7.2: Prejudice and Discrimination

- Page ID

- 57580

Prejudice and Discrimination

Prejudice is a negative attitude and feeling toward an individual based solely on one’s membership in a particular social group, such as gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, social class, religion, sexual orientation, profession, and many more (Allport, 1954; Brown, 2010). An example of prejudice is having a negative attitude toward people who are not born in the United States. Although people holding this prejudiced attitude do not know all people who were not born in the United States, they dislike them due to their status as foreigners.

Identifying Prejudice

Because stereotypes and prejudice often operate out of our awareness, and also because people are frequently unwilling to admit that they hold them, social psychologists have developed methods for assessing them indirectly.These implicit biases are unexamined and sometimes unconscious but real in their consequences. They are automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent, but nonetheless biased, unfair, and disrespectful to the belief in equality.

Other indirect measures of prejudice are also frequently used in intercultural communication research, for instance—assessing nonverbal behaviors such as speech errors or physical closeness. One common measure involves asking participants to take a seat on a chair near a person from a different racial or ethnic group and measuring how far away the person sits (Sechrist & Stangor, 2001; Word, Zanna, & Cooper, 1974). People who sit farther away are assumed to be more prejudiced toward the members of the group.

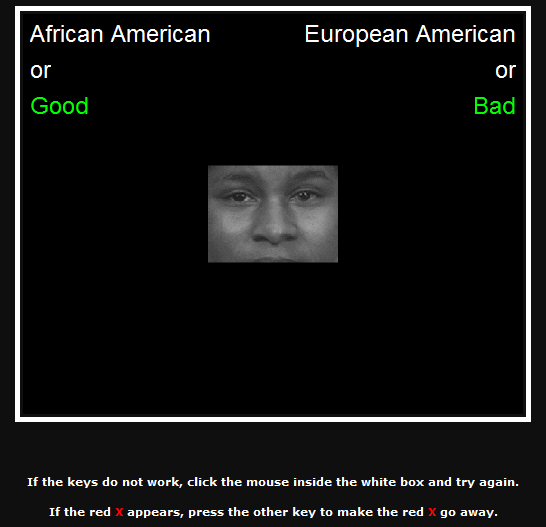

Because our stereotypes are activated spontaneously when we think about members of different social groups, it is possible to use reaction-time measures to assess this activation and thus to learn about people’s stereotypes and prejudices. In these procedures, participants are asked to make a series of judgments about pictures or descriptions of social groups and then to answer questions as quickly as they can, but without making mistakes. The speed of these responses is used to determine an individual’s stereotypes or prejudice.

The most popular reaction-time implicit measure of prejudice—the Implicit Association Test (IAT)—is frequently used to assess stereotypes and prejudice (Nosek, Greenwald, & Banaji, 2007). The test itself is rather simple and you can experience it yourself if you Google “implicit” or go to understandingprejudice.org. In the IAT, participants are asked to classify stimuli that they view on a computer screen into one of two categories by pressing one of two computer keys, one with their left hand and one with their right hand. Furthermore, the categories are arranged such that the responses to be answered with the left and right buttons either “fit with” (match) the stereotype or do not “fit with” (mismatch) the stereotype. For instance, in one version of the IAT, participants are shown pictures of men and women and also shown words related to gender stereotypes (e.g., strong, leader, or powerful for men and nurturing, emotional, or weak for women). Then the participants categorize the photos (“Is this picture a picture of a man or a woman?”) and answer questions about the stereotypes (“Is this the word strong?) by pressing either the Yes button or the No button using either their left hand or their right hand.

When the responses are arranged on the screen in a “matching” way, such that the male category and the “strong” category are on the same side of the screen (e.g., on the right side), participants can do the task very quickly and they make few mistakes. It’s just easier, because the stereotypes are matched or associated with the pictures in a way that makes sense. But when the images are arranged such that the women and the strong categories are on the same side, whereas the men and the weak categories are on the other side, most participants make more errors and respond more slowly. The basic assumption is that if two concepts are associated or linked, they will be responded to more quickly if they are classified using the same, rather than different, keys.

Implicit association procedures such as the IAT show that even participants who claim that they are not prejudiced do seem to hold cultural stereotypes about social groups. Even Black people themselves respond more quickly to positive words that are associated with White rather than Black faces on the IAT, suggesting that they have subtle racial prejudice toward Blacks.

Because they hold these beliefs, it is possible—although not guaranteed—that they may use them when responding to other people, creating a subtle and unconscious type of discrimination. Although the meaning of the IAT has been debated (Tetlock & Mitchell, 2008), research using implicit measures does suggest that—whether we know it or not, and even though we may try to control them when we can—our stereotypes and prejudices are easily activated when we see members of different social categories (Barden, Maddux, Petty, & Brewer, 2004).

In one particularly disturbing line of research about the influence of prejudice on behaviors, Joshua Correll and his colleagues had White participants participate in an experiment in which they viewed photographs of White and Black people on a computer screen. Across the experiment, the photographs showed the people holding either a gun or something harmless such as a cell phone. The participants were asked to decide as quickly as possible to press a button to “shoot” if the target held a weapon but to “not shoot” if the person did not hold a weapon. Overall, the White participants tended to shoot more often when the person holding the object was Black than when the person holding the object was White, and this occurred even when there was no weapon present (Correll, Park, Judd, & Wittenbrink, 2007; Correll et al., 2007).

Explaining Prejudice

As discussed previously in this section, we all belong to a gender, race, age, and social economic group. These groups provide a powerful source of our identity and self-esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). These groups serve as our ingroups. An ingroup is a group that we identify with or see ourselves as belonging to. A group that we don’t belong to, or an outgroup, is a group that we view as fundamentally different from us. For example, if you are female, your gender ingroup includes all females, and your gender outgroup includes all males. People often view gender groups as being fundamentally different from each other in personality traits, characteristics, social roles, and interests. Perceiving others as members of ingroups or outgroups is one of the most important perceptual distinctions that we make. We often feel strongly connected to our ingroups, especially when they are centrally tied to our identities and culture. Because we often feel a strong sense of belonging and emotional connection to our ingroups, we develop ingroup favoritism—the tendency to respond more positively to people from our ingroups than we do to people from outgroups.

People also make trait attributions in ways that benefit their ingroups, just as they make trait attributions that benefit themselves. This general tendency, known as the ultimate attribution error, results in the tendency for each of the competing groups to perceive the other group extremely and unrealistically negatively (Hewstone, 1990). When an ingroup member engages in a positive behavior, we tend to see it as a stable internal characteristic of the group as a whole. Similarly, negative behaviors on the part of the outgroup are seen as caused by stable negative group characteristics. On the other hand, negative behaviors from the ingroup and positive behaviors from the outgroup are more likely to be seen as caused by temporary situational variables or by behaviors of specific individuals and are less likely to be attributed to the group. For example, if your friend (someone you perceive as part of your ingroup) does well on an exam, you might account for that by stating that your friend is smart and studied well for the exam. But if someone who you consider as part of your outgroup, such as an international student, does well on an exam, then the reason attributed is that the subject matter is easy, or the professor gives easy exams. Similarly, if your friend does poorly on an exam, you may blame the difficulty of the subject matter or the professor for making unfair exams. If an international student does poorly on an exam, the tendency is to see it as a group trait (international students tend to do poorly on exams). This ingroup bias can result in prejudice and discrimination because the outgroup is perceived as different and is less preferred than our ingroup.

A personality dimension that relates to the desires to protect and enhance the self and the ingroup and thus also relates to greater ingroup favoritism, and in some cases prejudice toward outgroups, is the personality dimension of authoritarianism (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950; Altemeyer, 1988). Authoritarianism is a personality dimension that characterizes people who prefer things to be simple rather than complex and who tend to hold traditional and conventional values. Authoritarians are ingroup-favoring in part because they have a need to self-enhance and in part because they prefer simplicity and thus find it easy to think simply: “We are all good and they are all less good.” Political conservatives tend to show more ingroup favoritism than do political liberals, perhaps because the former are more concerned with protecting the ingroup from threats posed by others (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003; Stangor & Leary, 2006). Authoritarian personalities develop in childhood in response to parents who practice harsh discipline. Individuals with authoritarian personalities emphasize such things as obedience to authority, a rigid adherence to rules, and low acceptance of people (outgroups) not like oneself. Many studies find strong racial and ethnic prejudice among such individuals (Sibley & Duckitt, 2008). But whether their prejudice stems from their authoritarian personalities or instead from the fact that their parents were probably prejudiced themselves remains an important question.

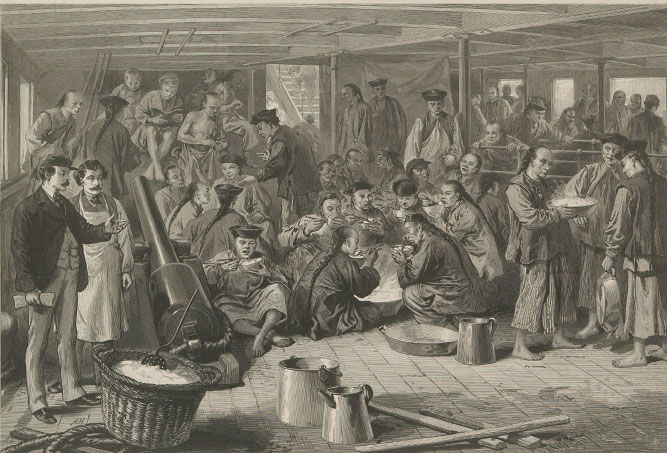

Developed initially from John Dollard’s (1900-1980) frustration-aggression theory, Scapegoating is the act of blaming a subordinate group when the dominant group experiences frustration or is blocked from obtaining a goal (Allport, 1954). History provides many examples: The lynchings of African Americans in the South increased when the Southern economy worsened and decreased when the economy improved (Tolnay & Beck, 1995). Similarly, white mob violence against Chinese immigrants in the 1870s began after the railroad construction that employed so many Chinese immigrants slowed and the Chinese began looking for work in other industries. Whites feared that the Chinese would take jobs away from white workers and that their large supply of labor would drive down wages. Their assaults on the Chinese killed several people and prompted the passage by Congress of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that prohibited Chinese immigration (Dinnerstein & Reimers, 2009). An example from the last century is the way that Adolf Hitler was able to use the Jewish people as scapegoats for Germany’s social and economic problems. In the United States, many states have enacted laws to disenfranchise immigrants; these laws are popular because they let the dominant group scapegoat a subordinate group. Many minority groups have been scapegoated for a nation’s — or an individual’s — woes.

One popular explanation of prejudice emphasizes conformity and socialization and is called social learning theory. In this view, people who are prejudiced are merely conforming to the culture in which they grow up, and prejudice is the result of socialization from parents, peers, the news media, Facebook, and other various aspects of their culture. Supporting this view, studies have found that people tend to become more prejudiced when they move to areas where people are very prejudiced and less prejudiced when they move to locations where people are less prejudiced (Aronson, 2008).

The mass media play a key role in how many people learn to be prejudiced. This type of learning happens because the media often present people of color in a negative light. By doing so, the media reinforce the prejudice that individuals already have or even increase their prejudice (Larson, 2005). Examples of distorted media coverage abound. Even though poor people are more likely to be white than any other race or ethnicity, the news media use pictures of African Americans far more often than those of whites in stories about poverty. In one study, national news magazines, such as Time and Newsweek, and television news shows portrayed African Americans in almost two-thirds of their stories on poverty, even though only about one-fourth of poor people are African Americans. In the magazine stories, only 12 percent of the African Americans had a job, even though in the real world more than 40 percent of poor African Americans were working at the time the stories were written (Gilens, 1996). In a Chicago study, television news shows there depicted whites fourteen times more often in stories of good Samaritans, even though whites and African Americans live in Chicago in roughly equal numbers (Entman & Rojecki, 2001). Many other studies find that newspaper and television stories about crime and drugs feature higher proportions of African Americans as offenders than is true in arrest statistics (Surette, 2011). Studies like these show that the news media “convey the message that black people are violent, lazy, and less civic minded” (Jackson, 1997, p. A27).

Discrimination

Prejudice and discrimination are often confused, but the basic difference between them is this: Prejudice is the attitude, while discrimination is the behavior. Sometimes people will act on their prejudiced attitudes toward a group of people, and this behavior is known as discrimination. More specifically, Discrimination in this context refers to the arbitrary denial of rights, privileges, and opportunities to members of these groups. The use of the word arbitrary emphasizes that these groups are being treated unequally not because of their lack of merit but because of one’s membership in a particular group (Allport, 1954; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). As a result of holding negative beliefs (stereotypes) and negative attitudes (prejudice) about a particular group, people often treat the target of prejudice poorly.

Examples of Discrimination

When we meet strangers we automatically process three pieces of information about them: their race, gender, and age (Ito & Urland, 2003). Why are these aspects of an unfamiliar person so important? Why don’t we instead notice whether their eyes are friendly, whether they are smiling, their height, the type of clothes they are wearing? Although these secondary characteristics are important in forming a first impression of a stranger, the social categories of race, gender, and age provide a wealth of information about an individual. This information, however, is based on stereotypes, and prejudice and discrimination often begin in the form of stereotypes.

Racism

Racism is a type of prejudice that is used to justify the belief that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others. Racial discrimination is discrimination against an individual based solely on one’s membership in a specific racial group (such as toward African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, Arab Americans, etc.). For example, Blacks are significantly more likely to have their vehicles searched during traffic stops than Whites, particularly when Blacks are driving in predominately White neighborhoods, (a phenomenon often termed “DWB,” or “driving while Black.”) (Rojek, Rosenfeld, & Decker, 2012). Mexican Americans and other Latinx groups also are targets of racism from the police and other members of the community. For example, when purchasing items with a personal check, Latinx shoppers are more likely than White shoppers to be asked to show formal identification (Dovidio et al., 2010).

In one case of alleged harassment by the police, several East Haven, Connecticut, police officers were arrested on federal charges due to reportedly continued harassment and brutalization of Latinx people. When the accusations came out, the mayor of East Haven was asked, “What are you doing for the Latino community today?” The Mayor responded, “I might have tacos when I go home, I’m not quite sure yet” (“East Haven Mayor,” 2012) This statement undermines the important issue of racial profiling and police harassment of Latinx people, while belittling Latinx culture by emphasizing an interest in a food product stereotypically associated with Latinx people. We will discuss racism with more depth in the next section.

Sexism

Sexism is prejudice and discrimination toward individuals based on their sex. Typically, sexism takes the form of men holding biases against women, but either sex can show sexism toward their own or the other sex. Common forms of sexism in modern society include gender role expectations, such as expecting women to be the caretakers of the household. Sexism also includes people’s expectations for how members of a gender group should behave. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing, and when women behave in an unfriendly, assertive, or neglectful manner they often are disliked for violating their gender role (Rudman, 1998). Research by Laurie Rudman (1998) finds that when female job applicants self-promote, they are likely to be viewed as competent, but they may be disliked and are less likely to be hired because they violated gender expectations for modesty. Sexism can exist on a societal level such as in hiring, employment opportunities, and education. Women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions such as engineering, aviation, and construction (Blau, Ferber, & Winkler, 2010; Ceci & Williams, 2011).

Heterosexism

Homophobia is a widespread prejudice in U.S. society that is tolerated by many people (Herek & McLemore, 2013; Nosek, 2005) and often results in heterosexist discrimination, such as the exclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people from social groups and the avoidance of LGBTQ neighbors and co-workers. This discrimination also extends to employers deliberately declining to hire qualified LGBTQ job applicants. Some people are quite passionate in their hatred for nonheterosexuals in our society. In some cases, people have been tortured and/or murdered simply because they were not heterosexual. This passionate response has led some researchers to question what motives might exist for homophobic people. Adams, Wright, & Lohr (1996) conducted a study investigating this issue and their results were quite an eye-opener.

In this experiment, male college students were given a scale that assessed how homophobic they were; those with extreme scores were recruited to participate in the experiment. In the end, 64 men agreed to participate and were split into 2 groups: homophobic men and nonhomophobic men. Both groups of men were fitted with a penile plethysmograph, an instrument that measures changes in blood flow to the penis and serves as an objective measurement of sexual arousal.

All men were shown segments of sexually explicit videos. One of these videos involved a sexual interaction between a man and a woman (heterosexual clip). One video displayed two females engaged in a sexual interaction (homosexual female clip), and the final video displayed two men engaged in a sexual interaction (homosexual male clip). Changes in penile tumescence were recorded during all three clips, and a subjective measurement of sexual arousal was also obtained. While both groups of men became sexually aroused to the heterosexual and female homosexual video clips, only those men who were identified as homophobic showed sexual arousal to the homosexual male video clip. While all men reported that their erections indicated arousal for the heterosexual and female homosexual clips, the homophobic men indicated that they were not sexually aroused (despite their erections) to the male homosexual clips. Adams et al. (1996) suggest that these findings may indicate that homophobia is related to homosexual arousal that the homophobic individuals either deny or are unaware.

Ageism

People often form judgments and hold expectations about people based on their age. These judgments and expectations can lead to ageism. Typically, ageism occurs against older adults, but ageism also can occur toward younger adults. Ageism is widespread in U.S. culture (Nosek, 2005), and a common ageist attitude toward older adults is that they are incompetent, physically weak, and slow (Greenberg, Schimel, & Martens, 2002) and some people consider older adults less attractive. Some cultures, however, including some Asian, Latinx, and African American cultures, both outside and within the United States afford older adults respect and honor.

Types of Discrimination

Individual Discrimination

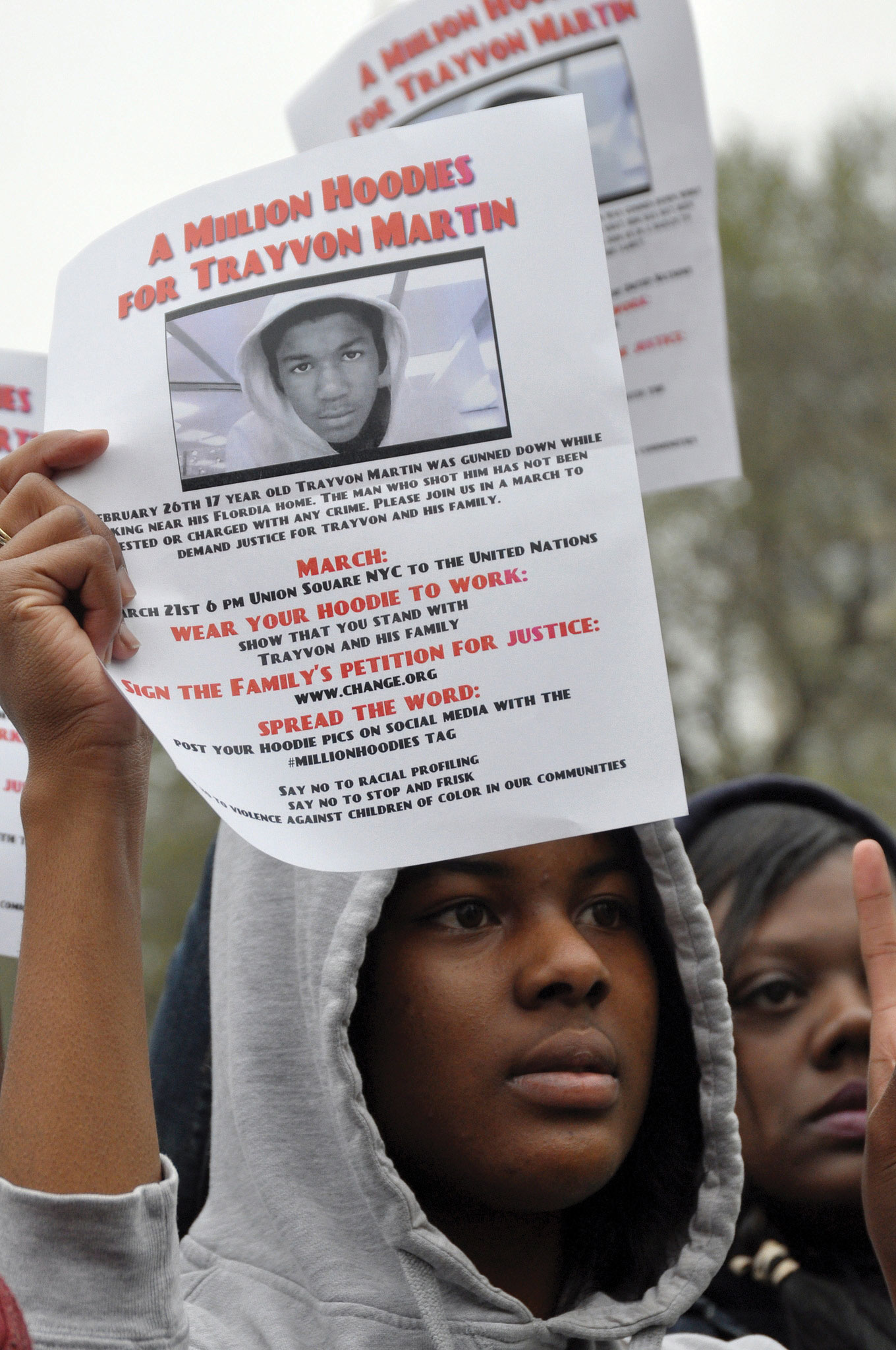

Individual discrimination is discrimination that individuals practice in their daily lives, usually because they are prejudiced. To many observers, the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in February 2012 was a deadly example of individual discrimination. Martin, a 17-year-old African American, was walking in a gated community in Sanford, Florida, as he returned from a 7-Eleven with a bag of Skittles and some iced tea. An armed neighborhood watch volunteer, George Zimmerman, called 911 and said Martin looked suspicious. Although the 911 operator told Zimmerman not to approach Martin, Zimmerman did so anyway; within minutes Zimmerman shot and killed the unarmed Martin and later claimed self-defense. According to many critics of this incident, Martin’s only “crime” was “walking while black.” As an African American newspaper columnist observed, “For every black man in America, from the millionaire in the corner office to the mechanic in the local garage, the Trayvon Martin tragedy is personal. It could have been me or one of my sons. It could have been any of us” (Robinson, 2012).

Much individual discrimination occurs in the workplace, as sociologist Denise Segura (Segura, 1992) documented when she interviewed 152 Mexican American women working in white-collar jobs at a public university in California. More than 40 percent of the women said they had encountered workplace discrimination based on their ethnicity and/or gender, and they attributed their treatment to stereotypes held by their employers and coworkers. Along with discrimination, they were the targets of condescending comments like “I didn’t know that there were any educated people in Mexico that have a graduate degree.”

Institutional Discrimination

Individual discrimination is important to address, but just as consequential in today’s world is institutional discrimination, or discrimination that pervades the practices of whole institutions, such as housing, medical care, law enforcement, employment, and education. This type of discrimination does not just affect a few isolated individuals, instead, it affects large numbers of individuals simply because of their race, gender, ability, or other group affiliation.

Institutional discrimination often stems from prejudice, as was certainly true in the South during segregation. However, institutions can also discriminate without realizing it. They may make decisions that seem to be racially neutral, but upon close inspection, have a discriminatory effect against people of color. Unfortunately, too often institutional discrimination is a carefully orchestrated plan to target certain groups for discrimination, without appearing to. A particularly egregious example is the so-called War on Drugs, whereby discriminatory enforcement of drug laws resulted in higher arrest and incarceration rates for lower income, urban, communities of color. These communities are not reflective of increased prevalence of drug use, but rather of law enforcement’s targeting of these populations. Institutional discrimination affects the life chances of people of color in many aspects of life today. To illustrate this, we turn to some examples of institutional discrimination that have been the subject of government investigation and scholarly research.

Criminal Justice

Since the declaration of the so called "War on Drugs," the number of incarcerated individuals in the United States (U.S.) has increased tremendously with ~2.3 million individuals reported as incarcerated in 2016, a level higher than any other high-income country. Incarceration disproportionately impacts African American individuals with African American men six times more likely to be incarcerated than non-Hispanic White men and African American women twice as likely to be incarcerated as non-Hispanic white women. In 2016, Black and Latinx individuals represented only 28% of the adult population of the U.S. but accounted for 56% of incarcerated individuals, whereas Whites represented 64% of the adult population but only 30% of incarcerated individuals. These disparities extend into the non-incarcerated community. Forty-four percent of Black women report having a family member imprisoned compared to only 12% of White women. In a 2009 study, African American children born in 1990 had a 25% increased likelihood of having their father go to prison compared to non-Hispanic White children, and that figure rose to a 50% increase if their fathers had not finished high school. Although the disparities are not as striking as with African Americans, other persons of color are also overrepresented in U.S. jail and prison populations with the consequent impact on their families and communities.

This national picture is similarly reflected in my state of California. In 2017, California prisons held over 115,000 individuals with African Americans representing 29% of the male prisoners, despite comprising only 6% of California's male population. The proportion of imprisoned African-American men in California is almost ten-times that of white men, and the population of imprisoned Latino men is almost twice that of white men. Despite similar rates of illicit drug use, African Americans are imprisoned at almost six times the rate of whites for similar infractions; and while African Americans represent only 12.5% of illicit drug users, they account for 29% of drug-related arrests. These data indicate the presence of institutional discrimination in the criminal justice system.

Health Care

People of color have higher rates of disease and illness than whites, due in large part to institutional discrimination based on race and ethnicity. Several studies use hospital records to investigate whether people of color receive optimal medical care, including coronary bypass surgery, angioplasty, and catheterization. After taking the patients’ medical symptoms and needs into account, these studies find that African Americans are much less likely than whites to receive the procedures just listed. This is true when poor blacks are compared to poor whites and also when middle-class blacks are compared to middle-class whites (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). In a novel way of studying race and cardiac care, one study performed an experiment in which several hundred doctors viewed videos of African American and White patients, all of whom, unknown to the doctors, were actors. In the videos, each “patient” complained of identical chest pain and other symptoms. The doctors were then asked to indicate whether they thought the patient needed cardiac catheterization. The African American patients were less likely than the white patients to be recommended for this procedure (Schulman et al., 1999). Why does discrimination like this occur? It is possible, of course, that some doctors are racists and decide that the lives of African Americans just are not worth saving, but it is far more likely that they have unconscious racial biases that somehow affect their medical judgments. Regardless of the reason, the result is the same: African Americans are less likely to receive potentially life-saving cardiac procedures simply because they are black. Institutional discrimination in health care, then, is literally a matter of life and death.

These adverse health outcomes are compounded for people of color when considering the intesectionality between poor health care and incarceration. Incarcerated individuals disproportionately suffer from a range of physical and mental health disorders: HIV is up to seven times more prevalent in prison populations compared to the general population; Hepatitis C is up to 21 times more prevalent. Mental health disorders are up to five times more prevalent in incarcerated populations than the general population, and ~68% of incarcerated individuals suffer from substance abuse disorders with only about 15% receiving adequate treatment. African Americans are disproportionately affected by incarceration, impacting racial disparities in health outcomes. For all of the above reasons, mass incarceration is a significant problem for public health.

Housing

When loan officers review mortgage applications, they consider many factors, including the person’s income, employment, and credit history. The law forbids them to consider race and ethnicity. Yet African Americans and Latinx Americans are more likely than Whites to have their mortgage applications declined (Blank, Venkatachalam, McNeil, & Green, 2005). When confronted with this disparity, many loan officers claim that because members of these groups tend to be poorer than Whites and to have less desirable employment and credit histories, the higher rate of mortgage rejections may be appropriate, albeit unfortunate. To control for this possibility, researchers take these factors into account and in effect compare Whites, African Americans, and Latinx Americans with similar incomes, employment, and credit histories. Some studies are purely statistical, and some involve White, African American, and Latinx individuals who independently visit the same mortgage-lending institutions. Both types of studies find that African Americans and Latinx Americans are still more likely than Whites with similar qualifications to have their mortgage applications rejected (Turner et al., 2002). We will probably never know whether loan officers are consciously basing their decisions on racial prejudice, but their practices still amount to racial and ethnic discrimination whether the loan officers are consciously prejudiced or not.

There is also evidence of banks rejecting mortgage applications for people who wish to live in certain urban, supposedly high-risk neighborhoods, and of insurance companies denying homeowner’s insurance or else charging higher rates for homes in these same neighborhoods. Practices like these that discriminate against houses in certain neighborhoods are called redlining, and they also violate the law (Ezeala-Harrison, Glover, & Shaw-Jackson, 2008). Because the people affected by redlining tend to be people of color, redlining, too, is an example of institutional discrimination.

Mortgage rejections and redlining contribute to another major problem facing people of color: residential segregation. Housing segregation is illegal but is nonetheless widespread because of mortgage rejections and other processes that make it very difficult for people of color to move out of segregated neighborhoods and into unsegregated areas. For example, realtors may tell African American clients that no homes are available in a particular White neighborhood, but then inform White clients of available homes. The now routine posting of housing listings on the Internet might be reducing this form of housing discrimination, but not all homes and apartments are posted, and some are simply sold by word of mouth to avoid certain people learning about them. African Americans in particular remain highly segregated by residence in many cities, much more so than is true for other people of color. The residential segregation of African Americans is so extensive that it has been termed hypersegregation and more generally called American apartheid (Massey & Denton, 1993). The hypersegregation experienced by African Americans cuts them off from the larger society, as many rarely leave their immediate neighborhoods, and results in concentrated poverty, where joblessness, crime, and other problems reign. For several reasons, then, residential segregation is thought to play a major role in the seriousness and persistence of African American poverty (Rothstein, 2012; Stoll, 2008).

Employment

Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned racial discrimination in employment, including hiring, wages, and firing. However, African Americans, Latinx Americans, and Native Americans still have much lower earnings than Whites. It is again difficult to determine whether such discrimination stems from conscious prejudice or from unconscious prejudice on the part of potential employers, but it is racial discrimination nonetheless. A now-classic field experiment documented such discrimination. Sociologist Devah Pager (2003) had young White and African American men apply independently in person for entry-level jobs. They dressed the same and reported similar levels of education and other qualifications. Some applicants also admitted having a criminal record, while other applicants reported no such record. As might be expected, applicants with a criminal record were hired at lower rates than those without a record. However, in striking evidence of racial discrimination in hiring, African American applicants without a criminal record were hired at the same low rate as the white applicants with a criminal record. When we consider intersectionality with incarceration, we see the problem is compounded: incarceration severely diminishes the economic mobility of individuals, reducing their earnings by 40%, and thwarting potential for economic progress. With 1 in 28 (or 2.7 million) U.S. children having an incarcerated parent, the lack of presence and economic support substantially impacts child development.

Contributors and Attributions

Prejudice and Discrimination by, Rice University. Provided by OER Commons. License: CC-BY-NC

Social Problems: Continuity and Change, by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Prejudice, Discrimination, and Stereotyping. By, Fiske, S. T. (2020) . In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/jfkx7nrd License: CC-BY-NC-SA