5.3: Adolescence - Developing Independence and Identity

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 40777

- Anonymous

- LibreTexts

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the physical and cognitive changes that occur for boys and girls during adolescence.

- Explain how adolescents develop a sense of morality and of self-identity.

Adolescence is defined as the years between the onset of puberty and the beginning of adulthood. In the past, when people were likely to marry in their early 20s or younger, this period might have lasted only 10 years or less—starting roughly between ages 12 and 13 and ending by age 20, at which time the child got a job or went to work on the family farm, married, and started his or her own family. Today, children mature more slowly, move away from home at later ages, and maintain ties with their parents longer. For instance, children may go away to college but still receive financial support from parents, and they may come home on weekends or even to live for extended time periods. Thus the period between puberty and adulthood may well last into the late 20s, merging into adulthood itself. In fact, it is appropriate now to consider the period of adolescence and that of emerging adulthood (the ages between 18 and the middle or late 20s) together.

During adolescence, the child continues to grow physically, cognitively, and emotionally, changing from a child into an adult. The body grows rapidly in size and the sexual and reproductive organs become fully functional. At the same time, as adolescents develop more advanced patterns of reasoning and a stronger sense of self, they seek to forge their own identities, developing important attachments with people other than their parents. Particularly in Western societies, where the need to forge a new independence is critical (Baumeister & Tice, 1986; Twenge, 2006), this period can be stressful for many children, as it involves new emotions, the need to develop new social relationships, and an increasing sense of responsibility and independence.

Although adolescence can be a time of stress for many teenagers, most of them weather the trials and tribulations successfully. For example, the majority of adolescents experiment with alcohol sometime before high school graduation. Although many will have been drunk at least once, relatively few teenagers will develop long-lasting drinking problems or permit alcohol to adversely affect their school or personal relationships. Similarly, a great many teenagers break the law during adolescence, but very few young people develop criminal careers (Farrington, 1995). These facts do not, however, mean that using drugs or alcohol is a good idea. The use of recreational drugs can have substantial negative consequences, and the likelihood of these problems (including dependence, addiction, and even brain damage) is significantly greater for young adults who begin using drugs at an early age.

Physical Changes in Adolescence

Adolescence begins with the onset of puberty, a developmental period in which hormonal changes cause rapid physical alterations in the body, culminating in sexual maturity. Although the timing varies to some degree across cultures, the average age range for reaching puberty is between 9 and 14 years for girls and between 10 and 17 years for boys (Marshall & Tanner, 1986).

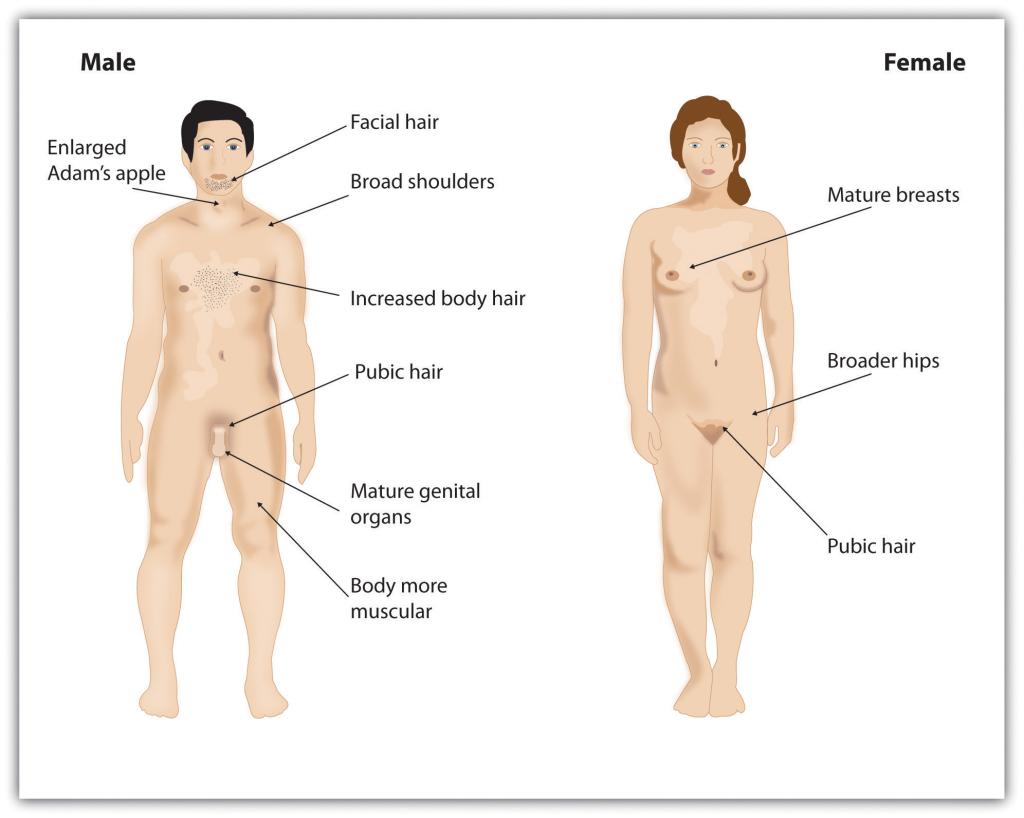

Puberty begins when the pituitary gland begins to stimulate the production of the male sex hormone testosterone in boys and the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone in girls. The release of these sex hormones triggers the development of the primary sex characteristics, the sex organs concerned with reproduction (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). These changes include the enlargement of the testicles and the penis in boys and the development of the ovaries, uterus, and vagina in girls. In addition, secondary sex characteristics (features that distinguish the two sexes from each other but are not involved in reproduction) are also developing, such as an enlarged Adam’s apple, a deeper voice, and pubic and underarm hair in boys and enlargement of the breasts, hips, and the appearance of pubic and underarm hair in girls (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). The enlargement of breasts is usually the first sign of puberty in girls and, on average, occurs between ages 10 and 12 (Marshall & Tanner, 1986). Boys typically begin to grow facial hair between ages 14 and 16, and both boys and girls experience a rapid growth spurt during this stage. The growth spurt for girls usually occurs earlier than that for boys, with some boys continuing to grow into their 20s.

A major milestone in puberty for girls is menarche, the first menstrual period, typically experienced at around 12 or 13 years of age (Anderson, Dannal, & Must, 2003). The age of menarche varies substantially and is determined by genetics, as well as by diet and lifestyle, since a certain amount of body fat is needed to attain menarche. Girls who are very slim, who engage in strenuous athletic activities, or who are malnourished may begin to menstruate later. Even after menstruation begins, girls whose level of body fat drops below the critical level may stop having their periods. The sequence of events for puberty is more predictable than the age at which they occur. Some girls may begin to grow pubic hair at age 10 but not attain menarche until age 15. In boys, facial hair may not appear until 10 years after the initial onset of puberty.

The timing of puberty in both boys and girls can have significant psychological consequences. Boys who mature earlier attain some social advantages because they are taller and stronger and, therefore, often more popular (Lynne, Graber, Nichols, Brooks-Gunn, & Botvin, 2007). At the same time, however, early-maturing boys are at greater risk for delinquency and are more likely than their peers to engage in antisocial behaviors, including drug and alcohol use, truancy, and precocious sexual activity. Girls who mature early may find their maturity stressful, particularly if they experience teasing or sexual harassment (Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2007; Pescovitz & Walvoord, 2007). Early-maturing girls are also more likely to have emotional problems, a lower self-image, and higher rates of depression, anxiety, and disordered eating than their peers (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996).

Cognitive Development in Adolescence

Although the most rapid cognitive changes occur during childhood, the brain continues to develop throughout adolescence, and even into the 20s (Weinberger, Elvevåg, & Giedd, 2005). During adolescence, the brain continues to form new neural connections, but also casts off unused neurons and connections (Blakemore, 2008). As teenagers mature, the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for reasoning, planning, and problem solving, also continues to develop (Goldberg, 2001). And myelin, the fatty tissue that forms around axons and neurons and helps speed transmissions between different regions of the brain, also continues to grow (Rapoport et al., 1999).

Adolescents often seem to act impulsively, rather than thoughtfully, and this may be in part because the development of the prefrontal cortex is, in general, slower than the development of the emotional parts of the brain, including the limbic system (Blakemore, 2008). Furthermore, the hormonal surge that is associated with puberty, which primarily influences emotional responses, may create strong emotions and lead to impulsive behavior. It has been hypothesized that adolescents may engage in risky behavior, such as smoking, drug use, dangerous driving, and unprotected sex in part because they have not yet fully acquired the mental ability to curb impulsive behavior or to make entirely rational judgments (Steinberg, 2007).

The new cognitive abilities that are attained during adolescence may also give rise to new feelings of egocentrism, in which adolescents believe that they can do anything and that they know better than anyone else, including their parents (Elkind, 1978, p. 199). Teenagers are likely to be highly self-conscious, often creating an imaginary audience in which they feel that everyone is constantly watching them (Goossens, Beyers, Emmen, & van Aken, 2002). Because teens think so much about themselves, they mistakenly believe that others must be thinking about them, too (Rycek, Stuhr, McDermott, Benker, & Swartz, 1998). It is no wonder that everything a teen’s parents do suddenly feels embarrassing to them when they are in public.

Social Development in Adolescence

Some of the most important changes that occur during adolescence involve the further development of the self-concept and the development of new attachments. Whereas young children are most strongly attached to their parents, the important attachments of adolescents move increasingly away from parents and increasingly toward peers (Harris, 1998). As a result, parents’ influence diminishes at this stage.

According to Erikson (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)), the main social task of the adolescent is the search for a unique identity—the ability to answer the question, “Who am I?” In the search for identity, the adolescent may experience role confusion in which he or she is balancing or choosing among identities, taking on negative or undesirable identities, or temporarily giving up looking for an identity altogether if things are not going well.

One approach to assessing identity development was proposed by James Marcia (1980). In his approach, adolescents are asked questions regarding their exploration of and commitment to issues related to occupation, politics, religion, and sexual behavior. The responses to the questions allow the researchers to classify the adolescent into one of four identity categories (Table \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

| Identity-diffusion status | The individual does not have firm commitments regarding the issues in question and is not making progress toward them. |

| Foreclosure status | The individual has not engaged in any identity experimentation and has established an identity based on the choices or values of others. |

| Moratorium status | The individual is exploring various choices but has not yet made a clear commitment to any of them. |

| Identity-achievement status | The individual has attained a coherent and committed identity based on personal decisions. |

Source: Adapted from Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. Handbook of adolescent psychology, 5, 145–160.

Studies assessing how teens pass through Marcia’s stages show that, although most teens eventually succeed in developing a stable identity, the path to it is not always easy and there are many routes that can be taken. Some teens may simply adopt the beliefs of their parents or the first role that is offered to them, perhaps at the expense of searching for other, more promising possibilities (foreclosure status). Other teens may spend years trying on different possible identities (moratorium status) before finally choosing one.

To help them work through the process of developing an identity, teenagers may well try out different identities in different social situations. They may maintain one identity at home and a different type of persona when they are with their peers. Eventually, most teenagers do integrate the different possibilities into a single self-concept and a comfortable sense of identity (identity-achievement status).

For teenagers, the peer group provides valuable information about the self-concept. For instance, in response to the question “What were you like as a teenager? (e.g., cool, nerdy, awkward?),” posed on the website Answerbag, one teenager replied in this way:

Responses like this one demonstrate the extent to which adolescents are developing their self-concepts and self-identities and how they rely on peers to help them do that. The writer here is trying out several (perhaps conflicting) identities, and the identities any teen experiments with are defined by the group the person chooses to be a part of. The friendship groups (cliques, crowds, or gangs) that are such an important part of the adolescent experience allow the young adult to try out different identities, and these groups provide a sense of belonging and acceptance (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). A big part of what the adolescent is learning is social identity, the part of the self-concept that is derived from one’s group memberships. Adolescents define their social identities according to how they are similar to and differ from others, finding meaning in the sports, religious, school, gender, and ethnic categories they belong to.

Developing Moral Reasoning: Kohlberg’s Theory

The independence that comes with adolescence requires independent thinking as well as the development of morality—standards of behavior that are generally agreed on within a culture to be right or proper. Just as Piaget believed that children’s cognitive development follows specific patterns, Lawrence Kohlberg (1984) argued that children learn their moral values through active thinking and reasoning, and that moral development follows a series of stages. To study moral development, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to children, teenagers, and adults, such as the following:

A man’s wife is dying of cancer and there is only one drug that can save her. The only place to get the drug is at the store of a pharmacist who is known to overcharge people for drugs. The man can only pay $1,000, but the pharmacist wants $2,000, and refuses to sell it to him for less, or to let him pay later. Desperate, the man later breaks into the pharmacy and steals the medicine. Should he have done that? Was it right or wrong? Why? (Kohlberg, 1984)

Video Clip: People Being Interviewed About Kohlberg’s Stages. https://youtu.be/zY4etXWYS84

As you can see in Table \(\PageIndex{5}\), Kohlberg concluded, on the basis of their responses to the moral questions, that, as children develop intellectually, they pass through three stages of moral thinking: the preconventional level, the conventional level, and the postconventional level.

| Age | Moral Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Young children | Preconventional morality | Until about the age of 9, children, focus on self-interest. At this stage, punishment is avoided and rewards are sought. A person at this level will argue, “The man shouldn’t steal the drug, as he may get caught and go to jail.” |

| Older children, adolescents, most adults | Conventional morality | By early adolescence, the child begins to care about how situational outcomes impact others and wants to please and be accepted. At this developmental phase, people are able to value the good that can be derived from holding to social norms in the form of laws or less formalized rules. For example, a person at this level may say, “He should not steal the drug, as everyone will see him as a thief, and his wife, who needs the drug, wouldn’t want to be cured because of thievery,” or, “No matter what, he should obey the law because stealing is a crime.” |

| Many adults | Postconventional morality | At this stage, individuals employ abstract reasoning to justify behaviors. Moral behavior is based on self-chosen ethical principles that are generally comprehensive and universal, such as justice, dignity, and equality. Someone with self-chosen principles may say, “The man should steal the drug to cure his wife and then tell the authorities that he has done so. He may have to pay a penalty, but at least he has saved a human life.” |

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment and social rules and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, children may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems, but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms (such as respect for authority) may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). And there is frequently little correlation between how children score on the moral stages and how they behave in real life.

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of boys better than it describes that of girls. Carol Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence that boys and girls score differently on Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000).If you don’t believe this, ask yourself when you last got a thank-you note from a man.

Key Takeaways

- Adolescence is the period of time between the onset of puberty and emerging adulthood.

- Emerging adulthood is the period from age 18 years until the mid-20s in which young people begin to form bonds outside the family, attend college, and find work. Even so, they tend not to be fully independent and have not taken on all the responsibilities of adulthood. This stage is most prevalent in Western cultures.

- Puberty is a developmental period in which hormonal changes cause rapid physical alterations in the body.

- The cerebral cortex continues to develop during adolescence and early adulthood, enabling improved reasoning, judgment, impulse control, and long-term planning.

- A defining aspect of adolescence is the development of a consistent and committed self-identity. The process of developing an identity can take time but most adolescents succeed in developing a stable identity.

- Kohlberg’s theory proposes that moral reasoning is divided into the following stages: preconventional morality, conventional morality, and postconventional morality.

- Kohlberg’s theory of morality has been expanded and challenged, particularly by Gilligan, who has focused on differences in morality between boys and girls.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Based on what you learned in this chapter, do you think that people should be allowed to drive at age 16? Why or why not? At what age do you think they should be allowed to vote and to drink alcohol?

- Think about your experiences in high school. What sort of cliques or crowds were there? How did people express their identities in these groups? How did you use your groups to define yourself and develop your own identity?

References

Anderson, S. E., Dannal, G. E., & Must, A. (2003). Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: Results from two nationally representative surveys of U.S. girls studied 25 years apart. Pediatrics, 111, 844–850.

Answerbag. (2007, March 20). What were you like as a teenager? (e.g., cool, nerdy, awkward?). Retrieved from http://www.answerbag.com/q_view/171753

Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1986). How adolescence became the struggle for self: A historical transformation of psychological development. In J. Suls & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 3, pp. 183–201). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Blakemore, S. J. (2008). Development of the social brain during adolescence. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 40–49.

Elkind, D. (1978). The child’s reality: Three developmental themes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Farrington, D. P. (1995). The challenge of teenage antisocial behavior. In M. Rutter & M. E. Rutter (Eds.), Psychosocial disturbances in young people: Challenges for prevention (pp. 83–130). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ge, X., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (1996). Coming of age too early: Pubertal influences on girls’ vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Development, 67(6), 3386–3400.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goldberg, E. (2001). The executive brain: Frontal lobes and the civilized mind. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Goossens, L., Beyers, W., Emmen, M., & van Aken, M. (2002). The imaginary audience and personal fable: Factor analyses and concurrent validity of the “new look” measures. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(2), 193–215.

Harris, J. (1998), The nurture assumption—Why children turn out the way they do. New York, NY: Free Press.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: Essays on moral development (Vol. 2, p. 200). San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Jaffee, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2000). Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 703–726.

Lynne, S. D., Graber, J. A., Nichols, T. R., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Botvin, G. J. (2007). Links between pubertal timing, peer influences, and externalizing behaviors among urban students followed through middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 181.e7–181.e13 (p. 198).

Mendle, J., Turkheimer, E., & Emery, R. E. (2007). Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review, 27, 151–171; Pescovitz, O. H., & Walvoord, E. C. (2007). When puberty is precocious: Scientific and clinical aspects. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 5, 145–160.

Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1986). Puberty. In F. Falkner & J. M. Tanner (Eds.), Human growth: A comprehensive treatise (2nd ed., pp. 171–209). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Rapoport, J. L., Giedd, J. N., Blumenthal, J., Hamburger, S., Jeffries, N., Fernandez, T.,…Evans, A. (1999). Progressive cortical change during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia: A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7), 649–654.

Rest, J. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 571–645). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Rycek, R. F., Stuhr, S. L., Mcdermott, J., Benker, J., & Swartz, M. D. (1998). Adolescent egocentrism and cognitive functioning during late adolescence. Adolescence, 33, 746–750.

Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 55–59.

Turiel, E. (1998). The development of morality. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 863–932). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—and more miserable than ever before. New York, NY: Free Press.

Weinberger, D. R., Elvevåg, B., & Giedd, J. N. (2005). The adolescent brain: A work in progress. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Retrieved from www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/BRAIN.pdf