11.1: Chapter 25- Physical Development in Middle Adulthood

- Page ID

- 55314

Chapter 25 Learning Objectives

- Explain the difference between primary and secondary aging

- Describe sensory changes that occur during middle adulthood

- Identify health concerns in middle adulthood

- Explain what occurs during the climacteric for females and males

- Describe sexuality during middle adulthood

- Explain the importance of sleep and consequences of sleep deprivation

- Describe the importance of exercise and nutrition for optimal health

- Describe brain functioning in middle adulthood

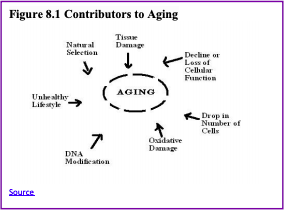

biological factors, such as molecular and cellular changes, and oxidative damage are called primary aging, while aging that occurs due to controllable factors, such as an unhealthy lifestyle including lack of physical exercise and poor diet, is called secondary aging (Busse, 1969). These factors are shown in Figure 8.1

Physical Changes

Hair: When asked to imagine someone in middle adulthood, we often picture someone with the beginnings of wrinkles and gray or thinning hair. What accounts for these physical changes?

Skin: Skin continues to dry out and is prone to more wrinkling, particularly on the sensitive face area. Wrinkles, or creases in the skin, are a normal part of aging. As we get older, our skin dries and loses the underlying layer of fat, so our face no longer appears smooth. Loss of muscle tone and thinning skin can make the face appear flabby or drooping. Although wrinkles are a natural part of aging and genetics plays a role, frequent sun exposure and smoking will cause wrinkles to appear sooner. Dark spots and blotchy skin also occur as one ages and are due to exposure to sunlight (Moskowitz, 2014). Blood vessels become more apparent as the skin continues to dry and get thinner.

Sarcopenia: The loss of muscle mass and strength that occurs with aging is referred to as sarcopenia (Morley, Baumgartner, Roubenoff, Mayer, & Nair, 2001). Sarcopenia is thought to be a significant factor in the frailty and functional impairment that occurs when older. The decline of growth and anabolic hormones, especially testosterone, and decreased physical activity have been implicated as causes of sarcopenia (Proctor, Balagopal, & Nair, 1998). This decline in muscle mass can occur as early as 40 years of age and contributes significantly to a decrease in life quality, increase in health care costs, and early death in older adults (Karakelides & Nair, 2005). Exercise is certainly important to increase strength, aerobic capacity, and muscle protein synthesis, but unfortunately it does not reverse all the age-related changes that occur. The muscle-to-fat ratio for both men and women also changes throughout middle adulthood, with an accumulation of fat in the stomach area.

Lungs: The lungs serve two functions: Supply oxygen and remove carbon dioxide. Thinning of the bones with age can change the shape of the rib cage and result in a loss of lung expansion. Age-related changes in muscles, such as the weakening of the diaphragm, can also reduce lung capacity. Both of these changes will lower oxygen levels in the blood and increase the levels of carbon dioxide. Experiencing shortness of breath and feeling tired can result (NIH, 2014b). In middle adulthood, these changes and their effects are often minimal, especially in people who are non-smokers and physically active. However, in those with chronic bronchitis, or who have experienced frequent pneumonia, asthma other lung-related disorders, or who are smokers, the effects of these normal age changes can be more pronounced.

Sensory Changes

Vision: A normal change of the eye due to age is presbyopia, which is Latin for “old vision.” It refers to a loss of elasticity in the lens of the eye that makes it harder for the eye to focus on objects that are closer to the person. When we look at something far away, the lens flattens out; when looking at nearby objects tiny muscle fibers around the lens enable the eye to bend the lens. With age these muscles weaken and can no longer accommodate the lens to focus the light. Anyone over the age of 35 is at risk for developing presbyopia. According to the National Eye Institute (NEI) (2016), signs that someone may have presbyopia include:

- Hard time reading small print

- Having to hold reading material farther than arm’s distance

- Problems seeing objects that are close

- Headaches

- Eyestrain

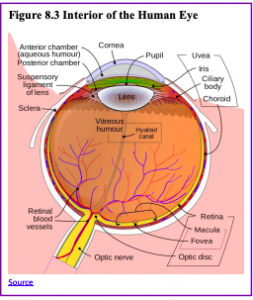

floaters, little spots or “cobwebs” that float around the field of vision. They are most noticeable if you are looking at the sky on a sunny day, or at a lighted blank screen. Floaters occur when the vitreous, a gel-like substance in the interior of the eye, slowly shrinks. As it shrinks, it becomes somewhat stringy, and these strands can cast tiny shadows on the retina. In most cases, floaters are harmless, more of an annoyance than a sign of eye problems. However, floaters that appear suddenly, or that darken and obscure vision can be a sign of more serious eye problems, such a retinal tearing, infection, or inflammation. People who are very nearsighted (myopic), have diabetes, or who have had cataract surgery are also more likely to have floaters (NEI, 2009).

scotopic sensitivity, the ability to see in dimmer light. By age 60, the retina receives only one third as much light as it did at age 20, making working in dimmer light more difficult (Jackson & Owsley, 2000). Night vision is also affected as the pupil loses some of its ability to open and close to accommodate drastic changes in light. Eyes become more sensitive to glare from headlights and street lights making it difficult to see people and cars, and movements outside of our direct line of sight (NIH, 2016c).

dry eye syndrome, which occurs when the eye does not produce tears properly, or when the tears evaporate too quickly because they are not the correct consistency (NEI, 2013). While dry eye can affect people at any age, nearly 5 million Americans over the age of 50 experience dry eye. It affects women more than men, especially after menopause. Women who experienced an early menopause may be more likely to experience dry eye, which can cause surface damage to the eye.

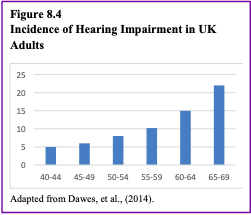

Hearing: Hearing problems increase during middle adulthood. According to a recent UK study (Dawes et al., 2014), the rate of hearing problems in their sample doubled between the ages of 40 and 55 and tripled by age 64. Similar statistics are found in U.S. samples of middle-aged adults. Prior to age 40, about 5.5% of adults report hearing problems. This jumps to 19% among 40 to 69 year-olds (American Psychological Association, 2016). Middle-aged adults may experience more problems understanding speech when in noisy environments, in comparison to younger adults (Füllgrabe, Moore, & Stone, 2015; Neidleman, Wambacq, Besing, Spitzer, & Koehnke, 2015). As we age we also lose the ability to hear higher frequencies (Humes, Kewley-Port, Fogerty, & Kinney, 2010). Hearing changes are more common among men than women, but males may underestimate their hearing problems (Uchida, Nakashima, Ando, Niino, & Shimokata, 2003). For many adults, hearing loss accumulates after years of being exposed to intense noise levels. Men are more likely to work in noisy occupations. Hearing loss is also exacerbated by cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, and stroke. Most hearing loss could be prevented by guarding against being exposed to extremely noisy environments.

Health Concerns

Heart Disease: According to the most recent National Vital Statistics Reports (Kochanek, Murphy, Xu, & Arias, 2019) heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death for Americans as it claimed 23% of those who died in 2017. It is also the number one cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2018). Heart disease develops slowly over time and typically appears in midlife (Hooker & Pressman, 2016).

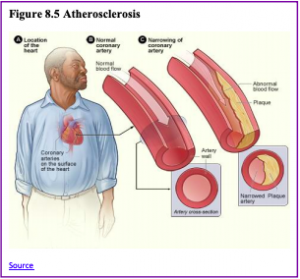

Atherosclerosis, or a buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries, is the most common cause of cardiovascular disease. The plaque buildup thickens the artery walls and restricts the blood flow to organs and tissues. Cardiovascular disease can lead to a heart attack, chest pain (angina), or stroke (Mayo Clinic, 2014a). Figure 8.5 illustrates atherosclerosis.

- Advanced Age-increased risk for narrowed arteries and weakened or thickened heart muscle.

- Sex-males are at greater risk, but a female’s risk increases after menopause.

- Family History-increased risk, especially if male parent or brother developed heart. disease before age 55 or female parent or sister developed heart disease before age 65.

- Smoking-nicotine constricts blood vessels and carbon monoxide damages the inner lining.

- Poor Diet-a diet high in fat, salt, sugar, and cholesterol.

- Excessive Alcohol Consumption-alcohol can raise the level of bad fats in the blood and increase blood pressure

- Stress-unrelieved stress can damage arteries and worsen other risk factors.

- Poor Hygiene-establishing good hygiene habits can prevent viral or bacterial infections that can affect the heart. Poor dental care can also contribute to heart disease.

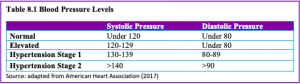

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a serious health problem that occurs when the blood flows with a greater force than normal. One in three American adults (70 million people) have hypertension and only half have it under control (Nwankwo, Yoon, Burt, & Gu, 2013). It can strain the heart, increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, or damage the kidneys (CDC, 2014a). Uncontrolled high blood pressure in early and middle adulthood can also damage the brain’s white matter (axons) and may be linked to cognitive problems later in life (Maillard et al., 2012). Normal blood pressure is under 120/80 (see Table 8.1). The first number is the systolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heartbeats. The second number is the diastolic pressure, which is the pressure in the blood vessels when the heart is at rest. High blood pressure is sometimes referred to as the silent killer, as most people with hypertension experience no symptoms. Making positive lifestyle changes can often reduce blood pressure.

- Family history of hypertension

- A diet that is too high in sodium often found in processed foods, and too low in potassium

- Sedentary lifestyle and Obesity

- Too much alcohol consumption

- Tobacco use, as nicotine raises blood pressure (CDC, 2014b)

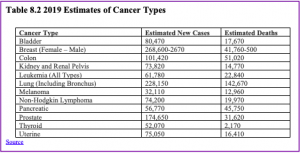

Cancer: After heart disease, cancer was the second leading cause of death for Americans in 2017 as it accounted for 21.3% of all deaths (Kochanek et al., 2016). According to the National Institutes of Health (2015), cancer is the name given to a collection of related diseases in which the body’s cells begin to divide without stopping and spread into surrounding tissues. These extra cells can divide, and form growths called tumors, which are typically masses of tissue. Cancerous tumors are malignant, which means they can invade nearby tissues. When removed malignant tumors may grow back. Unlike malignant tumors, benign tumors do not invade nearby tissues. Benign tumors can sometimes be quite large, and when removed usually do not grow back. Although benign tumors in the body are not cancerous, benign brain tumors can be life-threatening.

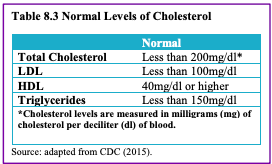

Cholesterol is a waxy fatty substance carried by lipoprotein molecules in the blood. It is created by the body to create hormones and digest fatty foods and is also found in many foods. Your body needs cholesterol, but too much can cause heart disease and stroke. Two important kinds of cholesterol are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The third type of fat is called triglycerides. Your total cholesterol score is based on all three types of lipids (see Table 8.3). Total cholesterol is calculated by adding HDL plus LDL plus 20% of the Triglycerides.

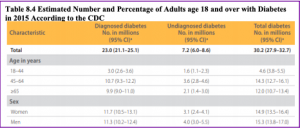

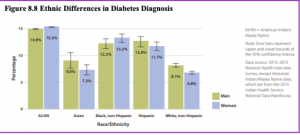

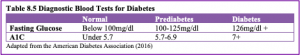

Diabetes (Diabetes Mellitus) is a disease in which the body does not control the amount of glucose in the blood. This disease occurs when the body does not make enough insulin or does not use it the way it should (NIH, 2016a). Insulin is a type of hormone that helps glucose in the blood enter cells to give them energy. In adults, 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes are type 2 (American Diabetes Association (ADA), 2016). Type 2 diabetes usually begins with insulin resistance, a disorder in which the cells in the muscles, liver, and fat tissue do not use insulin properly (CDC, 2014d). As the need for insulin increases, cells in the pancreas gradually lose the ability to produce enough insulin. In some Type 2 diabetics, pancreatic beta cells will cease functioning, and the need for insulin injections will become necessary. Some people with diabetes experience insulin resistance with only minor dysfunction of the beta-cell secretion of insulin. Other diabetics experience only slight insulin resistance, with the primary cause being a lack of insulin secretion (CDC, 2014d).

- Those over age 45

- Obesity

- Family history of diabetes

- History of gestational diabetes (see Chapter 2)

- Race and ethnicity

- Physical inactivity

- Diet.

diabetic retinopathy, which is damage to the small blood vessels in the retina that may lead to loss of vision (NEI, 2015). More than 4% showed advanced diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes is linked as the primary cause of almost half (44%) of new cases of kidney failure each year. About 60% of non-traumatic limb amputations occur in people with diabetes. Diabetes has been linked to hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), gum disease, and neuropathy (nerve disease) (CDC, 2014d).

Metabolic Syndrome is a cluster of several cardiometabolic risk factors, including large waist circumference, high blood pressure, and elevated triglycerides, LDL, and blood glucose levels, which can lead to diabetes and heart disease (Crist et al., 2012). The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the U.S. is approximately 34% and is especially high among Hispanics and African Americans (Ford, Li, & Zhao, 2010). Prevalence increases with age, peaking in one’s 60s (Ford et al., 2010). Metabolic syndrome increases morbidity from cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Hu et al., 2004; Malik, 2004). Hu and colleagues found that even having one or two of the risk factors for metabolic syndrome increased the risk of mortality. Crist et al. (2012) found that increasing aerobic activity and reducing weight led to a drop in many of the risk factors of metabolic syndrome, including a reduction in waist circumference and blood pressure, and an increase in HDL cholesterol.

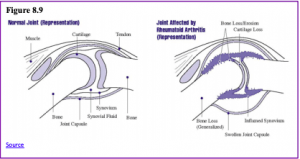

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory disease that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in the joints (NIH, 2016b). RA occurs when the immune system attacks the membrane lining the joints (see Figure 8.8). RA is the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis, which is the normal wear and tear on the joints discussed in chapter 9. Unlike osteoarthritis, RA is symmetric in its attack of the body, thus, if one shoulder is affected so is the other. In addition, those with RA may experience fatigue and fever. Below are the common features of RA (NIH, 2016b).

Features of Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- Symmetrical pattern of affected joints

- Joint inflammation often affecting the wrist and finger joints closest to the hand

- Joint inflammation sometimes affecting other joints, including the neck, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles, and feet

- Fatigue, occasional fevers, a loss of energy

- Pain and stiffness lasting for more than 30 minutes in the morning or after a long rest

- Symptoms that last for many years

- Variability of symptoms among people with the disease.

Fatty liver disease (hepatic steatosis) refers to the accumulation of fat in the liver. The liver normally contains little fat, and anything below 5% of liver weight is considered normal. This disease is present in 33% of American adults. In the past, the main cause of fat accumulation in the liver was due to excessive alcohol consumption, often eventually leading to cirrhosis and liver failure. Today, increased caloric intake, especially resulting in obesity, and little physical activity are the main causes. Mild to moderate levels of hepatic steatosis can be reversed through healthy lifestyle changes (Nassir, Rector, Hammoud, & Ibdah, 2015).

Digestive Issues

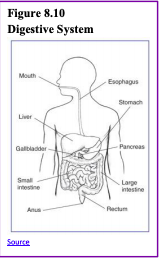

Heartburn, also called acid indigestion or pyrosis, is a common digestive problem in adults and is the result of stomach acid backing up into the esophagus. Prolonged contact with the digestive juices injures the lining of the esophagus and causes discomfort. Heartburn that occurs more frequently may be due to gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD. Normally the lower sphincter muscle in the esophagus keeps the acid in the stomach from entering the esophagus. In GERD this muscle relaxes too frequently and the stomach acid flows into the esophagus. In the U.S., 60 million people experience heartburn at least once a month, and 15 million experience it every day. Prolonged problems with heartburn can lead to more serious complications, including esophageal cancer, one of the most lethal forms of cancer in the U.S. Problems with heartburn can be linked to eating fatty or spicy foods, caffeine, smoking, and eating before bedtime (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016a).

Gallstones are hard particles, including fatty materials, bile pigments, and calcium deposits, that can develop in the gallbladder. Ranging in size from a grain of sand to a golf ball, they typically take years to develop, but in some people have developed over the course of a few months. About 75% of gallstones do not create any symptoms, but those that do may cause sporadic upper abdominal pain when stones block bile or pancreatic ducts. If stones become lodged in the ducts, it may necessitate surgery or other medical intervention as it could become life-threatening if left untreated (American College of Gastroenterology, 2016b).

Sleep

Sleep problems: According to the Sleep in America poll (National Sleep Foundation, 2015), 9% of Americans report being diagnosed with a sleep disorder, and of those 71% have sleep apnea and 24% suffer from insomnia. Pain is also a contributing factor in the difference between the amount of sleep Americans say they need and the amount they are getting. An average of 42 minutes of sleep debt occur for those with chronic pain, and 14 minutes for those who have suffered from acute pain in the past week. Stress and overall poor health are also key components of shorter sleep durations and worse sleep quality. Those in midlife with lower life satisfaction experienced greater delay in the onset of sleep than those with higher life satisfaction. Delayed onset of sleep could be the result of worry and anxiety during midlife, and improvements in those areas should improve sleep. Lastly, menopause can affect a woman’s sleep duration and quality (National Sleep Foundation, 2016).

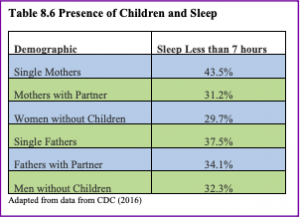

Children in the home and sleep: As expected, having children at home affects the amount of sleep one receives. According to a 2016 National Center for Health Statistics analysis (CDC, 2016) having children decreases the amount of sleep an individual receives, however, having a partner can improve the amount of sleep for both males and females. Table 8.6 illustrates the percentage of individuals not receiving seven hours of sleep per night based on parental role.

Negative consequences of insufficient sleep: There are many consequences of too little sleep, and they include physical, cognitive, and emotional changes. Sleep deprivation suppresses immune responses that fight off infection, and can lead to obesity, memory impairment, and hypertension (Ferrie et al., 2007; Kushida, 2005). Insufficient sleep is linked to an increased risk for colon cancer, breast cancer, heart disease and type 2 diabetes (Pattison, 2015). A lack of sleep can increase stress as cortisol (a stress hormone) remains elevated which keeps the body in a state of alertness and hyperarousal which increases blood pressure. Sleep is also associated with longevity. Dew et al. (2003) found that older adults who had better sleep patterns also lived longer. During deep sleep a growth hormone is released which stimulates protein synthesis, breaks down fat that supplies energy, and stimulates cell division. Consequently, a decrease in deep sleep contributes to less growth hormone being released and subsequent physical decline seen in aging (Pattison, 2015).

Exercise, Nutrition, and Weight

The impact of exercise: Exercise is a powerful way to combat the changes we associate with aging. Exercise builds muscle, increases metabolism, helps control blood sugar, increases bone density, and relieves stress. Unfortunately, fewer than half of midlife adults exercise and only about 20 percent exercise frequently and strenuously enough to achieve health benefits. Many stop exercising soon after they begin an exercise program, particularly those who are very overweight. The best exercise programs are those that are engaged in regularly, regardless of the activity. A well-rounded program that is easy to follow includes walking and weight training. Having a safe, enjoyable place to walk can make the difference in whether or not someone walks regularly. Weight lifting and stretching exercises at home can also be part of an effective program. Exercise is particularly helpful in reducing stress in midlife. Walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming can release the tension caused by stressors. Learning relaxation techniques can also have healthful benefits. Exercise can be thought of as preventative health care. Promoting exercise for the 78 million “baby boomers” may be one of the best ways to reduce health care costs and improve quality of life (Shure & Cahan, 1998).

- Adults should avoid being inactive. Any activity will result in some health benefits.

- For substantial health benefits, adults should engage in at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise OR at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity. Aerobic activity should occur for at least 10 minutes and preferably spread throughout the week.

- For more extensive health benefits, adults can increase their aerobic activity to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity OR 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity.

- Adults should also participate in muscle-strengthening activities that are moderate or high intensity and involve all major muscle groups on two or more days per week.

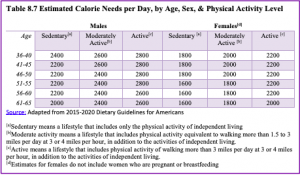

Nutritional concerns: Aging brings about a reduction in the number of calories a person requires (see Table 8.7 for estimated caloric needs in middle-aged adults). Many Americans respond to weight gain by dieting. However, eating less does not typically mean eating right and people often suffer vitamin and mineral deficiencies as a result. All adults need to be especially cognizant of the amount of sodium, sugar, and fat they are ingesting.

Excess Sodium: According to dietary guidelines, adults should consume less than 2,300mg (1 teaspoon) per day of sodium. The American Heart Association (2016) reports that the average sodium intake among Americans is 3440mg per day. Processed foods are the main culprits of excess sodium. High sodium levels in the diet is correlated with increased blood pressure, and its reduction does show corresponding drops in blood pressure. Adults with high blood pressure are strongly encouraged to reduce their sodium intake to 1500mg (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture (USHHS & USDA), 2015).

Excess Fat: Dietary guidelines also suggests that adults should consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from saturated fats. The American Heart Association (2016) says optimally we should aim for a dietary pattern that achieves 5% to 6% of calories from saturated fat. In a 2000 calorie diet that is about 120 calories from saturated fat. In the average American diet about 34.3% of the diet comes from fat, with 15.0% from saturated fat (Berglund et al., 1999). Diets high in fat not only contribute to weight gain, but have been linked to heart disease, stroke, and high cholesterol.

Added Sugar: According to the recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans (USHHS & USDA, 2015) eating healthy means adults should consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from added sugars. Yet, currently, about 15% of the calories in the American adult diet come from added sugars, or about 22 teaspoons of sugar per day (NIH, 2014c). Excess sugar not only contributes to weight gain but diabetes and other health problems.

Metabolism and Weight Gain: One of the common complaints of midlife adults is weight gain, especially the accumulation of fat in the abdomen, which is often referred to as the middle-aged spread (Lachman, 2004). Men tend to gain fat on their upper abdomen and back, while women tend to gain more fat on their waist and upper arms. Many adults are surprised at this weight gain because their diets have not changed, however, their metabolism has slowed during midlife. Metabolism is the process by which the body converts food and drink into energy. The calories consumed are combined with oxygen to release the energy needed to function (Mayo Clinic, 2014b). People who have more muscle burn more calories, even at rest, and thus have a higher metabolism.

Obesity: As discussed in the early adulthood chapter, obesity is a significant health concern for adults throughout the world, and especially America. Obesity rates continue to increase and the current rate for those 40-59 is 42.8%, which is the highest percentage per age group (CDC, 2017). Being overweight is associated with a myriad of health conditions including diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. New research is now linking obesity to Alzheimer’s disease. Chang et al. (2016) found that being overweight in midlife was associated with earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease. The study looked at 1,394 men and women who were part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Their average age was around 60, and they were followed for 14 years. Results indicated that people with the highest body mass index, or BMI, at age 50 were more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, each one-point increase in BMI was associated with getting Alzheimer’s six to seven months earlier. Those with the highest BMIs also had more brain changes typical of Alzheimer’s, even if they did not have symptoms of the disease. Scientists speculate that fat cells may produce harmful chemicals that promote inflammation in blood vessels throughout the body, including in the brain. The conclusion of the study was that a healthy BMI at midlife may delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Concluding Thoughts: Many of the changes that occur in midlife can be easily compensated for, such as buying glasses, exercising, and watching what one eats. However, the percentage of middle adults who have a significant health concern has increased in the past 15 years. According to the 2016 United Health Foundation’s America’s Health Rankings Senior Report, the next generation of seniors will be less healthy than the current seniors (United Health Foundation, 2016). The study compared the health of middle-aged Americans (50-64 years of age) in 2014 to middle-aged Americans in 1999. Results indicated that in the past 15 years the prevalence of diabetes has increased by 55% and the prevalence of obesity has increased by 25%. At the state level, Massachusetts ranked first for healthy seniors, while Louisiana ranked last. Illinois ranked 36th, while Wisconsin scored higher at 13th.

Climacteric

climacteric, or the midlife transition when fertility declines, is biologically based but impacted by the environment. During midlife, men may experience a reduction in their ability to reproduce. Women, however, lose their ability to reproduce once they reach menopause.

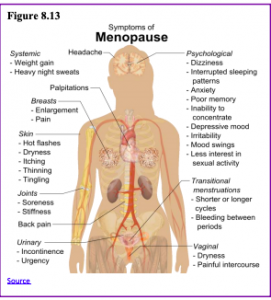

Female Sexual and Reproductive Health: Perimenopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases. Menopause is defined as 12 months without menstruation. The average age of menopause is approximately 51, however, many women begin experiencing symptoms in their 40s. These symptoms occur during perimenopause, which can occur 2 to 8 years before menopause (Huang, 2007). A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction.

Symptoms: The symptoms that occur during perimenopause and menopause are typically caused by the decreased production of estrogen and progesterone (North American Menopause Society, 2016). The shifting hormones can contribute to the inability to fall asleep. Additionally, the declining levels of estrogen may make a woman more susceptible to environmental factors and stressors which disrupt sleep. A hot flash is a surge of adrenaline that can awaken the brain from sleep. It often produces sweat and a change of temperature that can be disruptive to sleep and comfort levels. Unfortunately, it may take time for the adrenaline to recede and allow sleep to occur again (National Sleep Foundation, 2016).

to change their lifestyle to counter any weight gain. Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women who have prior histories of these conditions rather than those who have not.

Hormone Replacement Therapy: Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement has changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. However, more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NIH,

Menopause and Ethnicity: In a review of studies that mentioned menopause, symptoms varied greatly across countries, geographic regions, and even across ethnic groups within the same region (Palacios, Henderson, & Siseles, 2010). For example, the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) examined 14,906 white, African American, Hispanic, Japanese American, and Chinese American women’s menopausal experiences (Avis et al., 2001). After controlling for age, educational level, general health status, and economic stressors, white women were more likely to disclose symptoms of depression, irritability, forgetfulness, and headaches compared to women in the other racial/ethnic groups. African American women experienced more night sweats, but this varied across research sites. Finally, Chinese American and Japanese American reported fewer menopausal symptoms when compared to the women in the other groups. Overall, the Chinese and Japanese groups reported the fewest symptoms, while white women reported more mental health symptoms and African American women reported more physical symptoms.

Cultural Differences: Cultural influences seem to also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. Further, the prevalence of language specific to menopause is an important indicator of the occurrence of menopausal symptoms in a culture. Hmong tribal women living in Australia and Mayan women report that there is no word for “hot flashes” and both groups did not experience these symptoms (Yick-Flanagan, 2013). When asked about physical changes during menopause, the Hmong women reported lighter or no periods. They also reported no emotional symptoms and found the concept of emotional difficulties caused by menopause amusing (Thurston & Vissandjee, 2005). Similarly, a study with First Nation women in Canada found there was no single word for “menopause” in the Oji-Cree or Ojibway languages, with women referring to menopause only as “that time when periods stop” (Madden, St Pierre-Hansen & Kelly, 2010).

Male Sexual and Reproductive Health: Although males can continue to father children throughout middle adulthood, erectile dysfunction (ED) becomes more common. Erectile dysfunction refers to the inability to achieve an erection or an inconsistent ability to achieve an erection (Swierzewski, 2015). Intermittent ED affects as many as 50% of men between the ages of 40 and 70. About 30 million men in the United States experience chronic ED and the percentages increase with age. Approximately 4% of men in their 40s, 17% of men in their 60s, and 47% of men older than 75 experience chronic ED.

If testosterone levels decline significantly, it is referred to as andropause or late-onset hypogonadism. Identifying whether testosterone levels are low is difficult because individual blood levels vary greatly. Low testosterone is not a concern unless it accompanied by negative symptoms such as low sex drive, ED, fatigue, loss of muscle, loss of body hair, or breast enlargement. Low testosterone is also associated with medical conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, and testicular cancer. The effectiveness of supplemental testosterone is mixed, and long term testosterone replacement therapy for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer, blood clots, heart attack, and stroke (WebMD, 2016). Most men with low testosterone do not have related problems (Berkeley Wellness, 2011).

The Climacteric and Sexuality

Brain Functioning

References

AARP. (2009). The divorce experience: A study of divorce at midlife and beyond. Washington, DC: AARP

Ahlborg, T., Misvaer, N., & Möller, A. (2009). Perception of marital quality by parents with small children: A follow-up study when the firstborn is 4 years old. Journal of Family Nursing, 15, 237–263.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2013). Relationship goals of middle-aged, young-old, and old-old Internet daters: An analysis of online personal ads. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 159–165. doi.10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.006

American Association of Community Colleges (2016). Plus 50 community colleges: Ageless learning. Retrieved from plus50.aacc.nche.edu/Pages/Default.aspx

American Cancer Society. (2019). Cancer Facts and Figures 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf

American Diabetes Association (2016). Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 39(1), 1-112.

American Heart Association (2016). Saturated fats. Retrieved from www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyEating/Nutrition/Saturated-Fats_UCM_301110_Article.jsp

American Psychological Association (2017). Stress in America: The state of our nation. Retrieved from www.apa.org/images/state-nation_tcm7-225609.pdf

American Psychological Association (2016). By the numbers: Hearing loss and mental health. Monitor on Psychology, 47(4), 9.

Anderson, E. R., & Greene, S. M. (2011). “My child and I are a package deal”: Balancing adult and child concerns in repartnering after divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 741-750.

Anderson, E.R., Greene, S.M., Walker, L., Malerba, C.A., Forgatch, M.S., & DeGarmo, D.S. (2004). Ready to take a chance again: Transitions into dating among divorced parents. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 40, 61-75.

Aquilino, W. (1991). Predicting parents’ experiences with coresidence adult children. Journal of Family Issues, 12(3), 323-342.

Arai, Y., Sugiura, M., Miura, H., Washio, M., & Kudo, K. (2000). Undue concern for other’s opinions deters caregivers of impaired elderly from using public services in rural Japan. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(10), 961- 968.

Armour, S. (2007, August 2). Friendships and work: A good or bad partnership? USA Today. Retrieved from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/2007-08-01-work-friends_N.htm

Avis, N. E., Stellato, R., & Crawford, S. (2001). Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Social Science and Medicine, 52(3), 345-356.

Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan Psychology: Theory and Application to Intellectual Functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471-507.

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A, & Fitsimons, G. G. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the true self on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 33–48.

Barreto, M., Ryan, M. K., & Schmitt, M. T. (2009). The glass ceiling in the 21st century: Understanding the barriers to gender equality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Baruch, G., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1984). Women in midlife. New York: Plenum.

Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Yee, J. L., & Jackson, S. (2000). Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: Longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 259-271.

Beit-Hallahmi, B., & Argyle, M. (1998). Religious behavior, belief, and experience. New York: Routledge.

Bengtson, V. L. (2001). Families, intergenerational relationships, and kinkeeping in midlife. In N. M. Putney (Author) & M. E. Lachman (Ed.), Handbook of midlife development (pp. 528-579). New York: Wiley.

Berglund, L., Oliver, E. H., Fontanez, N., Holleran, S., Matthews, K., Roheim, P. S., & DELTA Investigators. (1999). HDL- subpopulation patterns in response to reductions in dietary total and saturated fat intakes in healthy subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70, 992-1000.

Berkeley Wellness. (2011). The lowdown on low testosterone. Retrieved from http://www.berkeleywellness.com/self-care/sexual-health/article/lowdown-low-testosterone

Besen, E., Matz-Costa, C., Brown, M., Smyer, M. A., & Pitt-Catsouphers, M. (2013). Job characteristics, core self-evaluations, and job satisfaction. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 76(4), 269-295.

Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1981). The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 139–157.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T.C. (2012). Till death do us part: Contexts and implications of marriage, divorce, and remarriage across adulthood. Research in Human Development, 9(2), 103-105.

Borland, D. C. (1982). A cohort analysis approach to the empty-nest syndrome among three ethnic groups of women: A theoretical position. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 117–129.

Borzumato-Gainey, C., Kennedy, A., McCabe, B., & Degges-White, S. (2009). Life satisfaction, self-esteem, and subjective age in women across the life span. Adultspan Journal, 8(1), 29-42.

Bouchard, G. (2013). How do parents reaction when their children leave home: An integrative review. Journal of Adult Development, 21, 69-79.

Bromberger, J. T., Kravitz, H. M., & Chang, Y. (2013). Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause, 20(5), 488-495.

Brown, L. H., & DeRycke, S. B. (2010). The kinkeeping connection: Continuity, crisis and consensus. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 8(4), 338-353, DOI: 10.1080/15350770.2010.520616

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I. (2013). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle aged and older adults 1990-2010. National Center for Family & Marriage Research Working Paper Series. Bowling Green State University. www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and- sciences/NCFMR/ documents/Lin/The-Gray-Divorce.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). The employment situation-June 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

Busse, E. W. (1969). Theories of aging. In E. W. Busse & E/. Pfeiffer (Eds.), Behavior and adaptation in later life (pp. 11-31). Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Carmichael, C. L., Reis, H. T., & Duberstein, P. R. (2015). In your 20s it’s quantity, in your 30s it’s quality: The prognostic value of social activity across 30 years of adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 30(1), 95-105.

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283.

Center for Sexual Health Promotion. (2010). National survey of sexual health and behavior. Retrieved from http://www.sexualhealth.indiana.edu

Centers for Disease Control (2014a). About high blood pressure. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/about.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014b). Behaviors that increase the risk for high blood pressure. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/behavior.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014c). Measuring high blood pressure. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/measure.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014d). National diabetes statistics report, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014e). Diagnoses of HIV infection among adults aged 50 years and older in the United States and dependent areas 2010–2014. HIV surveillance report, 21(2), 1-69. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-21-2.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Facts about high cholesterol. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/facts.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). The National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). National diabetes statistics report, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

Chang, Y. F., An, Y., Bigel, M., Wong, D. F., Troncoso, J. C., O’Brien, R. J., Breitner, J. C., Ferruci, L., Resnick, S. M., & Thanbisetty, M. (2016). Midlife adiposity predicts earlier onset of Alzheimer’s dementia, neuropathology and presymptomatic cerebral amyloid accumulation. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(7), 910-915.

Charness, N., & Krampe, R. T. (2006). Aging and expertise. In K. Ericsson, N. Charness & P. Feltovich (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Cherlin, A. J., & Furstenberg, F. F. (1986). The new American grandparent: A place in the family, a life apart. New York: Basic Books.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Crawford, S. & Channon, S. (2002). Dissociation between performance on abstract tests of executive function and problem solving in real life type situations in normal aging. Aging and Mental Health, 6, 12-21.

Crist, L. A., Champagne, C. M., Corsino, L., Lien, L. F., Zhang, G., & Young, D. R. (2012). Influence of change in aerobic fitness and weight on prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Preventing Chronic Disease 9,110171. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd9.110171

Crowson, C. S., Matteson, E. L., Myasoedova, E., Michet, C. J., Ernste, F. C., Warrington, K. J., …Gabriel, S. E. (2011). The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 63(3), 633-639. doi: 10.1002/art.30155.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper

Collins. Dawes, P., DicMonrokinson, C., Emsley, R., Bishop, P. N., Cruickshanks, K. J., Edmundson-Jones, M., …. Munro, K. (2014). Vision impairment and dual sensory problems in middle age. Ophthalmic Physiological Optics, 34, 479–488. doi: 10.1111/opo.12138479

Degges-White, S., & Myers, J, E. (2006). Women at midlife: An exploration of chronological age, subjective age, wellness, and life satisfaction, Adultspan Journal, 5, 67-80.

DeLongis, A., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 486–495.

Dennerstein, L., Dudley, E., & Guthrie, J. (2002). Empty nest or revolving door? A prospective study of women’s quality of life in midlife during the phase of children leaving and re-entering the home. Psychological Medicine, 32, 545–550.

DePaulo, B. (2014). A singles studies perspective on mount marriage. Psychological Inquiry, 25(1), 64-68. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.878173

Desilver, D. (2016). In the U. S. and abroad, more young adults are living with their parents. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/05/24/in-the-u-s-and-abroad-more-young-adults-are-living-with-their-parents/

de St. Aubin, E., & Mc Adams, D. P. (1995). The relation of generative concern and generative action to personality traits, satisfaction/happiness with life and ego development. Journal of Adult Development, 2, 99-112.

De Vaus, D. & McAllister, I. (1987). Gender differences in religion: A test of the structural location theory. American Sociological Review, 52, 472-481.

Dew, M. A., Hoch, C. C., Buysse, D. J., Monk, T. H., Begley, A. E., Houck, P. R.,…Reynolds, C. F., III. (2003). Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(1), 63–73.

Dimah, K., & Dimah, A. (2004). Intimate relationships and sexual attitudes of older African American men and women. The Gerontologist, 44, 612-613.

Drake, B. (2013). Another gender gap: Men spend more time in leisure activities. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/06/10/another-gender-gap-men-spend-more-time-in-leisure-activities/

Dunér, A., & Nordstrom, M. (2007). The roles and functions of the informal support networks of older people who receive formal support: A Swedish qualitative study. Ageing & Society, 27, 67– 85. doi:10.1017/ S0144686X06005344

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 463-482.

Eastley, R., & Wilcock, G. K. (1997). Prevalence and correlates of aggressive behaviors occurring in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12, 484-487.

Elsesser, L., & Peplau, L. A. (2006). The glass partition: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Human Relations, 59(8), 1077–1100.

Emslie, C., Hunt, K., & Lyons, A. (2013. The role of alcohol in forging and maintaining friendships amongst Scottish men in midlife. Health Psychology, 32(10, 33-41.

Ericsson, K. A., Feltovich, P. J., & Prietula, M. J. (2006). Studies of expertise from psychological perspectives. In K. Ericsson, N. Charness & P. Feltovich (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton & Company. Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton & Company. Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York: Norton & Company.

Fehr, B. (2008). Friendship formation. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp.29–54). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Ferrie, J. E., Shipley, M. J., Cappuccio, F. P., Brunner, E., Miller, M. A., Kumari, M., & Marmot, M. G. (2007). A prospective study of change in sleep duration: Associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep, 30(12), 1659.

Ford, E. S., Li, C., & Zhao, G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of metabolic syndrome based on a harmonious definition among adults in the US. Journal of Diabetes, 2(3), 180-193.

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. (1959). Association of specific overt behaviour pattern with blood and cardiovascular findings. Journal of the American Medical Association, 169, 1286–1296.

Fry, R. (2017). It’s becoming more common for young adults to live at home-and for longer stretches. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/05/its-becoming-more-common-for-young-adults-to-live-at-home-and-for-longer-stretches/ft_17-05-03_livingathome_bygen2/

Füllgrabe, C., Moore, B. C. J., & Stone, M. A. (2015). Age-group differences in speech identification despite matched audio metrically normal hearing: contributions from auditory temporal processing and cognition. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 1-25. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00347

Fung, H. H. (2013). Aging in culture. Gerontologist, 53(3), 369-377.

Gerstel, N., & Gallagher, S. K. (1993). Kinkeeping and distress: Gender, recipients of care, and work–family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 598–607.

Gibbons, C., Creese, J., Tran, M., Brazil, K., Chambers, L., Weaver, B., & Bedard, M. (2014). The psychological and health consequences of caring for a spouse with dementia: A critical comparison of husbands and wives. Journal of Women & Aging, 26, 3-21.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (2000). Cultures of aging: Self, citizen and the body. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Publishers.

Goldscheider, F., & Kaufman, G. (2006). Willingness to stepparent: Attitudes about partners who already have children. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1415 – 1436.

Goldscheider, F., & Sassler, S. (2006). Creating stepfamilies: Integrating children into the study of union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 275 – 291.

Gorchoff, S. M., John, O. P., & Helson, R. (2008). Contextualizing change in marital satisfaction during middle age. Psychological Science, 19, 1194–1200.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2000). The timing of divorce: Predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62, 737-745.

Greene, S. M., Anderson, E. R., Hetherington, E., Forgtch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2003). Risk and resilience after divorce. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ed., pp. 96-120). New York: Guilford Press.

Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 442-454.

Greenfield, E. A., Vaillant, G. E., & Marks, N. F. (2009). Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 196-212.

Gripsrud, J. (2007). Television and the European public sphere. European Journal of Communication, 22, 479-492.

Grzywacz, J. G. & Keyes, C. L. (2004). Toward health promotion: Physical and social behaviors in complete health. Journal of Health Behavior, 28(2), 99-111.

Ha, J., Hong, J., Seltzer, M. M., & Greenberg, J. S. (2008). Age and gender differences in the well-being of midlife and aging parents with children with mental health or developmental problems: Report of a national study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 301-316.

Harrison, J., Barrow, S., Gask, L., & Creed, F. (1999). Social determinants of GHQ score by postal survey. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 21, 283–288. doi:10.1093/pubmed/21.3.283

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and marital status transitions and health outcomes social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, 375–384. doi:10.1093/geronb/ 63.6.S375

Hayslip Jr., B., Henderson, C. E., & Shore, R. J. (2003). The Structure of Grandparental Role Meaning. Journal of Adult Development, 10(1), 1-13.

Hedlund, J., Antonakis, J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Tacit knowledge and practical intelligence: Understanding the lessons of experience. Retrieved from www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/army/ari_tacit_knowledge.pdf

Herman-Stabl, M. A., Stemmler, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1995). Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 649–665.

Hetherington, E. M. & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York, NY: Norton.

Holland, K. (2014). Why America’s campuses are going gray. CNBC. Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2014/08/28/why-americas-campuses-are-going-gray.html

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Hooker, E., & Pressman, S. (2016). The healthy life. NOBA. Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-healthy-life

Horn, J. L., Donaldson, G., & Engstrom, R. (1981). Apprehension, memory, and fluid intelligence decline in adulthood. Research on Aging, 3(1), 33-84.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545

Hu, G., Qiao, Q., Tuomilehto, J., Balkau, B., Borch, Johnsen, K., & Pyorala, K. (2004). Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its relation to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in non-diabetic European men and women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(10), 1066-1076.

Huang, J. (2007). Hormones and female sexuality. In M. Tepper & A. F. Owens (Eds.), Sexual Health, Vol 2: Physical Foundations (pp. 43-78). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Humes, L. E., Kewley-Port, D., Fogerty, D., & Kinney, D. (2010). Measures of hearing threshold and temporal processing across the adult lifespan. Hearing Research, 264(1/2), 30-40. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2009.09.010

International Labour Organization. (2011). Global Employment Trends: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_150440.pdf

Iribarren, C., Sidney, S., Bild, D. E., Liu, K., Markovitz, J. H., Roseman, J. M., & Matthews, K. (2000). Association of hostility with coronary artery calcification in young adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 2546–2551.

Jackson, G. R. & Owsley, C. (2000). Scotopic sensitivity during adulthood. Vision Research, 40 (18), 2467-2473. doi:10.1016/S0042-6989(00)00108-5

Jones, J. M. (2013). In U.S., 40% Get Less than Recommended Amount of Sleep. Gallup. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/166553/less-recommended- amountsleep.aspx?g_source=sleep%202013&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles

Kagawa-Singer, M., Wu, K., & Kawanishi, Y. (2002). Comparison of the menopause and midlife transition between Japanese American and European American women. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 16(1), 64-91.

Kang, S. W., & Marks, N. F. (2014). Parental caregiving for a child with special needs, marital strain, and physical health: Evidence from National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. 2005. Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research, 8A, 183- 209.

Karakelides, H., & Nair, K. S. (2005). Sarcopenia of aging and its metabolic impact. Current Topics in Developmental Biology, 68, 123-148.

Kasper, T. (2015). Why you only need 7 hours of sleep. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Retrieved from http://sleepeducation.org/news/2015/06/03/why-you-only-need-7-hours-of-sleep

Kaufman, B. E., & Hotchkiss, J. L. 2003. The economics of labor markets (6th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Kaufman, S. B., & Gregoire, C. (2016). How to cultivate creativity. Scientific American Mind, 27 (1), 62-67.

Kaur, S., Walia, I., & Singh, A. (2004). How menopause affects the lives of women in suburban Chandigarh, India. Climacteric, 7(2), 175-180.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (1998). The adult learner: A neglected species. Houston: Gulf Pub., Book Division.

Kochanek, K. D., Murphy, S. L., Xu, J., & Arias, E. (2019). Deaths: Final data for 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports, 68(9), 1-77.

Kouzis, A. C., & Eaton, W. W. (1998). Absence of social networks, social support, and health services utilization. Psychological Medicine, 28, 1301–1310. doi:10.1017/S0033291798007454

Krause, N. A., Herzog, R., & Baker, E. (1992). Providing support to others and well-being in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 47, P300-311.

Kühnel, J., & Sonnentag, S. (2011). How long do you benefit from vacation? A closer look at the fade-out vacation effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 125-143.

Kushida, C. (2005). Sleep deprivation: basic science, physiology, and behavior. London, England: Informal Healthcare.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305-331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521

Landsford, J. E., Antonucci, T.C., Akiyama, H., & Takahashi, K. (2005). A quantitative and qualitative approach to social relationships and well-being in the United States and Japan. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 1-22.

Leach, M. S., & Braithwaite, D. O. (1996). A binding tie: Supportive communication of family kinkeepers. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 24, 200–216.

Lee, B., Lawson, K. M., Chang, P., Neuendorf, C., Dmitrieva, N. O., & Ameida, D. H. (2015). Leisure-time physical activity moderates the longitudinal associations between work-family spillover and physical health. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(4), 444-466.

Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Knopf.

Livingston, G. (2014). Four in ten couples are saying I do again. In Chapter 3. The differing demographic profiles of first-time marries, remarried and divorced adults. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/chapter-3-the-differing-demographic-profiles-of-first-time-married-remarried-and-divorced-adults/

Madden, S., St Pierre-Hansen, N., & Kelly L. (2010). First Nations women’s knowledge of menopause: Experiences and perspectives. Canadian Family Physician, 56(9), e331-e337.

Malik, S. (2004). Impact of the metabolic syndrome on mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in United States adults. Circulation, 110(10), 1245-1250.

Malone, J. C., Liu, S. R., Vaillant, G. E., Rentz, D. M., & Waldinger, R. J. (2016). Midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development: Setting the stage for late-life cognitive and emotional health. Developmental Psychology, 52(3), 496-508.

Marketing Charts Staff. (2014). Are young people watching less TV? Retrieved from http://www.marketingcharts.com/television/are-young-people-watching-less-tv-24817/

Martin, L. J. (2014). Aging changes in hair and nails. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/004005.htm

Matthews, K. A., Glass, D. C., Rosenman, R. H., & Bortner, R. W. (1977). Competitive drive, pattern A, and coronary heart disease: A further analysis of some data from the Western Collaborative Group Study. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 30, 489–498.

Mayo Clinic. (2014a). Heart disease. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/basics/definition/con-20034056

Mayo Clinic. (2014b). Metabolism and weight loss: How you burn calories. Retrieved from www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/weight-loss/in-depth/metabolism/art-20046508

McKenna, K. A. (2008) MySpace or your place: Relationship initiation and development in the wired and wireless world. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 235–247). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

McKenna, K. A., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the Internet: What’s the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58, 9–31.

Metlife. (2011). Metlife study of caregiving costs to working caregivers: Double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/mmi-caregiving-costs-working-caregivers.pdf

Maillard, P., Sashardi, S., Beiser, A., Himail, J. J., Au, R., Fletcher, E., …. DeCarli, C. (2012). Effects of systolic blood pressure on white-matter integrity in young adults in the Farmington Heart Study: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet: Neurology, 11(12), 1039-1047.

Miller, T. Q., Smith, T. W., Turner, C. W., Guijarro, M. L., & Hallet, A. J. (1996). Meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 322–348.

Mitchell, B. A., & Lovegreen, L. D. (2009). The empty nest syndrome in midlife families: A multimethod exploration of parental gender differences and cultural dynamics. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1651–1670.

Montenegro, X. P. (2003). Lifestyles, dating, and romance: A study of midlife singles. Washington, DC: AARP.

Monthly Labor Review. (2013). Percentage of the non-institutionalized civilian workforce employed by gender & age. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/cps_aa2013.htm

Moravec, C. S. (2008). Biofeedback therapy in cardiovascular disease: rationale and research overview. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 75, S35–S38.

Morita, Y., Iwamoto, I., Mizuma, W., Kuwahata, T., Matsuo, T., Yoshinaga, M., &Douchi, T. (2006). Precedence of the shift of body-fat distribution over the change in body composition after menopause. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 32, 513-516.

Morley, J. E., Baumgartner, R. N., Roubenoff, R., Mayer, J., & Nair, K. S. (2001). Sarcopenia. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 137(4), 231-243.

Moskowitz, R. J. (2014). Wrinkles. U. S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003252.htm

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89-105). New York: Oxford University Press.

Nassir, F., Rector, S., Hammoud, G.M., & Ibdah, J.A. (2015). Pathogenesis and prevention of hepatic steatosis. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(3), 167-175.

National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Retrieved from www.caregiving.org/caregiving2015.

National Eye Institute. (2009). Facts about floaters. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from nei.nih.gov/health/floaters/floaters

National Eye Institute. (2013). Facts about dry eye. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from nei.nih.gov/health/dryeye/dryeye

National Eye Institute. (2015). Facts about diabetic eye disease. Retrieved from: nei.nih.gov/health/diabetic/retinopathy

National Eye Institute. (2016). Facts about presbyopia. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from nei.nih.gov/health/errors/presbyopia

National Institutes of Health. (2007). Menopause: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000894.htm

National Institutes of Health. (2013). Gallstones. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/gallstones/Pages/facts.aspx

National Institutes of Health. (2014a). The A1C and diabetes. Retrieved from www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/diagnostic-tests/a1c-test-diabetes/Pages/index.aspx

National Institutes of Health (2014b). Age changes in the lungs. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/004011.htm

National Institutes of Health (2014c). Sweet stuff: How sugars and sweeteners affect your health. Retrieved from https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/issue/oct2014/feature1

National Institutes of Health. (2014d). What is atherosclerosis? Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/atherosclerosis

National Institutes of Health. (2015). Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

National Institutes of Health. (2016a). Facts about diabetes. Retrieved from www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/Diabetes/diabetes-facts/Pages/default.aspx

National Institutes of Health (2016b). Handout on Health: Rheumatoid Arthritis. Retrieved from http://www.niams.nih.gov/health%5Finfo/rheumatic%5Fdisease/

National Institutes of Health. (2016c). Older drivers: How health affects driving. Retrieved from nihseniorhealth.gov/olderdrivers/howhealthaffectsdriving/01.html

National Sleep Foundation. (2015). 2015 Sleep in America™ poll finds pain a significant challenge when it comes to Americans’ sleep. National Sleep Foundation. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/media-center/press-release/2015-sleep-america-poll

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Menopause and Insomnia. National Sleep Foundation. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/ask-the-expert/menopause-and-insomnia

Neidleman, M. T., Wambacq, I., Besing, J., Spitzer, J. B., & Koehnke, J. (2015). The Effect of Background Babble on Working Memory in Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26(3), 220-228. doi:10.3766/jaaa.26.3.3

Neugarten, B. L. (1968). The awareness of middle aging. In B. L. Neugarten (Ed.), Middle age and aging (pp. 93-98). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Neugarten, B. L., & Weinstein, K. K. (1964). The changing American grandparent. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 26, 199–204.

Newton, T., Buckley, A., Zurlage, M., Mitchell, C., Shaw, A., & Woodruff-Borden, J. (2008). Lack of a close confidant: Prevalence and correlates in a medically underserved primary care sample. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13, 185– 192. doi:10.1080/ 13548500701405491

Nimrod, G., Kleiber, D. A., & Berdychevesky, L. (2012). Leisure in coping with depression. Journal of Leisure Research, 44(4), 414-449.

Norman, G. (2005). Research in clinical reasoning: Past history and current trends. Medical Education, 39, 418–427. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02127.x

North American Menopause Society. (2016). Menopause FAQs: Understanding the symptoms. Retrieved from Http://www.menopause.org/for-women/expert-answers-to-frequently-asked-questions-about-menopause/menopause-faqs-understanding-the-symptoms

Nwankwo T., Yoon S. S., Burt, V., & Gu, Q. (2013) Hypertension among adults in the US: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief, No. 133. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2008). The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Retrieved from http://health.gov/paguidelines/?_ga=1.177233189.1671103883.1467228401

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2016). Average annual hours actually worked per worker. OECD Stat. Retrieved from stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ANHRS

Palacios, S., Henderson V. W., & Siseles, N. (2010). Age of menopause and impact of climacteric symptoms by geographical region. Climacteric, 13(5), 419-428.

Parker, K. & Patten, E. (2013). The sandwich generation: Rising financial burdens for middle-aged Americans. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/01/30/the-sandwich-generation/

Patel, C., Marmot, M. G., & Terry, D. J. (1981). Controlled trial of biofeedback-aided behavioural methods in reducing mild hypertension. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.), 282, 2005–2008.

Pattison, K. (2015). Sleep deficit. Experience Life. Retrieved from https://experiencelife.com/article/sleep-deficit/

Payne, K. K. (2015). The remarriage rate: Geographic variation, 2013. National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from http://bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/payne-remarriage-rate-fp-15-08.html

Peterson, B. E. & Duncan, L. E. (2007). Midlife women’s generativity and authoritarianism: Marriage, motherhood, and 10 years of aging. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 411-419.

Peterson, B. E., Smirles, K. A., & Wentworth, P. A. (1997). Generativity and authoritarianism: Implications for personality, political involvement, and parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1202-1216.

Pew Research Center. (2010). The return of the multi-generational family household. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/03/18/the-return-of-the-multi-generational-family-household/

Pew Research Center. (2010a). How the great recession has changed life in America. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/30/how-the-great-recession-has-changed-life-in-america/

Pew Research Center. (2010b). Section 5: Generations and the great recession. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2011/11/03/section-5-generations-and-the-great-recession/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Caring for aging parents. Family support in graying societies. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/21/4-caring-for-aging-parents/

Pew Research Center. (2016). The Gender gap in religion around the world. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/22/the-gender-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/

Phillips, M. L. (2011). The mind at midlife. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/04/mind-midlife.aspx

Proctor, D. N., Balagopal, P., & Nair, K. S. (1998). Age-related sarcopenia in humans is associated with reduced synthetic rates of specific muscle proteins. Journal of Nutrition, 128(2 Suppl.), 351S-355S.

Project Time-Off (2016). The state of American vacation: How vacation became a casualty of our work culture. Retrieved from www.projecttimeoff.com/research/state-american-vacation-2016

Qian, X., Yarnal, C. M., Almeida, D. M. (2013). Does leisure time as a stress coping source increase affective complexity? Applying the Dynamic Model of Affect (DMA). Journal of Leisure Research, 45(3), 393-414.

Ray, R., Sanes, M., & Schmitt, J. (2013). No-vacation nation revisited. Center for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved from cepr.net/publications/reports/no-vacation-nation-2013

Ray, R., & Schmitt, J. (2007). No vacation nation USA – A comparison of leave and holiday in OECD countries. Retrieved from http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/lwp/papers/No_Holidays.pdf

Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. (2007, February 7). Midlife Research – MIDMAC WebSite. Retrieved from midmac.med.harvard.edu/research.html

Riordan, C. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (1995). The opportunity for friendship in the workplace: An underexplored construct. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 141–154.

Rossi, A. S. (2004). The menopausal transition and aging process. In How healthy are we: A national study of health in midlife. (pp. 550-575). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rubin, M., Scevak, J., Southgate, E., Macqueen, S., Williams, P., & Douglas, H. (2018). Older women, deeper learning, and greater satisfaction at university: Age and gender predict university students’ learning approach and degree satisfaction. Diversity in Higher Education, 11(1), 82-96.

Saad, L. (2014). The 40 hour work week is actually longer – by 7 hours. Gallop. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/175286/hour-workweek-actually-longer-seven-hours.aspx

Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 33–61.

Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 140–144. Sandgerg-Thoma, S. E., Synder, A. R., & Jang, B. J. (2015). Exiting and returning to the parental home for boomerang kids. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 806-818. doi:10.1111/jomf.12183

Sawatzky, R., Ratner, P. A., & Chiu, L. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 72, 153-188.

Schaie, K. W. (2005). Developmental influences on adult intelligence the Seattle longitudinal study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scheibe, S., Kunzmann, U. & Baltes, P. B. (2009). New territories of Positive Lifespan Development: Wisdom and Life Longings. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S., A., Dodge, B., Middlestadt, S. E., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: Implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(Suppl. 5), 315-329.

Schuler, P., Vinci, D., Isosaari, R., Philipp, S., Todorovich, J., Roy, J., & Evans, R. (2008). Body-shape perceptions and body mass index of older African American and European American women. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23(3), 255-264.

Schulz, R., Newsom, J., Mittelmark, M., Burton, L., Hirsch, C., & Jackson, S. (1997). Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 110-116.

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Seltzer, M. M., Floyd, F., Song, J., Greenberg, J., & Hong, J. (2011). Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 116, 479-499.

Selye, H. (1946). The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology, 6, 117– 230.

Shure, J., & Cahan, V. (1998, September 10). Launch an exercise program today, say Aging Institute, Senator John Glenn. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from www.nia.nih.gov/NewsAndEvents/PressReleases/PR19980910Launch.htm

Slevin, K. F. (2010). “If I had lots of money…I’d have a body makeover”: Managing the aging body. Social Forces, 88(3), 1003-1020.

Sorensen, P., & Cooper, N. J. (2010). Reshaping the family man: A grounded theory study of the meaning of grandfatherhood. Journal of Men’s Studies, 18(2), 117-136. doi:10.3149/jms.1802.117

Spiegel, D., Kraemer, H., Bloom, J., & Gottheil, E. (1989). Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. The Lancet, 334, 888–891.

Stern, C., & Konno, R. (2009). Physical Leisure activities and their role in preventing dementia: A systematic review. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 7, 270-282.

Stewart, S. D., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Union formation among men in the US: Does having prior children matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 90 – 104.

Su, D., Wu, X., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Zhang, J., & Zhou, L. (2012). Depression and social support between China’ rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55, 564–569.

Swierzewski, S. J. (2015). Erectile Dysfunction. Retrieved from http://www.healthcommunities.com/erectile-dysfunction/overview-of-impotence.shtml

Tangri, S., Thomas, V., & Mednick, M. (2003). Prediction of satisfaction among college-educated African American women. Journal of Adult Development, 10, 113-125.

Taylor, B. J., Matthews, K. A., Hasler, B. P., Roecklein, K. A., Kline, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Kravitz, H. M., Tiani, A. G., Harlow, S. D., & Hall, M. H. (2016). Bedtime variability and metabolic health in midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. SLEEP, 39(2), 457–465.

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107, 411–429.

Teachman, J. (2008). Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 294 – 305.

Teuscher, U., & Teuscher, C. (2006). Reconsidering the double standard of aging: Effects of gender and sexual orientation on facial attractiveness ratings. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(4), 631-639.

Thurston, W. E, & Vissandjée, B. (2005). An ecological model for understanding culture as a determinant of women’s health. Critical Public Health, 15(3), 229-242.

Torti, F. M., Gwyther, L. P., Reed, S. D., Friedman, J. Y., & Schulman, K. A. (2004). A multinational review of recent trends and reports in dementia caregiver burden. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 18(2), 99-109.

Tower, R. B., & Kasl, S. V. (1995). Depressive symptoms across older spouses and the moderating effect of marital closeness. Psychology and Aging, 10, 625– 638. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.10.4.625

Twisk, J. W., Snel, J., Kemper, H. C., & van Mechelen, W. (1999). Changes in daily hassles and life events and the relationship with coronary heart disease risk factors: A 2-year longitudinal study in 27–29-year-old males and females. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46, 229–240.

Uchida, Y., Nakashima, T., Ando, F., Niino, N., & Shimokata, H. (2003). Prevalence of self-perceived auditory problems and their relation to audiometric thresholds in a middle-aged to elderly population. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 123(5), 618.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D., Chen, M., & Campbell, A. (2005). As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 81, 493-511.

United Health Foundation. (2016). New report finds significant health concerns loom for seniors in coming years. Retrieved from http://www.unitedhealthfoundation.org/News/Articles/Feeds/2016/052516AHRSeniorReport.aspx?r=3

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). American time use survey – 2015. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/atus.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015) 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. Retrieved from http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

U.S. Department of Labor (2016). Vacation Leave. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/workhours/vacation_leave

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2012). Unemployed older workers: Many experience challenges regaining employment and face reduced retirement security. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-445

Vaillant, G. E. (1977). Adaptation of life. Boston, MA: Little, Brown