3.2: The Constitutions of Texas 1812–1876

- Page ID

- 129147

In addition to being a state within the United States, Texas has been governed by the constitutions of Spain as part of New Spain, Mexico as a Mexican state combined with Coahuila, the Republic of Texas as an independent nation when Texas won its independence from Mexico, and the Confederacy as one of the states that attempted to secede from the Union. Texas is the only state to actually spend a significant amount of time both as a state in a foreign nation and an independent republic, and one that had to be admitted to the Union twice. This makes the story that much more interesting as many of the features of these constitutions still exist in some form in the current constitution. These constitutions divide well into three sections, with three constitutions in each.

The first section includes constitutions by the Spanish or Mexican governments for the Texas territory, the Coahuila and Texas state constitution that Texas delegates helped write as part of the United States of Mexico, and the constitutional crisis that led to Texas’s Declaration of Independence in 1836.

The second section includes constitutions written by political elites in Texas, first for an independent nation, second for a state within the United States of America, and third for a state within the Confederate States of America.

The final section includes the three constitutions that followed in rapid order after the defeat of the Confederacy. The question was what type of constitutional design would be acceptable to both the national government and the people of the state. Three versions were necessary before one was found acceptable to both.

Spanish Law: The Constitutions of 1812, 1824, and 1827

The Spanish Empire began in 1521 with the fall of Tenochtitlan, which is the historic center of Mexico City today. Spain claimed the bulk of North America among its possessions. In fact, it was only able to govern the part south of what is now called the Rio Grande. Its only real incursion northward occurred in response to evidence that France had briefly established a presence in what is now Victoria in East Texas. The need to settle the area that became Texas was in part to provide security. Hostile tribes controlled the plains, primarily the Comanche, and settlement north of the Rio Grande created a protective barrier for the area to the south.

While Spain made exploratory visits to the eastern Atlantic Coast and established a small number of settlements there, the lack of ready mineral resources—such as the significant amount of gold and silver available in Mexico and South America—made the endeavor pointless. As the United States began surveying extensively, and making sophisticated maps, it became easier to determine which nation controlled which land. Some disputes still existed. For example, when Thomas Jefferson authorized the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France—territory that they had just acquired from Spain—he was under the impression that the land extended to the Rocky Mountains and would have included Texas. The signing of the Adams–Oniz Treaty in 1819 set the Sabine River as the eastern border of the Spanish Territory, and Spain ceded Florida to the United States in return.

What follows is a series of events that lured American settlers, rapidly marching westward with little interest in the legality of settlement, to Texas. Other events involved disputes between Spain and Mexico, leading to rebellion and the establishment of the nation of Mexico. Still others were complicated by questions regarding the type of constitutional system that would govern an independent Mexico and the type of relationship that would exist between its central government and its states. In each case, the number of Anglo American settlers increased and as their population grew they began chafing under a constitutional and governing system they were unable to influence.

The 1812 Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy Prior to the Spanish Constitution of 1812, all of New Spain, including the missions and local settlements north of the Rio Grande, operated loosely under the Catholic Church, the military, and Castilian (Spanish) law. Aspects of Castilian law were retained by Texas in later constitutions. These included simple civil trial procedures, common ownership of marital property between husband and wife, and homestead protections. Many of these remain in Article 16 of the current version of the Texas Constitution:. Section 49 provides homestead protection:

The Legislature shall have power, and it shall be its duty, to protect by law from forced sale a certain portion of the personal property of all heads of families, and also of unmarried adults, male and female.3

Section 52 goes on to stipulate common ownership:

On the death of the husband or wife, or both, the homestead shall . . . not be partitioned among the heirs of the deceased during the lifetime of the surviving husband or wife, or so long as the survivor may elect to use or occupy the same as a homestead, or so long as the guardian of the minor children of the deceased may be permitted, under the order of the proper court having the jurisdiction, to use and occupy the same.4

Constitutional rule came to the area that would become Texas in 1812 during the Napoleonic Wars when Napoleon deposed the Spanish King Ferdinand VII and established a constitutional monarchy with a legislature and his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne. This marks the switch from the absolute monarchy that had existed before. The key feature of the constitution was that limits were placed on the power of the king, certain rights established for the people, and a representative system—a republic—created. Many components are familiar, including separated powers, a legislature, freedom of the press, and a complex indirect electoral system. Others would not be, including Catholicism as the official religion and universal adult male suffrage. When Ferdinand VII regained power in 1814, he dissolved the constitution, the legislature, and the very idea of representative democracy, but he was forced to reconsider in 1820 and reinstate the constitutional monarchy to avert a military coup.

With Spain in turmoil in Europe, a war for independence broke out in Spanish Mexico. It would last from 1810 to 1821. Royalist forces supporting Spain battled republican forces supporting an independent Mexico and the elimination of a monarchy. Spain had initially

restricted settlement in the Tejas region to Spanish citizens, but few were interested. So Spain granted a land speculator named Moses Austin land grants for immigrants—most of them Anglo Americans from the southern United States. Land speculation and emigration were lucrative endeavors at the time.

Why did people come to Texas? Like much of the land west of the Mississippi River, Texas was fertile, open territory. Davy Crockett, an early transplant from Tennessee, would call Texas, “the garden spot of the world.”5 Others were less kind in remarking on “floods, mosquitos, and violent encounters with Indians.”6 Many saw economic opportunity in developing commercial centers, which provided the basis for the cities which now dominate the state. Recent research has thrown a curve at our understanding of how cities like Houston were actually founded. It has been long held that the city was founded by the Allen Brothers, John and Augustus. Recently it has been maintained that Augustus’s wife Charlotte was the impetus behind the project.7 Her father was a developer from upstate New York, who gave Charlotte the money that may have purchased the land. As women could not sign contracts. Her plans had to be legalized by her husband’s signature.8 As an incentive for immigration, once people settled in Texas, U.S. debts could not be collected. Moses’s daughter Emily Austin Byran warned her brother Stephen about creditors outside of Texas in a letter, “I am fearfull that if you got to N. Orleans, you will meat [sic] with some unpleasant things. I have reference to one or two Notes of yours that are in the hands of some ill-natured persons, and I have been inform’d that one of them has been forward’d to New Orleans for collection.”9 So, Anglo American settlers arrived looking for cheap land and a fresh start. Those who came to Texas also understood they would have to comply with the requirements of the Spanish Constitution, including an acceptance of a state religion—Catholicism—and limits on enslavement. Enforcement of these requirements was lax, however. Spain, and later Mexico, needed the settlers to help develop resources, increase agriculture and commerce, and provide a buffer against the Plains Indians. Moses Austin’s death, coupled with the end of Spanish rule and the creation of a new constitutional order, would delay the arrival of the new settlers. Even without the land grants, approximately 2,500 Anglo American settlers were in the province, many illegally.

The 1824 Mexican Constitution Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, but the early years of Mexican independence were chaotic, and the government in Mexico City moved from monarchy to republic to dictatorship, with numerous coups in between. From 1821 to 1823, Mexico—including Texas—was a constitutional monarchy under Augustin de Iturbide, Emperor of Mexico, who designed the white, green, and red of the Mexican flag to represent “religion, independence, and unity,” more specifically the dominance of the Catholic Church (white), the political independence of Mexico (green), and the social equality of all inhabitants of Mexico with no distinction made between Europeans, Africans, Asians, or Indians (red).10

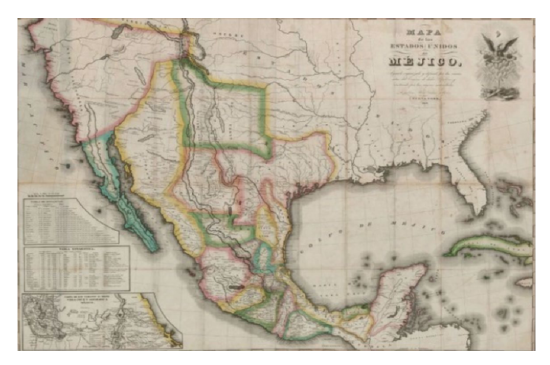

State governments in Mexico grew in strength at this time and began electing their own legislatures. Slowly a federal republic emerged. When the states and provinces sent delegates to write the 1824 Constitution they did so with instructions by their respective legislatures to create a federal republic, with sovereignty based in the states. Juan Jose Maria Erasmo Sequin represented Texas in the assembly, which established nineteen states, as well as four territories, and allowed the states to create their own constitutions (Map 3.1). At least at the beginning, power was vested primarily in the legislature, and the states had a degree of autonomy.

Map 3.1 Map of the United States of Mexico, 1828. SOURCE: Texas General Land Office

Mexico opened its borders to immigration under the General Colonization Law that enabled all heads of household regardless of race, religion, or immigrant status to acquire land in Mexico. Between 1824 and 1828, Moses Austin’s grant—taken over by his son Stephen and reauthorized under Mexico—had almost 300 land titles between the Brazos and Colorado Rivers. The settlers he selected were educated and propertied, and fourteen were slave owners, bringing with them the institution of slavery to Texas. Many were Protestants, who did not wish to convert to Catholicism and who were committed to personal liberty and private property (property in the sense of the early settlers included people who were enslaved). These were the core of those who would seek to govern themselves under their own constitution. But before that occurred, they spent time being governed under the 1827 Constitution of Coahuila y Tejas.

The 1827 Coahuila y Tejas Constitution The 1824 Mexican Constitution—as originally written—emphasized the importance and autonomy of state governments and established the state of Coahuila y Tejas. Each state was allowed to then craft its own constitutions. As a border state, it had a military under a single commandant general. The state was also divided into departments, and the departments were subdivided into municipalities, which contained mayors and city councils. Coahuila was among the poorest provinces in Mexico, and like Texas, sparsely populated.

All of Texas was originally only in the Department of Bexar, and then further subdivided into Bexar, Brazos, and Nacogdoches. While this gave them three representatives, the majority were from Coahuila, and the capital—Saltillo—was there as well. This meant that the Anglo Texans were a minority within the state and had to travel a long distance for government business. Anglo American immigrants, especially those who arrived in the years following the drafting of the Constitution of 1824, also resented that all political matters were handled in Spanish. The abolition of slavery in 1829 by Mexican president Vicente Guerrero—of mixed Indian and African descent—would have been a clear shot at Anglo immigrants in Texas, but Stephen F. Austin was able to procure an exemption for slavery in Mexican Texas at the time.

Over the course of the next twelve years, the nature of the Mexican government would change. Forces existed that continued to support a centralized monarchy, mostly the elites, while others wanted a federal republican system similar to that in the United States. The growing Anglo population led to passage of the Law of April 6, 1830, which placed limits on Anglo immigration—partially leading to the complaints contained in the Texas Declaration of Independence written in 1836. This, coupled with recently elected President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s efforts in 1835 to reduce the powers of the states, led to a constitutional crisis, a war for independence, and a new constitution as an independent nation

Constitutional Crisis The upheavals in Mexico led the Texans to call Conventions in both 1832 and 1833 to discuss options. A decision was made to officially request that Texas be allowed to be an independent state within Mexico. In 1833 they drafted a constitution to be proposed to the Mexican government. Tejanos—Spanish, Mexican, and indigenous descendants in Texas— opposed the Conventions, as well as the resulting document.

The key goal of the new constitution was to separate from Coahuila. The document was relatively short; its content a reflection of the values and traditions of the Anglo Americans from the South who had been recruited to the state. Many of its features reappear in most, and in some cases all, of the constitutions to come. These included the due process rights common in the American states (for example, protection against unlawful search and seizure and the right to be tried by a jury of your peers), the separation of powers backed up with checks and balances, and a wide variety of elected positions with short terms and term limits. All of these are meaningful ways of limiting government powers. Other parts that would be retained in the future included the provision of a free public education.

One components of the document proved ominous. Article 2 in the section on General Provisions claims the right of rebellion:

Government being instituted for the protection and common benefit of all persons, the slavish doctrine of non-resistance against arbitrary power and oppression is discarded, as destructive of the happiness of mankind, and as insulting to the rights, and subversive of the liberties of any people.11

Stephen F. Austin was selected to deliver the constitution to the Mexican government in Mexico City, but upon arrival was “incarcerated in a dungeon, for a long time [February 22 until December 1834] , one of our citizens, for no other cause but a zealous endeavor to procure the acceptance of our constitution, and the establishment of a state government.”12 This was an indication that the right to petition for grievances, as well as habeas corpus (which protects against unlawful detention), was not acknowledged and Austin’s imprisonment became a key grievance in the Declaration of Independence in 1826.

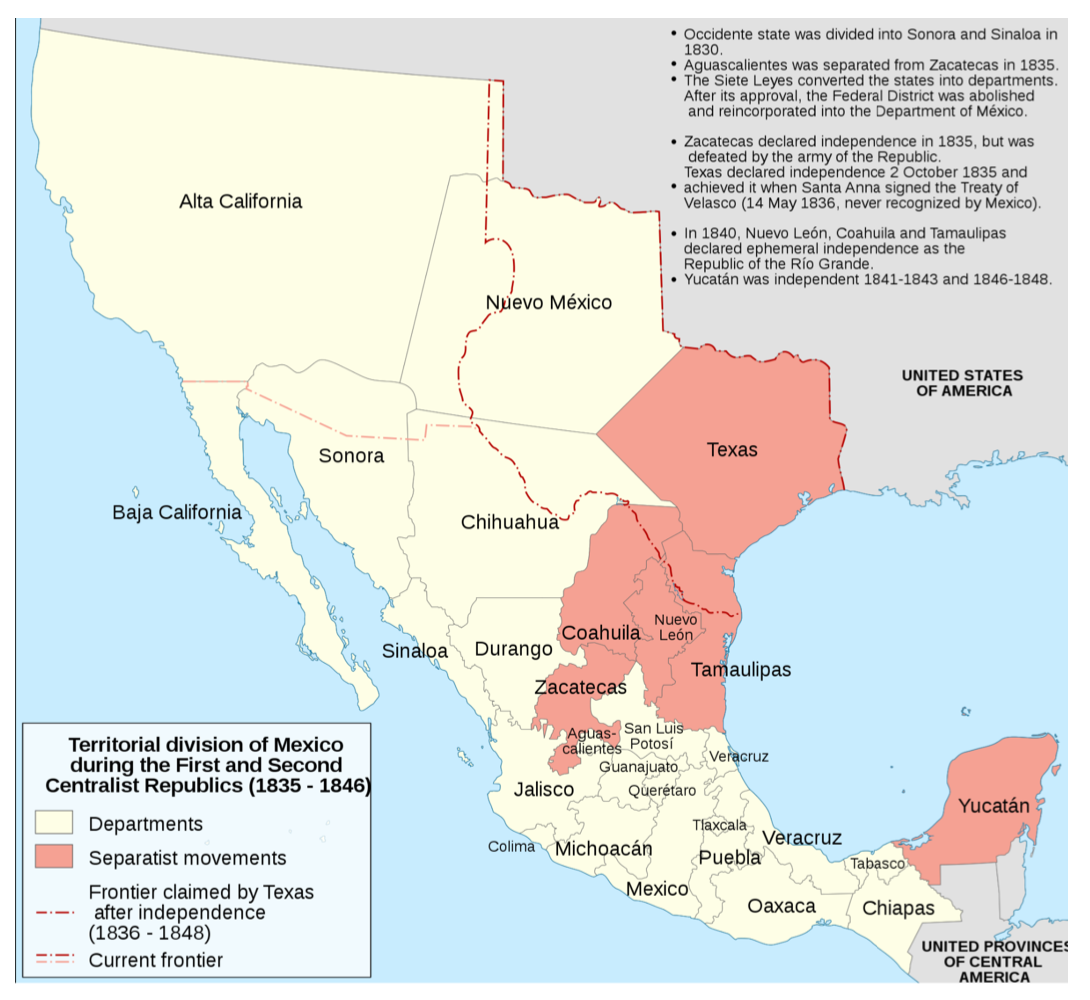

In 1835, President Santa Anna, on his own authority, revoked the 1824 Constitution to grant himself additional power. Santa Anna dismantled state legislatures to make the states fully subject to national power. This was the final impetus to independence, not just in Texas but in the Mexican states of Yucatan, Tabasco, and the Republic of the Rio Grande (Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, Coahuila), among others. Each declared sovereignty and initiated their own independence movements (Map 3.2).

Map 3.2 A map of Mexico, 1835–1846. The red areas show regions where separatist movements were active.

Texas then passed a Declaration of Independence on November 11, 1835, to take arms up against Mexico, create a provisional government, and produce, in the midst of the Texas Revolutionary War, not only another constitution but also a Declaration of Independence stating the reasons for independence.

The Texas Declaration of Independence of 1836 As with the Declaration of Independence of the United States, the Texas Declaration of Independence of 1836 justifies their decision to rebel. Its authors—the same group of people who would also write the 1836 Constitution of the nation of Texas—argued that Mexico had violated basic governing responsibilities, in addition to violating promises made to the Anglo Americans who were “invited and induced” to migrate to Coahuila and Texas.13

The central complaint made by the Anglo Texans was that Mexico was no longer a federal republic composed of states. It was in the process of being transformed into a centralized unitary system (discussed in chapter 2) under the control of Santa Anna and backed by the “combined despotism of the sword and the priesthood.”14 In a unitary system the president appoints all other top executive officials. Other complaints included:

- the refusal to consider Texas’s request to be made an independent state within Mexico;

- the “incarceration in a dungeon, for a long time”15 of Stephen F. Austin who delivered the request;

- the lack of trials by jury;

- the failure to establish “any public system of education . . . although it is an axiom in political science that unless a people are educated and enlightened, it is idle to expect the continuance of civil liberty, or the capacity for self-government”16;

- the need to travel a long distance to Saltillo, which was the capitol of the state of Coahuila and Texas, for representation;

- the need to learn Spanish in order to participate in the legislative process.

Being a minority in the state also meant that they were unable to pass laws that secured their interests. Additional issues included the right to possess guns, the preservation of worshipping according to their own conscience, and a refusal to provide security against native tribes. These would form the nucleus of the rights and procedures, based on what they were accustomed to in the United States, in subsequent constitutions.

Independence and Statehood: The Constitutions of 1836, 1845, and 1861

The principle constitutional question during this period was whether Texas would be governed under a national constitution for the Republic of Texas or a state constitution under either the United States of America or the Confederate States of America. Three wars would help answer those questions. The Texas War of Independence in 1836, which created the nation of Texas, the 1845 Mexican-American War, which led the Mexico’s recognition of Texas, and the Civil War. The transitions that accompanies each war led to changes in the state’s constitution, but the principle change during this period was that the constitutions would be written by Texans, primarily Anglo Americans influenced by the frontier values of westward expansion and the southern values of an economy based on the labor of enslaved people of color.

Suspicious of centralized power, the framers preferred that power be as localized as possible, and even then, tight controls were imposed on office holders. This was best expressed in making as many government positions elective as possible, splitting governing institutions into multiple offices, making terms as short as possible, placing limits on how many terms could be served, and setting salaries and other benefits low. In addition, central services such as education and law enforcement were to be implemented locally, and overall limits placed on how much revenue (taxes) could be collected by the government, as well as the potential size of state budgets. Efforts were also made to use the legal system to rollback expansions of national power by arguing they are violations of the United States Constitution and the right of states to govern themselves. Texas was heavily influenced by such principles as these that emerged in the nineteenth century under the banner of Jacksonian democracy, so named for President Andrew Jackson who formed the Democratic Party in 1828 and advocated for common Americans to have more influence on political institutions and especially for the expansion of suffrage to all White men, not just the elite who owned property.

In addition, the philosophical perspective of the framers was based on the practical realities of frontier justice. The size and emptiness of the state—and the presence of tribes such as the Comanche—made the implementation of the law, and the administration of justice, difficult and costly. Individuals took matters into their own hands, and a legal system allowed for it. The original 1876 Constitution would codify this into language in Section 4 of Article 16: (General Provisions) prohibiting those who had participated in duels from voting or holding office, and in Section 20 of the Bill of Rights, prohibiting the practice of “outlawry,” stating “no citizen shall be outlawed.”17 This removed certain people from being protected by law, meaning effectively that anyone could punish them. Ongoing examples include the explicit allowance of keeping and bearing arms for the purpose of self-defense.

The authors of the 1836 Constitution, and all subsequent ones as well, were familiar with the structure of the United States Constitution and mimicked it. The structure is different from that of the Spanish and Mexican Constitutions. The structure begins with a Preamble followed by a Bill of Rights, which lays out basic liberties and political rights, much of which is similar— often word for word—with those in the national document. All Texas constitutions also include a statement regarding the separated powers, and declaring that each institution is limited to its specific functions and is not to interfere with those of the others unless stipulated in the constitution. This is followed with three separate sections detailing the design of the institutions vested with the three separated powers: the legislative, executive, and judicial. The 1836 Constitution contains a large section titled General Provisions, which includes items that would later become separate sections in subsequent constitutions: suffrage, education, taxation, counties, and others (Table 3.1).

| 1836 | 1845 | 1861 |

| Preamble | Preamble | Preamble |

| Article 1 - Powers | Article 1 - Bill of Rights | Article 1 - Bill of Rights |

| Article 2 - Legislative | Article 2 - Powers | Article 2 - Powers |

| Article 3 - Executive | Article 3 - Legislative | Article 3 - Legislative |

| Article 4 - judicial | Article 4 - Executive | Article 4 - Executive |

| Article 5 - Oaths | Article 5 - Judicial | Article 5 - Judicial |

| Article 6 - President & VP | Article 6 - Militia | Article 6 - Militia |

| Schedule | Article 7 - General | Article 7 - General |

| General Provisions | Provisions | Provisions |

| Declaration of Rights | Article 8 - Slaves | Article 8 - Slaves |

| Article 9 - Impeachment | Article 9 - Impeachment | |

| Article 10 - Education | Article 10 - Education | |

| Article 11 - Head-Rights | Article 11 - Head-Rights | |

| Article 12 - Land Office | Article 12 - Land Office | |

| Article 13 - Schedule | Article 13 - Schedule |

Table 3.1 Outlines of Texas Constitutions, 1836-1861

The 1836 Constitution The Convention of 1836 wrote both the 1836 Constitution and the Texas Declaration of Independence in early March while the Battle of the Alamo was raging in San Antonio, and one month prior to the defeat of Santa Anna’s forces in San Jacinto. It was attended by elected delegates who tended to be young recent arrivals to the state supportive of independence. Large sections of the document were lifted from the United States Constitution. The opening Articles outline the separated powers, and the basic design of each governing institution. In many ways, this remains the basic design of these institutions in all subsequent constitutions. The terms were short—one year for the House, three years for the Senate, three years for the president, and four years for judges. The executive branch of the1836 Constitution is different from the current design in two ways: (1) it is unitary—meaning that the president appoints all other top executive officials, and (2) presidents are not eligible for re-election, though they can run again after sitting out one term. In addition, the 1836 Constitution adopted "the common law of England," for criminal cases, which included trial by a jury of peers, though Spanish law remained in effect where it was practical, or, as stated in the 1836 Constitution, the common law will be introduced “with such modifications as our circumstances, in their judgment, may require.”18 The common law of England is the body of law that traces its roots to judges and the customs of the people in the history of England.

Under Mexican rule, Texas was unable to limit citizenship, nor was it able to ensure that slavery would be protected since Mexican law did not allow it. Both were addressed in the General Provisions of the Texas Constitution. Section 6 limits citizenship to “free white persons” that have resided in the state at least six month, made an oath that they intended to live in Texas permanently, swore support to the Constitution, and swore allegiance to the Republic of Texas.20 Section 9 stated that “persons of color” who were already enslaved were to remain so.21 Emigrants to the state were permitted to bring enslaved people with them, and “no free person of African descent, either whole or in part”22 was able to live permanently in the state, unless otherwise authorized by the Congress. Section 10 held that those who resided in Texas prior to the day the Declaration of Independence was signed, were to be considered citizens—except for “Africans, the descendants of Africans, and Indians.”23 The right of citizenship carried with it entitlement to land. Head-Rights (land-ownership) and the Land Office are separate Articles in subsequent constitutions.

The document concludes with a Declaration of Rights, which contained seventeen provisions that form the basis of the Texas Bill of Rights contained in future constitutions.

The 1845 Constitution The years following nationhood were as tumultuous as those preceding it. Security continued to be a major problem. Mexico did not recognize the independence of Texas following 1836. Hostilities along the border, including a temporary seizure of San Antonio in March 1842 by the Mexican Army, flared occasionally and were reminders that Mexico intended to seize Texas for itself when possible. Settlers who had hoped for an early commitment of support from the United States were disappointed due to U.S. reservations regarding how doing so would impact relations with Mexico. In addition, opposition to Texas’s statehood continued out of an unwillingness to add another slave state to the Union. Some have suggested that the debate regarding whether new territories and/or states would be free or slave exacerbated the march towards civil war.

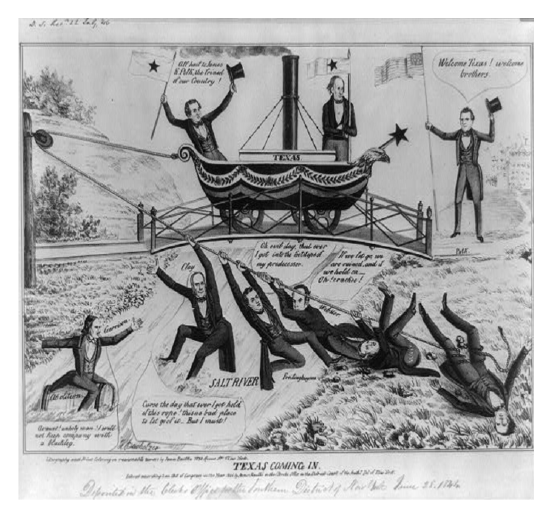

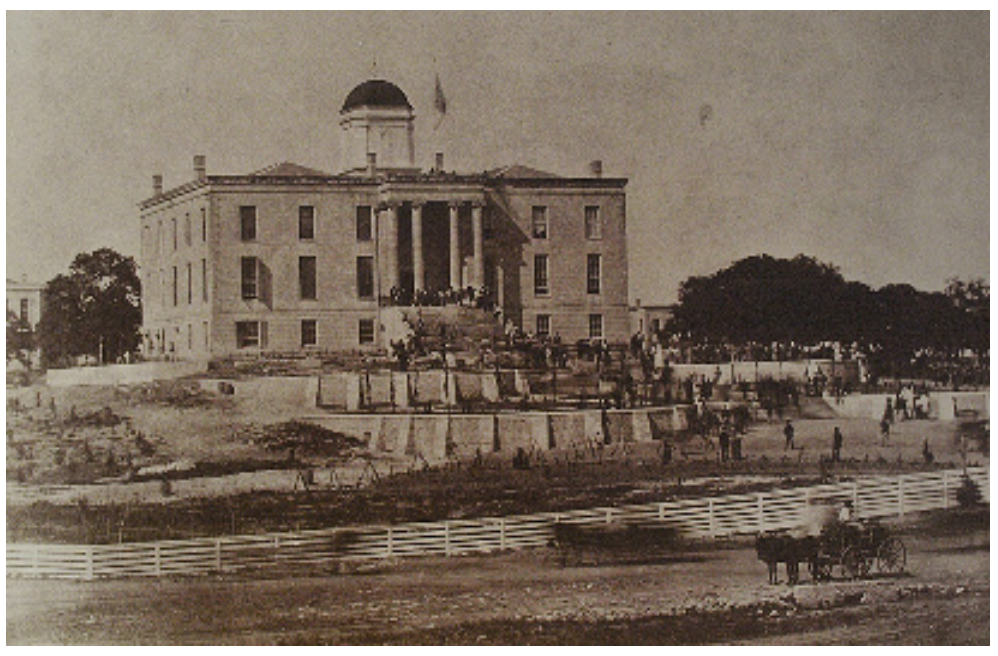

Calls for continued westward expansion drowned out these concerns, however. James Polk won the presidency in 1844 on a platform that included annexing Texas. Polk’s victory led to a resolution being quickly introduced in Congress stating their acceptance of the new state “with a republican government adopted by the people of said republic.”24 A joint resolution of the United States Congress extended an annexation offer to the state. This led to a Convention during the summer of 1845 to consider both the proposal and to write the Constitution of 1845 for the state of Texas. The Convention overwhelmingly accepted the offer of statehood, fifty five to one (Figure 3.2).

As with the 1836 Convention, the bulk of participants were from southern states. Both annexation and the new constitution were accepted by Texas voters on October 13, setting the stage for both to take effect December 19, 1845. It was significant that both were done at the same time. Law established under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 created a system where acceptance into the U.S. allowed the U.S. to take ownership of the land. If Texas had been a federal territory when it was annexed, it would have lost ownership of its public lands. By entering as a state, it retained possession of them and all the revenue likely to be drawn from their use. Texas was also allowed to split into up to five states if Texas voters approved; something that did not happen.

The new constitution was modified since it was a state rather than a national constitution, removing language related to the needs of a nation—such as citizenship requirements and laws related to international relations. It expanded the General Provisions of the 1836 Constitution into separate Articles on the militia, enslaved people, impeachment, education, head-rights, and the land office.

Article 3 on the Legislative Department begins with two section (Section 2 and 29) clarifying who was qualified to vote in the state. In each case it was made clear that “Africans, the descendants of Africans, and Indians” were ineligible.25 Section 29 of the Article also authorizes a census—which determined the outlines of House and Senate districts.

The design of the legislature mirrored that of the current legislature, bicameral with two and four year overlapping terms for the House and Senate, respectively. The House could not consist of less than forty-five, or more than ninety, members. The Senate could not be less than nineteen, or more than thirty-three, members. They were to be paid three dollars a day when in session, and three dollars for every twenty-five miles they travelled to the capital.

In 1845, the state began to experiment with the plural executive mentioned earlier in the chapter. The Texas executive branch is unlike the national system (where the executive power rests with the president). Instead power is shared, and in 1845 the power was shared between the governor and lieutenant governor—each elected separately for two year terms. They could not serve more than four out of any six years. The legislature was responsible for selecting the state treasurer and comptroller of public accounts, each served two year terms. The design of the judiciary was very simple created with language borrowed from the U.S. Constitution. It created a Supreme Court, and inferior court as created by the legislature. Judges were nominated by the governor with the consent of the Senate for six years terms, which gave the judiciary independence from the voters.

Article 6 concerned the militia—which is not the subject of any Article of the current constitution. It is brief and contains only four sections. A militia could be created, the governor could call it forth, people were allowed to opt out of service—invoking conscientious scruples— though they had to pay. Licensed ministers did not have to serve and could not be required to work on roads or serve on juries.

Article 8 covered slavery. This was the first time slavery was directly addressed in the constitution. It contained three sections. The first forbad the legislature from emancipating those who were enslaved without the consent of their owners and without paying their owners for the loss of property. It also mandated that slaves be treated humanely. The second guaranteed an impartial jury for enslaved people tried for crimes “of a higher grade than petit larceny.”26 And the third stated that certain crimes against enslaved persons were to be punished as they would be against a White victim, “except in case of insurrection by such slave.”27

Articles 10, 11, and 12 dealt with education, land ownership, and the management of public lands. Free schools were to be established and a perpetual fund was to be created, with revenue collected from the use of public land. A process was created for determining who owned specific parcels of land. Head-rights, and later land titles, would be a subject in successive constitutions until they were judged to be unnecessary in 1969 with outstanding land claims settled by then.

Ultimately, the annexation of Texas did lead to war with Mexico, but American victory in the Mexican–American War (1846-1848) established the Rio Grande as Texas’s southern border in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The U.S. also gained all of what had been northern Mexico with land to the west that makes up the states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, California and Wyoming today.

The 1861 Constitution When the Supreme Court ruled that the national government—Congress specifically—lacked the authority under the U.S. Constitution to regulate slavery, fears that slavery was now a national institution gave rise to the abolition movement. The election of Abraham Lincoln on an anti-slavery platform intensified fear in the slave states that the new Republican majority would end slavery. Voices emerged claiming that Texas should shift allegiance from the United States of America to a proposed Confederate States of America. The movement towards secession in Texas was delayed because of constitutional rules. A Convention could only be called by the legislature, but the legislature was not in session. Only the governor could call a special session, and Governor Sam Houston was opposed to secession, so refused to call a Convention hoping the drive to secession would wane. It did not. A Convention was eventually called, and delegates to the Convention were selected in public meeting by a voice vote to discourage Unionists from attending. The strongly pro-secession Convention produced A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union. The principle complaint in the document was the threat posed to the institution of slavery, after being promised the ability to maintain it as a condition of entering the Union.

A committee on public safety was established and authorized to seize all federal property in Texas. Texas sent seven members to Alabama to create the Confederate States of America. All current officers were made to swear loyalty oaths to the Confederacy. Governor Sam Houston refused to take the oath and claimed the actions were illegal. The governorship was then vacated by Convention delegates and Sam Houston was replaced with Lieutenant Governor Edward Clark, whose constitutional role it was to fill the vacancy.

The 1861 Constitution is substantively the same as that of 1845. The major change was the change from an affiliation with the United States of American to the Confederate States of America and the strengthening of laws that protected the institution of slavery. No major Articles were added or deleted. The individual property rights of the slave-owner was prioritized. No law could be passed about emancipation. Individuals could not free their own slaves. Immigration of slaves from other states could not be limited. Enslaved people continued to have the right to jury trials, punished as they would be against a White victim, “except in case of insurrection by such slave.”28 But to this was added: “or rape on a white female.”29 The nature of the changes make clear that the principle concern of the members of the secession Convention was to ensure the preservation of slavery.

Then came the rebellion. The question about the legality of slavery, and the right of secession, was answered by the Civil War. The unsuccessful end of the war for the Confederacy meant that Texas would remain—and would always be—a state within the United States of America.

Reconstruction: The Constitutions of 1866, 1869, and 1876

The failed attempt to break with the United States led to a rapid turnover of constitutions in a ten year period. All rebel states were briefly controlled by the national government until each developed a constitution that would be satisfactory to the national government. For most southern states, this took a few tries. Texas’s first two attempts failed. It wasn’t until 1876 that Texas produced a document that was acceptable to both the national government and the state’s electorate.

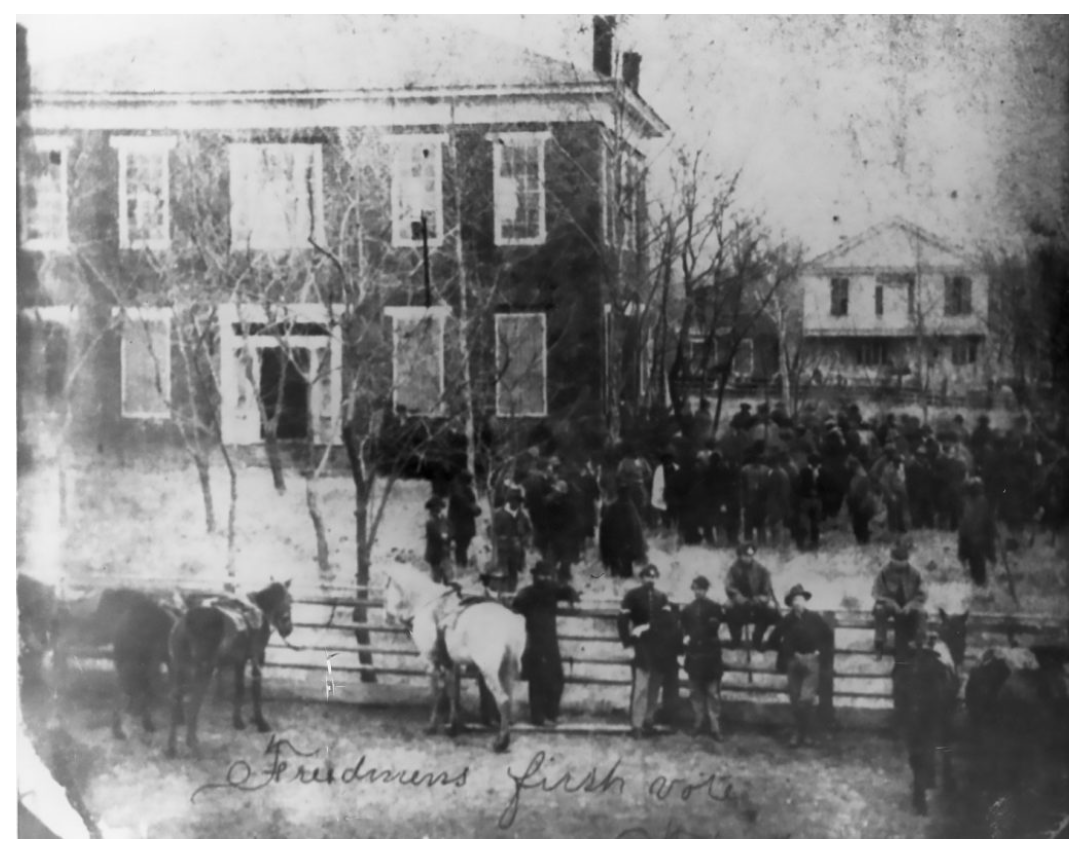

A dominant theme in all three documents was allegiance to the United States and—in the latter two—acceptance of the Thirteenth Amendment (the abolition of slavery), Fourteenth Amendment (the grant of citizenship and equality before the law—equal rights—to freedmen and women), and the Fifteenth Amendment (the extension of the right to vote to Black men) (Figure 3.3).

Similarities in structure, including limits on the power of the governing institutions, remain (Table 3.2). The major changes include the removal of the Article on Slavery, which temporarily becomes a section on Freedmen, and the Article on the Militia. In addition, Articles were created on Suffrage, and—in the 1876 version—a series of Articles noting the increase in urban areas and the need to provide services through local governments, as well as a desire to regulate the increasingly powerful business interests, particularly railroads, in the state.

Table 3.2 Outlines of Texas Constitutions, 1866-1876

| 1866 | 1869 | 1876 |

| Preamble | Preamble | Preamble |

| Article 1 - Bill of Rights | Article 1 - Bill of Rights | Article 1 - Bill of Rights |

| Article 2 - Powers | Article 2 - Powers | Article 2 - Powers |

| Article 3 - Legislative | Article 3 - Legislative | Article 3 - Legislative |

| Article 4 - Executive | Article 4 - Executive | Article 4 - Executive |

| Article 5 - Judicial | Article 5 - Judicial | Article 5 - Judicial |

| Article 6 - Militia | Article 6 - Right of Suffrage | Article 6 - Suffrage |

| Article 7 - General | Article 7 - Militia | Article 7 - Education |

| Provisions | Article 8 - Impeachment | Article 8 - Taxation |

| Article 8 - Freedmen | Article 9 - Public Schools | Article 9 - Counties |

| Article 9 - Impeachment | Article 10 - Land Office | Article 10 - Railroads |

| Article 10 - Education | Article 11 - Immigration | Article 11 - Municipal Corp |

| Article 11 - Head-Rights | Article 12 - General | Article 12 - Private Corp |

| Article 12 - Land Office | Provisions | Article 13 - Spanish and Mexican Land Titles |

| Article 13 - Proclamation | Declaration | Article 14 - Public Lands |

| Election Declaration | Article 15 - Impeachment | |

| Article 16 - General | ||

| Provisions | ||

| Article 17 - Amending the Constitution |

A key difference between the three constitutions that follow, as with all the previous documents, resulted from which groups were involved in—and restricted from—calling and participating in the respective Constitutional Conventions In addition to disputes over the status of those who had been enslaved and were now free, conflicts emerged over the power of state institutions and whether education and law enforcement was to be a state or a local function.

The 1866 Constitution News of the end of the Civil War reached Texas in May of 1865. On June 17, U.S. President Andrew Johnson appointed Andrew Jackson Hamilton provisional governor of Texas, and federal troops arrived to begin occupation of the state on June 19, which began a period known as Reconstruction. This event has been commemorated as Juneteenth, the day news of the Emancipation Proclamation reached Texas. Hamilton had been an elected official in Texas, but his support for the Union led him to flee North during the war. He had already been appointed U.S. Military Governor of Texas during the war, but the position could not be filled due to the war.

On November 15, 1865, Hamilton called for an election to be held the following January 6 to elect delegates for a Convention to meet in Austin starting February 7. Former secessionists were largely excluded from the Convention, though many were able to vote for delegates. After three days delegates agreed to take oaths (called the Ironclad Oath) to the U.S. Constitution and were then told what was to be expected of them by the U.S. government in order to be readmitted to the Union: the right of secession must be denied; the social and political status of the freedmen must be addressed fairly, which included granting them the right to sue, engage in contracts, use of courts, testify; and the Confederate debt must be repudiated.

The Convention voted on the proposed constitution on March 27, 1866. Among its key features was an increase in the powers of the governor, including a four year term, higher pay, and the ability to veto specific items from the budget. The salaries of legislators also increased. Many other aspects stayed the same. But the constitution did not incorporate a sufficient content regarding race to be accepted by the national government. The 1866 Constitution did not provide for Black male suffrage or the right for freedmen to hold office. Neither did it ratify the Thirteenth Amendment, instead simply acknowledged that it was now part of the U.S. Constitution. A census based only on the number of White people would continue to be held.

The 1866 Texas Legislature also passed the Act to Define and Declare the Rights of Persons lately known as Slaves, and Free Persons of Color. These Black Codes attempted to keep recently emancipated Black people in inferior positions politically, economically, and socially. Black people could not vote or hold office, serve on juries, or testify against Whites. Interracial marriage was made illegal. Labor laws maintained as much as possible the relationships that existed under slavery. Sharecropping, a system where families rent small portions of land with the promise that they will share a portion of their crops with the landowner, tied people legally to the land in order to ensure that they did not become economically independent. Agreements for apprenticeship or labor could be enforced with violence, and Black farmers who strayed from their land could lose all rights to the proceeds of their labor.

The 1866 Constitution was invalidated after the election of 1866 by the so called Radical Republicans who had increased their power in the United States Congress. Radical Republicans had a more punitive attitude towards the southern states. In 1867, Congress passed a series of Reconstruction Acts. These Acts divided the South into military districts with Texas placed in the fifth district with Louisiana. They made full readmission—which included the right of representation in Congress—dependent upon ratifying the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments and establishing universal suffrage for adult Black men, as well as rudimentary civil rights for freedmen and women. The state was also required to hold another to Convention to write an appropriate constitution and to impose voter registration. The U.S. Army not only kept the peace but determined acceptable office holders.

The commander of the Fifth Military District—Philip Henry Sheridan—called an election for early February 1868 to determine whether a Convention should be held, and if so, who would be the delegates to the Convention. Black voters were eligible to vote, and overwhelmingly voted to support the calling of the Convention. The legitimacy of the vote was made suspect by the large number of people who failed to vote, including a sizable number of Whites. Ten of the ninety delegates were Black, and only six had been members of the 1866 Convention. Deep divisions within the various factions made the Convention unproductive and resulted in an incomplete product.

The 1869 Constitution This is the most unusual of the Texas constitutions as it was influenced heavily by the national forces that were in control of the state at the time. These forces were driven in part by the insufficiency, from the point of view of the national government, of the 1866 Constitution. Especially problematic was the unacceptable exclusion of African Americans from the rights of citizenship. The 1869 document contained more forceful language against secession, greater protections for freedmen, and limits on local power, as localities were believed to be the source of racial hostility.

While unpopular with Whites in the state, the constitution was sufficient to readmit Texas to the Union and allow Texas voters to participate in the 1872 presidential election. The document contained language and institutions very different from that found in other constitutions. The Bill of Rights, for example, began by addressing “the heresies of nullification and secession,”30 and declaring the supremacy of the U.S. Constitution:

The Constitution of the United States, and the laws and treaties made, and to be made, in pursuance thereof, are acknowledged to be the supreme law; that this Constitution is framed in harmony with, and in subordination thereto; and that the fundamental principles embodied herein can only be changed, subject to the national authority.31

Just as significant was the centralization of powers in the state government—particularly in education and law enforcement. Centralization increased the executive authority, as did the expansion of the governor’s appointment powers. Equality before the law and universal suffrage for adult men, Black and White, was established. School attendance, for both Black and White children, was made compulsory.

Many of the provisions for former freedmen and women proved unpopular with ex-Confederates, who had not participated in the formation of this constitution. In addition to the ever present drive to limit Black equality, education, and suffrage, opposition emerged to the taxes required to support statewide law enforcement and education. Proponents of local government pushed back against effort to limit their ability to govern themselves as they chose. Their efforts to oppose these measures would be aided by the end of Reconstruction, and the removal of the federal troops necessary to implement the measures contained in the 1869 Constitution.

The 1876 Constitution Pro-Union southerners—most notably E.J. Davis who served as governor from 1870 to 1874—dominated Texas government under the 1869 Constitution, but after Reconstruction, ex-Confederates were resurgent and began to check the state power used to enforce civil rights for African Americans. The creation of the Texas State Police was especially controversial since it included Black police officers and was granted extra powers to address racially based crimes. These were tough to enforce in small local areas, so officers were granted the power to move defendants across county lines, which is unconstitutional. The creation of the police was also constitutionally suspect since in the Texas Senate senators opposed to the creation of the police were arrested.

Opposition to Davis’s actions, and the promotion of civil rights in general, benefitted the Democratic Party. They worked to weaken, then to replace, the 1869 Constitution, and were able to regain control of the legislative and executive branches of Texas government following the election of 1874 (Figure 3.4).

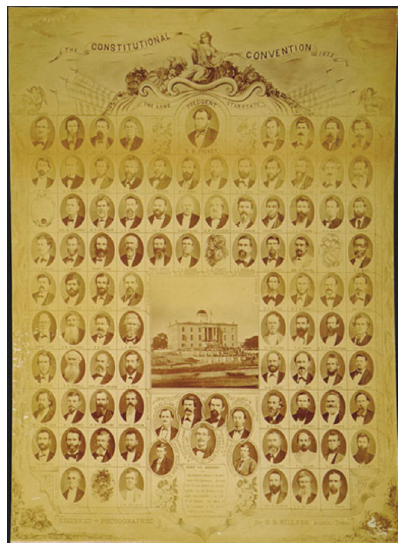

A Constitutional Convention was called in 1875 with most of the delegates Anglo Democrats. Only fifteen Republicans and six African Americans participated. The dominant political force in the Convention was the Grange—a coalition that promoted the interests of farmers in the mid-1870s. Its members were elected to almost half the delegate positions available in the 1875 Constitutional Convention (Figure 3.5). They drove much of what would be included in the ratified version of the constitution, especially checks on both public and private power.

The new constitution cut some gubernatorial powers (certain appointments and the declaration of martial law), state salaries, as well as expenditures. The power that the governor had over the executive branch was limited by creating independently elected executive positions—the plural executive—the governor had no control over and who the governor had to share executive power with. Limits were placed on the amount of time the legislature could meet in regular session, and special sessions were subject to the approval of the governor. The constitution also returned the school system to local control. And it replaced the declaration of the U.S. Constitution’s supremacy in the 1869 Constitution with a statement on the “essential principles of liberty and free government”:

Texas is a free and independent State, subject only to the Constitution of the United States; and the maintenance of our free institutions and the perpetuity of the Union depend upon the preservation of the right of local self-government unimpaired to all the States.32

Private powers were limited by the creation of Articles allowing for the regulation of rapacious railroads and private corporations, a major concern for the Grange as farmers relied on railroads to get their goods to market. Homestead protection—stemming from Spanish law—was retained. The banking industry was limited. State banks were abolished. Maximum rates of interest were established, and land speculation was checked. In addition, state debt was severely limited, which curtails the ability of the state to develop the infrastructure necessary for commercial activity or respond to a natural disaster.

The powers of government were thus strictly defined and limited. Many procedural details having to do with legislative processes and the design of the courts were laid out in the constitution, thereby making them difficult to modify. Judges were to be elected to office for limits periods, making them subject to the will of the majority—and calling into questions their independence from politics. While the state retained the power to pass laws regarding law enforcement both in terms of the penal code and criminal and civil procedures. The implementation of the law was returned to the local level by officials elected by the local electorate.

The principles of individual liberty, local control, and limited government laid down in the 1876 continue to be part of Texas’s political culture to this day.

3. Tex. Const. art. XVI, § 49, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ral-provisions.

- Tex. Const. art. XVI § 52, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...76-en/article- 16-general-provisions.

- Davy Crockett, letter to his children, Jan. 9, 1836, https://officialalamo.medium.com/texas- the-garden-spot-of-the-world-29f1951ff799.

- Texas General Land Office, “Mexican Land Policy and the First Empresario Colony,” History of Texas Public Lands, revised March 2018, https://www.glo.texas.gov/history/ar...blic-lands.pdf.

- Mimi Swartz, “Old Mother Houston: Is Charlotte Allen Houston’s True Founder?” Texas Monthly, Jan. 2014, https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-cul...other-houston/; Maggie Gordon, “Houston’s Forgotten Founder: Without Charlotte Allen, We Probably Wouldn’t Be Here Today,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 10, 2017, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/loc...r-10989893.php.

- Swartz, “Old Mother Houston?” https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-cul...other-houston/; Gordon, “Houston’s Forgotten Founder,” https://www.houstonchronicle.com/loc...r-10989893.php.

- Emily M. Austin Bryan to Stephen F. Austin (letter), Sept. 28, 1823, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67...%20M.%20Austin.

- Augustin de Iturbide and Vincente Guerrero, Plan of the Three Guarantees, 1821, https://www.historiacultural.com/201...21-mexico.html. The revolutionary proclamation declared that Mexico would become a constitutional monarchy.

- Tex. Const., General Provisions, art. II, 1836, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ral-provisions.

- Texas Declaration of Independence, 1836, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/texdec.asp.

- Texas Declaration of Independence, 1836, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/texdec.asp.

- Texas Declaration of Independence, 1836, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/texdec.asp.

- Texas Declaration of Independence, 1836, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/texdec.asp.

- Texas Declaration of Independence, 1836, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/texdec.asp.

- Texas Const. art. I, § 20, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...6-en/preamble- article-1-bill-rights.

- J E. Ericson and Mary P Winston, "Civil Law and Common Law in Early Texas," East Texas Historical Journal 2, no 1/7 (1964), https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol2/iss1/7.

- Tex. Const. art. IV, § 13, 1836, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...cle-4-judicial.

- Tex. Const. General Provisions, § 6, 1836, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ral-provisions.

- Tex. Const. General Provisions, § 9, 1836, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ral-provisions.

- Tex. Const. General Provisions, § 9, 1836, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ral-provisions.

- Tex. Const. General Provisions, § 10, 1836, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ral-provisions.

-

Resolution Annexing Texas to the United States,

Mar. 1, 1845, http://jackiewhiting.net/Collab/West/Annex.htm. - Tex. Const. art. III, § 2 and 29, 1845, http://www.afrotexan.com/laws/constitution_tex.htm.

- Tex. Const. art. VIII, § 2, 1845, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ticle-8-slaves.

- Tex. Const. art. VIII, § 3., 1845, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ticle-8-slaves.

- Tex. Const. art. VIII, § 5, 1861, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ticle-8-slaves.

- Tex. Const. art. VIII, § 5, 1861, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...ticle-8-slaves.

- Tex. Const, art. I, 1869, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...-1-bill-rights.

- Tex. Const. art. I § 1, 1869, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/const...-1-bill-rights.

- Tex. Const. art. I, § 1, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/c.php...3324&p=5803233.