21.6: Situational Determinants Of Conformity

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 75772

The studies of Asch, Sherif, and Moscovici demonstrate the extent to which individuals—both majorities and minorities— can create conformity in others. Furthermore, these studies provide information about the characteristics of the social situation that are important in determining the extent to which we conform to others. Let’s consider some of those variables.

The Size of the Majority

As the number of people in the majority increases, relative to the number of persons in the minority, pressure on the minority to conform also increases (Latané, 1981; Mullen, 1983). Asch conducted replications of his original line-judging study in which he varied the number of confederates (the majority subgroup members) who gave initial incorrect responses from 1 to 16 people, while holding the number in the minority subgroup constant at 1 (the single research par- ticipant). You may not be surprised to hear the results of this research: When the size of the majorities got bigger, the lone participant was more likely to give the incorrect answer.

Increases in the size of the majority increase conformity, regardless of whether the conformity is informational or normative. In terms of informational conformity, if more people express an opinion, their opinions seem more valid. Thus bigger majorities should result in more informational conformity. But larger majorities will also produce more normative conformity because being different will be harder when the majority is bigger. As the majority gets bigger, the individual giving the different opinion becomes more aware of being different, and this produces a greater need to conform to the prevailing norm.

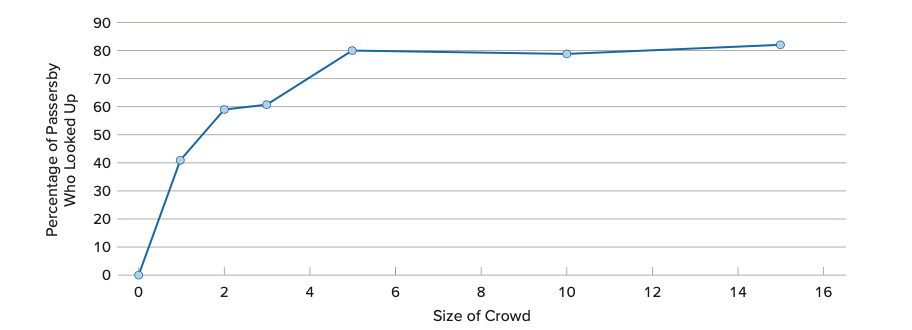

Although increasing the size of the majority does increase conformity, this is only true up to a point. The increase in the amount of conformity that is produced by adding new members to the majority group (known as the social impact of each group member) is greater for initial majority members than it is for later members (Latané, 1981). This pattern is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), which presents data from a well- known experiment by Stanley Milgram and his colleagues (1969) that studied how people are influenced by the behavior of others on the streets of New York City.

Milgram had confederates gather in groups on 42nd Street in New York City, in front of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, each looking up at a window on the sixth floor of the building. The confederates were formed into groups ranging from one to 15 people. A video camera in a room on the sixth floor above recorded the behavior of 1,424 pedestrians who passed along the sidewalk next to the groups.

As you can see in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), larger groups of confederates increased the number of people who also stopped and looked up, but the influence of each additional confederate was generally weaker as size increased. Groups of three con- federates produced more conformity than did a single person, and groups of five produced more conformity than groups of three. But after the group reached about six people, it didn’t really matter very much. Just as turning on the first light in an initially dark room makes more difference in the brightness of the room than turning on the second, third, and fourth lights does, adding more people to the majority tends to pro- duce diminishing returns—less effect on conformity.

Group size is an important variable that influences a wide variety of behaviors of the individuals in groups. People leave proportionally smaller tips in restaurants as the number in their party increases, and people are less likely to help as the number of bystanders to an incident increases (Latané, 1981). The number of group members also has an important influence on group performance: As the size of a working group gets larger, the contributions of each individual member to

the group effort become smaller. In each case, the influence of group size on behavior is found to be similar to that shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

As you can see in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), the effect of adding new individuals to the group eventually levels off entirely, such that adding more people to the majority after that point makes no meaningful difference in the amount of conformity. This peak usually occurs when the majority has about four or five persons. One reason that the impact of new group members decreases so rapidly is because as the number in the group increases, the individuals in the majority are soon seen more as a group rather than as separate individuals. When there are only a couple of individuals expressing opinions, each per- son is likely to be seen as an individual, holding his or her own unique opinions, and each new individual adds to the impact. As a result, two people are more influential than one, and three more influential than two. However, as the number of individuals grows, and particularly when those individuals are perceived as being able to communicate with each other, the individuals are more likely to be seen as a group rather than as individuals. At this point, adding new members does not change the perception; regardless of whether there are four, five, six, or more members, the group is still just a group. As a result, the expressed opinions or behaviors of the group members no longer seem to reflect their own characteristics, so much as they do that of the group as a whole, and thus increasing the number of group members is less effective in increasing influence (Wilder, 1977).

The Unanimity of the Majority

Although the number of people in the group is an important determinant of conformity, it cannot be the only thing—if it were, minority influence would be impossible. It turns out that the consistency or unanimity of the group members is even more important. In Asch’s study, as an example, conformity occurred not so much because many confederates gave a wrong answer but rather because each of the confederates gave the same wrong answer. In one follow-up study that he conducted, Asch increased the number of confederates to 16 but had just one of those confederates give the correct answer. He found that in this case, even though there were 15 incorrect and only one correct answer given by the confederates, conformity was nevertheless sharply reduced—to only about 5% of the participants’ responses. And you will recall that in the minority influence research of Moscovici, the same thing occurred; conformity was only observed when the minority group members were completely consistent in their expressed opinions.

Although you might not be surprised to hear that conformity decreases when one of the group members gives the right answer, you may be more surprised to hear that conformity is reduced even when the dissenting confederate gives a different wrong answer. For example, conformity is reduced dramatically in Asch’s line-judging situation, such that virtually all participants give the correct answer (assume it is line 3 in this case) even when the majority of the con- federates have indicated that line 2 is the correct answer and a single confederate indicates that line 1 is correct. In short, conformity is reduced when there is any inconsistency among the members of the majority group—even when one member of the majority gives an answer that is even more incorrect than that given by the other majority group members (Allen & Levine, 1968).

Why should unanimity be such an important determinant of conformity? For one, when there is complete agreement among the majority members, the individual who is the target of influence stands completely alone and must be the first to break ranks by giving a different opinion. Being the only person who is different is potentially embarrassing, and people who wish to make a good impression on, or be liked by, others may naturally want to avoid this. If you can convince your friend to wear blue jeans rather than a coat and tie to a wedding, then you’re naturally going to feel a lot less conspicuous when you wear jeans too.

RESEARCH FOCUS

How Task importance and Confidence influence Conformity

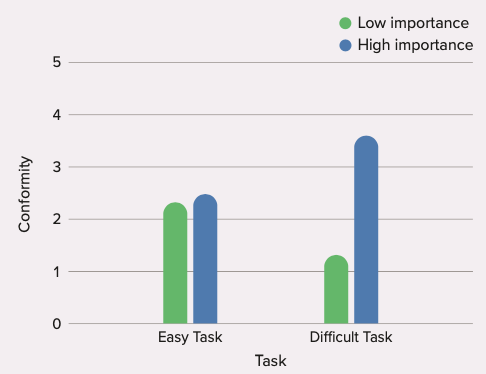

The joint influence of an individual’s confidence in his or her beliefs and the importance of the task was demonstrated in an experiment conducted by Baron et al. (1996) that used a slight modification of the Asch procedure to assess conformity. Participants completed the experiment along with two other students, who were actually experimental confederates. The participants worked on several different types of trials, but there were 26 that were relevant to the conformity predictions. On these trials, a photo of a single individual was presented first, followed immediately by a “lineup” photo of four individuals, one of whom had been viewed in the initial slide (but who might have been dressed differently).

The participants’ task was to call out which person in the lineup was the same as the original individual using a number between 1 (the person on the left) and 4 (the person on the right). In each of the critical trials the two confederates went before the participant and they each gave the same wrong response.

Two experimental manipulations were used. First, the researchers manipulated task importance by telling some participants (the high importance condition) that their performance on the task was an important measure of eyewitness ability and that the participants who performed most accu- rately would receive $20 at the end of the data collection. (A lottery using all the participants was actually held at the end of the semester, and some participants were paid the

Second, when there is complete agreement—remember the consistent minority in the studies by Moscovici—the participant may become less sure of his or her own perceptions. Because everyone else is holding the exact same opinion, it seems that they must be correctly responding to the external reality. When such doubt occurs, the individual may be likely to conform due to informational conformity. Finally, when one or more of the other group members gives a different answer than the rest of the group (so that the unanimity of the majority group is broken), that person is no longer part of the group that is doing the influencing and becomes (along with the participant) part of the group being influenced. You can see that another way of describing the effect of unanimity is to say that as soon as the individual has someone who agrees with him or her that the others may not be correct (a supporter or ally), then the pressure to con- form is reduced. Having one or more supporters who challenge the status quo validates one’s own opinion and makes disagreeing with the majority more likely (Allen, 1975; Boyanowsky & Allen, 1973).

The importance of the Task

Still another determinant of conformity is the perceived importance of the decision. The studies of Sherif, Asch, and Moscovici may be criticized because the decisions that the participants made—for instance, judging the length of lines or the colors of objects—seem rather trivial. But what would happen when people were asked to make an important decision? Although you might think that conformity would be less when the task becomes more important (perhaps because people would feel uncomfortable relying on the judgments of others and want to take more responsibility for their own decisions), the influence of task importance actually turns out to be more complicated than that.

$20.) Participants in the low-importance condition, on the other hand, were told that the test procedure was part of a pilot study and that the decisions were not that important. Second, task difficulty was varied by showing the test and the lineup photos for 5 and 10 seconds, respectively (easy condition) or for only 1⁄2 and 1 second, respectively (difficult condition). The conformity score was defined as the number of trials in which the participant offered the same (incorrect) response as the confederates.

As you can see in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), an interaction between task difficulty and task importance was observed. On easy tasks, participants conformed less to the incorrect judg- ments of others when the decision had more important con- sequences for them. In these cases, they seemed to rely more on their own opinions (which they were convinced were correct) when it really mattered, but were more likely to go along with the opinions of the others when things were not that critical (probably normative conformity).

On the difficult tasks, however, results were the oppo- site. In this case, participants conformed more when they thought the decision was of high, rather than low, impor- tance. In these cases in which they were more unsure of their opinions and yet they really wanted to be correct, they used the judgments of others to inform their own views (informational conformity). ■

REFERENCES

Allen, V. L. (1975). Social support for nonconformity. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 8). Academic Press.

Allen, V. L., & Levine, J. M. (1968). Social support, dissent and conformity. Sociometry, 31(2), 138–149. doi.org/10.2307/2786454

Anderson, C., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2003). Emotional convergence between people over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 1054–1068. doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.84.5.1054

Asch, S. E. (1952). Social psychology. Prentice-Hall.

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 11,

32. doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1155-31

Baron, R. S., Vandello, J. A., & Brunsman, B. (1996). The forgotten

variable in conformity research: Impact of task importance on social influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(5), 915–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.915

Boyanowsky, E. O., & Allen, V. L. (1973). Ingroup norms and self-identity as determinants of discriminatory behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25(3), 408–418. doi.org/10.1037/ h0034212

Chartrand, T. L., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 893–910. doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.76.6.893

Chartrand, T. L., & Dalton, A. N. (2009). Mimicry: Its ubiquity, importance, and functionality. In E. Morsella, J. A. Bargh, & P. M. Gollwitzer (Eds.), Oxford handbook of human action (pp. 458–483). Oxford University Press.

Cialdini, R. B. (1993). Influence: Science and practice (3rd ed.). Harper Collins.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. doi.org/10.1037/ 0022-3514.58.6.1015

Crano, W. D., & Chen, X. (1998). The leniency contract and persistence of majority and minority influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1437–1450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1437

Dalton, A. N., Chartrand, T. L., & Finkel, E. J. (2010). The schema-driven chameleon: How mimicry affects executive and self-regulatory resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017629

Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51(3), 629–636. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/h0046408

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups. Harper.

Hardin, C., & Higgins, T. (1996). Shared reality: How social verification makes the subjective objective. In R. M. Sorrentino & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 28–84). Guilford.

Hogg, M. A. (2010). Influence and leadership. In S. F. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 1166– 1207). Wiley.

Jacobs, R. C., & Campbell, D. T. (1961). The perpetuation of an arbitrary tradition through several generations of a laboratory microculture. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(3), 649–658. https:// doi.org/10.1037/h0044182

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356. doi.org/10.1037/ 0003-066X.36.4.343

MacNeil, M. K., & Sherif, M. (1976). Norm change over subject generations as a function of arbitrariness of prescribed norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(5), 762–773. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.5.762

Martin, R., & Hewstone, M. (2003). Majority versus minority influence: When, not whether, source status instigates heuristic or systematic processing. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(3), 313–330. doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.146

Martin, R., Martin, P. Y., Smith, J. R., & Hewstone, M. (2007). Majority versus minority influence and prediction of behavioral intentions and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(5), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.06.006

Milgram, S., Bickman, L., & Berkowitz, L. (1969). Note on the drawing power of crowds of different size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(2), 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0028070

Moscovici, S., Lage, E., & Naffrechoux, M. (1969). Influence of a consistent minority on the responses of a majority in a color perception task. Sociometry, 32(4), 365–379. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2786541

Mugny, G., & Papastamou, S. (1981). When rigidity does not fail: Individualization and psychologicalization as resistance to the diffusion of minority innovation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 43–62. doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420100104

Mullen, B. (1983). Operationalizing the effect of the group on the individual: A self-attention perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19(4), 295–322. doi.org/10.1016/ 0022-1031(83)90025-2

Nemeth, C. J., & Kwan, J. L. (1987). Minority influence, divergent thinking, and the detection of correct solutions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17(9), 788–799. doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1987. tb00339.x

Rohrer, J. H., Baron, S. H., Hoffman, E. L., & Swander, D. V. (1954). The stability of autokinetic judgments. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4, Pt. 1), 143–146. doi.org/10.1037/ h0060827

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. Harper & Row. Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways. Ginn.

Tickle-Degnen, L., & Rosenthal, R. (1990). The nature of rapport and its nonverbal correlates. Psychological Inquiry, 1(4), 285–293. https:// doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0104_1

Tickle-Degnen, L., & Rosenthal, R. (Eds.). (1992). Nonverbal aspects of therapeutic rapport. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Turner, J. C. (1991). Social influence. Brooks Cole.

Wilder, D. A. (1977). Perception of groups, size of opposition, and social influence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(77)90047-6