3.2: The Purpose of Monitoring, Screening and Evaluating Young Children

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 77799

- Gina Peterson and Emily Elam

- College of the Canyons

Because many parents are not familiar with developmental milestones, they might not recognize that their child has a developmental delay or disability. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “In the United States, about 1 in 6 children aged 3 to 17 years have one or more developmental or behavioral disabilities, such as autism, a learning disorder, or attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).” What’s more concerning is that many children are not being identified as having a delay or disability until they are in elementary school . Subsequently, they will not receive the appropriate support and services they need early on to be successful at school. It has been well-documented, in both educational and medical professional literature, that developmental outcomes for young children with delays and disabilities can be greatly improved with early identification and intervention (Squires, Nickel, & Eisert, 1996; Shonkoff & Meisels, 2000). While some parents might be in denial and struggling with the uncertainty of having a child with special needs, some parents might not be aware that there are support services available for young children and they may not know how to advocate for their child. Thus, as early child educators we have an obligation to help families navigate through the process of monitoring, as well as provide information and resources if a screening or evaluation is necessary.

The Process of Monitoring

Who can monitor a child’s development? Parents, grandparents, early caregivers, providers and teachers can monitor the children in their care. As previously stated in Chapter 3, one of the tasks of an intentional teacher is to gather baseline data within the first 60 days of a child starting their program. With each observation, teachers are listening to how a child speaks and if they can communicate effectively; they are watching to see how the child plays and interacts with their peers; and they are recording how the child processes information and problem solves. By monitoring a child closely, not only can we observe how a child grows and develops, we can track changes over time. More importantly, we can identify children who fall outside the parameters of what is considered normal or “typical” development.

When teachers monitor children, they are observing and documenting whether children are mastering “typical” developmental milestones in the physical, cognitive, language, emotional and social domains of development. In particular, teachers are tracking a child’s speech and language development, problem-solving skills, fine and gross motor skills, social skills and behaviors, so that they can be more responsive to each child’s individual needs. Even more so, teachers are trying to figure out what a child can do, and if there are any “red flags” or developmental areas that need further support. As early caregivers and teachers, we are not qualified to formally screen and evaluate children. We can however monitor children’s actions, ask questions that can guide our observations, track developmental milestones, and record our observations. With this vital information we can make more informed decisions on what is in the child’s best interest.

What is this Child Trying to Tell Me?

With 12-24 busy children in a classroom, there are bound to be occasional outbursts and challenging behaviors to contend with. In fact, a portion of a teacher’s day is typically spent guiding challenging behaviors. With all the numerous duties and responsibilities that a teacher performs daily, dealing with challenging behaviors can be taxing. When a child repeats a challenging behavior, we might be bothered, frustrated, or even confused by their actions. We might find ourselves asking questions like:

“Why does she keep pinching her classmate?"

“Why does he put his snack in his hair?”

“Why does he cry when it’s clean up time or when he has to put his shoes on?”

“Why does she fidget so much during group time?”

Without taking the time to observe the potential causes and outcomes associated with the challenging behavior, we may only be putting on band-aids to fix a problem, rather than trying to solve the problem. Without understanding the why , we cannot properly guide the child or support the whole-child’s development. As intentional teachers we are taught to observe, document, and analyze a child’s actions so we can better understand what the child is trying to “tell” us through their behavior. Behavior is a form of communication. Any challenging behavior that occurs over and over, is happening for a reason. If you can find the “pattern” in the behavior, you can figure out how to redirect or even stop the challenging behavior.

How do I find the patterns?

To be most effective, it is vital that we record what we see and hear as accurately and objectively as possible. No matter which observation method, tool or technique is used (e.g. Event Sampling, Frequency Counts, Checklists or Technology), once we have gathered a considerable amount of data we will need to interpret and reflect on the observation evidence so that we can plan for the next step. Finding the patterns can be instrumental in planning curriculum, setting up the environment with appropriate materials, and creating social situations that are suitable for the child’s temperament.

|

|

Think About It…Patterns If Wyatt is consistently observed going to the sandbox to play with dinosaurs during outside play, what does this tell you? What is the pattern? Is Wyatt interacting with other children? How is Wyatt using the dinosaurs? How can you use this information to support Wyatt during inside play? Here are a few ideas: To create curriculum : To encourage the child to go into the art center, knowing that he likes dinosaurs, I might lay down some butcher paint on a table, put a variety of dinosaurs out on the table, and add some trays with various colors of paint. To arrange the environment : Looking at my centers, I might add books and pictures about dinosaurs, and I might add materials that could be used in conjunction with dinosaurs. To support social development: I noticed Wyatt played by himself on several observations. I may need to do some follow up observations to see if Wyatt is initiating conversations, taking turns, joining in play with others or playing alone. As you can see these are just a few suggestions. What ideas did you come up with? As we monitor children in our class, we are gathering information so that we can create a space where each child’s individual personality, learning strengths, needs, and interests are all taken into account. Whether the child has a disability, delay or impairment or is developing at a typical pace, finding their unique pattern will help us provide suitable accommodations |

What is a Red Flag?

If, while monitoring a child’s development, a “red flag” is identified, it is the teacher’s responsibility to inform the family, in a timely manner, about their child’s developmental progress. First, the teacher and family would arrange a meeting to discuss what has been observed and documented. At the meeting, the teacher and family would share their perspectives about the child’s behavior, practices, mannerisms, routines and skill sets. There would be time to ask questions and clarify concerns, and a plan of action would be developed. It is likely that various adjustments to the environment would be suggested to meet the individual child’s needs, and ideas on how to tailor social interactions with peers would be discussed. With a plan in place, the teacher would continue to monitor the child. If after a few weeks there was no significant change or improvement, the teacher may then recommend that the child be formally screened and evaluated by a professional (e.g. a pediatrician, behavioral psychologist or a speech pathologist).

The Process of Screening and Evaluating

Who can screen and evaluate children? Doctors, pediatricians, speech pathologists, behaviorists, Screenings and evaluations are more formal than monitoring. Developmental screening takes a closer look at how a child is developing using brief tests. Your child will get a brief test, or you will complete a questionnaire about your child. The tools used for developmental and behavioral screening are formal questionnaires or checklists based on research that ask questions about a child’s development, including language, movement, thinking, behavior, and emotions.

Developmental screenings are cost effective and can be used to assess a large number of children in a relatively short period of time. There are screenings to assess a child’s hearing and vision, and to detect notable developmental delays. Screenings can also address some common questions and concerns that teachers, and parents alike, may have regarding a child’s academic progress. For example, when a teacher wonders why a child is behaving in such a way, they will want to observe a child’s social interactions and document how often certain behaviors occur. Similarly, when a parent voices a concern that their child is not talking in complete sentences the way their older child did at that same age. The teacher will want to listen and record the child’s conversations and track their language development.

Developmental Delays – is the condition of a child being less developed mentally or physically than is normal for their age.

Developmental Disabilities – According to the CDC, developmental disabilities are a group of conditions due to an impairment in physical, learning, language, or behavior areas. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may impact day-to-day functioning, and usually last throughout a person’s lifetime. Some noted disabilities include:

- ADHD

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Cerebral Palsy

- Hearing Loss

- Vision Impairment

- Learning Disability

- Intellectual Disability [35]

The Practice of Screening Young Children

To quickly capture a snapshot of a child’s overall development, early caregivers and teachers can select from several observation tools to observe and document a child’s play, learning, growth and development. Systematic and routine observations, made by knowledgeable and responsive teachers, ensure that children are receiving the quality care and support they deserve. Several observation tools and techniques can be used by teachers to screen a child’s development. Because each technique and tool provides limited observation data, it is suggested that teachers use a combination of tools and techniques to gather a full panoramic perspective of a child’s development. Here are some guidelines:

- Monitoring cannot capture the complete developmental range and capabilities of children, but can provide a general overview

- Monitoring can only indicate the possible presence of a developmental delay and cannot definitively identify the nature or extent of a disability

- Not all children with or at risk for delays can be identified

- Some children who are red-flagged may not have any actual delays or disabilities; they may be considered “exceptional” or “gifted”

- Children develop at different paces and may achieve milestones at various rates

Tools and Techniques to Monitor and Screen Children’s Development

Let’s briefly review some of the options more commonly used to monitor children’s development.

Developmental Milestone Checklists and Charts

There are many factors that can influence a child’s development: genetics, gender, social interactions, personal experiences, temperaments and the environment. It is critical that educators understand what is “typical” before they can consider what is “atypical.” Developmental Milestones provide a clear guideline as to what children should be able to do at set age ranges. However, it is important to note that each child in your classroom develops at their own individualized pace, and they will reach certain milestones at various times within the age range.

Developmental Milestone Charts are essential when setting up your classroom environments. Once you know what skills children should be able to do at specific ages, you can then plan developmentally appropriate learning goals, and you can set up your classroom environment with age appropriate materials. Developmental Milestone Charts are also extremely useful to teachers and parents when guiding behaviors. In order to set realistic expectations for children, it is suggested that teachers and parents review all ages and stages of development to understand how milestones evolve. Not only do skills build upon each other, they lay a foundation for the next milestone that’s to come. Developmental Milestone Charts are usually organized into 4 Domains: Physical, Cognitive, Language, and Social -Emotional.

Table 4.1 - Gross Motor Milestones from 2 Months to 2 Years [36]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

2 months |

|

|

4 months |

|

|

6 months |

|

|

9 months |

|

|

1 year |

|

|

18 months |

|

|

2 years |

|

Table 4.2 - Fine Motor Milestones from 2 Months to 2 Years [37]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

2 months |

|

|

4 months |

|

|

6 months |

|

|

9 months |

|

|

1 year |

|

|

18 months |

|

|

2 years |

|

Table 4.3 - Cognitive Milestones from 2 Months to 2 Years [38]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

2 months |

|

|

4 months |

|

|

6 months |

|

|

9 months |

|

|

1 year |

|

|

18 months |

|

|

2 years |

|

Table 4.4 - Language Milestones from 2 Months to 2 Years [39]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do By This Age |

|

2 months |

|

|

4 months |

|

|

6 months |

|

|

9 months |

|

|

1 year |

|

|

18 months |

|

|

2 years |

|

Table 4.5 - Social and Emotional Milestones from 2 Months to 2 Years [40]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do By This Age |

|

2 months |

|

|

4 months |

|

|

6 months |

|

|

9 months |

|

|

1 year |

|

|

18 months |

|

|

2 years |

|

Table 4.6 - Gross Motor Milestones from 3 Years to 5 Years [41]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Table 4.7 - Fine Motor Milestones from 3 Years to 5 Years [42]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Table 4.8 - Cognitive Milestones from 3 Years to 5 Years [43]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Table 4.9 - Language Milestones from 3 Years to 5 Years [44]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do By This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Table 4.10 - Social and Emotional Milestones from 3 Years to 5 Years [45]

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Time Sampling or Frequency Counts

When a teacher wants to know how often or how infrequent a behavior is occurring, they will use a Frequency Count to track a child’s behavior during a specific timeframe. This technique can help teachers track a child’s social interactions, play preferences, temperamental traits, aggressive behaviors, and activity interests.

Checklists

When a teacher wants to look at a child’s overall development, checklists can be a very useful tool to determine the presence or absence of a particular skill, milestone or behavior. Teachers will observe children during play times, circle times and centers, and will check-off the skills and behaviors as they are observed. Checklists help to determine which developmental skills have been mastered, which skills are emerging, and which skills have yet to be learned.

Technology

Teachers can use video recorders, cameras and tape recorders to record children while they are actively playing. This is an ideal method for capturing authentic quotes and work samples. Information gathered by way of technology can also be used with other screening tools and techniques as supporting evidence. (Note: it is important to be aware of center policies and procedures regarding proper consent before photographing or taping a child).

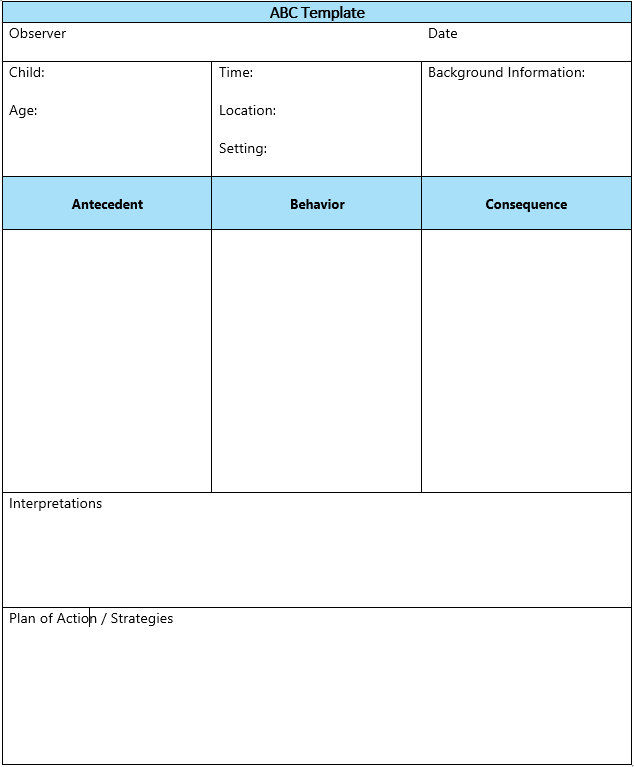

Event Sampling and the ABC Technique

When an incident occurs, we may wonder what triggered that behavior. The Event Sampling or ABC technique helps us to identify the social interactions and environmental situations that may cause children to react in certain ways. If we are to reinforce someone’s positive behavior, or change someone’s negative behavior, we must first try to understand what might be causing that particular behavior. With an ABC Analysis, the observer is looking for and tracking a specific behavior . More than the behavior itself, the observer wants to understand what is causing the behavior – this is antecedent. The antecedent happens before the behavior. It is believed that if the observer can find the “triggers” that might be leading up to or causing the challenging behavior, then potential strategies can be planned to alter, redirect or end the challenging behavior. In addition to uncovering the antecedent, what happens after the behavior is just as important, this is the “consequence.” How a child is treated after the incident or challenging behavior can create a positive or negative reinforcement pattern. In short, the ABC technique tells a brief story of what is happening before, during, and after a noted behavior.

The ABC observation method requires some training and practice. The observer must practice being neutral and free of bias, judgement and assumption in order to collect and record objective evidence and to portray an accurate picture. Although it may be uncomfortable to admit, certain behaviors can frustrate a teacher. If the teacher observes a child while feeling frustrated or annoyed, this can possibly taint the observation data. It is important to record just the facts. And to review the whole situation before making any premature assumptions.

Collecting your data

If you have a concern about a child’s behavior or if you have noticed a time when a child’s behavior has been rather disruptive, you will schedule a planned observation. For this type of observation, you can either video record the child in classroom environment, or you can take observation notes using a Running Record or Anecdotal Record technique. To find a consistent pattern, it is best to tape or write down your observations for several days to find a true and consistent pattern. To document your observations, include the child’s name, date, time, setting, and context. Observe and write down everything you see and hear before, during and after the noted behavior.

Organizing your data

Divide a piece of paper into 3 sections: A – for Antecedent; B – for Behavior; and C- for Consequence. Using your observation notes you will organize the information you collected into the proper sections. As you record the observation evidence, remember to report just the facts as objectively as possible. Afterwards, you will interpret the information and look for patterns. For example, did you find any “triggers” before the behavior occurred? What kind of “reinforcement” did the child receive after the behavior? What are some possible strategies you can try to minimize or redirect the challenging behavior? Do you need to make environmental changes? Are their social interactions that need to be further monitored? With challenging behaviors, there is not a quick fix or an easy answer. You must follow through and continue to observe the child to see if your strategies are working.

|

|

Pin It! The ABC Method (A) Antecedent : Right before an incident or challenging behavior occurs, something is going on to lead up to or prompt the actual incident or behavior. For example, one day during lunch Susie spills her milk (this behavior has happened several times before). Rather than focusing solely on the incident itself (Susie spilling the milk), look to see what was going on before the incident. More specifically, look to see if Susie was in a hurry to finish her snack so she could go outside and play? Was Susie being silly? Which hand was Susie using – is this her dominant hand? Is the milk pitcher too big for Susie to manipulate? (B) Behavior: This refers to the measurable or observable actions. In this case, it is Susie spilling the milk. (C) Consequence: The consequence is what happens directly after the behavior. For example, right after Susie spilt the milk, did you yell at her or display an unhappy or disgusted look? Did Susie cry? Did Susie attempt to clean up the milk? Did another child try to help Susie? Watch this video for more information on the ABC model : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVKb_BXEp5U |

The Practice of Screening and Evaluating

Beyond monitoring, once a child has been “red-flagged” they will need to be assessed by a professional who will use a formal diagnostic tool to evaluate the child’s development. Families can request that a formal screening be conducted at the local elementary school if their child is 3 to 5 years old. Depending upon the nature of the red flag, there are a battery of tools that can be used to evaluate a child’s development. Here are some guidelines:

- Screenings are designed to be brief (30 minutes or less)

- A more comprehensive assessment and formal evaluation must be conducted by a professional in order to confirm or disconfirm any red flags that were raised during the initial monitoring or screening process

- Families must be treated with dignity, sensitivity and compassion while their child is going through the screening process

- Use a screening tool from a reputable publishing company

Screening Instruments and Evaluation Tests

The instruments listed below are merely a sample of some of the developmental and academic screening tests that are widely used.

Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ), Brookes Publishing Company (available in Spanish, French, and Korean)

Battelle Developmental Inventory Screening Test, Riverside Publishing

Developmental Indicators for Assessment of Learning (DIAL) III, Pearson Assessments (includes Spanish materials)

Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS), University of Oregon Center on Teaching and Learning

Early Screening Inventory-Revised (ESI-R), Pearson Early Learning (includes separate scoring for preschool and kindergarten) [46]

|

|

Pin It! Reliability and Validity Defined Reliability means that the scores on the tool will be stable regardless of when the tool is administered, where it is administered, and who is administering it. Reliability answers the question: Is the tool producing consistent information across different circumstances? Reliability provides assurance that comparable information will be obtained from the tool across different situations. Validity means that the scores on the tool accurately capture what the tool is meant to capture in terms of content. Validity answers the question: Is the tool assessing what it is supposed to assess? |