

- Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which distributed funds to schools in low-income areas.

- Higher Education Act of 1965, which created grants, loans, and other financial aid to help students acquire a college education. In 1964 fewer than ten percent of those over twenty-five earned a college degree.30 Today, the number is thirty percent.\(^{31}\)

Coercive Federalism

Many of these policies saw the national government inserting itself into local affairs, and sometimes pursuing objectives that were not supported by majorities at the state and local level. This was especially true in Texas, and it remains true at the state, even though many local governments welcome federal assistance in funding. A principal area of controversy was education, which was already a hot button issue following the decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that racial segregation in schools violated the Equal Protection Clause. This was compounded by the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed racial segregation in public accommodations, as well as the Voting Rights Act. While each passed, the opposition to them contributed to a counter-movement against cooperative federalism, which some derided as coercive federalism. The backlash was exploited by Richard Nixon, who used race as his so-called southern strategy to win the southern White vote. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina told his constituents, “If Nixon becomes president, he has promised that he won’t enforce either the Civil Rights or the Voting Rights Acts. Stick with him.”\(^{32}\) Nixon succeeded Johnson as president but had to resign from office amidst the Watergate Scandal. Georgia Democrat Jimmy Carter was then elected to bring integrity back to the presidency, and Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980 with a promise to roll back the expansion of national power.

New Federalism

Reagan’s stated purpose was to reduce the inefficiencies that exist in federal bureaucracies, in addition to allowing local areas to govern themselves according to their own wishes. What came to be known as New Federalism took a few different forms. One was devolution, which was the process of returning decision-making regarding policies to the state and local levels. The other was privatization, which challenged the idea that government agencies should implement the law. Private organization should be contracted out to do so instead. In Texas this has been done with highway construction, the management of prisons, and on the local level the provision of parking, as well as parking enforcement. A third was deregulation, which reduced the role that the national government played in the commercial and manufacturing process.

Reagan had already established himself as an opponent of national power as a spokesperson for the American Medical Association—where he campaigned against Medicare and Medicaid—and governor of California. Previous Republican presidents had selectively limited federal power in creative ways. One of the more commonly used ways of doing so was the block grant, which as opposed to the categorical grant placed limits on how federal funds were to be spent, would allow for their use to be broadened. The Community Development Block Grant program is still in operation today. The use of block grants allows for experimentation in the delivery of services, which is argued to be one of the principle benefits of the block grant. Along with devolution and privatization, it allows states and local governments to be “laboratories of democracy.”\(^{33}\) Policy successes can be copied; policy failures can be avoided.

While Reagan’s initial promise was to eliminate many federal programs—efforts that continue today—these were largely unsuccessful. But the effort, and a string of Republican victories in the presidency, largely put a halt to further encroachments on state power by the national government. The only significant exception is law enforcement and public safety. For example, in 1984 the National Minimum Drinking Age Act coerced states into raising their drinking ages to twenty-one by threatening to reduce their highway funding. The Violent Crime Control Act of 1994 also expanded the range of laws punishable by the federal government, enhanced their penalties, and required states to create registries for those determined to be sexual offenders.

The last requirement, among other requirements imposed upon states by the national government led to concerns about unfunded mandates, requirements that did not come with financial assistance by the national government. These include mandates regarding civil rights, education, and environmental programs, and have led to sporadic efforts to curtail them in laws such as the Unfunded Mandate Reform Act of 1995.

In the midterm elections of 1994, Republicans were able to flip both chambers of Congress. They controlled the House of Representative for the first time in forty years. This allowed for the goals of New Federalism to be achieved through the legislative process. Republicans ran collectively on a series of proposals they called the Contract with America. Cuts were proposed to child welfare programs and product liability penalties; procedures were designed to make federal budget increases difficult.

In the long run, these proposals did little to reduce the power of the national government. Opponents of cooperative federalism found more success rolling it back through the courts. Beginning in 1980, Republican presidents appointed more justices to the Supreme Court than Democrats. This allowed them to place justices on the court that were less likely than their predecessors to see a constitutional justification for the programs of the New Deal and Great Society. Among other things, they began narrowing the interpretations of the Commerce Clause that facilitated expanded national power. In the United States v. Lopez (1995) case, the Gun Free School Zones Act was overturned because the court did not agree with the argument that gun violence had an impact on commerce. Similarly, in 2000 the court did not agree with the argument in United States v. Morrison that the Commerce Clause justified the Violence Against Women Act, which allowed victims of assault to sue their attackers in federal court. So, while a state may pass such a law, the national government may not.

In 2013, the Supreme Court decision in Shelby v. Holder overturned parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Voting Rights Act required the federal government to check the implementation of election laws in states with a history of voter discrimination based on race or ethnicity. While the court argued that the federal government still had the ability to pre-clear (i.e., approve) such legislation prior implementation, in Shelby v. Holder it also ruled that the criteria used in 1965 to determine which states were subject to pre-clearance—mostly southern states—was no longer relevant. The Brennan Center for Justice noted that, “Within 24 hours of the ruling, Texas announced that it would implement a strict photo ID law.”\(^{34}\)

Though the trend towards state power has not been pervasive, exceptions have been made in certain areas. For example, in the case of Gonzalez v. Raich (2005), the court ruled that the federal Controlled Substances Act, which made marijuana illegal within the United States, overruled California’s Compassionate Use Act, which attempted to make the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes legal within the state of California. In this case, a majority of the justices ruled that the Commerce Clause authorized federal agents to confiscate marijuana that state law allowed under the argument that an interstate market in marijuana existed, which justified federal intervention in a purely intrastate matter. While the court ruled against California in this particular case, in 2009, the Department of Justice decided not to pursue such cases.\(^{35}\) Subsequently, seventeen states have legalized marijuana outright despite a prohibition at the federal level. Proponents of New Federalism use this as one of many examples of its benefits. It allows states to act as “laboratories of democracy,”\(^{36}\) and experiment with different policies, which can then diffuse across the nation if they seem worthwhile.

- James Madison, Federalist Paper No. 45 ("The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered"), 1788, https://guides.loc.gov/federalistpap...apper-25493409

- Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 (1857).

- White Slave Traffic Act (18 U. S. C. A. § 2421 et seq.), also known as the Mann Act, passed June 25, 1910.

- Benjamin W. Veghte, “Social Security’s Past, Present and Future,” National Academy of Social Insurance Aug. 13, 2015, https://www.nasi.org/discuss/2015/08...present-future.

- Veghte, “Social Security,”’ https://www.nasi.org/discuss/2015/08...present-future.

- Franklin Roosevelt, Statement on Signing the Social Security Act, FDR Library, Aug. 14, 1935, http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/odssast.html.

- Shawn Leavor, “How the Higher Education Act of 1965 Changed Education Today,” Sept 30, 2019, Defynance, https://defynance.com/how-the-higher...ucation-today/.

- Leavor, “Higher Education Act,” https://defynance.com/how-the-higher...ucation-today/.

- Strom Thurmond, quoted in Angie Maxwell, “What We Get Wrong about the Southern Strategy,” Washington Post, July 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlo...thernstrategy/.

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, Justice Louis Brandeis, dissent, 1932

- The Effects of Shelby County v. Holder, “Brennan Center for Justice, Aug. 6. 2018, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-wo...ounty-v-holder.

- Carrie Jonson, “U.S. Eases Stance on Medical Marijuana.” Washington Post, Oct. 20, 2009, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn...101903638.html.

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, Justice Louis Brandeis, dissent, 1932.