8.1: Characteristics of Intercultural Conflict

- Page ID

- 47461

Conflict Defined

Conflict is a part of all human relationships (Canary, 2003). Almost any issue can spark conflict—money, time, religion, politics, culture—and almost anyone can get into a conflict. Conflicts are happening all around the world at the personal, societal, political, and international levels. Conflict is not simple and it’s not just a matter of disagreement. According to Wilmot & Hocker (2010), “conflict is an expressed struggle between at least two interdependent parties who perceive incompatible goals, scare resources, and interference from others in achieving their goals. (p. 11)” There are several aspects of conflict that we must consider when pondering this definition and its application to intercultural communication.

Expressed Struggle

Conflict is a communication process that is expressed verbally and nonverbally. Wilmot & Hocker assert that communication creates conflict, communication reflects conflict, and communication is the vehicle for the management of conflict (Wilmot & Hocker, 1998). Often, conflict is easily identified because one party openly and verbally disagrees with the other, but intrapersonal, or internal conflict, may exist for some time before being expressed. An example could be family members avoiding each other because both think, “I don’t want to see them for awhile because of what they did.” The expression of the struggle is often activated by a triggering event which brings the conflict to everyone’s attention.

Interdependent

Parties engaged in expressed struggle do so because they are interdependent. “A person who is not dependent upon another—that is, who has no special interest in what the other does—has no conflict with that other person” (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). In other words, each parties’ choices effect the other because conflict is a mutual activity. Each decision impacts the other. Consider the teenager who chooses to wear an obnoxious or offensive t-shirt before catching the bus. People with no connections to the teen who notice the t-shirt are unlikely to engage in conflict. They have never seen the teen before, and probably won’t again. The ill-advised decision to wear the t-shirt does not impact them, therefore the reason to engage in conflict does not exist. The same scenario involving a teen and their parents would probably turn out differently. Because parents and teens are interdependent, the ill-advised decision to wear an offensive t-shirt could quickly escalate into a power struggle over individual autonomy that leads to harsh words and hurt feelings.

Perception

Parties in conflict have perceptions about their own position and the position of others. Each party may also have a different perception of any given situation. We can anticipate having such differences due to a number of factors that create perceptual filters or cultural frames that influence our responses to the situation. Such influences can be things like culture, race & ethnicity, gender & sexuality, knowledge, impressions of the messenger, and previous experience. These factors and more conspire to form the perceptual filters through which we experience conflict.

Clashes in Goals, Resources, and Behaviors

Conflict arises from differences. It occurs whenever parties disagree over their values, motivations, ideas, or desires. The perception might be that goals are mutually exclusive, or there’s not enough resources to go around, or one party is sabotaging another. When conflict triggers strong feelings, a deep need is typically at the core of the problem. When the legitimacy of the conflicting needs is recognized, it opens pathways to problem-solving.

Characteristics of Intercultural Conflict

Intercultural conflicts are often characterized by more ambiguity, language issues, and the clash of conflict styles than same culture conflict. Intercultural conflict characteristics rest on the principles discussed in greater depth in the foundation chapters. These principles stressed that culture is dynamic and heterogeneous, but learned. Values are manifest in beliefs and behaviors, which lead to the worldviews that guide our perception and navigation through life. Michelle LeBaron (2003) states that “cultures affect the ways we name, frame, blame, and attempt to tame conflicts (p. 3).”

Ambiguity, or the confusion about how to handle or define the conflict, is often present in intercultural conflict because of the multi-layered and heterogeneous nature of culture. What appears on the surface of the conflict may mask what is more deeply hidden below. Verbally indirect, high context cultures, may be reluctant to use words to explore issues of extreme importance than verbally direct, low context cultures. Yet, knowing the general norms of a group does not predict the behavior of a specific member of a group. Dimensions of context, and individual differences can be crucial to understanding intercultural conflict.

Conflict and Communication

Conflict can arise over differences of opinion regarding substantive issues such as Climate Change. On the other hand, they may derive from misunderstandings based on verbal or nonverbal communication tied to cultural norms and values. These can be minor – such as not performing a given greeting appropriately – or more serious – such as perceived rudeness based on how a request has been formulated. Missteps in most forms of nonverbal communication can typically be easily remedied (through observation and imitation) and normally do not pose major sources of conflict. Non-natives in most cases will not be expected to be familiar with established rituals. Most Japanese, for example, will not expect Westerners to have mastered the complexities of bowing behavior, which relies on perceptions of power/prestige differentials unlikely for a foreigner to perceive in the same way as native Japanese. Similarly, non-natives will be forgiven making speaking errors in grammar, vocabulary, or pronunciation. Russians will not expect non-natives to have mastered the complex set of inflections that accompany different grammatical cases. Native Chinese will not expect a mastery of tones. Of course, if the errors interfere with intelligibility, there will be problems in communicative effectiveness. There may be, as we have discussed, some prejudice and possible discrimination against those who do not have full command of a language or who speak with a noticeable foreign accent. Conflict is less likely to come from language mechanics and more likely from mistakes in language pragmatics, most frequently in the area of speech acts, i.e. using language to perform certain actions or to have them performed by others. Native English speakers, for example, will typically qualify requests by prefacing them with verbs such as "would you" or "could you", as in the following:

"Could I please have another cup of tea?"

"Would you pass the ketchup when you're through with it?"

The use of the modal verb "could" or the conditional form "would" is not semantically necessary – they don't add anything to the meaning. They are included as part of the standard way polite requests are formulated in English. Asking the same questions more directly, i.e. "Bring me another cup of tea", would be perceived as abrupt and impolite. Yet, in many cultures, requests to strangers might well be formulated in such a direct way. Languages as different from one another as German and Chinese are both more direct in formulating requests. Non-native English speakers might transfer those formulations from their native language word-for-word into English, leading to a possible perception of rudeness. This is known as pragmatic transfer (See Chapter 4). In another example, Sharifian (2005) illustrates how a particular Persian deep-level cultural value is reflected in language use that can lead to misunderstanding. "Adab va Ehteram", roughly translated as 'courtesy and respect in social relations,' in English, encourages Iranians to constantly place the presence of others at the center of their conceptualizations and monitor their own ways of thinking and talking to make them harmonious with the esteem that they hold for others. (p. 42). To reflect this value, Iranians use the cultural concept known as sharmandegi (sometimes translated as 'being ashamed'). Sharmandegi is rendered in a number of speech acts and can lead to misunderstanding with non-Persian speakers:

Expressing gratitude: 'You really make me ashamed'

Offering goods and services: 'Please help yourself, I'm ashamed, it's not worthy of you.'

Requesting goods and services: 'I'm ashamed, can I beg some minutes of your time.'

Apologizing: 'I'm really ashamed that the noise from the kids didn't let you sleep.'

An important part of how we communicate nonverbally involves paralanguage, not what is said, but how it is said (see Chapter 5). Confusion or conflict can arrive in some cases from differences in tone or intonation. Donal Carbaugh (2005) gives an example, based on work done by John Gumperz:Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

As East Asian workers in a cafeteria in London served English customers, they would ask the customers if they wanted "gravy" [sauce], but asked with falling rather than rising intonation. While this falling contour of sound signaled a question in Hindi, to English ears it sounded like a command. The servers thus were heard by British listeners to be rude and inappropriately bossy, when the server was simply trying to ask, albeit in a Hindi way, a question. This source of conflict, a misperception of another person's actions or intent, here attributing rudeness to a difference in communication style, is one of the more common occurrences in both everyday interactions and in cross-cultural encounters.

Conflict and Ethnocentrism

In our everyday lives, we don't have to think about how to navigate through our own culture. Knowledge of how things work becomes automatic, not requiring any conscious thought. We assume that what we experience as "common-sense" or "normal" is the default human behavior worldwide. When communicating across cultures, this error in thinking can lead us to create expectations for behavior that fail to factor in the cultural context. When expectations are not fulfilled, we may feel vulnerable. That can translate into resentment, anger, and perhaps negative judgment of the host culture. This ethnocentric thinking (see Chapter 7) can easily lead to misunderstanding and conflict. Instead, we need to remember that all cultures have their own values, norms, behaviors, and unique ways of being in the world. Consider the example in the contrast between visiting a pub in Britain and a bar in Spain (see sidebarExample \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Drinking in a Spanish bar or an English pub: not the same

In Spain the norm may be: enter the bar and greet the people there with a general 'Buenos dias', go to the bar; see if there are any friends around; offer to get them drinks; order the drinks at the bar; drink and accept any offers of other drinks from others; when you want to go ask how much you owe, often clarifying with the barman/woman which drinks you are responsible for; make sure you say goodbye to everyone you know and to those you don't with a general 'Hasta luego.' A Spanish man greeting strangers in a bar in England would probably be disappointed in the lack of reciprocity of his greeting. The locals would be suspicious or amused; the Spaniard would feel the locals are perhaps unfriendly. He may be seen as dishonest or evasive if he doesn't offer to pay for the first drink he asks for upon being served that drink. An Englishman entering a Spanish bar may be seen as a little odd or ingenuine if he uses 'please' and 'thank you' all the time. These terms tend to be reserved for asking favors and for having rendered a favor, and are thus not used so 'lightly'.

-Holliday, Hyde & Kullman (2004), p. 199

Conflict Styles

Miscommunication and misunderstanding between people within the same culture can feel overwhelming enough, but when this occurs with people from another culture or co-culture, we may feel a serious sense of stress. Intercultural conflict experts have developed conflict style inventories that help us to understand our own personal tendencies toward dealing with conflict, and the tendencies others may have. Acquiring this knowledge can hopefully help us transform conflicts into meaningful dialog, and become better communicators in the process.

- Direct Approaches are favored by cultures that think conflict is a good thing, and that conflict should be approached directly, because working through conflict results in more solid and stronger relationships. This approach emphasizes using precise language, and articulating issues carefully. The best solution is based on solving for set of criteria that has been agreed upon by both parties beforehand.

- Indirect Approaches on the other hand are favored by cultures that view conflict as destructive for relationships and prefer to deal with conflict indirectly. These cultures think that when people disagree, they should adapt to the consensus of the group rather that engage in conflict. Confrontations are seen as destructive and ineffective. Silence and avoidance are viewed as effective tools to manage conflict. Intermediaries or mediators are used when conflict negotiation is unavoidable, and people who undermine group harmony may face sanctions or ostracism.

- Emotionally Expressive people or cultures are those who value intense displays of emotion during disagreement. Outward displays of emotion are seen as indicating that one really cares and is committed to resolving the conflict. It is thought that it is better to show emotion through expressive nonverbal behavior and words than to keep feelings inside and hidden from the world. Trust is gained through the sharing of emotions, and that sharing is necessary for credibility.

- Emotionally Restrained People or cultures are those who think that disagreements are best discussed in an emotionally calm manner. Emotions are controlled through “internalization” and few, if any, verbal or nonverbal expressions will be displayed. A sensitivity to hurting feelings or protecting the face or honor of the other is paramount. Trust is earned through what is seen as emotional maturity, and that maturity is necessary to appear credible.

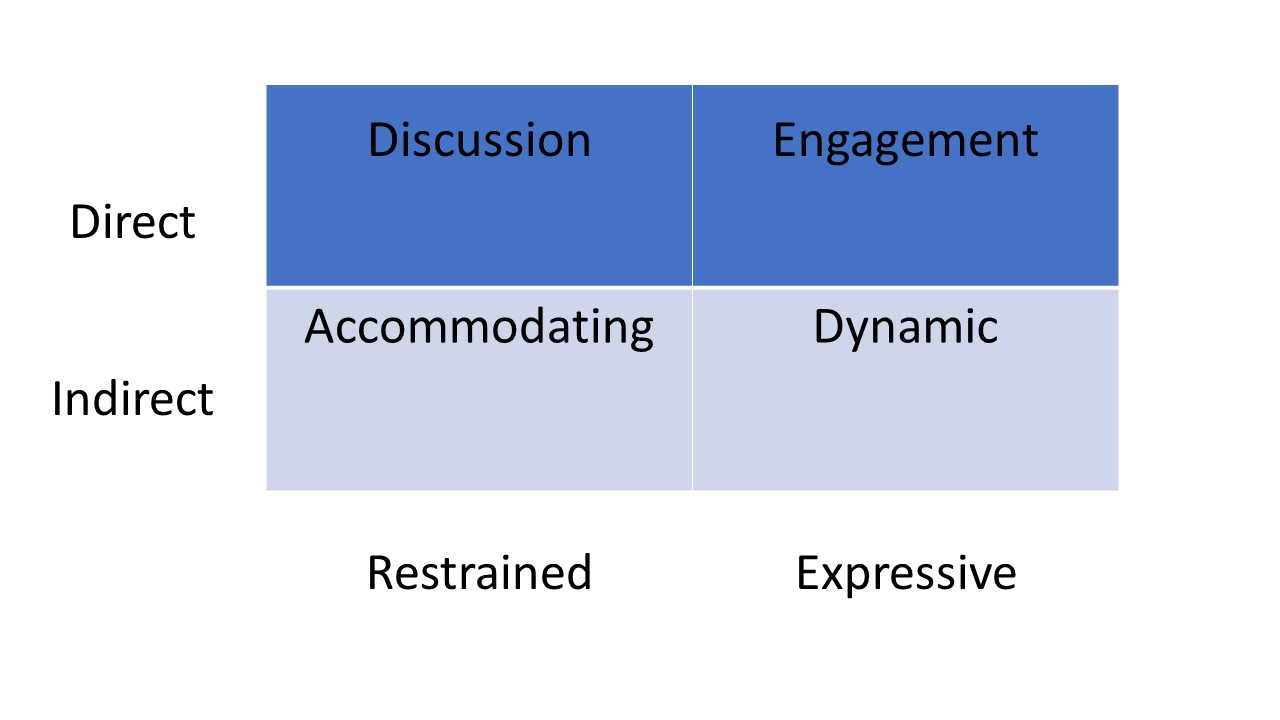

Another way to view conflict styles resolution is through the Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory developed by Mitchell Hammer (2005). According to the theory behind the inventory, disagreements leading to conflict have two dimensions, an affective (emotional) and a cognitive (intellectual or analytical) side. According to Hammer, parties in a conflict experience an emotional response based on the disagreement, its perceived cause, and the threat they see it as posing. How the two parties interact he sees as dependent on how emotionally expressive they tend to be and how direct their communication styles are. This instrument measures people’s approaches to conflict along two different continuums: direct/indirect and expressive/restrained.

The discussion style combines direct and emotionally restrained dimensions. As it is a verbally direct approach, people who use this style are comfortable expressing disagreements. User perceived strengths of this approach are that it confronts problems, explores arguments, and maintains a calm atmosphere during the conflict. The weaknesses perceived by others is that it is difficult to read “read between the lines,” it appears logical but unfeeling, and it can be uncomfortable with emotional arguments. The discussion style can often be found in Northern Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and various co-cultures in the United States.

The engagement style emphasizes a verbally direct and emotionally expressive approach to dealing with conflict. This style views intense verbal and nonverbal expressions of emotion as demonstrating a willingness to resolve the conflict. User perceived strengths to this approach are that it provides detailed explanations, instructions, and information. This style expresses opinions and shows feelings. The weaknesses perceived by others are the lack of concern with the views and feelings of others along with the potential for dominating and rude behavior. Individual viewpoints are not separated from emotion. The engagement style is often used in Mediterranean Europe, Russia, Israel, Latin America, and various co-cultures in the United States.

The accommodating style combines the indirect and emotionally restrained approaches. People who use this approach may send ambiguous message because they believe that by doing so, the conflict will not get out of control. Silence and avoidance are also considered worthy tools. User perceived strengths to this approach are sensitivity to feelings of the other party, control of emotional outburst, and consideration to alternative meaning of ambiguous messages. Weaknesses as perceived by others are difficulty in voicing your own opinion, appearing to be uncommitted or dishonest, and difficulty in providing explanations. Accommodators tend to avoid direct expression of feelings by using intermediaries, friends or relatives who informally act on their behalf when dealing with the conflict. Mediation tends to be used in more formal situations when one person believes that conflict will encourage growth in the relationship. The accommodating style is often used in East Asia, North America and South America.

The dynamic style uses indirect communication along with more emotional expressiveness. These people are comfortable with emotions, but tend to speak in metaphors and often use mediators. Their credibility is grounded in their degree of emotional expressiveness. User perceived strengths to this approach are using third parties to gather information and resolve conflicts, being skilled at observing nonverbal behaviors, and being comfortable with emotional displays. Weaknesses as perceived by others are appearing too emotional, unreasonable, and possibly devious, while rarely getting to the point. The dynamic style is often used in the Middle East, India, Sub-Saharan Africa, and various co-cultures in the United States.

It is important to recognize that people, and cultures, deal with conflict in a variety of ways for a variety of different reasons, and that conflict styles preferred in one culture may not work very well in a different culture. For example, business consultants in the United States advocate for using various versions of the seven-step conflict resolution model. The seven steps are:

- State the Problem. Ask each of the conflicting parties to state their view of the problem as simply and clearly as possible.

- Restate the Problem. Ask each party to restate the problem as they understand the other party to view it.

- Understand the Problem. Each party must agree that the other side understands both ways of looking at the problem.

- Pinpoint the Issue. Zero in on the objective facts.

- Ask for Suggestions. Ask how the problem should be solved.

- Make a Plan.

- Follow up.

A quick review of the previous seven steps betrays its western roots with the unspoken assumption that conflicting individuals will be verbally direct and emotionally restrained, advocates of the discussion style of conflict. As we know from the model above, this may be too direct and/or not emotionally expressive enough to be an effective way to resolve conflicts in other cultures, or with people from other cultures. Lastly, it's important to keep in mind that preferred conflict styles are not static and rigid. People use different conflict styles with different partners and for different issues. Gender, ethnicity, and religion may all influence how we handle conflict. Conflict may even occur over economic, political, and social issues. How such conflicts are managed varies in line with the context and individuals concerned. Communication scholars have identified patterns in conflict management, discussed in the next section.

Contributors and Attributions

Intercultural Communication for the Community College, by Karen Krumrey-Fulks. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Language and Culture in Context: A Primer on Intercultural Communication, by Robert Godwin-Jones. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC

Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies, by No Attribution- Anonymous by request. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA