9.4: Child Language Acquisition Linguistics

- Page ID

- 114816

Child Language Acquisition Linguistics, from Sarah Harmon

Video Script

Let's break down those stages of child language acquisition a little bit more, and specifically the patterns that we observed of how children learn their first language or languages. I keep phrasing it this way, because not all children grow up in a monolingual society; many children grow up in a at least a bilingual society, if not a multilingual society. What we can say is that, regardless of how many linguistic inputs they are receiving with respect to individual languages, we see the following patterns.

Phonology

With phonology, there is a progression on the sounds that children tend to learn first. Whatever the language or languages that they're learning, the progression tends to be the same. When we're talking about manner of articulation, nasal and glides are first, because there's the least amount of control needed to produce those sounds. You don't have to move your articulators so much. Then come stops, then liquids, then fricatives, then affricates.

Let's think about the very young children that you are around. If you think about how they talk at their youngest stages, the first words that they come up with all have lots of nasals, some glides and some stops. If it's a language that's heavy on the fricatives and affricates, those sounds aren’t produced very early on. Think of the French-German example that we saw in very first section of this chapter; the child having the worst time with not one, but two different consonant clusters. One of the consonant clusters was an actual affricate, the [pf]; the [kn] is just a consonant cluster. In either case, the child couldn't do it, and simplified everything; he used a basic nasal and a basic stop in their places.

The same is true with place of articulation: labials and velars are the early sounds, and then the sounds in the middle come later, with more precision of the articulators. Palatals are universally the last sounds that the child acquires and articulate well.

I really want to focus on this articulation aspect, that it's the performance that comes late, not the competence. They understand and recognize those sounds, even as early as six months of age. However, producing the sounds that is a different story. The distinction of voiced versus voiceless is an articulation that comes pretty early. Children produce more voiced sounds to start off, and then voiceless sounds come a little bit later.

Think about early words that most children acquire, frequently having to do with mom or dad, because those are the folks that they're mostly around. Those sounds tend to have a lot of nasals and a lot of labials. There early errors in pronunciation, but they're always rule governed. Remember what we said about language change: it's always rule governed. Acquisition is no different.

There is a very strong tendency for children to simplify consonant clusters; we saw this with the French-German example, and you know plenty of other examples. The voicing of final consonants, not just with English, but in general, is also a strong tendency, and it makes sense. When we are trying to articulate the end of a lexicon, getting that pronunciation at the end is very crucial. The more consonants you have in the coda of the last syllable, the harder it gets to articulate them, and young children tend to chop off the end of the lexicon, and especially the last coda. There's always this consistent voicing of initial consonants and consonant harmony; again, creating patterns and using them in the production of the language.

We see these patterns and tendencies in language after language, in child after child; we see this both in monolingual and multilingual situations. For example, if you have a child who grows up in a bilingual house with bilingual parents, they're going to go through this process with both languages. Remember, competence before performance; we know these children, even at six months, are starting to differentiate the sounds of the language or languages around them. By one year of age, they understand the sounds of whatever languages are around them. They may not be able to produce the sounds correctly, but they understand and recognize them.

Morphology

With respect to morphology, there are some pretty basic changes that we observe. Overgeneralization—we've heard that one before. An example is the foot, foots or feet, feets, along those lines. We see this in pluralization and in all aspects of language; anytime there's any kind of irregularity—and every language has irregularity—then there's going to be some overgeneralization always.

We're still trying to understand why it is the case that children pick up and produce standard pluralization very quickly, whatever language. This is also true of other basic inflection and morpho-syntactic structures. Think back to syntax with respect to subject-verb agreement and the Linear Agreement Rule; that's something that's learned very quickly. The same is true with noun-adjective agreement; if the noun has a certain gender and/or number classification, and it gets inflected as well on the adjective, then that is learned very quickly. The basic derivational rules are also learned very early on; that's why children are able to overgeneralize, because they have learned the basic derivational rules.

One of my favorite activities to do with young children, even as young as two or three, once they start putting those two- to five-word sentences together, I have them tell me stories. I love hearing the combinations that they put together with respect to lexicon; they come up with the best ones.

Syntax, Semantics and Pragmatics

When we talk about syntax, semantics and pragmatics, let's be clear: syntax is kind of on one end of the learning spectrum, and semantics and pragmatics is the other. Basic syntax is learned pretty early on; as the child acquires more is able to produce more. But semantic elements are harder to measure. It's difficult to measure, outside of asking the child, “What does this?”, “What do you call this thing?” We can do that kind of lexical analysis as to how many words the child can produce, as well as how many they can understand. Studies where you have a child in a lab, and the researcher holds this thing (🍼) up using the incorrect name for the item; the babies and toddlers know it's not the correct name. They just may not be able to say ‘bottle’ or [baba]. For example, if I say, “it's zork,” they're going to say, “No, that's not a zork. It’s a bottle.”

Pragmatic elements are even more difficult to measure. That's true just because of the development of a child's brain; these concepts of politeness, of reading between the lines, of implicature and presupposition, the Maxims of the Cooperation Principles, these are things that a child does not acquire until well into childhood. Most commonly, children don’t understand these concepts well until between the years of seven or six, perhaps not until 9-12, and not until teenage years in some cases. Much of this is culturally simulated, as you would expect, and that's why young children don't understand this. The phrase, “Honesty out of the mouths of babes,” or something along those lines, is seemingly ubiquitous because children don't know when not to say something or how to rephrase it.

That all being said, syntax-semantic relationships, like auxiliaries (like be, have, will or would) and modals (like could, should, must, or do) are learned not too early, but not too late; usually somewhere in that three- to four-year range. The more stimulus the babies and toddlers are around, the quicker they pick things up, but also the more complex they become earlier on.

That being said, that doesn't mean all of their input has to be super complex for a number of years. It honestly seems to be cyclical; there have been many times, where the prevailing theory is that you have to surround your children with high level language from the earliest of times. That's not necessarily going to ensure that your child understands, let alone produces, those terms. It is important to understand, though, that just because they hear Cookie Monster all the time, that doesn't mean they're going to talk like Cookie Monster.

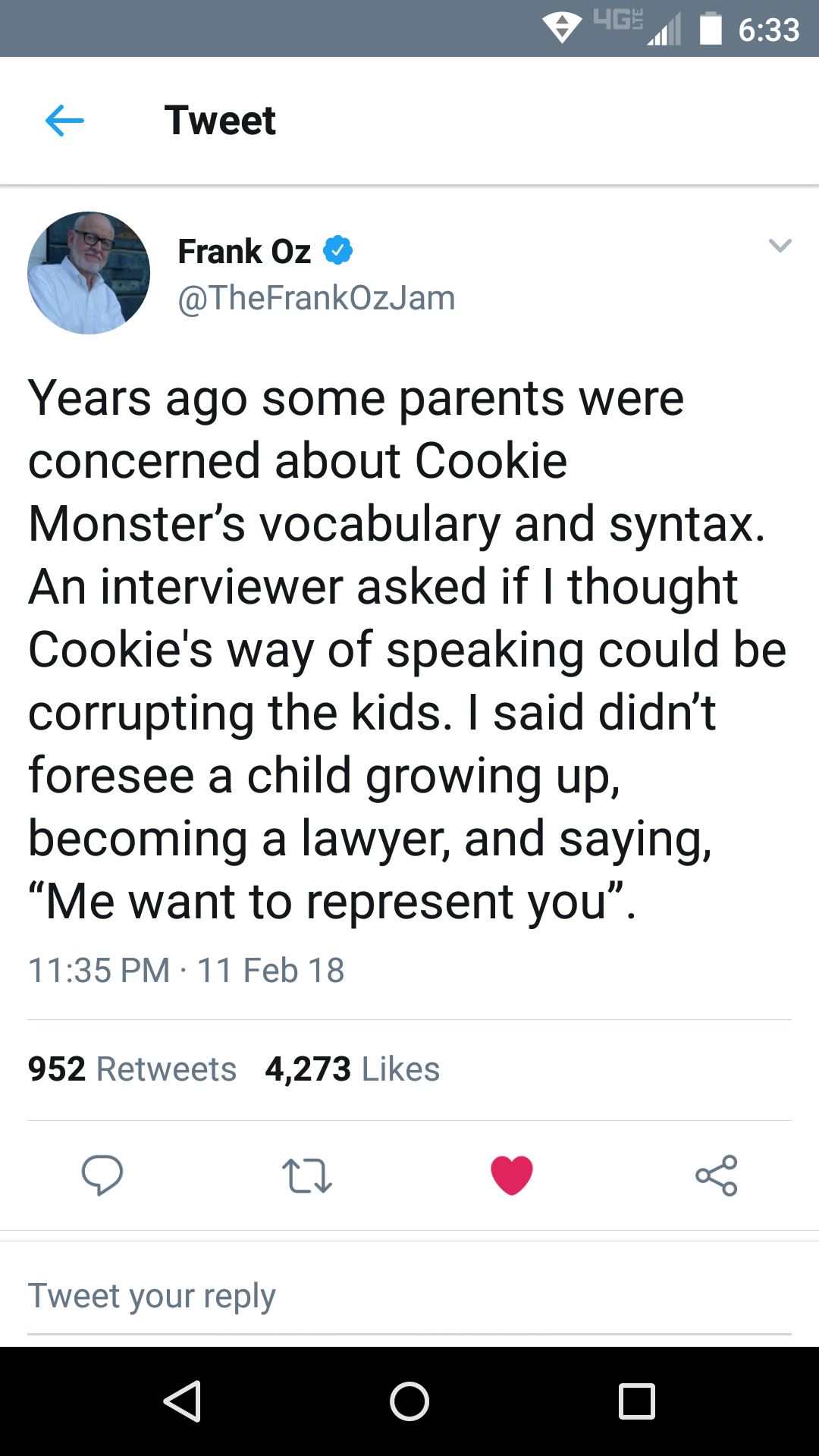

This is something that Frank Oz, who created the character of Cookie Monster, as well as voiced him for many decades. I love this; I guess this has happened throughout his career, that the parents were concerned about Cookie Monster's vocabulary and syntax. Somebody asked him if he thought that Cookie’s way of speaking could corrupt the children that were watching Sesame Street. He said that he didn't foresee a child growing up to become a lawyer and saying, “Me want to represent you.”

I think Frank is on to something.