2.3: Voicing, Resonance and Articulation

- Page ID

- 111894

Classifying Consonants, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

Let’s look more closely at the class of sounds we call consonants. Remember that consonants have some constriction in the vocal tract that obstructs the airflow, either partially or completely. We can classify consonants according to three pieces of information.

The first piece of information we need to know about a consonant is its voicing — is it voiced or voiceless? In the video about how humans produce speech, we felt the difference between voiced and voiceless sounds: for voiced consonants like [z] and [v], the vocal folds vibrate. For voiceless sounds like [s] and [f], the vocal folds are held apart to let air pass through.

The second thing we need to know about consonants is where the obstruction in the vocal tract occurs; we call that the place of articulation.

If we obstruct our vocal tract at the lips, like for the sounds [b] and [p], the place of articulation is bilabial.

The consonants [f] and [v] are made with the top teeth on the bottom lip, so these are called labiodental sounds.

Move your tongue to the ridge above and behind your top teeth and make a [t] or [d]; these are alveolar sounds. Many people also make the sound [s] with the tongue at the alveolar ridge. Even though there is quite a bit of variation in how people make the sound [s], it still gets classified as an alveolar sound.

If you’re making a [s] and move the tongue farther back, not quite to the soft palate, the sound turns into a [ʃ], which is called post-alveolar, meaning it’s a little bit behind the alveolar ridge. You also sometimes see [ʃ] and [ʒ] called “alveo-palatal” or “palato-alveolar” sounds because the place of articulation is between the alveolar ridge and the palate.

The only true palatal sound that English has is [j].

And if you bring the back of your tongue up against the back of the soft palate, the velum, you produce the velar sounds [k] and [ɡ].

Some languages also have uvular and pharyngeal sounds made even farther back in the throat, but English doesn’t have sounds at those places of articulation.

And of course English has a glottal fricative made right at the larynx, the sound [h].

In addition to knowing where the vocal tract is obstructed, to classify consonants we also need to know how the vocal tract is obstructed. This is called the manner of articulation.

If we obstruct the airflow completely, the sound is called a stop. When the airflow is stopped, pressure builds up in the vocal tract and then is released in an burst of air when we release the obstruction. So the other name for stops is plosives. English has two bilabial stops, [p] and [b], two alveolar stops, [t] and [d], and two velar stops [k] and [ɡ].

It’s also possible to obstruct the airflow in the mouth but allow air to flow through the nasal cavity. English has three nasal sounds at those same three places of articulation: the bilabial nasal [m], the alveolar nasal [n], and the velar nasal [ŋ]. Because airflow is blocked in the mouth for these, they are sometimes called nasal stops, in contrast to the plosives which are oral stops.

Instead of blocking airflow completely, it’s possible to hold the articulators close together and allow air to flow turbulently through the small space. Sounds with this kind of turbulence are called fricatives. English has labiodental fricatives [f] and [v], dental fricatives made with the tongue between the teeth, [θ] and [ð], alveolar fricatives [s] and [z], post-alveolar fricatives [ʃ] and [ʒ], and the glottal fricative [h]. Other languages also have fricatives at other places of articulation.

If you bring your articulators close together but let the air flow smoothly, the resulting sound is called an approximant. The glides [j] and [w] are classified as approximants when they behave like consonants. The palatal approximant [j] is made with the tongue towards the palate, and the [w] sound has two places of articulation: the back of the tongue is raised towards the velum and the lips are rounded, so it is called a labial-velar approximant.

The North American English [ɹ] sound is an alveolar approximant with the tongue approaching the alveolar ridge. And if we keep the tongue at the alveolar ridge but allow air to flow along the sides of the tongue, we get the alveolar lateral approximant [l], where the word lateral means “on the side”. The sounds [ɹ] and [l] are also sometimes called “liquids”

If you look at the official IPA chart for consonants, you’ll see that it’s organized in a very useful way. The places of articulation are listed along the top, and they start at the front of the mouth, at the lips, and move gradually backwards to the glottis. And down the left-hand side are listed the manners of articulation. The top of the chart has the manners with the greatest obstruction of the vocal tract, the stops or plosives, and moves gradually down to get to the approximants, which have the least obstruction and therefore greatest airflow.

In Essentials of Linguistics, we concentrate on the sounds of Canadian English, so we don’t pay as much attention to sounds with retroflex, uvular, or pharyngeal places of articulation. You’ll learn more about these if you go on in linguistics. And you probably noticed that there are some other manners of articulation that we haven’t yet talked about.

A trill involves bringing the articulators together and vibrating them rapidly. North American English doesn’t have any trills, but Scottish English often has a trilled [r]. You also hear trills in Spanish, French and Italian.

A flap (or tap) is a very short sound that is a bit like a stop because it has a complete obstruction of the vocal tract, but the obstruction is so short that air pressure doesn’t build up. Most people aren’t aware of the flap but it’s actually quite common in Canadian English. You can hear it in the middle of these words metal and medal. Notice that even though they’re spelled with “t” and “d”, they sound exactly the same when we pronounce them in ordinary speech. If you’re trying hard to be extra clear, you might say [mɛtəl] or [mɛdəl], but ordinarily, that “t” or “d” in the middle of the word just becomes an alveolar flap, where the tongue taps very briefly at the alveolar ridge but doesn’t allow air pressure to build up. You can also hear a flap in the middle of words like middle, water, bottle, kidding, needle. The symbol for the alveolar flap [ɾ] looks a bit like the letter “r” but it represents that flap sound.

When we’re talking about English sounds, we also need to mention affricates. If you start to say the word cheese, you’ll notice that your tongue is in the position to make a [t] sound. But instead of releasing that alveolar stop completely, like you would in the word tease, you release it only partially and turn it into a fricative, [tʃ]. Same thing for the word jam: you start off the sound with the stop [d], and then release the stop but still keep the articulators close together to make a fricative [dʒ]. Affricates aren’t listed on the IPA chart because they’re a double articulation, a combination of a stop followed by a fricative. English has only the two affricates, [tʃ] and [dʒ], but German has a bilabial affricate [pf] and many Slavic languages have the affricates [ts] and [dz].

To sum up, all consonants involve some obstruction in the vocal tract. We classify consonants according to three pieces of information:

- the voicing: is it voiced or voiceless,

- the place of articulation: where is the vocal tract obstructed, and

- the manner of articulation: how is the vocal tract obstructed.

These three pieces of information make up the articulatory description for each speech sound, so we can talk about the voiceless labiodental fricative [f] or the voiced velar stop [ɡ], and so on.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

"Voiceless bilabial stop"

Hint: Look at an IPA chart and the information is there. Also, pronounce that sound on its own, and think about what your articulators are doing.

- The vocal cords don't vibrate, therefore it's voiceless;

- The only articulators involved are your lips; and,

- The air is stopped before it's released all at once.

- Answer

-

"Voiced dental fricative"

Hint: Look at an IPA chart and the information is there. Also, pronounce that sound on its own, and think about what your articulators are doing.

-

- The vocal cords vibrate, therefore it's voiced;

- The articulators involved are your teeth, with the tip of your tongue touching or between your teeth; and,

- The air is released in a continuous stream, with 'friction'.

- Answer

-

"Voiceless post-alveolar fricative"

-

Hint: Look at an IPA chart and the information is there. Also, pronounce that sound on its own, and think about what your articulators are doing.

-

- The vocal cords don't vibrate, therefore it's voiceless;

- The articulator involved is your alveolar ridge, or right behind it, and your tongue is very close to that region; and,

- The air is released in a continuous stream, with 'friction'.

Classifying Vowels, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

Remember that the difference between consonants and vowels is that consonants have some obstruction in the vocal tract, whereas, for vowels, the vocal tract is open and unobstructed, which makes vowel sounds quite sonorous. We can move the body of the tongue up and down in the mouth and move it closer to the back or front of the mouth. We can also round our lips to make the vocal tract even longer.

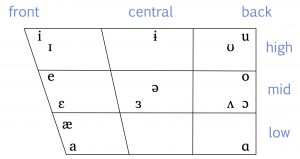

Take a look at the IPA chart for vowels. Instead of a nice rectangle, it’s shaped like a trapezoid. That’s because the chart is meant to correspond in a very direct way with the shape of the mouth and the position of the tongue in the mouth. We classify vowels according to four pieces of information:

The high/mid/low distinction has to do with how high the tongue is in the mouth. Say this list of words:

beet, bit, bait, bet, bat

Now do the same thing, but leave off the “b” and the “t” and just say the vowels. You can feel that your tongue is at the front of your mouth and is moving from high in the mouth for [i] to fairly low in the mouth for [æ].

We can do the same thing at the back of the mouth. Say the words boot, boat.

Now do it again with just the vowels, [u] [o]. Your lips are rounded for both of them, but the tongue is higher for [u] than it is for [o]. The lowest vowel at the back of the mouth is [ɑ]. We don’t round our lips for [ɑ], and we often drop the jaw to move the tongue low and back.

We also classify vowels according to whether the lips are rounded or unrounded. In Canadian English, there are only four vowels that have lip rounding, and they’re all made with the tongue at the back of the mouth:

[u] as in boot

[ʊ] as in book

[o] as in boat

and [ɔ] as in bore

The final piece of information that we use to classify vowels is a little trickier to explain. English makes a distinction between tense and lax vowels, which is a distinction that a lot of other languages don’t have. Tense vowels are made with greater tension in the muscles of the vocal tract than lax vowels. To feel this difference, say the two words sheep and ship. And now make just the vowel sounds, [i], [ɪ]. The [i] sound in sheep and the [ɪ] sound in ship are both produced with the tongue high and front, and without lips rounded. But for [i], the muscles are more tense than for [ɪ]. The same is true for the vowels in late and let, [e] and [ɛ]. And also for the vowels in food and foot, [u] and [ʊ]

It can be hard to feel the physical difference between tense and lax vowels, but the distinction is actually an important one in the mental grammar of English. When we observe single-syllable words, we see a clear pattern in one-syllable words that don’t end with a consonant. There are lots of monosyllabic words with tense vowels as their nucleus, like

day, they, weigh

free, brie, she, tea

do, blue, through, screw

no, toe, blow

But there are no monosyllabic words without a final consonant that have a lax vowel as their nucleus. And if we were to try to make up a new English word, we couldn’t do so. We couldn’t create a new invention and name it a [vɛ] or a [flɪ] or a [mʊ]. These words just can’t exist in English. So the tense/lax distinction is an example of one of those bits of unconscious knowledge we have about our language — even though we’re not consciously aware of which vowels are tense and which ones are lax, our mental grammar still includes this powerful principle that governs how we use our language.

Here’s one more useful hint about tense and lax vowels. When you’re looking at the IPA chart, notice that the symbols for the tense vowels are the ones that look like English letters, while the symbols for the lax vowels are a little more unfamiliar. That can help you remember which is which!

So far, all the vowels we’ve been talking about are simple vowels, where the shape of the articulation stays fairly constant throughout the vowel. In the next unit, we’ll talk about vowels whose shape changes. For simple vowels, linguists pay attention to four pieces of information:

- tongue height,

- tongue backness,

- lip rounding, and

- tenseness.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

"High front unrounded tense vowel"

-

Hint: Look at an IPA chart and the information is there. Also, pronounce that sound on its own, and think about what your articulators are doing.

- The tongue is high in the mouth, and in the front part of the mouth;

- The lips are unrounded; and,

- The tongue is tense, or straight and rigid.

- Answer

-

"Mid front unrounded lax vowel"

-

Hint: Look at an IPA chart and the information is there. Also, pronounce that sound on its own, and think about what your articulators are doing.

- The tongue is of middle height in the mouth, and in the front part of the mouth;

- The lips are unrounded; and,

- The tongue is lax, or relaxed.

- Answer

-

"Low back unrounded tense vowel"

Hint: Look at an IPA chart and the information is there. Also, pronounce that sound on its own, and think about what your articulators are doing.

- The tongue is of low height in the mouth, and in the back part of the mouth;

- The lips are unrounded; and,

- The tongue is tense, or straight and rigid.