11.1: The Interplay of Sex and Gender

- Page ID

- 55246

A quick review of some biological basics will lay a good foundation for a more detailed discussion of the interplay between sex and gender in communication studies.

Sex

As you may recall from a biology or health class, a fetus’s sex is determined at conception by the chromosomal composition of the fertilized egg. The most common chromosome patterns are XX (female) and XY (male). After about seven weeks of gestation, a fetus begins to receive the hormones that cause sex organs to develop. Fetuses with a Y chromosome receive androgens that produce male sex organs (prostate) and external genitalia (penis and testes). Fetuses without androgens develop female sex organs (ovaries and uterus) and external genitalia (clitoris and vagina). In cases where hormones are not produced along the two most common patterns, a fetus may develop biological characteristics of each sex. These people are considered intersexuals.

Pin It!

Case In Point- Intersexuality

According to the Intersex Society of North America,“Intersex” is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male. For example, a person might be born appearing to be female on the outside but having mostly male-typical anatomy on the inside. Or a person may be born with genitals that seem to be in-between the usual male and female types—for example, a girl may be born with a noticeably large clitoris, or lacking a vaginal opening, or a boy may be born with a notably small penis, or with a scrotum that is divided so that it has formed more like labia. Or a person may be born with mosaic genetics, so that some of her cells have XX chromosomes and some of them have XY.

Though we speak of intersex as an inborn condition, intersex anatomy doesn’t always show up at birth. Sometimes a person isn’t found to have intersex anatomy until she or he reaches the age of puberty, or finds himself an infertile adult, or dies of old age and is autopsied. Some people live and die with intersex anatomy without anyone (including themselves) ever knowing. Which variations of sexual anatomy count as intersex? In practice, different people have different answers to that question. That’s not surprising, because intersex isn’t a discreet or natural category.

What does this mean? Intersex is a socially constructed category that reflects real biological variation. To better explain this, we can liken the sex spectrum to the color spectrum. There’s no question that in nature there are different wavelengths that translate into colors most of us see as red, blue, orange, yellow. But the decision to distinguish, say, between orange and red-orange is made only when we need it—like when we’re asking for a particular paint color. Sometimes social necessity leads us to make color distinctions that otherwise would seem incorrect or irrational, as, for instance, when we call certain people “black” or “white” when they’re not especially black or white as we would otherwise use the terms.

In the same way, nature presents us with sex anatomy spectrums. Breasts, penises, clitorises, scrotums, labia, gonads—all of these vary in size and shape and morphology. So-called “sex” chromosomes can vary quite a bit, too. But in human cultures, sex categories get simplified into male, female, and sometimes intersex, in order to simplify social interactions, express what we know and feel, and maintain order.

So nature doesn’t decide where the category of “male” ends and the category of “intersex” begins, or where the category of “intersex” ends and the category of “female” begins. Humans decide. Humans (today, typically doctors) decide how small a penis has to be, or how unusual a combination of parts has to be, before it counts as intersex. Humans decide whether a person with XXY chromosomes or XY chromosomes and androgen insensitivity will count as intersex.

In our work, we find that doctors’ opinions about what should count as “intersex” vary substantially. Some think you have to have “ambiguous genitalia” to count as intersex, even if your inside is mostly of one sex and your outside is mostly of another. Some think your brain has to be exposed to an unusual mix of hormones prenatally to count as intersex—so that even if you’re born with atypical genitalia, you’re not intersex unless your brain experienced atypical development. And some think you have to have both ovarian and testicular tissue to count as intersex.

Rather than trying to play a semantic game that never ends, there is a pragmatic approach to the question of who counts as intersex. We work to build a world free of shame, secrecy, and unwanted genital surgeries for anyone born with what someone believes to be non-standard sexual anatomy. By the way, because some forms of intersex signal underlying metabolic concerns, a person who thinks she or he might be intersex should seek a diagnosis and find out if she or he needs professional healthcare.

As you know, hormones continue to affect us after birth—throughout our entire lives, in fact. For example, hormones control when and how much women menstruate, how much body and facial hair we grow, and the amount of muscle mass we are capable of developing. Although the influence of hormones on our development and existence is very real, there is no strong, conclusive evidence that they alone determine gender behavior. The degree to which personality is influenced by the interplay of biological, cultural, and social factors is one of the primary focal points of gender studies.

Gender

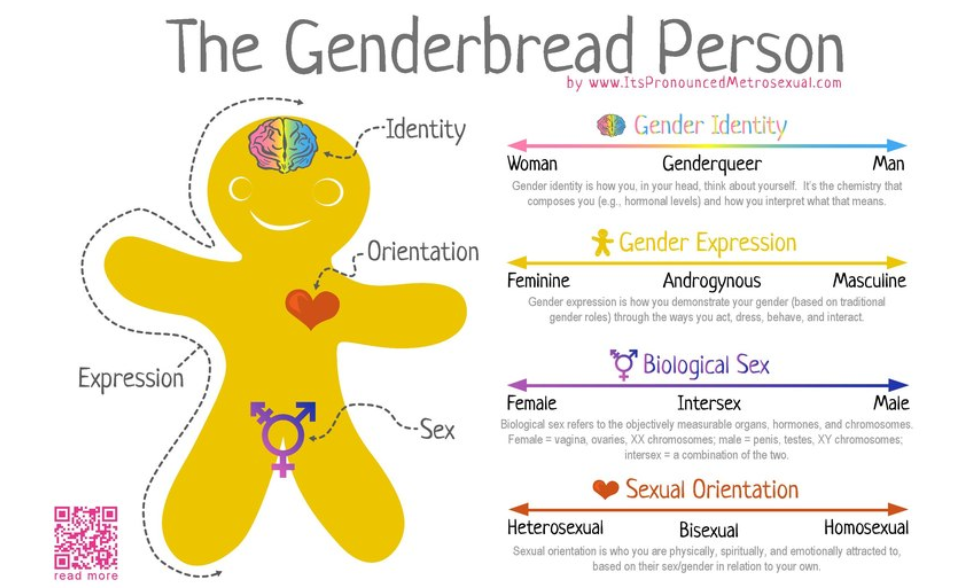

Compared with sex, which biology establishes, gender doesn’t have such a clear source of influence. Gender is socially constructed because it refers to what it means to be a woman (feminine) or a man (masculine). Traditionally, masculine and feminine characteristics have been taught as complete opposites when in reality there are many similarities. Gender has previously been thought of as a spectrum, as a line; this implies the drastic separation of genders. A better way to think about gender is a circle, where all genders can exist in relation to each other.

One expression of gender is known as androgyny, the term we use to identify gendered behavior that lies between feminine and masculine—-the look of indeterminate gender. Gender can be seen as existing in a fluid circle because feminine males and masculine females are not only possible but common, and the varying degrees of masculinity and femininity we see (and embody ourselves) are often separate from sexual orientation or preference. The circle chart illustrates how all genders exist on a sort of plane. They are not arranged in a straight line, with female on one end, and male on the other. There are no set borders to any one gender, and there is open space for people to define themselves however they uniquely identify.

Use your phone to visit the QR code in the image below or visit this website (link: https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2011/11/breaking-through-the-binary-gender-explained-using-continuums/) for more information.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Genderbread Person1

The Social Construction of Gender

In this section, we will discuss how gender is dynamic, social, symbolic, and cultural. Gender is dynamic, not just because it exists on a plane, but because its meanings change over time within different cultural contexts. For example, in 1907, women in the United States did not have the legal right to vote, let alone the option of holding public office. Although a few worked outside the home, women were expected to marry and raise children. A woman who worked, did not marry, and had no children was considered unusual, if not an outright failure. Now, of course, women have the right to vote and are considered an important voting block. There are many women who are members of local and state governing bodies as well as the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, even though they aren’t representative in government of their 51 percent of the population. Similarly, men were also prescribed to fill a role by society one hundred years ago: marriage and wage earner. Men were discouraged from being too involved in the raising of children, let alone being stay-at-home dads. Increasingly, men are accepted as suitable child-care providers and have the option to stay home and raise children.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Genderlegs2

As a social construct, gender is learned, symbolic, and dynamic. We say that gender is learned because we are not born knowing how to act masculine or feminine, as a man or a woman, or even as a boy or a girl. Just as we rely on others to teach us basic social conventions, we also rely on others to teach us how to look and act like our gender. Whether that process of learning begins with our being dressed in clothes traditionally associated with our sex (blue for males and pink for females), or being discouraged from playing with a toy not associated with our sex (dolls for boys, guns for girls), the learning of our genders begins at some point. Once it’s begun (usually within our families), society reinforces the gender behaviors we learn. Despite some parents’ best efforts to not impose gender expectations on their children, we all know what is expected of our individual gender.

Gender is symbolic. It is learned and expressed through language and behavior. Language is central to the way we learn about gender and enact it through communicative acts because language is social and symbolic. Remember what we learned in chapter two, that language is symbolic because the word “man” isn’t a real man. It is a symbol that identifies the physical entity that is a human male. So, when a mother says to her children, “Be a good girl and help me bake cookies,” or “Boys don’t cry” children are learning through symbols (language) how to “be” their gender. The toys we are given, the colors our rooms are painted, and the after-school activities in which we are encouraged to participate are all symbolic ways we internalize, and ultimately act out, our gender identity.

Pin It!

Case In Point – Representation

The franchise, Dick’s Sporting Goods, received much backlash after 12 year old McKenna Peterson brought attention to the lack of females in their Fall 2014 Basketball catalog. The issue was brought to the corporation’s attention when Mckenna’s father posted a picture of her letter to the company to his Twitter account. McKenna writes, “There are NO girls in the catalog! Oh, wait, sorry. There IS a girl in the catalog on page 6. SITTING in the STANDS. Women are…mentioned once…for some shoes. And there are cheerleaders on some coupons. It’s hard enough for girls to break through in this sport as it is, without you guys excluding us from your catalog.” Dick’s CEO, Ed Stack, has since apologized to McKenna and admitted it was a mistake to not have female athletes, and promises that they will be featured in next year’s issue. However, Dick’s might communicate inclusivity to female athletes if they redid their recently released catalog to include female athletes now, because we know that women play ball the same as men and don’t just sit on the sidelines.

Finally, gender communication is cultural. Meanings for masculinity and femininity, and ways of communicating those identities, are largely determined by culture. A culture is made up of belief systems, values, and behaviors that support a particular ideology or social system. How we communicate our gender is influenced by the values and beliefs of our particular culture. What is considered appropriate gender behavior in one culture may be looked down upon in another. In America, women often wear shorts and tank tops to keep cool in the summer. Think back to summer vacations to popular American tourist destinations where casual dress is the norm. If you were to travel to Rome, Italy to visit the Vatican, this style of dress is not allowed. There, women are expected to dress in more formal attire, to reveal less skin, and to cover their hair as a display of respect. Not only does culture influence how we communicate gender identities, it also influences the interpretation, understanding, or judgment of the gender displays of others (Kyratzis & Guo; Ramsey). Additionally, popular media, such as commercials and catalogs can dictate how culture communicates gender roles.

Theories of Gender Development

We said earlier that gender is socially learned, but we did not say specifically just what that process looks like. Socialization occurs through our interactions, but that is not as simple as it may seem. Below we describe five different theories of gender development.

Psychodynamic. Psychodynamic theory has its roots in the work of Viennese Psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud. This theory sees the role of the family, the mother in particular, as crucial in shaping one’s gender identity. Boys and girls shape their identity in relation to that of their mother. Because girls are like their mothers biologically they see themselves as connected to her. Because boy are biologically different or separate from their mother, they construct their gender identity in contrast to their mother. When asked about his gender identity development, one of our male students explained, “I remember learning that I was a boy while showering with my mom one day. I noticed that I had something that she didn’t.” This student’s experience exemplifies the use of psychodynamic theory in understanding gender development.

Symbolic Interactionism. Symbolic Interactionism (George Herbert Mead) is based specifically on communication. Although not developed specifically for use in understanding gender development, it has particular applicability here. Because gender is learned through communication in cultural contexts, communication is vital for the transformation of such messages. When young girls are told to “sit up straight like a lady” or boys are told “gentlemen open doors for others,” girls and boys learn how to be gendered (as masculine and feminine) through the words (symbols) told to them by others (interaction).

Social Learning. Social Learning theory is based on outward motivational factors that argue that if children receive positive reinforcement, they are motivated to continue a particular behavior. If they receive punishment or other indicators of disapproval, they are more motivated to stop that behavior. In terms of gender development, children receive praise if they engage in culturally appropriate gender displays and punishment if they do not. When aggressiveness in boys is met with acceptance, or a “boys will be boys” attitude, but a girl’s aggressiveness earns them little attention, the two children learn different meanings for aggressiveness as it relates to their gender development. Thus, boys may continue being aggressive while girls may drop it out of their repertoire.

Cognitive Learning. Unlike Social Learning theory that is based on external rewards and punishments, Cognitive Learning theory states that children develop gender at their own levels. The model, formulated by Kohlberg, asserts that children recognize their gender identity around age three but do not see it as relatively fixed until the ages of five to seven. This identity marker provides children with a schema (A set of observed or spoken rules for how social or cultural interactions should happen.) in which to organize much of their behavior and that of others. Thus, they look for role models to emulate maleness or femaleness as they grow older.

Standpoint. Earlier we wrote about the important role of culture in understanding gender. Standpoint theory places culture at the nexus for understanding gender development. Theorists such as Collins and Harding recognize identity markers such as race and class as important to gender in the process of identity construction. Probably obvious to you is the fact that our culture, and many others, are organized hierarchically—some groups of people have more social capital or cultural privilege than others. In the dominant U.S. culture, a well-educated, upper-middle class Caucasian male has certain sociopolitical advantages that a working-class African American female may not. Because of the different opportunities available to people based on their identity markers (or standpoints), humans grow to see themselves in particular ways. An expectation common to upper middle-class families, for example, is that children will grow up and attend college. As a result of hearing, “Where are you going to college”? as opposed to “Are you going to college”? these children may grow up thinking that college attendance is the norm. From their class standing, or standpoint, going to college is presented as the norm. Contrast this to children of the economically elite who may frame their college attendance around the question of “Which Ivy League school should I attend?” Or, the first -generation college student who may never have thought they would be in the privileged position of sitting in a university classroom. In all of these cases, the children begin to frame their identity and role in the society based on the values and opportunities offered by a particular standpoint.

What Do We Study When We Study Gender Communication?

Let’s take a moment to describe in more detail many of the specific areas of gender and communication study discussed in this chapter. You know by now that the field of Communication is divided up into specializations such as interpersonal, organizational, mass media. Within these particular contexts gender is an important variable, thus, much of the gender research can also be integrated into most of these specializations.

There are many kinds of personal relationships central to our lives wherein gender plays an important role. The most obvious one is romantic relationships. Whether it takes place in the context of gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, or heterosexual relationships, the gender of the couple will have an impact on communication in the relationship as well as relational expectations placed on them from the culture at large. After a man and woman marry, for example, a common question for family and friends to ask is, “So, when are you having a baby?” The assumption is when not if. Since gay and lesbian couples must go outside their relationship for the biological maternal or paternal role, they may be less likely to be asked such a question.

Other interpersonal relationships occur in families and friendships where gender is a consistent component. You may have noticed growing up that the boys and girls in your household received different treatment around chores or curfews. You may also notice that the nature of your female and male friendships, while both valuable, manifest themselves differently. These are just a couple of examples that gender communication scholars’ study regarding how gender impacts interpersonal relationships.

Gender and Organizational Communication

While Liberal Feminist organizations such as NOW have made great strides for women in the workplace, gender continues to influence the organizational lives of both men and women. Issues such as equal pay for equal work, maternity and paternity leave, sexual harassment, and on-site family care facilities all have gender at their core. Those who study gender in these contexts are interested in the ways gender influences the policies and roles people play in organizational contexts. See the Case In Point for information on the current wage-gap.

Pin It!

Case In Point - The Wage-Gap Widens

According to the U.S. General Accounting Office (a nonpartisan group), the wage gap between the sexes is widening, not getting better. In 2012 women earned 81 cents to every dollar earned by their male counterparts. In 2013 that fell to 78 cents. The disparity is even greater when kids are involved, citing the GAO’s research, Strasburg explains, “Men with kids earn 2.1 percent more, on average, than men without kids. Women with kids earn 2.5 percent less than women without kids” (14). The cause of the disparity is a complex one—-involving economics, education, science, public relations, and social gender roles. If women, for example, are expected to take on a more passive role in the public sphere, they may feel less inclined to negotiate for a higher salary or ask for a raise.

Gender and Mass Communication

A particular focal point of gender and communication focuses on ways in which males and females are represented in culture by mass media. The majority of this representation in the 21st century occurs through channels of mass media—-television, radio, films, magazines, music videos, video games, and the internet. From the verbal and nonverbal images sold to us as media consumers, we learn the “proper” roles and styles of being male and female in American culture. During World War II, for example, there was a shortage of workers in factories because many of the workers (men) were being sent overseas to fight. Needing to replace them to keep the factories in business, the media launched a campaign to convince women that the best way they could support the war effort was to go out and get a job. Thus, we saw a large influx of women in the workplace. All was fine until the war ended and the men returned home. When they wanted their jobs back, they discovered that they were already filled—-by women! The media once again launched a campaign to convince women that their proper place was now back in the home raising children. Thus, many women left paid employment and returned to a more traditional role (This phenomenon is depicted in the film, Rosie the Riveter).

As media and technology increases in sophistication and presence, they become new sites of gender display and performance. More examples of this can be seen in the increase of women filling leadership roles and men portrayed in nurturing home environments in television and advertising (Krolokke). The comedy series, “Up All Night,” that ran on NBC from September 2011 to December 2012 reflects this idea. The mom, Reagan, goes back to work as a talk show producer after having a baby while husband, Chris stays at home with their newborn. However, there is still a serious lack of strong female roles in the media. Fortunately for women, one Oscar winning actress, Reese Witherspoon has decided to do something about this. In 2012, Witherspoon “grew increasingly frustrated by the answers she got to her question, ‘What are you developing for women?’” (Riley). In her search for a production with a female lead she recalls discovering only “one studio that had a project for a female lead over 30,” and thought, “‘I’ve got to get busy.’ After ‘getting busy’, Witherspoon, along with female Australian producer Bruna Papandrea, started Pacific Standard Production Company that focuses on producing films with a strong female lead. Since the company’s start, Witherspoon and Papandrea have produced two films, “Gone Girl,” based on the novel by Gillian Flynn, and “Wild”, the best-selling memoir by Cheryl Strayed; both released in December 2014. To read more about Witherspoon and her pursuit for women roles read the article by the Columbus Dispatch.

References

- Image by Sam Killermann is in the public domain

- Image by Spaynton is under CC BY-SA 4.0