2.4: IPA and Charts

- Page ID

- 111895

Describing Speech Sounds: the IPA, from Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

In the first part of this book, we’re concentrating on the sounds of human speech. You might have already noticed that there’s a challenge to talking about speech sounds — English spelling is notoriously messy.

Take a look at these words:

say, weigh, they, rain, flame, lei, café, toupee, ballet

All of them contain the same vowel sound, [e], but the sound is spelled with nine different combinations of letters. Some of them are more common ways than others of spelling the sound [e], but even if we take away the ones that English borrowed from other languages, that still leaves five different ways of spelling one sound. One of the problems is that English has only five letter characters that represent vowels, but more than a dozen different vowel sounds. But it’s not just the vowels that are the problem.

English has the opposite problem as well. Take a look at these words:

cough, tough, bough, through, though

Here we’ve got a sequence of four letters that appear in the same order in the same position in each word, but that sequence of letters is pronounced in five different ways in English. Not only can a single sound be represented by very many different spellings, but even a single spelling is not consistent with the sounds that it represents.

Even one letter can be pronounced in a whole lot of different ways. Look at:

cake, century, ocean, and cello

The letter “c” represents four quite different sounds. Clearly, English spelling is a mess. There are a lot of reasons for why that might be.

The area where English first evolved was first inhabited by people who spoke early forms of Germanic and Celtic dialects. But then Normans invaded and brought all kinds of French and Latin words with their spellings. When the technology to print books was invented, there was influence from Dutch. So even the earliest form of English was influenced by many different languages.

Modern English also borrows words from lots of languages. When we borrow words like cappuccino or champagne, we adapt the pronunciation to fit into English but we often retain the spelling from the original language.

Another factor is that the English spelling system was standardized hundreds of years ago when it became possible to print books. A lot of our standard spellings became consistent when the Authorized Version of the Bible was published in the year 1611. Spelling hasn’t actually changed much since 1611, but English pronunciation sure has, so the way we produce the sounds of English has diverged from how we write the language.

Furthermore, English is spoken all over the world, with many different regional varieties. British English sounds quite different from Canadian English, which is different from Australian English, and Indian English is quite different again, even though all of these varieties are spelled in nearly the same way.

There’s even variation within each speaker of English, depending on the context: the way you speak is going to be different depending on if you’re hanging out with your friends or interviewing for a job or talking on the phone to your grandmother.

The important thing to remember for our purposes is that everyone who knows a language can speak and understand it, and children learn to speak and understand spoken language automatically. So in linguistics, we say that speaking and listening are the primary linguistic skills. Not all languages have writing systems, and not everyone who speaks a language can read or write it, so those skills are secondary.

So here’s the problem: as linguists, we’re primarily interested in speech and listening, but our English writing system is notoriously bad at representing speech sounds accurately. We need some way to be able to refer to particular speech sounds, not to English letters. Fortunately, linguists have developed a useful tool for doing exactly that. It’s called the International Phonetic Alphabet, or IPA. The first version of the IPA was created over 100 years ago, in 1888, and it’s been revised many times over the years. The last revision was fairly recent, in 2015. The most useful thing about the IPA is that, unlike English spelling, there’s no ambiguity about which sound a given symbol refers to. Each symbol represents only one sound, and each sound maps onto only one symbol. Linguists use the IPA to transcribe speech sounds from all languages.

When we use this phonetic alphabet, we’re not writing in the normal sense, we’re putting down a visual representation of sounds, so we call it phonetic transcription. That phonetic transcription gives us a written record of the sounds of spoken language. Here are just a few transcriptions of simple words so you can begin to see how the IPA works.

- snake [snek]

- sugar[ʃʊɡəɹ]

- cake[kek]

- cell[sɛl]

- sell [sɛl]

Notice that some of the IPA symbols look like English letters, and some of them are probably unfamiliar to you. Since some of the IPA symbols look a lot like letters, how can you know if you’re looking at a spelled word or at a phonetic transcription? The notation gives us a clue: the transcriptions all have square brackets around them. Whenever we transcribe speech sounds, we use square brackets to indicate that we’re not using ordinary spelling.

You can learn the IPA symbols for representing the sounds of Canadian English in the next unit. For now, I want you to notice the one-to-one correspondence between sounds and symbols. Look at those first two words: snake and sugar. In English spelling, they both begin with the letter “s”. But in speaking, they begin with two quite different sounds. This IPA symbol [s] always represents the [s] sound, never any other sound, even if those other sounds might be spelled with the letter “s”. The word sugar is spelled with the letter “s” but it doesn’t begin with the [s] sound so we use a different symbol to transcribe it.

So, one IPA symbol always makes the same sound.

Likewise, one sound is always represented by the same IPA symbol.

Look at the word cake. It’s spelled with “c” at the beginning and “k-e” at the end, but both those spellings make the sound [k] so in its transcription, it begins and ends with the symbol for the [k] sound. Likewise, look at those two different words cell and sell. They’re spelled differently, and we know that they have different meanings, but they’re both pronounced the same way, so they’re transcribed using the same IPA symbols.

The reason the IPA is so useful is that it’s unambiguous: each symbol always represents exactly one sound, and each sound is always represented by exactly one symbol. In the next unit, you’ll start to learn the individual IPA symbols that correspond to the sounds of Canadian English.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

"Different"

The reason: When you pronounce the vowel sound in neat, your tongue is high in your mouth, and is represented by [i]. When you pronounce the vowel sound in spread is in the middle of your mouth, height-wise, and is represented by [ɛ].

- Answer

-

"Same"

The reason: The sound at the end of both of those words is an s-like sound, and is represented by [s].

- Answer

-

"Different"

The reason: The first sound of gym is a voiced, post-alveolar africate, and is represented by [dʒ]. The first sound of gum is a voice, velar stop, and is represented by [g].

IPA Symbols and Speech Sounds, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

The following tables give you some sample words so you can start to learn which IPA symbols correspond to which speech sounds. In these tables, the portion of the English word that makes the relevant sound is indicated in boldface type, but remember that English spelling is not always consistent, and your pronunciation of a word might be a little different from someone else’s. These examples are drawn from the pronunciation of mainstream Canadian English. To hear an audio-recording of the sound for each IPA symbol, consult the consonant, vowel, and diphthong charts available here.

The sounds are categorized here according to how they’re produced. You’ll learn more about these categories in units 2.6, 2.7 and 3.2.

Stops

| [p] | peach, apple, cap |

| [b] | bill, above, rib |

| [t] | tall, internal, light |

| [d] | dill, adore, kid |

| [k] | cave, ticket, luck |

| [ɡ] | give, baggage, dig |

Fricatives

| [f] | phone, raffle, leaf |

| [v] | video, lively, love |

| [θ] | thin, author, bath |

| [ð] | there, leather, breathe |

| [s] | celery, passing, bus |

| [z] | zebra, deposit, shoes |

| [ʃ] | shell, ocean, rush |

| [ʒ] | genre, measure, rouge |

| [h] | hill, ahead |

Affricates

| [tʃ] | chip, achieve, ditch |

| [dʒ] | jump, adjoin, bridge |

Nasals

| [m] | mill, hammer, broom |

| [n] | nickel, sunny, spoon |

| [ŋ] | singer, wrong |

Approximants

| [l] | lamb, silly, fall |

| [ɹ] | robot, furry, star |

| [j] | yellow, royal |

| [w] | winter, flower |

Flap

| [ɾ] | butter, pedal (only between vowels when the second syllable is unstressed) |

Front Vowels

| [i] | see, neat, piece |

| [ɪ] | pin, bit, lick |

| [e] | say, place, rain (in spoken Canadian English, [e] becomes [eɪ]) |

| [ɛ] | ten, said, bread |

| [æ] | mad, cat, fan |

| [a] | far, start |

Back Vowels

| [u] | pool, blue |

| [ʊ] | look, good, bush |

| [o] | throw, hole, toe (in spoken Canadian English, [o] becomes [oʊ]) |

| [ʌ] | bus, mud, lunch |

| [ɔ] | store, more, corn |

| [ɑ] | dog, ball, father |

Central Vowels

| [ə] | believe, cinnamon, surround (in an unstressed syllable) |

| [ɨ] | roses, wanted (in an unstressed syllable that is a suffix) |

| [ɚ] | weather, editor (in an unstressed syllable with an r-quality) |

| [ɝ] | bird, fur (in a stressed syllable with an r-quality) |

Diphthongs

| [aɪ] | fly, lie, smile |

| [aʊ] | now, frown, loud |

| [ɔɪ] | boy, spoil, noise |

| [ju] |

cue, few |

You can also use the following charts:

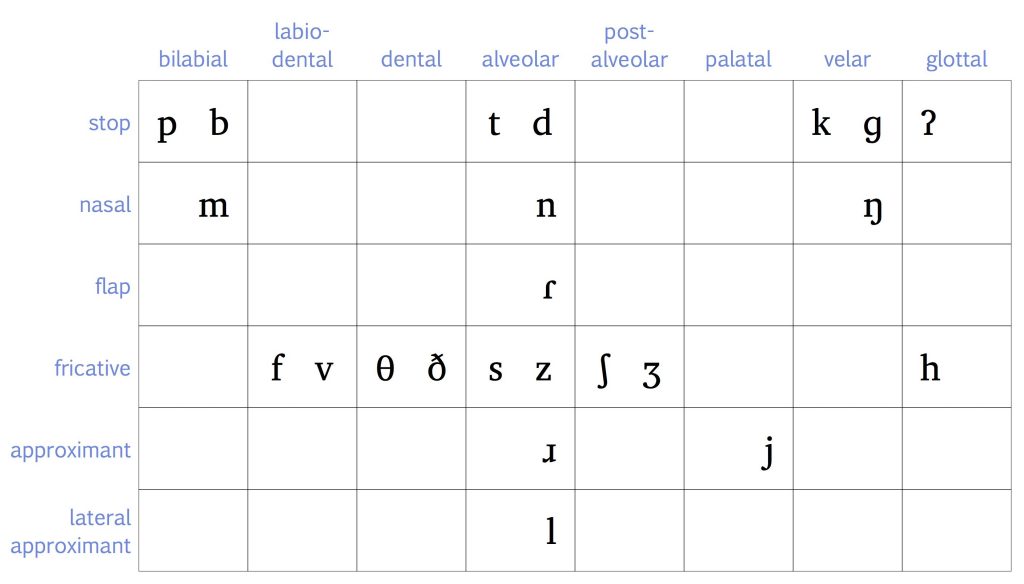

Mainstream American English Consonants

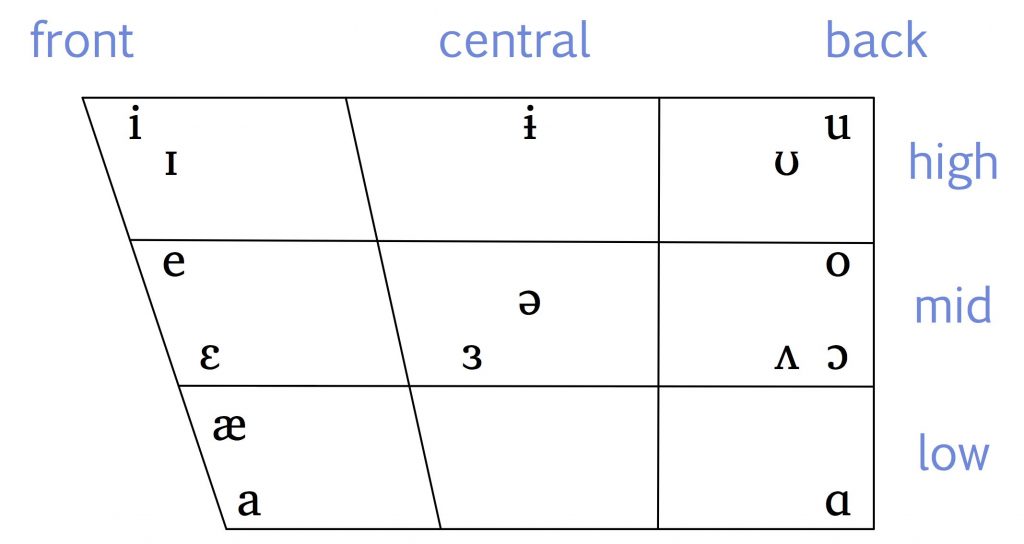

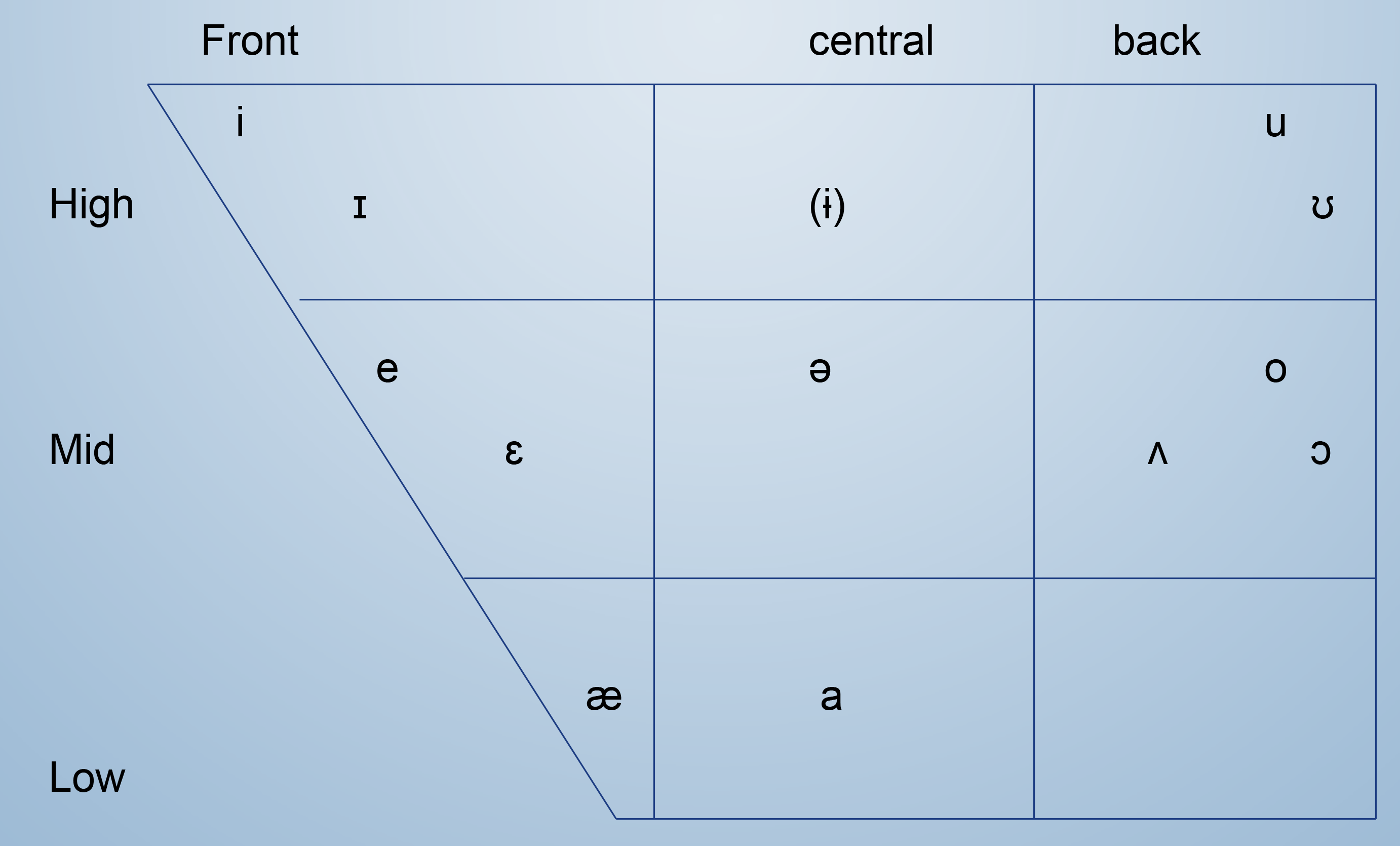

Mainstream American English and Canadian English Vowels

Broad and Narrow Transcription, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Learning to use the IPA to transcribe speech can be very challenging, for many reasons. One reason we’ve already talked about is the challenge of ignoring what we know about how a word is spelled to pay attention to how the word is spoken. Another challenge is simply remembering which symbols correspond to which sounds. The tables in Units 2.4 and 3.2 may seem quite daunting, but the more you practice, the better you’ll get at remembering the IPA symbols.

A challenge that many beginner linguists face is deciding exactly how much detail to include in their IPA transcriptions. For example, if you know that Canadian English speakers tend to diphthongize the mid-tense vowels [e] and [o] in words like say and show, should you transcribe them as the diphthongs [eɪ] and [oʊ]? And the segment [p] in the word apple doesn’t sound quite like the [p] in pear; how should one indicate that? Does the word manager really begin with the same syllable that the word human ends with?

Part of learning to transcribe involves making a decision about exactly how much detail to include in your transcription. If your transcription includes enough information to identify the place and manner of articulation of consonants, the voicing of stops and fricatives, and the tongue and lip position for vowels, this is usually enough information for someone reading your transcription to be able to recognize the words you’ve transcribed. A transcription at this level is called a broad transcription.

But it’s possible to include a great deal more detail in your transcription, to more accurately represent the particulars of accent and dialect and the variations in certain segments. A transcription that includes a lot of phonetic detail is called a narrow transcription. The rest of this chapter discusses the most salient details that would be included in a narrow transcription of the most widespread variety of Canadian English.

Transcribing Vowels in Canadian English, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

(Note: This is an excellent explanation of how to transcribe vowels, and is meant to give you an idea of what to do. The next subsection below will also have how to focus on Mainstream American English, as well as something closer to what we use in California.)

Video Script

Canadian English and American English have a lot in common, but some of the more noticeable differences between them are in how vowels get pronounced. US textbooks often classify this symbol that looks like a lower-case [a] as a low back vowel, but you probably noticed in an earlier section that this book puts [a] in the low front position and lists this character, known as the script [ɑ], in the low back position. What’s the difference between them? To figure this out, let’s look at a pair of words.

How do you pronounce these two words?

I’m a fairly typical speaker of middle-class, middle-aged Canadian English, and for me, these two words are homophones: they sound exactly the same, whether I’m saying, “I caught the ball” or “I slept on a cot“. Caught/cot. So my dialect has what Linguistics calls the “caught/cot merger””. This is pretty typical of Canadian English, but not of many other varieties of English.

In many varieties of US English, the past tense of the verb catch is pronounced with the low-back [ɑ] like mine, but the noun uses the low front [a], [kʰat]. I like to think of this low front vowel as the Chicago White Sox vowel, because it’s very typical of Chicago English, where the south-side baseball team is known as the [saks].

And in many of the varieties of English spoken in the UK, the past tense of catch has a mid-back rounded vowel, [kʰɔt], while the noun version has the low back vowel [kʰɑt].

Since this book concentrates on Canadian English, I’m going to suggest the following convention. When transcribing Canadian English, use the low back vowel that we represent with the script a [ɑ] for the simple vowel in words like father, box, and log.

The low-front [a] doesn’t usually appear in Canadian English as a simple vowel. It shows up in the major diphthongs, [aɪ] like in fly, and [aʊ] as in brown, and it turns up before an [ɹ] as in car or farther.

And this mid-back rounded vowel also doesn’t show up as a simple vowel in Canadian English. It appears in the diphthong [ɔɪ] like in coin, and before [ɹ] like fork or short.

Note that this convention that I’m suggesting does over-simplify the variation that exists in the real world, but that’s ok at this introductory level.

With the low vowels taken care of, let’s talk about the mid and central vowels. Think about these two words, funny and phonetics. They start with almost the same syllable, don’t they? But there’s one important difference. In funny, the stress is on the first syllable, while in phonetics, the second syllable is stressed. This has consequences for the vowel in the nucleus of each syllable.

Remember that we talked about syllable stress in an earlier section. Stressed syllables are more prominent than unstressed syllables. They’re louder, longer, and higher in pitch. So stressed syllables get pronounced with full vowels. In the word funny, the first syllable has this mid-back unrounded vowel that we represent with the wedge symbol [ʌ]. But when a syllable is unstressed, it gets reduced — it’s shorter and quieter. That means that speakers pronounce the vowel with the mid-central reduced vowel that has the funny name schwa [ə] and looks like an upside-down e.

You can hear this stress difference between the “uh” sound in bun and the first syllable of banana, and between the first syllables of apple and apply. So being able to recognize stress is important in producing an accurate transcription.

Speaking of unstressed syllables, in an earlier section we talked about what happens when a syllable is so reduced that the vowel nucleus disappears entirely and the sonorant consonant from the coda becomes a vowel. This is another oversimplification, but at this intro level let’s treat a syllable with a reduced nucleus as equivalent to one that has a syllabic consonant as its nucleus. So we’ll consider these transcriptions on the left as equivalent to the ones on the right.

Many words in English end with an unstressed -er syllable, so [ɹ] is maybe the sonorant that becomes syllabic the most frequently. It just so happens that the IPA also has a way of transcribing a vowel that takes on a rhotic, or r-like quality. So in addition to considering the schwa-r transcription as equivalent to the syllabic-r, we’ll also consider the rhotic-schwa transcription to be equivalent. Again, this is an oversimplification, but it makes sense for when you’re first learning to do IPA transcription.

Now, you already know that schwa is a reduced vowel that only appears in unstressed syllables, so what about when a word has that “er” sound in a stressed syllable, like in bird? We’ll use a different symbol to represent the stressed one: this is the mid-central, unreduced vowel. Notice that looks a lot like the symbol for the mid-front [ɛ] vowel, but it faces the opposite direction!

The only place this vowel shows up in Canadian English is when it’s rhotic, that is, in a stressed syllable with an [ɹ] in the coda. You can hear the difference if you compare the word bird with the second, unstressed syllable in amber.

There’s one more central vowel we need to pay attention to, and that’s the high central vowel that looks like a little crossed-out lower-case letter i. Again, it has a very predictable distribution in Canadian English. We’ll use it only in unstressed syllables where the syllable is a suffix. For example, the final syllable in heated and excited is a past-tense suffix, and the final syllable in horses and quizzes is a plural suffix, so we’ll transcribe them all with this high central vowel.

That’s a lot of details! But paying attention to these subtle differences will develop your phonetic listening skills, and your transcription skills.

Check Yourself

In Mainstream American English, what vowel is in the nucleus of the first syllable of the word delay?

- [e]

- [ɜ]

- [ɨ]

- [ə]

- Answer

-

"[ə]"

Hint: When you pronounce that vowel, your tongue is in the middle of the mouth, somewhat towards the back.

In Mainstream American English, what vowel is in the nucleus of the last syllable of the word ended?

- [ɛ]

- [ə]

- [ɨ]

- [ɜ]

- Answer

-

"[ɨ] for some; [ə] for others"

Hint: When you pronounce that vowel, your tongue is in the central part of your mouth. For many American dialects, it's in the same place as the previous example; for others, especially in the Western U.S., the vowel is a bit higher.

In Mainstream American English, what vowel is in the nucleus of the first syllable of the word dusty?

- [ə]

- [ʊ]

- [ʌ]

- [u]

- Answer

-

"[ʌ]"

Hint: When you pronounce that vowel, your tongue is towards the back of the mouth, and about midway up in height. Your tongue is also relaxed

IPA and Charts, from Sarah Harmon

Video Script

Catherine Anderson does an amazing job in describing why we have IPA, the International Phonetic Alphabet, in the first place and describing the sounds. Of course, she's Canadian and so the charts that she used are all Canadian Standard English. I figured it would be important to bring in the Mainstream American English, just so that you have a little bit of context.

| Bilabial

|

Labiodental

|

Dental

|

Alveolar

|

Post-Alveolar

|

Palatal

|

Velar

|

Glottal

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop

|

p b

|

t d

|

k g

|

Ɂ

|

||||

| Nasal

|

m

|

n

|

(ɲ)

|

ŋ

|

||||

| Fricative

|

f v

|

Θ ð

|

s z

|

ʃ ʒ

|

(x)

|

h

|

||

| Affricate

|

ʧ dʒ

|

|||||||

| Lateral

|

l

|

L

|

||||||

| Rhotic

|

ɾ (r) ɹ

|

|||||||

| Glide, Semi-cons.

|

ʍ w

|

j

|

ʍ w

|

One thing to note is that for the consonants are going to be identical; Canadian English, American English, it doesn't matter. The constants are exactly the same. What is interesting is that I would argue in Mainstream American English—or Standard American English, if you wish, but that phrasing is going out of style and for a number of reasons—has added a few other sounds. It's exactly because of its proximity to Spanish; we have so many native Spanish speakers here in the United States. In major population areas like the Bay Area, and most of California, you can argue certainly the Phoenix area, and most of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and throughout the entirety of the US, there are certain sounds that are starting to migrate in as official sounds of English. For example, that piece of flatbread that you have with Mexican food, you don't call it a 'tortila'; you call it a ‘tortilla’. Now, you may not go full Spanish pronunciation of 'tortilla', but you certainly don't say 'tortila'. A really common chili pepper that is used in a lot of cooking, including Mexican cooking, is not a 'jalapano'. Nobody calls it a 'jalapano'. You at the very least say ‘jalapeño’ and you do that [ɲ] to go with it. Sometimes you do a velar [x] to go with it, because in Spanish, of course, it is a 'jalapeño'.

There are certain sounds that have started to creep into Mainstream American English, and those are the ones you see in parentheses. You have the palatal [ɲ]; for example, I teach not at Canada College but at Cañada College, and anybody who's in the San Francisco Bay Area, especially in San Mateo County, you know that is Cañada College; you don't call it Canada College. That, for example, that have that we here in jalapeño in the Spanish pronunciation of that term, some people do actually use that velar fricative of instead of the glottal [h] sound. The trill [r] that you hear in Spanish, and in so many other languages, is also starting to creep in; it's not entirely they're not as entrenched just say that palatal nasal but certainly the rest of them are there.

As far as whether you call these glides, semi consonants, or approximates, they're all kind of the same thing. If you get into hardcore phonetics, then you start understanding the differences between those terms, but for here I will call them a glide or an approximate, and she tends to call them an approximate. Sometimes you will see them as semi consonants. They're all interchangeable terms as far as you're concerned. Of course, both lateral and rhotic approximates tend to be separated out on most IPA charts. I don't think she did it in hers, but I am doing it in mine, so that you can see.

In English, whether it's Canadian English American English or just about any other English, the consonants are pretty much the same. What is different is the vowels. So, you had the Canadian English vowel chart above in the Catherine Anderson work, this is the Mainstream American English sound chart for the vowels.

The barred 'i' [ɨ] that central high vowel that it is in parentheses, because not all dialects have it, although it is becoming more common west of the Mississippi River. But pretty much all of these sounds are in existence in some way, shape or form in Mainstream American English and in most American English dialects, though there is some difference, and we'll come back to that when we talk about sociolinguistics and different dialects.

What you can see here is that there is a slew of English vowel sounds. Its enormous. Most languages don't have that many sounds; they might have typically five to seven. With English, it depends on what dialect you're talking about; English can have anywhere from seven to 14 different vowel sounds. Those are just the single vowels, not even counting the diphthongs, triphthongs, quadrathongs; those would be the drawls that you see and hear.

This is a real issue when we're talking about English. For those of you for whom English is not your native language and is still a language you are acquiring, this no doubt is the hardest part about the English sound system. And if American English was not the first dialect of English that you came across, it gets complicated even more. Those would be the big differences between the various dialects of English. We'll come back to this more later when we get to sociolinguistics.