5.3: Phrase Structure Rules, X-Bar Theory, and Constituency

- Page ID

- 112736

Tree Diagrams, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

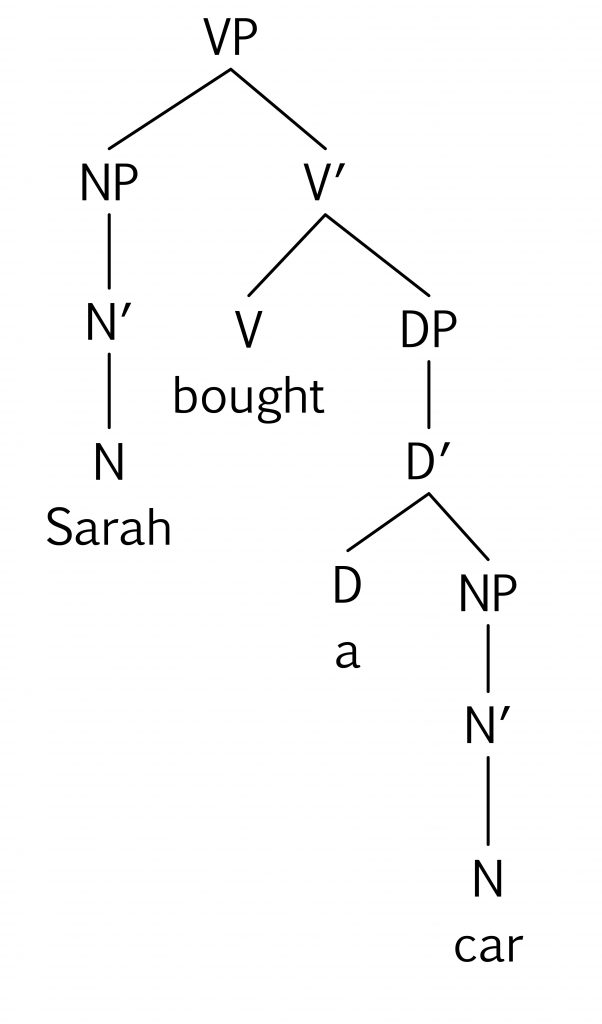

We’re about to start looking into how sentences are organized in our mental grammar. Before we do that, we need to be familiar with a particular kind of notation called a tree diagram. We’ll see that, within each sentence, words are grouped into phrases. Phrases can be grouped together to form other phrases, and to form sentences. We use tree diagrams to depict this organization. They’re called tree diagrams because they have lots of branches: each of these little lines that join things in the diagram is a branch. Within a tree diagram, we can talk about the relationships between different parts of the tree.

Every place where branches join together is called a node. Each node corresponds to a set of words that act together as a unit called a constituent, which we’ll talk about later in this chapter.

Each branch connects one node to another. The higher node is called the parent and the lower one is the child. A parent can have more than one child, but each child has only one parent. And, as you might expect, if two child nodes have the same parent, then we say that they’re siblings to each other. (Just so you know, most linguistics textbooks call these nodes “mother, daughter and sister” nodes, but we’re using non-gendered terms in this book.)

If a node has no children, we call it a terminal node.

Having this vocabulary for tree diagrams will allow us to talk about the syntactic relationships between the parts of sentences in our mental grammar.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

"V and NP are sisters."

The reason: They are on the same level, both coming off of a mother node, V'.

- Answer

-

"NP and V are not related in any of these three ways."

The reason: There are too many steps/nodes separating them.

- Answer

-

"T’."

The reason: They are on the same level, both coming off of a mother node, TP.

X-Bar Phrase Structure, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

We’re starting to look at how our minds organize sentences. We’ll see that within each sentence, our mental grammar groups words together into phrases and phrases into sentences. We saw in the last unit how we can use tree diagrams to show these relationships between words, phrases and sentences.

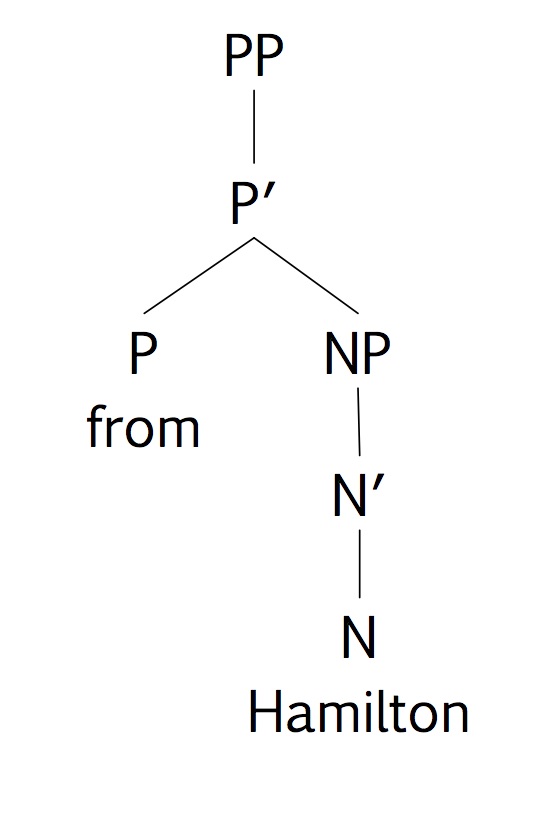

The theory of syntax that we’re working within this class is called X-bar theory. X-bar theory makes the claim that every single phrase in every single sentence in the mental grammar of every single human language, has the same core organization. Here’s a tree diagram that shows us that basic organization. Let’s look at it more closely. According to x-bar theory, every phrase has a head. The head is the terminal node of the phrase. It’s the node that has no daughters. Whatever category the head is determines the category of the phrase. So if the head is a Noun, then our phrase is a Noun Phrase, abbreviated NP. If the head is a verb (V) then the phrase is a verb phrase (VP). And likewise, if the head is a preposition (P), then the phrase is a preposition phrase (PP), and Adjective Phrases (AP) have Adjectives as their heads.

So the bottom-most level of this structure is called the head level, and the top level is called the phrase level. What about the middle level of the structure? Syntacticians love to give funny names to parts of the mental grammar, and this middle level of a phrase structure is called the bar level; that’s where the theory gets its name: X-bar theory.

So if every phrase in every sentence in every language has this structure, then it must be the case that every phrase has a head. But you’ll notice in this diagram that these other two pieces, the specifier and the complement, which we haven’t talked about yet, are in parentheses. That’s to show that they’re optional — they might not necessarily be in every phrase. If they’re optional, that means that it should be possible to have a phrase that consists of just a single head — and if we observe some grammaticality judgments, we can think of phrases and even whole sentences that seem to contain a head and nothing else. We could have a noun phrase that consists of a single noun — Coffee? or Spiderman! We could have verb phrase that has nothing in it but a verb, like Stop! or Run! Or an adjective phrase might consist of only a single adjective, like Nice… or Excellent!

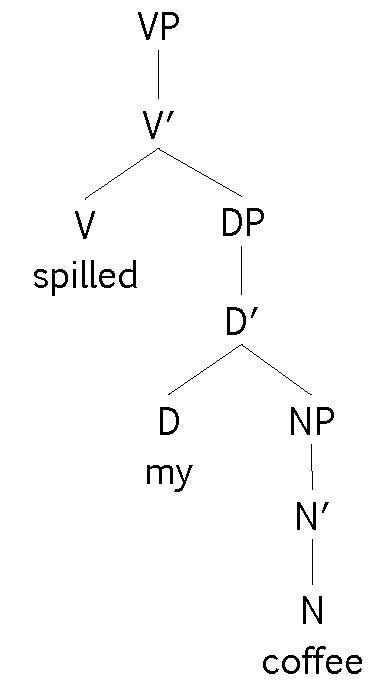

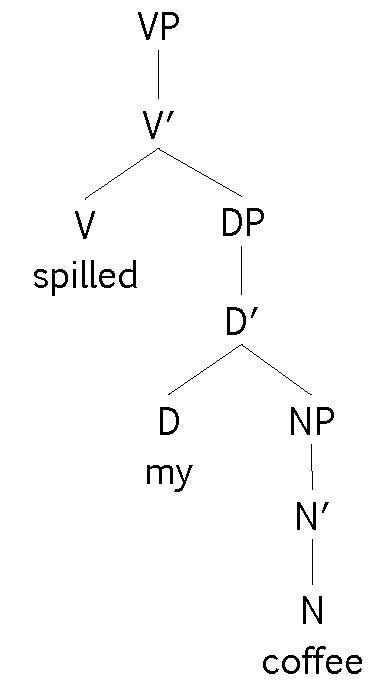

But X-bar theory proposes that phrases can have more in them than just ahead. A phrase might optionally have another phrase inside it in a position that is sister to the head and daughter to the bar level. If there’s a phrase in that position, it’s called the complement. The most common kinds of head-complement relationship we see are a verb taking an object or a preposition taking an object. Let’s look at some examples. Here we’ve got a verb phrase, with the verb drank as its head. That head has the noun phrase coffee as its sister. The NP coffee is sister to the verb head and daughter of the V-bar node so it is a complement of the verb.

Here’s another example that has the same structure, but a different category. The head of this phrase is the preposition near, so the phrase is a preposition phrase. The complement of the preposition is the noun phrase campus and the whole phrase is near campus. Try to think of some other examples of verbs and prepositions that take noun phrases as their complements.

The other common place we see a head-complement relationship is between a determiner and a noun. In phrases like my sister, those shoes, and the weather, the determiner is a head that takes an NP complement.

X-bar theory also proposes that phrase can have a specifier. A specifier is a phrase that is sister to the bar-level and daughter to the phrase level. The most common job for specifiers is as the subjects of sentences, so we’ll look at those in another unit.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

"Complement."

The reason: It's the complement of the V, both under the mother node of V'.

- Answer

-

"Head."

The reason: It's the D in the DP.

- Answer

-

"Complement."

The reason: It's the necessary element and complement of a P.

Constituents, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

We’ve started to use tree diagrams to represent how phrases are organized in our mental grammar. And we’re using the tree diagram notation to represent every single phrase as having X-bar structure. But so far I’ve just asked you to believe me about X-bar structure: I’ve told you that this is what the theory claims, but we haven’t yet talked about any evidence that our mental grammar really is organized into phrases that have X-bar structure. This unit shows some of the linguistic evidence that phrases have some reality in the mental grammar.

When we draw a tree diagram, we’re making a claim about how a sentence or phrase is organized in our mind. Every time we draw two or more branches coming together at a node, we’re making the claim that the node corresponds to a unit. In other words, all the daughters of that node behave together as a unit. Some of these nodes are at the phrase level, and some of them are at the bar-level. The more generic term for a group of words that act together to form a unit is a constituent.

So what’s our evidence that constituents exist in our minds? Within a given sentence, how can we tell if a given string of words acts as a unit? Here again is where we rely on observing our grammaticality judgments, using a few simple tools.

Replacement Test

Here’s a simple sentence:

The students saw their friends after class.

Let’s consider the string of words their friends. Because you’ve already started to practice drawing trees, you probably have an instinct that this is a noun phrase. But if you’re going to claim that it’s a constituent, it would be nice to have some evidence for that claim. One piece of evidence is that we can replace this set of words. Take the pronoun them and replace the string of words we’re investigating:

The students saw their friends after class.

The students saw them after class.

Then we ask ourselves whether the resulting sentence is grammatical. Replacing their friends with them does indeed leave us with a grammatical sentence, which is one piece of evidence that their friends is a constituent.

Let’s test another chunk of this sentence. Let’s try the string of words after class. If we replace that set of words with the word then:

The students saw their friends after class.

The students saw their friends then.

And when we observe our grammaticality judgment, it turns out that this replacement is also grammatical. That’s some evidence that words after class behave together as a constituent in this sentence.

We can do the same thing with the string the students. Replace that string with the pronoun they:

The students saw their friends after class.

They saw their friends after class.

And observe our grammaticality judgment, and we find evidence that the students is a constituent as well.

What happens if we try to replace a string of words that isn’t a constituent?

The students saw their friends after class.

*The they friends after class.

*The did friends after class.

*The then friends after class.

*The them friends after class.

We can try lots of replacements, but when we ask ourselves whether the result is grammatical, the answer is No. There doesn’t seem to be anything that can replace the string of words students saw their. The fact that nothing can replace that string of words suggests that students saw their is not a constituent in this sentence.

At this point, you’re probably wondering how you know what you can use as a replacement. Here are some handy tips:

- Noun Phrases can be replaced with Pronouns (it, them, they).

- Verb Phrases can be replaced with do or do so (or did, does, doing).

- Some Preposition Phrases (but not all) can be replaced with then or there.

- Adjective Phrases can be replaced with something that you know to be an adjective, such as happy.

Let’s see how this replacement tool works for a verb phrase. We’ll go back to our sentence and look for the verb, saw. Let’s test this set of words: saw their friends. Since saw is the past tense of see, we’ll try replacing it with did, the past tense of do, and observe our grammaticality judgment.

The students saw their friends after class.

The students did after class.

This replacement is grammatical, so that provides us with some evidence that the set of words saw their friends is indeed a constituent.

You can use this evidence as you’re drawing trees. If you can’t quite figure out which groups of words go together into certain phrases, you can try replacing different chunks of the sentence. The parts that allow themselves to be replaced, that is, the parts that can be replaced and still leave a grammatical sentence are constituents, and those parts will be joined under one node.

You can also use this evidence when you’re trying to figure out what category a certain phrase is: If you can replace it with a pronoun, then you’ve got a noun phrase and you can look for the noun as the head. If you can replace it with do or do so, then you’ve got a verb phrase which will have a verb as its head. Then and there are a little less reliable because they sometimes replace PPs or APs, but you’ll be able to tell the difference between prepositions and adjectives because prepositions usually have complements and adjectives don’t.

Movement Test

Replacement is not the only tool we have for checking if a set of words is a constituent. Some constituents can be moved to somewhere else in the sentence without changing its meaning or its grammaticality. Preposition Phrases are especially good at being moved. Look at this sentence:

Nimra bought a top from that strange little shop.

Let’s start by targeting the last string of words by moving it to the beginning. Move the string of words then ask yourself whether the resulting sentence is grammatical.

Nimra bought a top from that strange little shop.

From that strange little shop Nimra bought a top.

Yes, it is. Standing here in isolation, the sentence might sound a little unnatural, but we can imagine a context where it would be fine, such as, “At the department store, she bought socks, at the pharmacy she bought some toothpaste, and at that strange little shop, she bought a top.” On the other hand, if we target a smaller string of words:

Nimra bought a top from that strange little shop.

*From that strange, Nimra bought a top little shop.

If we try to move that string to the beginning of the sentence, the result is a total disaster. The fact that the resulting sentence is totally ungrammatical gives us evidence that the string of words from that strange is not a constituent in this sentence.

Cleft Test

There’s a version of the movement tool that can be useful for other kinds of phrases. It’s called Clefting. A cleft is a kind of sentence that has the form:

It was ____ that …

To use the cleft test, we take the string of words that we’re investigating and put it after the words It was, then leave the remaining parts of the sentence to follow the word that. Let’s try it for the phrases we’ve already shown to be constituents.

Nimra bought a top from that strange little shop.

It was from that strange little shop that Nimra bought a top.

The students saw their friends after class.

It was their friends that the students saw after class.

It was after class that the students saw their friends.

And let’s try the cleft test on another new sentence.

Rhea’s sister baked these delicious cookies.

It was these delicious cookies that Rhea’s sister baked.

It was Rhea’s sister that baked these delicious cookies.

The cleft test shows us that the string of words these delicious cookies are a constituent, and that the words Rhea’s sister are a constituent. But look what happens if we apply the cleft test to another string of words:

Rhea’s sister baked these delicious cookies.

*It was sister baked that Rhea’s these delicious cookies.

Rhea’s sister baked these delicious cookies.

*It was these delicious that Rhea’s sister baked cookies.

Rhea’s sister baked these delicious cookies.

*It was cookies that Rhea’s sister baked these delicious.

All of these applications of the cleft test result in totally ungrammatical sentences, which gives us evidence that those underlined strings of words are not constituents in this sentence.

Answers to Questions

If a string of words is a constituent, it’s usually grammatical for it to stand alone as the answer to a question based on the sentence.

Rhea’s sister baked these delicious cookies.

What did Rhea’s sister bake? These delicious cookies.

Who baked these delicious cookies? Rhea’s sister.

The answer-to-questions test can also help us identify a verb phrase using do-replacement:

Who baked these delicious cookies? Rhea’s sister did.

Notice that in the answer, “Rhea’s sister did”, the word did automatically replaces the verb phrase baked these delicious cookies.

Again, if a string of words is not a constituent, then it is unlikely to be grammatical as the answer to a question. In fact, it’s difficult to even form the right kind of question:

What did Rhea’s sister bake cookies? *these delicious

Who of Rhea’s these delicious cookies? *sister baked

Remember that tree diagrams are a notation that linguists use to depict how phrases and sentences are organized in our mental grammar. We can’t observe mental grammar, so observing how words behave is how we make inferences about the mental grammar. These four tests are tools that we have for observing how words behave in sentences. If we discover a string of words that passes these tests, then we know that the phrase is a constituent, and therefore there should be one node that is the mother to that entire string of words in our tree diagram.

Not every constituent will pass every test, but if you’ve found that it passes two of the four tests, then you can be confident that the string is actually a constituent. When you’re drawing trees, use these tests as a check every time you draw a mother node.

Sentences are Phrases, from Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

We’ve been developing a model for how the mind generates sentences. Our idea is that we draw words, morphemes, and morphosyntactic features from the mental lexicon, and then the operation MERGE organizes all these things and into an x-bar structure. And the theory makes the quite powerful claim that every phrase in every sentence is organized in an x-bar structure, with a head, a bar-level and a phrase level.

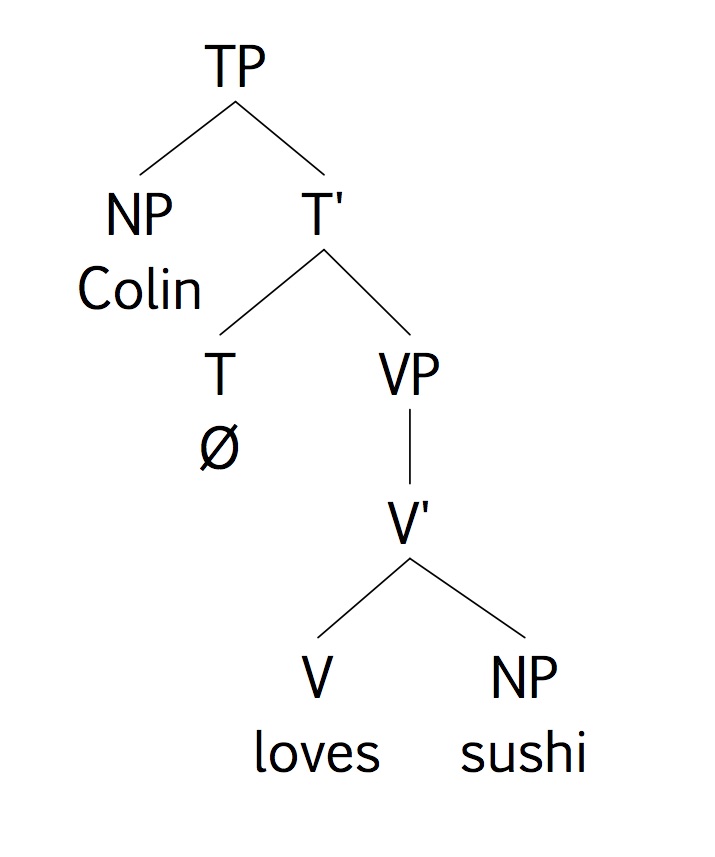

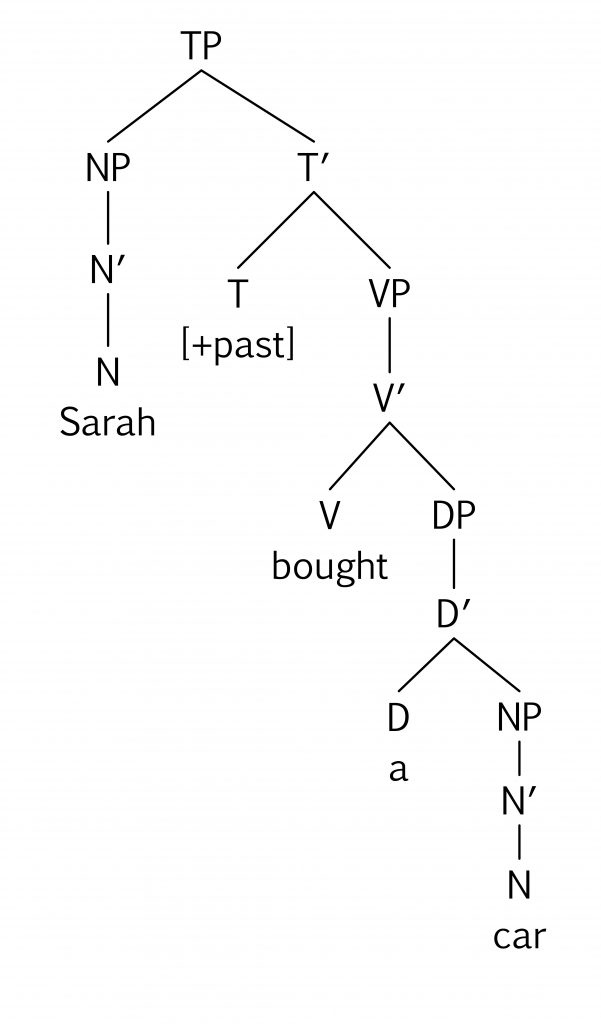

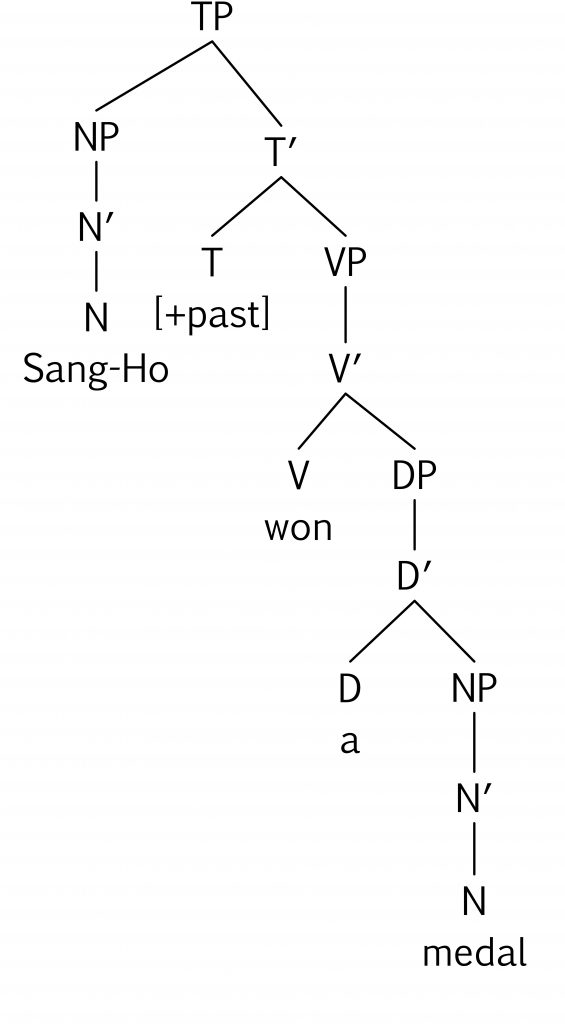

So it’s fairly easy to understand that verb phrases have verb heads, and preposition phrases have preposition heads. But what kind of phrases are sentences? If we look carefully, we can observe that every sentence includes one and only one tense feature, which occupies a head position that we label as T, for Tense. And of course, where there is a head there are also the bar level and the phrase level. So a sentence is a T-phrase.

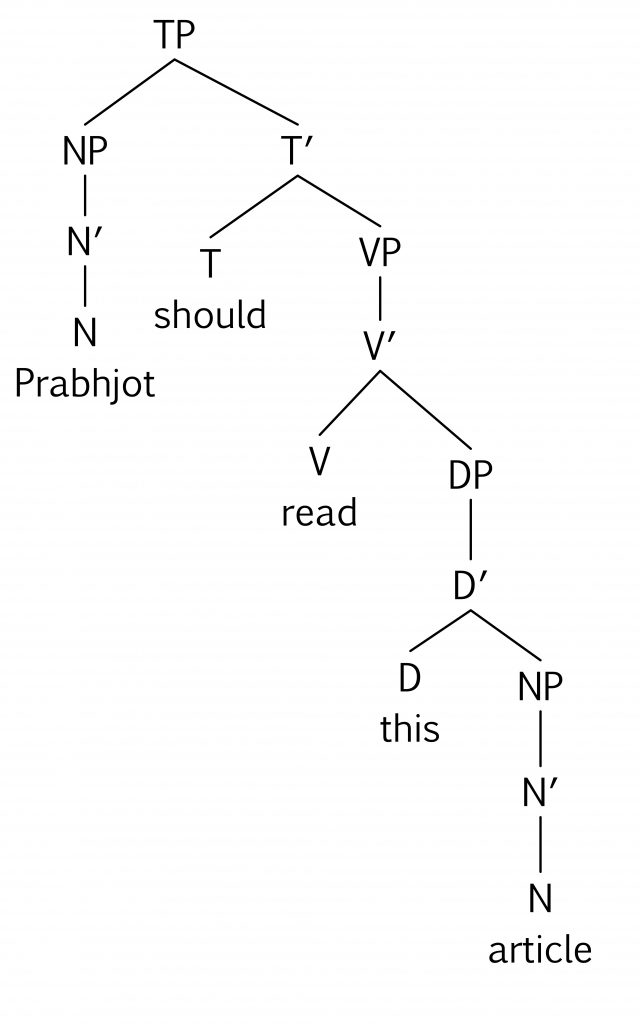

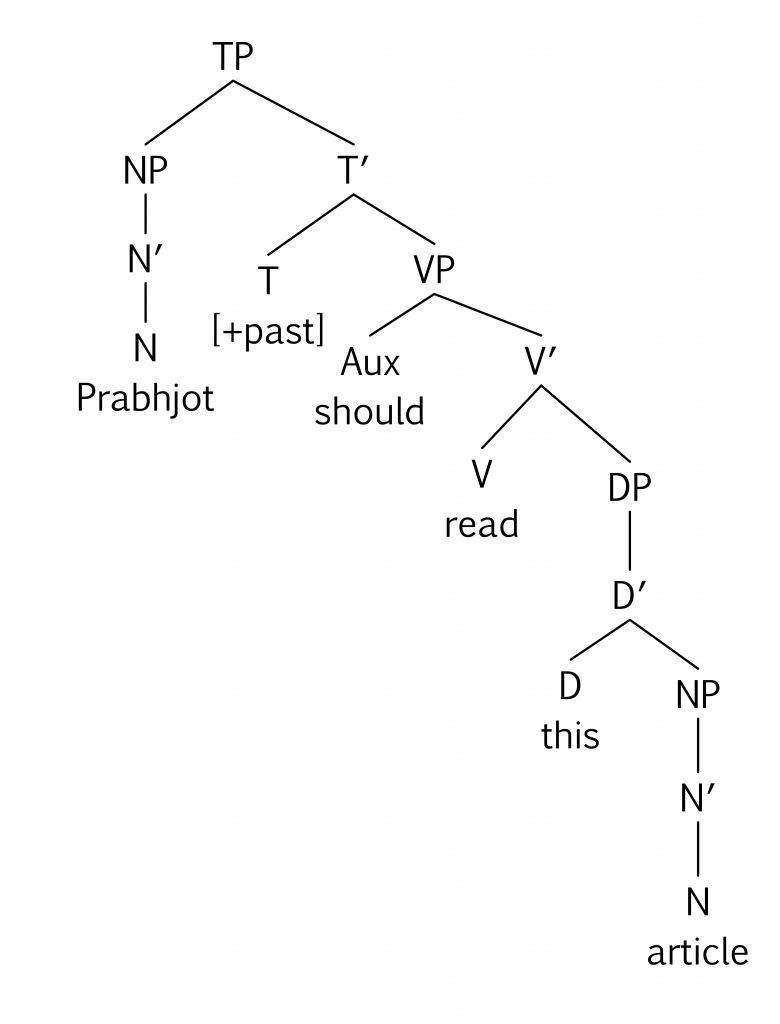

Let’s see how this works in a fairly simple sentence. “Alex should try yoga.” We already know how to depict verb phrases. The verb try is a transitive verb, and the NP yoga is its complement. The modal auxiliary should occupies the T head position. A T head always takes a VP as its complement. So every sentence that we see from here on will have a T head with a VP complement.

Whenever there’s a head, there’s also a bar-level and a phrase level. And the last phrase we have left in the sentence is the noun phrase Alex. It’s the subject of the sentence. We said that specifiers are kind of special, and the subject is the most special of all. The Specifier of TP is the position for the phrase, usually a noun phrase, that’s the subject of the sentence. Subjects go in SpecTP.

To sum that all up, every sentence is a T-phrase. The T-head of the T-phrase takes a VP as its complement. And the specifier of TP is a noun phrase, and the name for the noun phrase that occupies that position is the subject of the sentence.

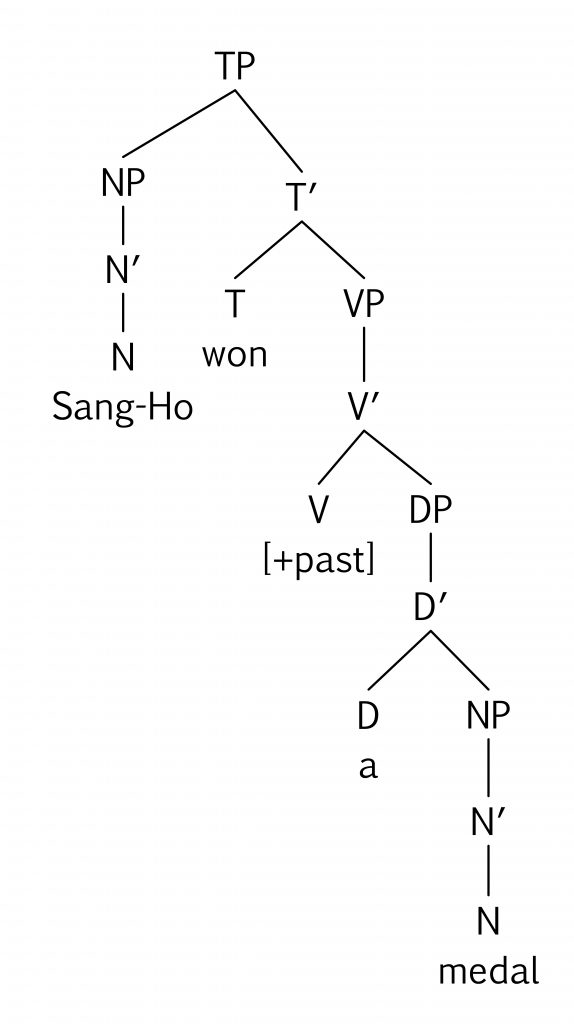

What kinds of things can occupy the T-head position? The example that we just saw had a modal auxiliary in the T-head position. But not all sentences have modals in them. If the sentence does not have a modal auxiliary, then the T-head position will be occupied by a morphosyntactic tense feature. And when we’re looking at English, there are only two tense features, [-past] and [+past].

Let’s see how this works in another simple sentence, very similar to the last one: Alex loves yoga. Remember that the theory claims that when we draw a verb in its tensed form from the mental lexicon, we also bring along the tense feature as well. Loves is in the present tense, so it has the [-past] feature.

The structure of this sentence is the same as the previous one we looked at. The only difference is that, instead of a modal auxiliary in the T position, we have that morphosyntactic tense feature. We put this feature in brackets to indicate that it’s present in our mental grammar but it doesn’t actually get pronounced when we say the sentence out loud. You could think of it as present in the underlying form, but not in the surface form. The job of this feature in the T-head position is to make sure that its complement has the correct form. Since this feature is [-past], it wants to make sure that the verb in its VP complement is in the [-past] (that is, the present-tense) form. If there were some non-tensed form of the verb there, like Alex loving yoga or Alex love yoga, the sentence would be ungrammatical.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

The second option, the one headed by a TP node.

The reason: All sentences are Tense Phrases, or TP's.

- Answer

-

The first one, with the Tense node as a sister node to the VP node.

The reason: Tense nodes are always sister nodes to VPs.

- Answer

-

The second one, with should as an auxiliary.

The reason: Should is an auxiliary, not a tense.

English Verb Forms, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Every English verb has five different forms, but only two of the forms have a tense feature. The tensed forms are indicated with a morphosyntactic feature, either [+past] or [-past]. The form that a verb in the V-head position takes depends on what tense feature is in the T-head position, among other things.

| bare | (non-tensed) | eat | walk | sing | take |

| [-past] | (tensed) | eats | walks | sings | takes |

| [+past] | (tensed) | ate | walked | sang | took |

| past participle | (non-tensed) | eaten | walked | sung | taken |

| present participle | (non-tensed) | eating | walking | singing | taking |

But there are some quirks of English that can make things confusing:

Is it bare or [-past]?

For just about every verb, the [-past] form is recognizable in the 3rd-person-singular form (she eats/walks/sings/takes). The 1st & 2nd-person forms (I eat/walk/sing/take and You eat/walk/sing/take) look just like the bare form (eat/walk/sing/take).

If you’re looking at a verb and can’t tell if it’s in the bare form or the [-past] form, give it a 3rd-person subject and then look for the –s morpheme:

I want to visit Saskatoon. (bare or [-past]? Can’t tell: they’re ambiguous)

She wants to visit Saskatoon. (wants is [-past], visit is bare)

Is it [+past] or past participle?

For many English verbs, the [+past] form (She bought a donut) and the past participle form (She has bought a donut) are the same.

If you’re looking at a verb and can’t tell if it’s in the [+past] form or the past participle form, try replacing it with the verb eat:

She bought a donut after she had walked the dog. ( [+past] or past participle? Can’t tell: they’re ambiguous)

She ate a donut after she had eaten the dog. (Silly, but grammatical)

The form ate is [+past], while eaten is past participle, so we can conclude that, in that sentence, bought is [+past] while walked is the past participle)

What about auxiliaries?

The modal auxiliaries never change their form: they occupy the T-head position in their own right.

The non-modal auxiliaries, like main verbs, change their form depending on what tense feature is in the T-head position, among other things.

| bare | (non-tensed) | be | have | do |

| [-past] | (tensed) | am/are/is | has | does |

| [+past] | (tensed) | was/were | had | did |

| past participle | (non-tensed) | been | had | done |

| present participle | (non-tensed) | being | having | doing |

Subcategories, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

Let’s consider a simple sentence, Jamie might bake cupcakes.This is a perfectly grammatical English sentence, and we can account for it all using x-bar structure. If we change the verb bake to the verb eat, our sentence is still grammatical, Jamie might eat cupcakes. And that makes sense of what we know about how categories work — we group verbs together into the verb category because they behave the same way.

But what about these sentences?

Jamie might arrive cupcakes.

Jamie might hope cupcakes.

Are these grammatical? My mental grammar doesn’t generate these, and I bet yours doesn’t either. And their ungrammaticality isn’t just a matter of them not making semantic sense, either. Since the verb arrive often has something to do with a location, we could try changing cupcakes to Toronto, but the sentence is still ungrammatical: the grammar of English does not generate the sentence, Jamie might arrive Toronto. But why aren’t these sentences grammatical? There’s no doubt that arrive and hope are verbs, and they seem to fit into the same x-bar structure that was grammatical for lots of other sentences. Why doesn’t our mental grammar generate the sentence Jamie might hope cupcakes?

It’s something to do with the verbs themselves. Some heads are picky about the kinds of complements they’re willing to take. And this is especially true for verbs. Within the large category of verbs, we can group verbs further into subcategories according to the kinds of complements they take. For each head, the mental lexicon stores not just syntactic category information, but also subcategory information. The subcategory information tells us what kinds of complements each head will accept. So let’s look at a few verb subcategories.

Transitive Verbs have one complement, a noun phrase, so they have this basic structure. The verb baked is transitive when it has an NP or DP complement like cupcakes. Here are some other transitive structures: drank coffee, likes Linguistics, needs money, speaks Mandarin.

When there is a noun phrase in the complement of a verb, we call it the direct object. And the direct object NP or DP doesn’t have to be a single word. It could be a fairly complex phrase itself. As long as it’s a noun phrase and it’s the complement of a verb head, we call it the direct object, and the verb is a transitive verb.

Intransitive verbs have no complement at all. These are verbs that describe an action or state that involves just a single participant, like sneezed or arrived or dances or slept.

There’s a small set of verbs that are called ditransitives. They’re a little special because they have two complements, but for them to count as ditransitives, they have a special kind of behaviour, called the dative alternation. The best example of a ditransitive verb is the verb give. Take a look at this structure and notice that the V-head gave has two sisters — two complements — the NP cupcakes and the PP to Sarah. But this verb give has another possible grammatical structure that means exactly the same thing. In this alternate structure, the verb has two NP complements. The NP Sarah, which was the complement to the preposition in the other structure, is now the first complement, and cupcakes has become the second complement.

The fact that our mental grammar generates both these structures for this verb and its complements is called an alternation. There are other alternations in our mental lexicon, but this particular one is called the dative alternation, which comes from the Latin word for give. Most of the verbs that allow the dative alternation are verbs that have a meaning that’s related to giving. Send is another example:

She sent a letter to her grandmother. // She sent her grandmother a letter.

Or to hand someone something:

She handed a coffee to her friend. // She handed her friend a coffee.

The last subcategory of verbs to talk about is another small one, but it’s an interesting subcategory. Some verbs take complements that are entire sentences. Each of these verbs, hope, doubt, wonder, ask, has a complement that could stand alone as a sentence:

Ann hopes that the Leafs will win.

Bev doubts that the Leafs can win.

Carla wondered if she should cancel her season’s tickets.

Divya asked whether Eva liked hockey.

Each of these sentences, or clauses, is embedded inside the larger sentence. And each one is introduced by a word from the category of complementizers. The words that, if, and whether are called complementizers because they introduce complement clauses. Let’s look at the structure of one of these sentences.

First, the embedded clause, which could stand as a sentence in its own right — it has a tense feature in the T-head position. The complement to the T-head is, as always, a VP. In this clause, the verb is intransitive so it has no complements, and the entire phrase is made up of the word win. This clause has a subject, a DP in the SpecTP position, the Leafs.

So this whole TP could be a sentence in its own right, but we know that in this case, it’s embedded inside a larger sentence — it’s the complement to the verb hopes. And often when a clause is in complement position, it gets introduced by a complementizer, which is a head of its own that we label as C. Notice that because the complementizer that is a C-head, there is also a C-bar and CP level as well.

Now from here on it’s quite simple. This whole CP is simply the complement of the verb hopes, so it’s sister to the V-head and they’re both daughters of V-bar. And then this matrix clause has its own T-head, T-bar and TP levels, and the subject NP in SpecTP is Ann.

OK, let’s recap. We’ve seen now that in addition to category information, the mental lexicon includes subcategory information for some heads. Verbs belonging to different subcategories are choosy about the form their complement takes. This means that it would be possible for a given sentence to be ungrammatical even if it has an x-bar structure if the complement is the wrong kind for that subcategory of head. And we’ve looked at four different verb subcategories:

- transitive verbs have one NP or DP as their complement

- intransitive verbs have no complements

- ditransitive verbs have two complements that can alternate position in the dative alternation

- and there is a set of verbs that take clauses as their complements

What is the subcategory of the bolded verb in this sentence?

The soccer players kicked the ball.

- Verb with a complement clause

- Ditransitive

- Intransitive

- Transitive

- Answer

-

"Transitive"

The reason: The verb kicked requires a NP clause as a complement.

What is the subcategory of the bolded verb in this sentence?

Many birds fly over Ontario each fall.

- Verb with a complement clause

- Ditransitive

- Intransitive

- Transitive

- Answer

-

"Intransitive"

The reason: The verb fly cannot have an NP as a complement.

What is the subcategory of the bolded verb in this sentence?

This game teaches children the alphabet.

- Verb with a complement clause

- Ditransitive

- Intransitive

- Transitive

- Answer

-

"Ditransitive"

The reason: The verb teaches requires both an NP complement and a PP complement.

Grammatical Roles, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

We use grammatical role labels to identify the syntactic position of Noun Phrases or Determiner Phrases within each clause. It’s vital to remember that grammatical role labels are defined strictly according to syntactic positions, not according to the meaning of a noun phrase or its semantic relationship to the verb. We’ll come back to this idea in the next chapter.

The subject is the NP or DP that appears in the Specifier of TP. The underlined phrases in the following sentences are all subjects of their respective clauses.

Zora kicked the soccer ball.

Yasmin guessed that Xavier would probably be late.

That tall woman nearly knocked me over.

The view from the top floor is quite impressive.

Understanding Calculus takes a lot of work.

The town where I was born recently elected a new mayor.

The direct object is an NP or DP that is the complement to a Verb head. Each of the following underlined phrases is a direct object.

Zora kicked the soccer ball.

Xavier’s lateness annoyed Yasmin.

William convinced Veronica that class was cancelled.

Ursula asked the fellow who works at Tim Horton’s what time the store closed.

Stefanie bought a gift certificate for $100 for her mother.

If we refer to an NP or DP simply as the object, by default we mean the direct object, not the indirect object (see below).

If a Verb head takes a complement that is some category other than an NP or DP, then that complement phrase does not count as a direct object. The phrases following the verbs in these sentences are NOT direct objects, even though they are complements to V-head, because they are not NPs/DPs.

Yasmin guessed Xavier would be late.

Rana seemed unhappy.

The parcel was on the porch.

We can identify two additional grammatical roles for NPs/DPs, according to the syntactic positions they occupy. An indirect object only appears with a ditransitive verb. It is the NP or DP that alternates between being the complement of a P-head and the complement of a V-head, for a verb that allows the dative alternation. The underlined phrases below are all indirect objects:

Stefanie bought a gift certificate for her mother.

Stefanie bought her mother a gift certificate.

Quinn texted directions to the party to her friends.

Quinn texted her friends directions to the party.

Preeti sent a bouquet of flowers to her aunt.

Preeti sent her aunt a bouquet of flowers.

If a verb does not allow the dative alternation, then it does not have an indirect object.

If an NP or DP appears as the complement to a preposition, but does not an alternate position to become the complement of a verb in the dative alternation, then it is not an indirect object, but an oblique. Oblique is the catch-all label for all other positions that NPs or DPs can occupy in a sentence. The underlined phrases below are all obliques:

Oscar bought a bicycle from that store on Locke Street.

Norma left her business card on the table.

Massimo watched a documentary about antibiotics.

These four labels: subject, direct object, indirect object, and oblique, describe Noun Phrases or Determiner Phrases only in terms of what position they occupy in a clause. Look at the following two sentences:

A famous food critic reviewed this restaurant.

This restaurant was reviewed by a famous food critic.

Even though the person who does the reviewing is the same person (the famous food critic) in both sentences, the DP a famous food critic is not the subject of both sentences, only of the first. The subject of the second sentence is the DP this restaurant. Grammatical role labels describe the syntactic position of noun phrases.

Adjuncts, in Anderson's Essentials of Linguistics

Video Script

We’ve been working at representing how phrases and sentences are organized in the mental grammar, and to do that we’ve been using x-bar theory, which claims that every phrase in every sentence in every language of the world is organized into an x-bar structure. An x-bar structure has a head, a bar-level and a phrase level. It might, optionally, have a complement phrase as the sister to the head and daughter to the bar-level. It might, optionally, have a specifier as sister to the bar level and daughter to the phrase level.

But as you’ve been drawing trees and thinking about how sentences are organized in your mental grammar, you might have encountered some kinds of sentences that don’t seem to fit into an x-bar structure. The X-bar structures that we’ve looked at so far have left out one element. The additional level of structure that we need is called an adjunct, and here’s what it looks like. What structural relationships do you notice? The adjunct is sister to the bar-level, but here’s something we haven’t seen before: it’s also daughter to a bar-level. This is an instance of recursion. A recursive structure is a structure that contains another structure inside it that has the same type as itself. Some linguists argue that recursion is a fundamental property of all human languages and that it’s one of the things that makes human languages different from all other species’ communication systems. Try to think of some other examples of recursive structures that we’ve already seen.

So if adjunction is recursive, you’ve probably already figured out that it can happen over and over again within a single phrase. Every time we add an adjunct as sister to the bar level, we add another bar-level as its mother, to which we could add another adjunct as its sister, which adds another bar level as its mother, and so on. So an x-bar phrase can have 0 or 1 complements, and it can have either 0 or 1 specifies, but because adjuncts are recursive, it could theoretically have an infinite number of adjuncts.

We’ve got a pretty clear idea of what complements do: they complete the meaning of a head. And the specifier position is a special position for subjects. So why do we need adjuncts? Well, like complements and specifiers, adjuncts are optional: a phrase might have one or more, or it might have no adjuncts. Adjuncts often add extra information that’s not totally necessary for the meaning of the sentence, the kind of information that’s often contained in APs or PPs, like where an event happened or how it happened. Because adjuncts are optional, they can often be moved or even removed altogether without changing the grammaticality of the sentence. And many adjuncts can appear on either side of their x-bar sister, whereas in English, complements pretty much always come after their sisters and specifiers come before. Let’s look at some examples of adjunct phrases.

In this sentence, Sam bought shoes yesterday, the phrase yesterday is giving us extra information about when the buying happened, so it’s adjoined within the verb phrase headed by bought.

In this next one, Sam bought new shoes yesterday, the adjective new is giving us extra information about the noun, shoes, so it’s adjoined within the noun phrase that has shoes as its head. Notice that this AP is still in adjunct position: it’s sister to N’ and daughter to N’, but it happens to come before its sister instead of after.

And look at all the adjuncts in this one: Ted snored loudly for several hours at night. We know that the verb snore is an intransitive verb: it doesn’t take anything as its complement, so the head has no sister. But then there are three separate adjunct phrases, each of which gives us extra information about the snoring: the AP loudly is sister to V’ and daughter to another V’ node.The PP for several hours is sister to V’ and daughter of another V’ node. And the PP at night is sister to V’ and daughter to another V’ node. I’ve drawn these phrases with triangles; that’s just a shorthand that indicates that we’re not depicting the full inner structure of these phrases.

One piece of evidence that these phrases are adjuncts and not specifiers is that we can rearrange them in the sentence without changing the meaning or the grammaticality of the sentence.

Ted snored loudly for several hours at night.

Ted loudly snored at night for several hours

Ted snored for several hours at night, loudly.

If any of these phrases were complements, we wouldn’t be able to move them around, because a complement is always sister to the head, so it has to be right beside the head. But because adjunction is recursive, an adjunct always introduces another bar-level that can accommodate another adjunct.

So from now on, when you’re drawing trees, you don’t just have to decide whether each phrase goes in a complement or specifier position, but you also have to consider whether it might be an adjunct.

Check Yourself

- Answer

-

"Complement"

The reason: The verb ran can have an NP as a complement and fills in needed information.

- Answer

-

"Adjunct"

The reason: The phrase this morning is not needed information to complete ran; it's additional

- Answer

-

"Adjunct"

The reason: The phrase this morning is not needed information to complete ran; it's additional

Phrase Structure Rules, X-Bar Theory, and Constituency, from Sarah Harmon

Video Script

Anderson does an excellent job of walking you through a phrase structure tree. I'm just going to add a little bit more.

If you want a basic set of phrase structure rules for English—and it should be noted, this is most all dialects of English, not all but most all—this is one set that you can use.

S → NP VP

S → CP VP

CP → (Comp) S

NP → (Det) (AdjP) N’ (CP) (PP) (CoordP)

N’ → (AdjP) N’ (PP)

N’ → N

NP → NP’s N’

NP → Pro

NP → [proper name]

VP → V’ (CP) (NP) (AdjP) (PP) (CoordP) (AdvP)

V’ → V

V’ → Aux V’

AdjP → Adj (N’) (CoordP)

AdvP → Adv (PP) (CoordP)

PP → P NP (CoordP)

CoordP → Coord XP

Catherine has a slightly modified version of this but either set will work just fine. What's important to note is that for every type of phrase, there is a head and a complement. The head is the crucial piece of that phrase, and then the complement is the supporting cast, as it were. For example, the head of a noun phrase is always going to be a noun.

All of these little codes, as it were, are a nice shorthand for trying to decipher what role that piece has. Instead of thinking of individual morphemes and lexicons and puzzle pieces, think bigger. Think big steel beams that are being used to set up the structure of a building; that's basically what phrase structure rules are.

As Anderson talks about, we're going to be using X-Bar Theory. It has been around for quite some time, about 40 years. It is still the prevailing method of doing basic syntactic analysis; we'll talk more about that soon enough. She does an excellent job of explaining it, it is really a great tool, not just to analyze the syntax. Morphology as well; you can use this type of structure this branching tree structure to analyze how more things are put together in a language, to create lexicon. Then you can use it to create the structure of a sentence or phrase in a given language. It has used been used for pretty much every language that is in existence; there's only a very few that it doesn't work for.

Catherine talks quite a bit about constituency, so I’m going to leave that there, but I do want to bring up recursion. It is one of the great ways to analyze a specific phrase structure of a specific language: to look at what has allowed with respect to recursion. Recursion actually refers to that hallmark of language called duality, that we have a limited number of resources, but we can make an infinite number of statements or sentences in a given language. For example, if we scroll back to our phrase structure rules, this more or less covers every single possible sentence and phrase in English. You pretty much can blueprint English based off of these rules. Yet, these few rules explain pretty much every possible statement that you can make in English; that's recursion. It also shows up in the fact that you can have nesting of different types of phrases. For example, a noun phrase can have a propositional phrase as a complement, so ‘the cat in the house’. ‘In the house’ is modifying or describing ‘cat’. Notice that a prepositional phrase can have a noun phrase as one of its components; in fact, it has to have a noun phrase. ‘In the House’, there's your prepositional phrase, and then that noun phrase itself can get further modified by another propositional phrase: ‘the cat in the house down the hill on the river next to the forest’ and on and on and on. You can keep building quite a number of these recursive statements.

That's possible. Is it probable? Well, no, it's not. There is a tendency to kind of keep a limit as to how many recursive elements you put in. If you think about it, that makes sense; if I start to describe where I live, ‘I live in a house on a street in the town by the river next to the forest through the gap down the gulch…’. After a minute, you stop being able to keep track of where my house is. There seems to be a limit, three to four phrases are the rough limit. That being said, could we build a structure as tall and as far as we can see? Sure. Do we do that? No, we tend to keep a limit to our height of building; we also tend to put a limit on how many recursive elements we tend to include.