6.1: Chapter 10- Physical Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Page ID

- 55299

Chapter 10 Learning Objectives

- Summarize overall physical growth during infancy.

- Describe the growth in the brain during infancy.

- Explain infant sleep.

- Identify newborn reflexes.

- Compare gross and fine motor skills.

- Contrast the development of the senses in newborns.

- Describe the habituation procedure.

- Explain the merits of breastfeeding and when to introduce more solid foods.

- Discuss the nutritional concerns of marasmus and kwashiorkor.

Overall Physical Growth

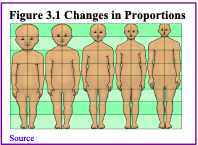

Body Proportions

The Brain in the First Two Years

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Social_Work_and_Human_Services/Remix:_Human_Behavior_and_the_Social_Environment_I_(Tyler)/06:_Development_in_Infancy_and_Toddlerhood/6.01:_Chapter_10-_Physical_Development_in_Infancy_and_Toddlerhood), /content/body/div[4]/p[1]/@function, line 1, column 1

where neural connections are reduced thereby making those that are used much stronger. It is thought that pruning causes the brain to function more efficiently, allowing for mastery of more complex skills (Kolb & Whishaw, 2011). The experience will shape which of these connections are maintained and which of these are lost. Ultimately, about 40 percent of these connections will be lost (Webb, Monk, and Nelson, 2001). Blooming occurs during the first few years of life, and pruning continues through childhood and into adolescence in various areas of the brain.

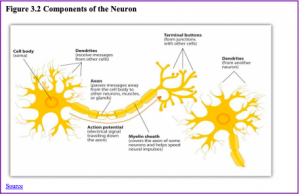

a coating of fatty tissues around the axon of the neuron (Carlson, 2014). Myelin helps insulate the nerve cell and speed the rate of transmission of impulses from one cell to another. This enhances the building of neural pathways and improves coordination and control of movement and thought processes. The development of myelin continues into adolescence but is most dramatic during the first several years of life.

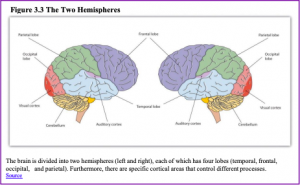

the thin outer covering of the brain involved in voluntary activity and thinking. The cortex is divided into two hemispheres, and each hemisphere is divided into four lobes, each separated by folds known as fissures. If we look at the cortex starting at the front of the brain and moving over the top (see Figure 3.3), we see first the frontal lobe (behind the forehead), which is responsible primarily for thinking, planning, memory, and judgment. Following the frontal lobe is the parietal lobe, which extends from the middle to the back of the skull and which is responsible primarily for processing information about touch. Next is the occipital lobe, at the very back of the skull, which processes visual information. Finally, in front of the occipital lobe, between the ears, is the temporal lobe, which is responsible for hearing and language (Jarrett, 2015).

Although the brain grows rapidly during infancy, specific brain regions do not mature at the same rate. Primary motor areas develop earlier than primary sensory areas, and the prefrontal cortex, that is located behind the forehead, is the least developed (Giedd, 2015). As the prefrontal cortex matures, the child is increasingly able to regulate or control emotions, to plan activities, strategize, and have better judgment. This is not fully accomplished in infancy and toddlerhood but continues throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Lateralization is the process in which different functions become localized primarily on one side of the brain. For example, in most adults the left hemisphere is more active than the right during language production, while the reverse pattern is observed during tasks involving visuospatial abilities (Springer & Deutsch, 1993). This process develops over time, however, structural asymmetries between the hemispheres have been reported even in fetuses (Chi, Dooling, & Gilles, 1997; Kasprian et al., 2011) and infants (Dubois et al., 2009).

Lastly, neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to change, both physically and chemically, to enhance its adaptability to environmental change and compensate for an injury. The control of some specific bodily functions, such as movement, vision, and hearing, is performed in specified areas of the cortex, and if these areas are damaged, the individual will likely lose the ability to perform the corresponding function. The brain’s neurons have a remarkable capacity to reorganize and extend themselves to carry out these particular functions in response to the needs of the organism, and to repair any damage. As a result, the brain constantly creates new neural communication routes and rewires existing ones. Both environmental experiences, such as stimulation and events within a person’s body, such as hormones and genes, affect the brain’s plasticity. So too does age. Adult brains demonstrate neuroplasticity, but they are influenced less extensively than those of infants (Kolb & Fantie, 1989; Kolb & Whishaw, 2011).

Infant Sleep

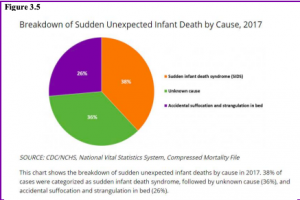

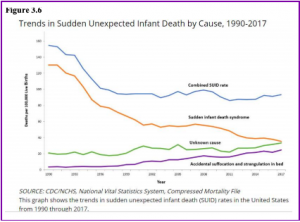

Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUID): Each year in the United States, there are about 3,500 Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUID). These deaths occur among infants less than one-year-old and have no immediately obvious cause (CDC, 2019). The three commonly reported types of SUID are:

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): SIDS is identified when the death of a healthy infant occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, and medical and forensic investigation findings (including an autopsy) are inconclusive. SIDS is the leading cause of death in Figure 3.4 75 infants 1 to 12 months old, and approximately 1,400 infants died of SIDS in 2017 (CDC, 2019). Because SIDS is diagnosed when no other cause of death can be determined, possible causes of SIDS are regularly researched. One leading hypothesis suggests that infants who die from SIDS have abnormalities in the area of the brainstem responsible for regulating breathing (Weekes-Shackelford & Shackelford, 2005).

- Unknown Cause: The sudden death of an infant less than one year of age that cannot be explained because a thorough investigation was not conducted, and the cause of death could not be determined. In 2017, 1300 infants died from unknown causes (CDC, 2019).

- Accidental Suffocation and Strangulation in Bed: Reasons for accidental suffocation include: Suffocation by soft bedding, another person rolling on top of or against the infant while sleeping, an infant being wedged between two objects such as a mattress and wall, and strangulation such as when an infant’s head and neck become caught between crib railings. In 2017, 900 infants died from accidental suffocation and strangulation.

Should infants be sharing the bed with parents?

From Reflexes to Voluntary Movements

Table 3.1 Some Common Infant Reflexes

Motor Development

from the floor and placing them in containers. By 9 months, an infant can also watch a moving object, reach for it as it approaches, and grab it.

Sensory Capacities

Vision: The womb is a dark environment void of visual stimulation. Consequently, vision is one of the most poorly developed senses at birth, and time is needed to build those neural pathways between the eyes and the brain (American Optometric Association [AOA], 2019). Newborns typically cannot see further than 8 to 10 inches away from their faces (AOA, 2019). An 8-week old’s vision is 20/300. This means an object 20 feet away from an infant has the same clarity as an object 300 feet away from an adult with normal vision. By 3-months visual acuity has sharpened to 20/200, which would allow them the see the letter E at the top of a standard eye chart (Hamer, 2016). As a result, the world looks blurry to young infants (Johnson & deHaan, 2015).

- One-month-olds have difficulty disengaging their attention and can spend several minutes fixedly gazing at a stimulus (Johnson & deHaan, 2015).

- Aslin (1981) found that when tracking an object visually, the eye movements of newborns and one-month olds are not smooth but saccadic, that is step-like jerky movements. Aslin also found their eye movements lag behind the object’s motion. This means young infants do not anticipate the trajectory of the object. By two months of age, their eye movements are becoming smoother, but they still lag behind the motion of the object and will not achieve this until about three to four months of age (Johnson & deHaan, 2015).

- Newborns also orient more to the visual field toward the side of the head, than to the visual field on either side of the nose (Lewis, Maurer, & Milewski, 1979). By two to three months, stimuli in both fields are now equally attended to (Johnson & deHaan, 2015).

Hearing: The infant’s sense of hearing is very keen at birth, and the ability to hear is evidenced as soon as the seventh month of prenatal development. Newborns prefer their mother’s voices over another female when speaking the same material (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980). Additionally, they will register in utero specific information heard from their mother’s voice.

were 7 months pregnant. The fetuses had been exposed to the stories an average of 67 times or 1.5 hours. When the experimental infants were tested, the target stories (previously heard) were more reinforcing than the novel story as measured by their rate of sucking. However, for control infants, the target stories were not more reinforcing than the novel story indicating that the experimental infants had heard them before.

the sounds that are not in the language around them diminishes rapidly (Cheour-Luhtanen, et al., 1995).

Touch and Pain: Immediately after birth, a newborn is sensitive to touch and temperature, and is also highly sensitive to pain, responding with crying and cardiovascular responses (Balaban & Reisenauer, 2013). Newborns who are circumcised, which is the surgical removal of the foreskin of the penis, without anesthesia experience pain as demonstrated by increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, decreased oxygen in the blood, and a surge of stress hormones (United States National Library of Medicine, 2016). Research has demonstrated that infants who were circumcised without anesthesia experienced more pain and fear during routine childhood vaccines. Fortunately, today many local pain killers are currently used during circumcision.

Taste and Smell: Studies of taste and smell demonstrate that babies respond with different facial expressions, suggesting that certain preferences are innate. Newborns can distinguish between sour, bitter, sweet, and salty flavors and show a preference for sweet flavors. Newborns also prefer the smell of their mothers. An infant only 6 days old is significantly more likely to turn toward its own mother’s breast pad than to the breast pad of another baby’s mother (Porter, Makin, Davis, & Christensen, 1992), and within hours of birth an infant also shows a preference for the face of its own mother (Bushnell, 2001; Bushnell, Sai, & Mullin, 1989).

Intermodality: Infants seem to be born with the ability to perceive the world in an intermodal way; that is, through stimulation from more than one sensory modality. For example, infants who sucked on a pacifier with either a smooth or textured surface preferred to look at a corresponding (smooth or textured) visual model of the pacifier. By 4 months, infants can match lip movements with speech sounds and can match other audiovisual events. Sensory processes are certainly affected by the infant’s developing motor abilities (Hyvärinen, Walthes, Jacob, Nottingham Chapin, & Leonhardt, 2014). Reaching, crawling, and other actions allow the infant to see, touch, and organize his or her experiences in new ways.

How are Infants Tested: Habituation procedures, that is measuring decreased responsiveness to a stimulus after repeated presentations, have increasingly been used to evaluate infants to study the development of perceptual and memory skills. Phelps (2005) describes a habituation procedure used when measuring the rate of the sucking reflex.

Nutrition

rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of SIDS. The USDHHS recommends that mothers breastfeed their infants until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year or two.

HIV are routinely discouraged from breastfeeding as the infection may pass to the infant. Similarly, women who are taking certain medications or undergoing radiation treatment may be told not to breastfeed (USDHHS, 2011).

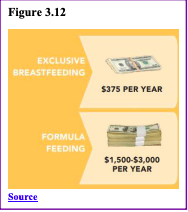

breastfeeding. Prices for a year’s worth of formula and feeding supplies can cost between $1,500 and $3000 per year (Los Angles County Department of Public Health, 2019). In addition to the formula, costs include bottles, nipples, sterilizers, and other supplies.

- can sit up without needing support

- can hold its head up without wobbling

- shows interest in foods others are eating

- is still hungry after being breastfed or formula-fed

- is able to move foods from the front to the back of the mouth

- is able to turn away when they have had enough

For many infants who are 4 to 6 months of age, breast milk or formula can be supplemented with more solid foods. The first semi-solid foods that are introduced are iron-fortified infant cereals mixed with breast milk or formula. Typically rice, oatmeal, and barley cereals are offered as a number of infants are sensitive to more wheat-based cereals. Finger foods such as toast squares, cooked vegetable strips, or peeled soft fruit can be introduced by 10-12 months. New foods should be introduced one at a time, and the new food should be fed for a few days in a row to allow the baby time to adjust to the new food. This also allows parents time to assess if the child has a food allergy. Foods that have multiple ingredients should be avoided until parents have assessed how the child responds to each ingredient separately. Foods that are sticky (such as peanut butter or taffy), cut into large chunks (such as cheese and harder meats), and firm and round (such as hard candies, grapes, or cherry tomatoes) should be avoided as they are a choking hazard. Honey and corn syrup should be avoided as these often contain botulism spores. In children under 12 months, this can lead to death (Clemson University Cooperative Extension, 2014).

Figure 3.12

Global Considerations and Malnutrition

in every 13 children in the world suffers from some form of wasting, and the majority of these children live in Asia (34.3 million) and Africa (13.9 million). Wasting can occur as a result of severe food shortages, regional diets that lack certain proteins and vitamins, or infectious diseases that inhibit appetite (Latham, 1997).

References

Ainsworth, M. (1979). Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34(10), 932-937.

Akimoto, S. A., & Sanbinmatsu, D. M. (1999). Differences in self-effacing behavior between European and Japanese Americans: Effect on competence evaluations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 159-177.

American Optometric Association. (2019). Infant vision: Birth to 24 months of age. Retrieved from https://www.aoa.org/patients-and-public/good-vision-throughout-life/childrens-vision/infant-vision-birth-to-24- months-of-age

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).

Washington, DC: Author.

Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58 10), v–165.

Aslin, R. N. (1981). Development of smooth pursuit in human infants. In D. F. Fisher, R. A. Monty, & J. W. Senders (Eds.), Eye movements: Cognition and visual perception (pp. 31– 51). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Atkinson, J., & Braddick, O. (2003). Neurobiological models of normal and abnormal visual development. In M. de Haan & M. H. Johnson (Eds.), The cognitive neuroscience of development (pp. 43– 71). Hove: Psychology Press.

Baillargeon, R. (1987. Object permanence in 3 ½ and 4 ½ year-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 22, 655-664. Baillargeon, R., Li, J., Gertner, Y, & Wu, D. (2011). How do infants reason about physical events? In U. Goswami (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. MA: John Wiley.

Balaban, M. T. & Reisenauer, C. D. (2013). Sensory development. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 1144-1147). New, York: Sage Publications.

Baldwin, D. A. (1993). Early referential understanding: Infants’ ability to recognize referential acts for what they are. Developmental Psychology, 29(5), 832–843.

Bartrip J, Morton J, & De Schonen S. (2001). Responses to mother’s face in 3-week to 5-month-old infants. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 219–232

Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Berne, S. A. (2006). The primitive reflexes: Considerations in the infant. Optometry & Vision Development, 37(3), 139-145. Bloem, M. (2007). The 2006 WHO child growth standards. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 334(7596), 705–706. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39155.658843.BE

Blossom, M., & Morgan, J. L. (2006). Does the face say what the mouth says? A study of infants’ sensitivity to visual prosody. In the 30th annual Boston University conference on language development, Somerville, MA.

Bogartz, R. S., Shinskey, J. L., & Schilling, T. (2000). Object permanence in five-and-a-half month old infants. Infancy, 1(4), 403-428.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. London: Hogarth Press. Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Bradshaw, D. (1986). Immediate and prolonged effectiveness of negative emotion expressions in inhibiting infants’ actions (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley.

Braungart-Rieker, J. M., Hill-Soderlund, A. L., &Karrass, J. (2010). Fear, anger reactivity trajectories from 4 to 16 months: The roles of temperament, regulation, and maternal sensitivity. Developmental Psychology, 46, 791-804.

Bushnell, I. W. R. (2001) Mother’s face recognition in newborn infants: Learning and memory. Infant Child Development, 10, 67-94.

Bushnell, I. W. R., Sai, F., Mullin, J. T. (1989). Neonatal recognition of mother’s face. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7, 3-15.

Bruer, J. T. (1999). The myth of the first three years: A new understanding of early brain development and lifelong learning. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Campanella, J., & Rovee-Collier, C. (2005). Latent learning and deferred imitation at 3 months. Infancy, 7(3), 243-262. Carlson, N. (2014). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Carpenter, R., McGarvey, C., Mitchell, E. A., Tappin, D. M., Vennemann, M. M., Smuk, M., & Carpenter, J. R. (2013). Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: Is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case–control studies. BMJ Open, 3:e002299. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002299

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Breastfeeding facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/facts.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Sudden unexpected infant death and sudden infant death syndrome. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/sids/data.htm

Cheour-Luhtanen, M., Alho. K., Kujala, T., Reinikainen, K., Renlund, M., Aaltonen, O., … & Näätänen R. (1995). Mismatch negativity indicates vowel discrimination in newborns. Hearing Research, 82, 53–58.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1996). Temperament: Theory and practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Chi, J. G., Dooling, E. C., & Gilles, F. H. (1977). Left-right asymmetries of the temporal speech areas of the human fetus. Archives of Neurology, 34, 346–8.

Chien S. (2011). No more top-heavy bias: Infants and adults prefer upright faces but not top-heavy geometric or face-like patterns. Journal of Vision, 11(6):1–14.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Chomsky, N. (1972). Language and mind. NY: Harcourt Brace.

Clark, E. V. (2009). What shapes children’s language? Child-directed speech and the process of acquisition. In V. C. M. Gathercole (Ed.), Routes to language: Essays in honor of Melissa Bowerman. NY: Psychology Press.

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285.

Clemson University Cooperative Extension. (2014). Introducing solid foods to infants. Retrieved from http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/nutrition/nutrition/life_stages/hgic4102.html

Cole, P. M., Armstrong, L. M., & Pemberton, C. K. (2010). The role of language in the development of emotional regulation. In S. D. Calkins & M. A. Bell (Eds.). Child development at intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 59-77). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Colvin, J.D., Collie-Akers, V., Schunn, C., & Moon, R.Y. (2014). Sleep environment risks for younger and older infants. Pediatrics Online. Retrieved from pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/07/09/peds. 2014-0401.full.pdf

de Boysson-Bardies, B., Sagart, L., & Durand, C. (1984). Discernible differences in the babbling of infants according to target language. Journal of Child Language, 11(1), 1–15.

DeCasper, A. J., & Fifer, W. P. (1980). Of human bonding: Newborns prefer their mother’s voices. Science, 208, 1174-1176. DeCasper, A. J., & Spence, M. J. (1986). Prenatal maternal speech influences newborns’ perception of speech sounds. Infant Behavior and Development, 9, 133-150.

Diamond, A. (1985). Development of the ability to use recall to guide actions, as indicated by infants’ performance on AB. Child Development, 56, 868-883.

Dobrich, W., & Scarborough, H. S. (1992). Phonological characteristics of words young children try to say. Journal of Child Language, 19(3), 597–616.

Dubois, J., Hertz-Pannier, L., Cachia, A., Mangin, J. F., Le Bihan, D., & Dehaene-Lambertz, G. (2009). Structural asymmetries in the infant language and sensori-motor networks. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 414–423.

Eisenberg, A., Murkoff, H. E., & Hathaway, S. E. (1989). What to expect the first year. New York: Workman Publishing.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I.K., Murphy, B.C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513-534.

Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, (Serial No. 290, No. 2), 1-160.

El-Dib, M., Massaro, A. N., Glass, P., & Aly, H. (2012). Neurobehavioral assessment as a predictor of neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Journal of Perinatology, 32, 299-303.

Eliot, L. (1999). What’s going on in there? New York: Bantam. Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

Evans, N., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(5), 429–448.

Farroni, T., Johnson, M.H. Menon, E., Zulian, L. Faraguna, D., Csibra, G. (2005). Newborns’ preference for face-relevant stimuli: Effects of contrast polarity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(47), 17245-17250.

Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (1999). Breastfeeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13, 144-157.

Fitzpatrick, E.M., Crawford, L., Ni, A., & Durieux-Smith, A. (2011). A descriptive analysis of language and speech skills in 4-to- 5-yr-old children with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 32(2), 605-616.

Freud, S. (1938). An outline of psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth.

Galler J. R., & Ramsey F. (1989). A follow-up study of the influence of early malnutrition on development: Behavior at home and at school. American Academy of Child and Adolescence Psychiatry, 28 (2), 254-61.

Galler, J. R., Ramsey, F. C., Morely, D. S., Archer, E., & Salt, P. (1990). The long-term effects of early kwashiorkor compared with marasmus. IV. Performance on the national high school entrance examination. Pediatric Research, 28(3), 235- 239.

Galler, J. R., Ramsey, F. C., Salt, P. & Archer, E. (1987). The long-term effect of early kwashiorkor compared with marasmus. III. Fine motor skills. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology Nutrition, 6, 855-859.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37.

Giles, A., & Rovee-Collier, C. (2011). Infant long-term memory for associations formed during mere exposure. Infant Behavior and Development, 34 (2), 327-338.

Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., Baek, J. M., & Chun, D. S. (2008). Genetic correlates of adult attachment style. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1396–1405.

Gleitman, L. R., & Newport, E. L. (1995). The invention of language by children: Environmental and biological influences on the acquisition of language. An Invitation to Cognitive Science, 1, 1-24.

Goldin-Meadow, S., & Mylander, C. (1998). Spontaneous sign systems created by deaf children in two cultures. Nature, 391(6664), 279–281.

Grosse, G., Behne, T., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2010). Infants communicate in order to be understood. Developmental Psychology, 46(6), 1710-1722.

Gunderson, E. P., Hurston, S. R., Ning, X., Lo, J. C., Crites, Y., Walton, D…. & Quesenberry, C. P. Jr. (2015). Lactation and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. American Journal of Medicine, 163, 889-898. Doi: 10.7326/m 15-0807.

Hainline L. (1978). Developmental changes in visual scanning of face and nonface patterns by infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 25, 90–115.

Hamer, R. (2016). The visual world of infants. Scientific American, 104, 98-101. Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673-685.

Harris, Y. R. (2005). Cognitive development. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 276-281). New, York: Sage Publications.

Hart, S., & Carrington, H. (2002). Jealousy in 6-month-old infants. Infancy, 3(3), 395-402.

Hatch, E. M. (1983). Psycholinguistics: A second language perspective. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers. Hertenstein, M. J., & Campos, J. J. (2004). The retention effects of an adult’s emotional displays on infant behavior. Child Development, 75(2), 595–613.

Holland, D., Chang, L., Ernst, T., Curan, M Dale, A. (2014). Structural growth trajectories and rates of change in the first 3 months of infant brain development. JAMA Neurology, 71(10), 1266-1274.

Huttenlocher, P. R., & Dabholkar, A. S. (1997). Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 387(2), 167-178.

Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2004). Children’s temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers’ work functioning. Child Development, 75, 580–594.

Hyvärinen, L., Walthes, R., Jacob, N., Nottingham Chaplin, K., & Leonhardt, M. (2014). Current understanding of what infants see. Current Opthalmological Report, 2, 142-149. doi:10.1007/s40135-014-0056-2

Imai, M., Li, L., Haryu, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Shigematsu, J. (2008). Novel noun and verb learning in Chinese, English, and Japanese children: Universality and language-specificity in novel noun and verb learning. Child Development, 79, 979-1000.

Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G…Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26, 2398-2407.

Iverson, J. M., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2005). Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological science, 16(5), 367-371.

Jarrett, C. (2015). Great myths of the brain. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Johnson, M. H., & deHaan, M. (2015). Developmental cognitive neuroscience: An introduction. Chichester, West Sussex: UK, Wiley & Sons

Jusczyk, P.W., Cutler, A., & Redanz, N.J. (1993). Infants’ preference for the predominant stress patterns of English words. Child Development, 64, 675–687.

Karlson, E.W., Mandl, L.A., Hankison, S. E., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis & Rheumatism, 50 (11), 3458-3467.

Kasprian, G., Langs, G., Brugger, P. C., Bittner, M., Weber, M., Arantes, M., & Prayer, D. (2011). The prenatal origin of hemispheric asymmetry: an in utero neuroimaging study. Cerebral Cortex, 21, 1076–1083.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 251–301. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4

Klein, P. J., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1999). Long-term memory, forgetting, and deferred imitation in 12-month-old infants. Developmental Science, 2(1), 102-113.

Klinnert, M. D., Campos, J. J., & Sorce, J. F. (1983). Emotions as behavior regulators: Social referencing in infancy. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, research, and experience (pp. 57–86). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Kolb, B., & Fantie, B. (1989). Development of the child’s brain and behavior. In C. R. Reynolds & E. Fletcher-Janzen (Eds.),

Handbook of clinical child neuropsychology (pp. 17–39). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Kolb, B. & Whishaw, I. Q. (2011). An introduction to brain and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

Kopp, C. B. (2011). Development in the early years: Socialization, motor development, and consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 165-187.

Latham, M. C. (1997). Human nutrition in the developing world. Rome, IT: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Lavelli, M., & Fogel, A. (2005). Developmental changes in the relationships between infant attention and emotion during early face-to-face communications: The 2 month transition. Developmental Psychology, 41, 265-280.

Lenneberg, E. (1967). Biological foundations of language. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

LeVine, R. A., Dixon, S., LeVine, S., Richman, A., Leiderman, P. H., Keefer, C. H., & Brazelton, T. B. (1994). Child care and culture: Lessons from Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, M., & Brooks, J. (1978). Self-knowledge and emotional development. In M. Lewis & L. A. Rosenblum (Eds.), Genesis of behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 205-226). New York: Plenum Press.

Lewis, T. L., Maurer, D., & Milewski, A. (1979). The development of nasal detection in young infants. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science Supplement, 19, 271.

Li, Y., & Ding, Y. (2017). Human visual development. In Y. Liu., & W. Chen (Eds.), Pediatric lens diseases (pp. 11-20). Singapore: Springer.

Los Angles County Department of Public Health. (2019). Breastfeeding vs. formula feeding. Retrieved from publichealth.lacounty.gov/LAmoms/lessons/Breastfeeding/6_BreastfeedingvsFormulaFeeding.pdf

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment inthe Preschool Years (pp.121– 160).Chicago,IL: UniversityofChicagoPress.

Mandel, D. R., Jusczyk, P. W., & Pisoni, D. B. (1995). Infants’ recognition of the sound patterns of their own names. Psychological Science, 6(5), 314–317.

Mayberry, R. I., Lock, E., & Kazmi, H. (2002). Development: Linguistic ability and early language exposure. Nature, 417(6884), 38.

Moeller, M.P., & Tomblin, J.B. (2015). An introduction to the outcomes of children with hearing loss study. Ear and Hearing, 36 Suppl (0-1), 4S-13S

Morelli, G., Rogoff, B., Oppenheim, D., & Goldsmith, D. (1992). Cultural variations in infants’ sleeping arrangements: Questions of independence. Developmental Psychology, 28, 604-613.

Nelson, E. A., Schiefenhoevel, W., & Haimerl, F. (2000). Child care practices in nonindustrialized societies. Pediatrics, 105, e75.

O’Connor, T. G., Marvin, R. S., Rotter, M., Olrich, J. T., Britner, P. A., & The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. (2003). Child-parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 19- 38.

Papousek, M. (2007). Communication in early infancy: An arena of intersubjective learning. Infant Behavior and Development, 30, 258-266.

Pearson Education. (2016). Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Third Edition. New York: Pearson. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonclinical.com/childhood/products/100000123/bayley-scales-of-infant-and-toddler-development- third-edition-bayley-iii.html#tab-details

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Petitto, L. A., & Marentette, P. F. (1991). Babbling in the manual mode: Evidence for the ontogeny of language. Science, 251(5000), 1493–1496.

Phelps, B. J. (2005). Habituation. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 597-600). New York: Sage Publications.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

Pickens, J., Field, T., Nawrocki, T., Martinez, A., Soutullo, D., & Gonzalez, J. (1994). Full-term and preterm infants’ perception of face-voice synchrony. Infant Behavior and Development, 17(4), 447-455.

Porter, R. H., Makin, J. W., Davis, L. M., Christensen, K. (1992). Responsiveness of infants to olfactory cues from lactating females. Infant Behavior and Development, 15, 85-93.

Redondo, C. M., Gago-Dominguez, M., Ponte, S. M., Castelo, M. E., Jiang, X., Garcia, A.A… Castelao, J. E. (2012). Breast feeding, parity and breast cancer subtypes in a Spanish cohort. PLoS One, 7(7): e40543 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.00040543

Richardson, B. D. (1980). Malnutrition and nutritional anthropometry. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 26(3), 80-84. Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99-116). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., Posner, M. I. & Kieras, J. (2006). Temperament, attention, and the development of self-regulation. In M. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.) Blackwell handbook of early childhood development (pp. 3338-357). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2010). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55, 1093-1104.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1987). Learning and memory in infancy. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development, (2nd, ed., pp. 98-148). New York: Wiley.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1990). The “memory system” of prelinguistic infants. Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 608, 517-542. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-66231990.tb48908.

Rovee-Collier, C., & Hayne, H. (1987). Reactivation of infant memory: Implications for cognitive development. In H. W. Reese (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior. (Vol. 20, pp. 185-238). London, UK: Academic Press.

Rymer, R. (1993). Genie: A scientific tragedy. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Salkind, N. J. (2005). Encyclopedia of human development. New York: Sage Publications.

Schwarz, E. B., Brown, J. S., Creasman, J. M. Stuebe, A., McClure, C. K., Van Den Eeden, S. K., & Thom, D. (2010). Lactation and maternal risk of type-2 diabetes: A population-based study. American Journal of Medicine, 123, 863.e1-863.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.016.

Seifer, R., Schiller, M., Sameroff, A., Resnick, S., & Riordan, K. (1996). Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Developmental Psychology, 32, 12-25.

Sen, M. G., Yonas, A., & Knill, D. C. (2001). Development of infants’ sensitivity to surface contour information for spatial layout. Perception, 30, 167-176.

Senghas, R. J., Senghas, A., & Pyers, J. E. (2005). The emergence of Nicaraguan Sign Language: Questions of development, acquisition, and evolution. In S. T. Parker, J. Langer, & C. Milbrath (Eds.), Biology and knowledge revisited: From neurogenesis to psychogenesis (pp. 287–306). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Shaffer, D. R. (1985). Developmental psychology: Theory, research, and applications. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Inc. Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. NY: Free Press.

Sorce, J. F., Emde, J. J., Campos, J. J., & Klinnert, M. D. (1985). Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds. Developmental Psychology, 21, 195–200.

Spelke, E. S., & Cortelyou, A. (1981). Perceptual aspects of social knowing: Looking and listening in infancy. Infant social cognition, 61-84.

Springer, S. P. & Deutsch, G. (1993). Left brain, right brain (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman.

Stika, C.J., Eisenberg, L.S., Johnson, K.C. Henning, S.C., Colson, B.G., Ganguly, D.H., & DesJardin, J.L. (2015). Developmental outcomes of early-identified children who are hard of hearing at 12 to 18 months of age. Early Human Development, 9(1), 47-55.

Stork, F. & Widdowson, J. (1974). Learning about Linguistics. London: Hutchinson.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth.

Thompson, R. A. (2006). The development of the person. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th Ed.). New York: Wiley.

Thompson, R. A., & Goodvin, R. (2007). Taming the tempest in the teapot. In C. A. Brownell & C. B. Kopp (Eds.). Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations (pp. 320-342). New York: Guilford.

Thompson, R. A., Winer, A. C., & Goodvin, R. (2010). The individual child: Temperament, emotion, self, and personality. In M. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (6th ed., pp. 423–464). New York, NY: Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis.

Titus-Ernstoff, L., Rees, J. R., Terry, K. L., & Cramer, D. W. (2010). Breast-feeding the last-born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control, 21(2), 201-207. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9450-8

Tomblin, J. B., Harrison, M., Ambrose, S. E., Walker, E. A., Oleson, J. J., & Moeller, M. P. (2015). Language outcomes in young children with mild to severe hearing loss. Ear and hearing, 36 Suppl 1(0 1), 76S–91S.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2015). Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2015. United Nations Children’s Fund. New York: NY.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health. (2011). Your guide to breast feeding. Washington D.C.

United States National Library of Medicine. (2016). Circumcision. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/circumcision.html

Van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development, 65, 1457–1477.

Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi, A. (1999). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 713-734). New York: Guilford.

Webb, S. J., Monk, C. S., & Nelson, C. A. (2001). Mechanisms of postnatal neurobiological development: Implications for human development. Developmental Neuropsychology, 19, 147-171.

Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. & Shackelford, T. K. (2005). Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 1238-1239). New York: Sage Publications.

Werker, J. F., Pegg, J. E., & McLeod, P. J. (1994). A cross-language investigation of infant preference for infant-directed communication. Infant Behavior and Development, 17, 323-333.

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (2002). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 25, 121-133.

Attribution

Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective Second Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 unported license.