9: The Evolution of the Law in Texas

- Page ID

- 129191

After you read this chapter, you should be able to:

- Trace the historical evolution of Texas courts.

- Identify the types and sources of law in Texas.

- Describe how state courts are structured in Texas.

- Compare the judicial procedures associated with civil and criminal processes.

- Evaluate the arguments around partisan elections.

James Collingsworth and Wallace Jefferson, ironic historical brothers, shared only one attribute—both were attorneys—but in almost every other way, they were diametric opposites. One was born beyond Texas’s borders in a slave-holding state. The other was the descendant of slaves and a lifelong resident of the state. One served honorably in the military, then held a variety of public service posts at the local community and higher government levels. The other build no such record other than as a volunteer for service, nonprofit, and charitable organizations. Despite their differences, both men eventually held the highest judicial position on the Supreme Court of Texas. They were two very different men, bound by one historical commonality.

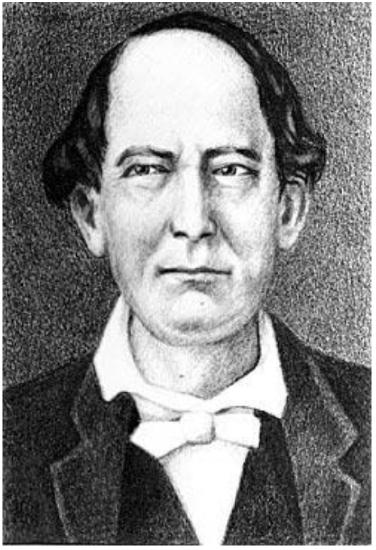

James Collingsworth (Figure 9.1) was born in Davidson County, Tennessee, in 1806, where he received his education. He studied law and in 1826 was admitted to the bar in his home state. He served as a federal attorney from 1829 to 1834. While in Tennessee, he befriended Sam Houston and Andrew Jackson. Collingsworth moved to Texas in 1834 and started his private law practice in Matagorda. He became an important figure in the Texas Revolution and a leader in the Republic of Texas. He organized a successful company of men during the Goliad Campaign of 1835, capturing the first Mexican military installation during the revolution. He received promotions and accolades for his bravery both during and after the decisive Battle of San Jacinto, where Texas won its independence from Mexico. As a result of his military service, Collingsworth was chosen as one of the signers of the Republic’s peace treaty with Santa Anna.1

Collingsworth was a public servant long before his ascension to the bench. He was a representative to the Convention of 1836, where he introduced a resolution to name Sam Houston as commander in chief of the Texas Army. He signed the Declaration of Independence and served on the committee that drafted the constitution of the new Republic of Texas, which established a court system and provided for a supreme court. The Texas Constitution also contains basic principles for the operation of the state government and legal system. It separates the powers of the government by dividing it into three distinct branches or departments:

legislative, executive, and judicial. Even though the judicial branch is the smallest of these three branches, it serves the very critical role of interpreting the law and resolving legal disputes. The judicial branch of Texas government includes the court system of the state and all judicial agencies, such as the Office of Court Administration.2

It is undisputed that Collingsworth believed that slavery should be allowed in Texas and that “persons of African derivation and that all persons of that description [now] in Texas and held as Slaves [were to] be respected as the property of their respective owners.”3 At its first session in December 1836, the Congress of the Republic elected Collingsworth as chief justice.4

Although he was the court’s first justice, his death preceded the actual opening session of the court, and he never wrote an opinion on behalf of the state’s citizens. The 1876 law establishing Collingsworth County (original population, six) misspelled Collinsworth’s name in the process. Collinsworth’s current monument in Houston’s Founders Memorial Park does spell his name correctly. However, the stone memorial was placed “at random” in 1936 (not 1931, as almost universally stated). His actual gravesite is unmarked.5

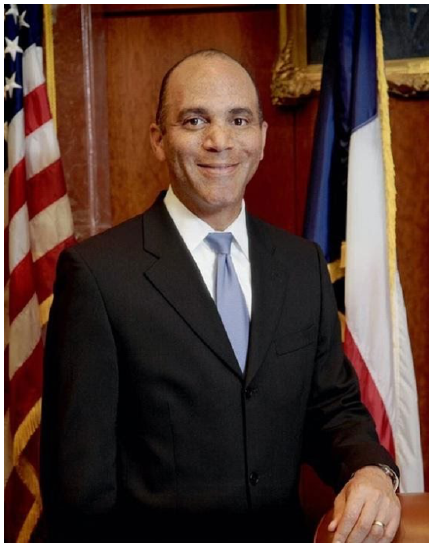

Wallace Jefferson (Figure 9.2) is the great-great-great grandson of Shedrick Willis, an enslaved person who was owned by a Waco, Texas, judge before the Civil War. After the war, Willis served on the Waco City Council for two terms. Jefferson was born in San Antonio, where he graduated from a local high school. He completed his undergraduate in Michigan and earned his law degree from the University of Texas School of Law. After practicing law as an appellate attorney in a local law firm, Jefferson cofounded an appellate law firm that became one of the most preeminent appellate practices in Texas.6

Jefferson made history as the first African-American to become first a justice and then chief justice of the Supreme Court of Texas. Republican Governor Rick Perry initially appointed Jefferson as a justice to the court in 2001 to fill the vacancy left by another San Antonio native, Alberto R. Gonzales. Jefferson was then elected to the same post in 2002, At the age of forty- one, Jefferson became the twenty-sixth chief justice of the court when he was appointed to that position after Chief Justice Tom Phillips retired from the court in 2004. In November 2006, Jefferson was elected to that post, receiving more votes than any other non-federal candidate for statewide office. Not surprisingly, Jefferson was overwhelmingly reelected, and he remained in that position until 2013.7

Evolution of the Texas Court System

Since its inception, under Spanish and then Mexican rule, the area now known as Texas has undergone a judicial history that can be characterized as a haphazard evolution. Even before Texas became its own Republic, Texas had a system of courts. As citizens of Mexico, Texans were given access to state and local courts created by the Mexican Constitutions of 1824 and 1827. Judicial power was vested in the municipal alcalde, a name borrowed from an Arabic word meaning “the judge.” An alcade was an elected official who held executive, legislative and judicial duties in and around a municipality. His decisions were not final, however, and could be appealed to the ayuntamiento, the judicial mayor, who served as chief assistant to the governor, or to the governor himself. Appeals were handled only in Saltillo, over 600 miles from the northern parts of the state.8

Following the Texas Revolution, when Texas became an independent republic in 1836, the newly independent government established a judicial system based on Anglo-American common law. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas designated the Supreme Court of Texas (as the highest court in the land. The court consisted of a chief justice and eight associate justices. The associate justices also served as district judges of the newly created eight district courts of Texas. The district judges, whose first session was January 13, 1840, served with the chief justice as associate justices from 1840-1845 (when Texas was admitted into the United States). Since then, Texas’s court system has evolved in a piecemeal fashion.

The Supreme Court was restructured at least four times. Some courts (called commissions) were created on three occasions and subsequently eliminated, never to be seen again. The number of judges of various courts at multiple levels has also changed, some as late at the 1980s. The state’s high court evolved from a nomadic collection of judges—traveling to various Texas cities—to a court that finally settled at its current, permanent home in Austin. Its part-time, nine-month meetings ultimately became annual, full-time sessions. An additional court—the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals—was added to relieve the burden of the Supreme Court, which was overwhelmed with cases on appeal. When that strategy proved futile, even more intermediate appellate courts—the courts of appeals—were created as part of yet another restructuring effort. With these changes came modifications in the jurisdiction of the state’s non-trial, appellate courts.

No one could envision the possibility that the current court system would include sixteen appellate courts—fourteen courts of appeals, the Texas Supreme Court and the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals—as well as over 1,800 county administered courts and nearly 950 municipal courts overseen by over 3,200 justice and judges. Even though the structure of the state’s court system may not substantially change, one thing about the judiciary is a certainty: demographic statistics indicate that the state’s population increased nearly seventeen percent during the ten years since completion of the 2010 Census (to approximately 29.5),9 and the 2020 Census is expected to support demographer predictions of more growth, Recent trends lead demographers to predict that the number of people in Texas will increase to 54.4 million people by 2050.10 The courts’ workloads will also dramatically increase because of the anticipated litigiousness of the state’s ever growing population. As the number of residents exponentially increases, therefore, so too must the number of courts that have yet to be created by the Texas legislature.

1. Joe E. Ericson, “Collinsworth, James (1806–1838),” Texas State Historical Association Handbook, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...insworth-james.

2. Office of Court Administration, The Texas Judicial System (Sept. 2014), https://www.txcourts.gov/media/67544...rint102714.pdf.

3. David G. Burnet to James Collinsworth and Peter W. Grayson (letter), May 26, 1836, in the Texas Secretary of State’s Diplomatic Correspondence of Texas, vol. 2, (Washington, D.C.: GPO), 91. Ericson, “Collinsworth,” https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/...insworth-james.

4. James W. Paulsen, “Reconsidering James Collinsworth, the Texas Supreme Court’s First Chief Justice,” Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society 7, no. 3 (spring 2018): 84, https://www.texascourthistory.org/Co...ing%202018.pdf

5. “The Honorable Wallace B. Jefferson Senior Trustee,” University of Texas Law School Foundation, https://utlsf.org/trustee/wallace-jefferson/.

6. “The Honorable Wallace B. Jefferson,” https://utlsf.org/trustee/wallace-jefferson/.

7. Jason Boatright, “Alcaldes in Austin’s Colony, 1821-1835,” Journal of the Supreme Court Historical Society 7, no. 3 (spring 2018): 26–50, https://www.texascourthistory.org/Co...ing%202018.pdf.

8. Lloyd B. Potter and Nazrul Hoque, Texas Population Projections 2010 to 2050, University of Texas at San Antonio - Texas Demographic Center (2019), https://demographics.texas.gov/Resou...tionsBrief.pdf.

9. Potter and Hoque, “Population Projections,” https://demographics.texas.gov/Resou...tionsBrief.pdf.

10. “Case Law,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/case_law.