12.1.2: First Africa, Then the World

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 136457

What enabled modern Homo sapiens to expand its range further in 300,000 years than Homo erectus did in 1.5 million years? The key is the set of derived biological traits from the last section. The gracile frame and neurological anatomy allowed modern humans to survive and even flourish in the vastly different environments they encountered. Based on multiple types of evidence, the source of all of these modern humans, including all of us today, was Africa.

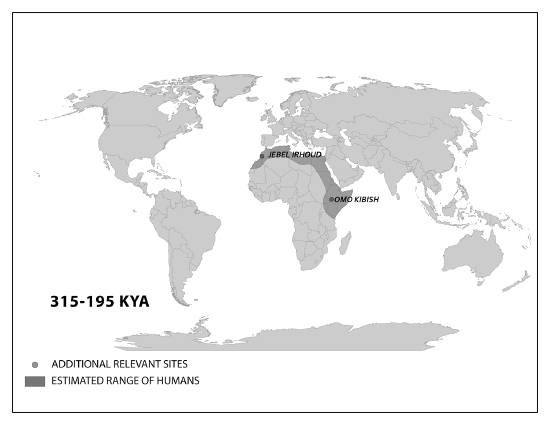

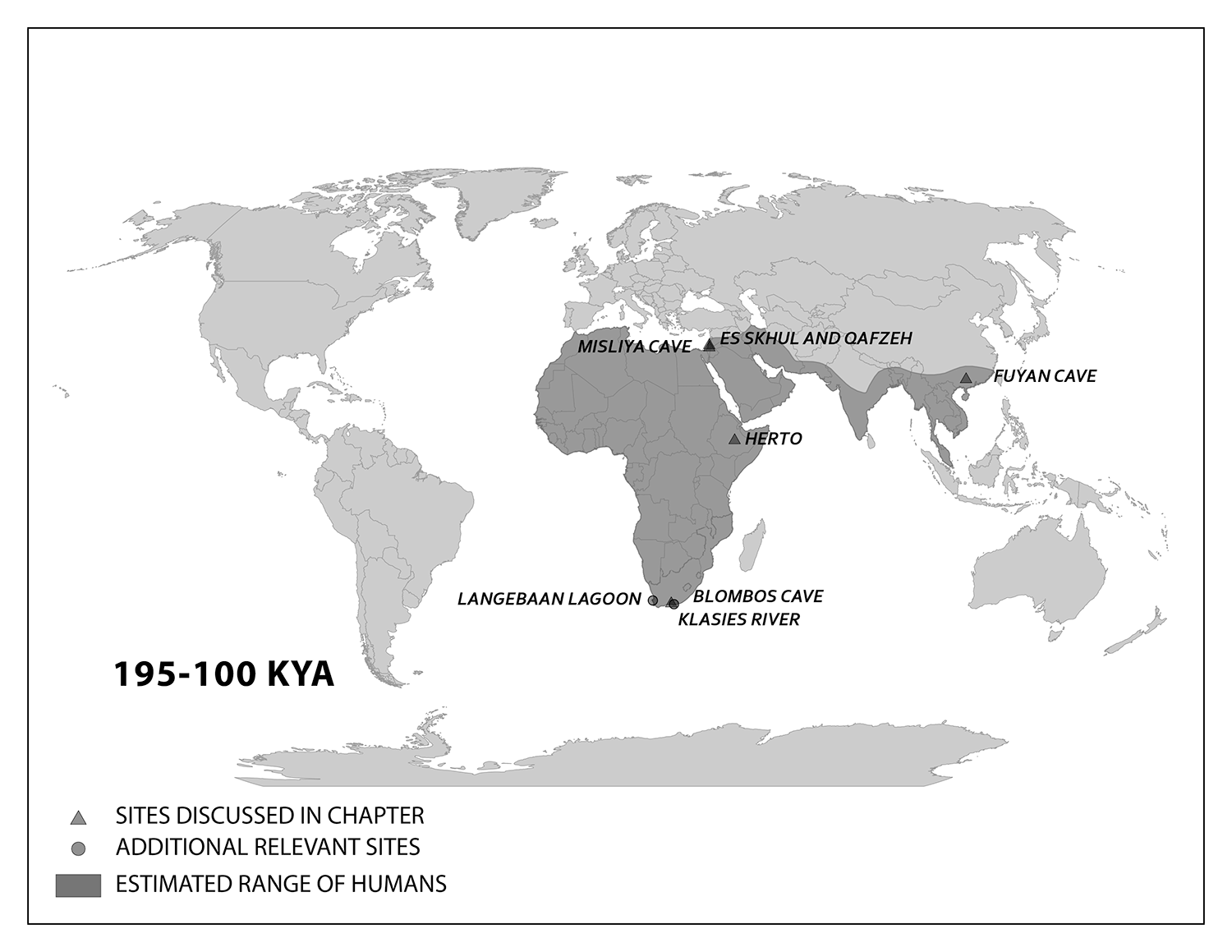

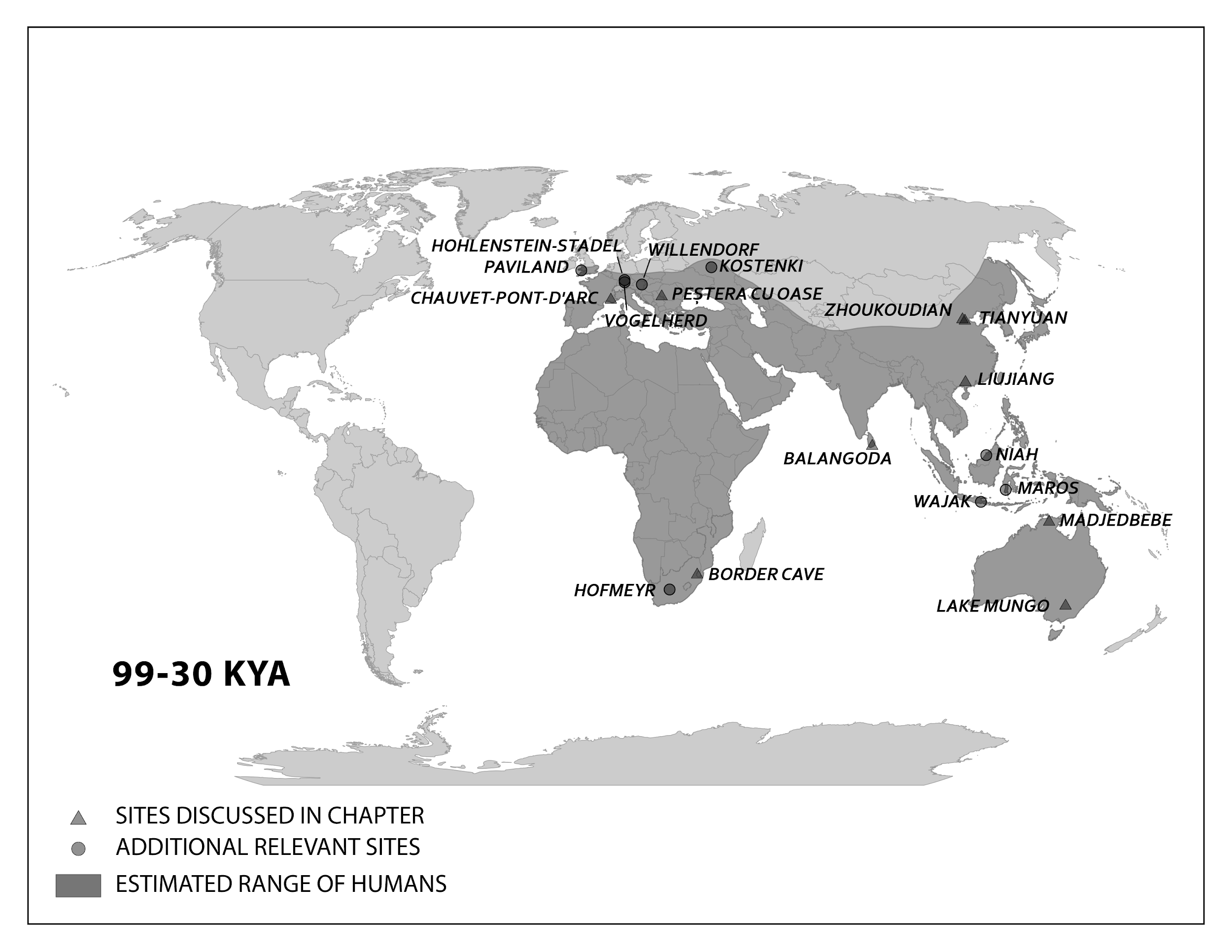

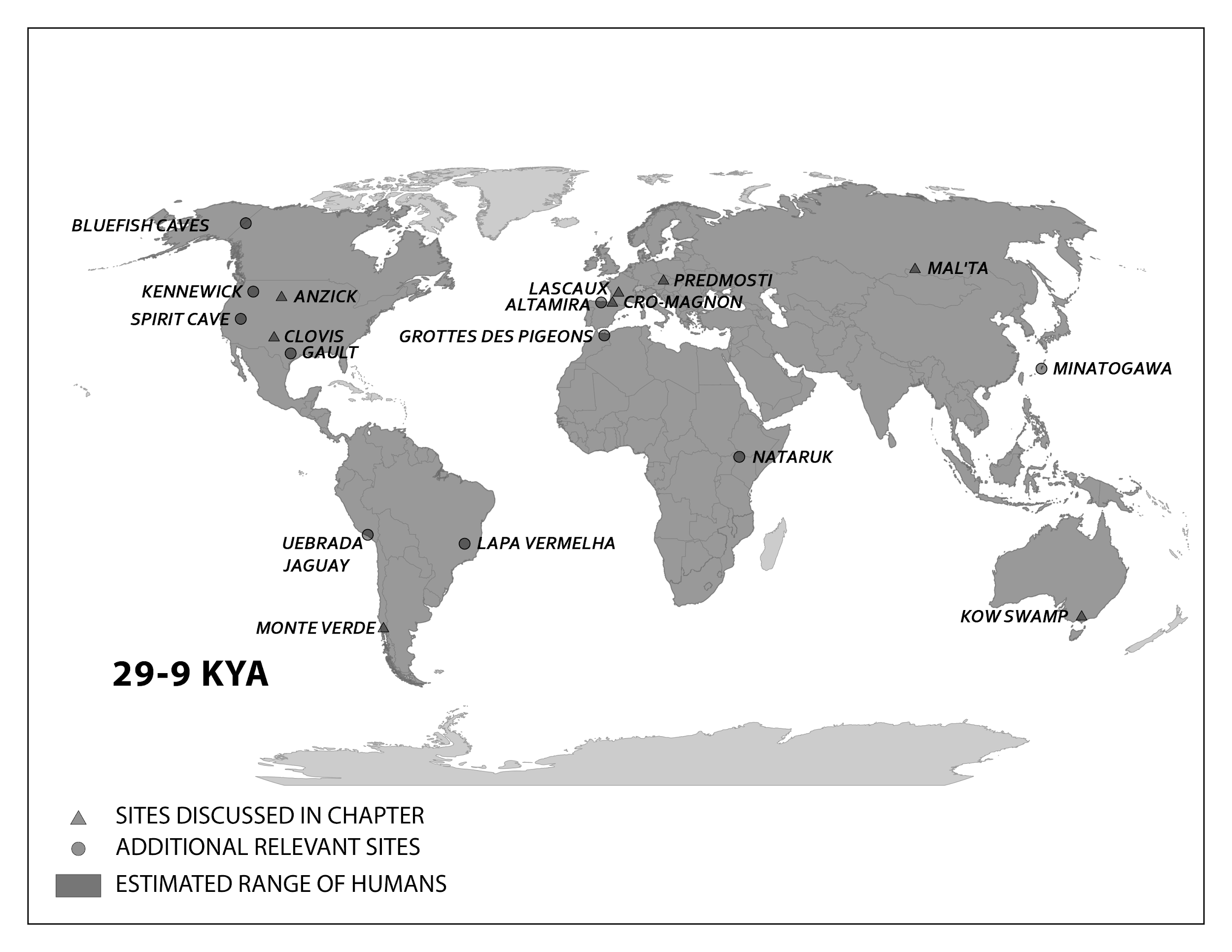

This section traces the origin of modern Homo sapiens and the massive expansion of our species across all of the continents except Antarctica by 12,000 years ago. While modern Homo sapiens first shared geography with archaic humans, modern humans eventually spread into lands where no human had gone before. Starting with the first-known modern Homo sapiens, around 315,000 years ago, we will follow our species from a time called the Middle Pleistocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene. Culturally, we will trace developments from the Middle Stone Age through the transition around 50,000 years ago to the Later Stone Age, when cultural complexity quickly grew with both technology and artistry. We will end this section right before the next big cultural change, called the Neolithic Revolution.

A few notes on this part of the chapter: It is organized from past to present when possible, though a lot happens simultaneously to our species in that time. Figure 12.5 shows the broad routes that our species took expanding around the world. I encourage you to make your own timeline with the dates in this part to see the overall trends. References are provided to the research leading to the information on key finds. Search for these scientific papers online to see how researchers reach the conclusions presented here.

The Start of Modern Homo sapiens in Africa

We start with the ample fossil evidence supporting the theory that modern humans originated in Africa during the Middle Pleistocene, having evolved from African archaic Homo sapiens. The earliest dated fossils considered to be modern actually have a mosaic of archaic and modern traits, showing the complex changes from one type to the other. Experts have various names for these transitional fossils, such as or Early Anatomically Modern Humans. However they are labeled, the presence of some modern traits means that they illustrate the origin of the modern type. Three particularly informative sites with fossils of the earliest modern Homo sapiens are Jebel Irhoud, Omo, and Herto.

Recall from the start of the chapter that the most recent finds at Jebel Irhoud are now the oldest dated fossils that exhibit the traits of modern Homo sapiens. Besides Irhoud 10, the cranium that was dated to 315,000 years ago (Hublin et al. 2017; Richter et al. 2017), there were other fossils found in the same deposit that we now know are from the same time period. In total there are at least five individuals, representing life stages from childhood to adulthood. These fossils form an image of high variation in skeletal traits. For example, the skull named Irhoud 1 has a primitive brow ridge, while Irhoud 2 and Irhoud 10 do not (Figure 12.6). The braincases are lower than what is seen in the modern humans of today but higher than in archaic Homo sapiens. The teeth also have a mix of archaic and modern traits that defy clear categorization into either group.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Composite rendering of the Jebel Irhoud hominin based on micro-CT scans of multiple fossils from the site. The facial structure is within the modern human range, while the braincase is between the archaic and modern shapes.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Composite rendering of the Jebel Irhoud hominin based on micro-CT scans of multiple fossils from the site. The facial structure is within the modern human range, while the braincase is between the archaic and modern shapes.Research separated by nearly four decades uncovered fossils and artifacts from the Kibish Formation in the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia. These Omo Kibish hominins were represented by braincases and fragmented postcranial bones of three individuals found kilometers apart, dating back to 195,000 years ago (Day 1969; McDougall, Brown, and Fleagle 2005). One interesting finding was the variation in braincase size between the two more-complete specimens: While the individual now named Omo I had a more globular dome, Omo II had an archaic-style long and low cranium. In more recent fieldwork, an informative section of the Omo I pelvis was found in a re-excavation in 2001. Analysis by Ashley S. Hammond and colleagues (2017) found that the measurements and observations were in line with modern Homo sapiens, although larger in absolute size and robusticity.

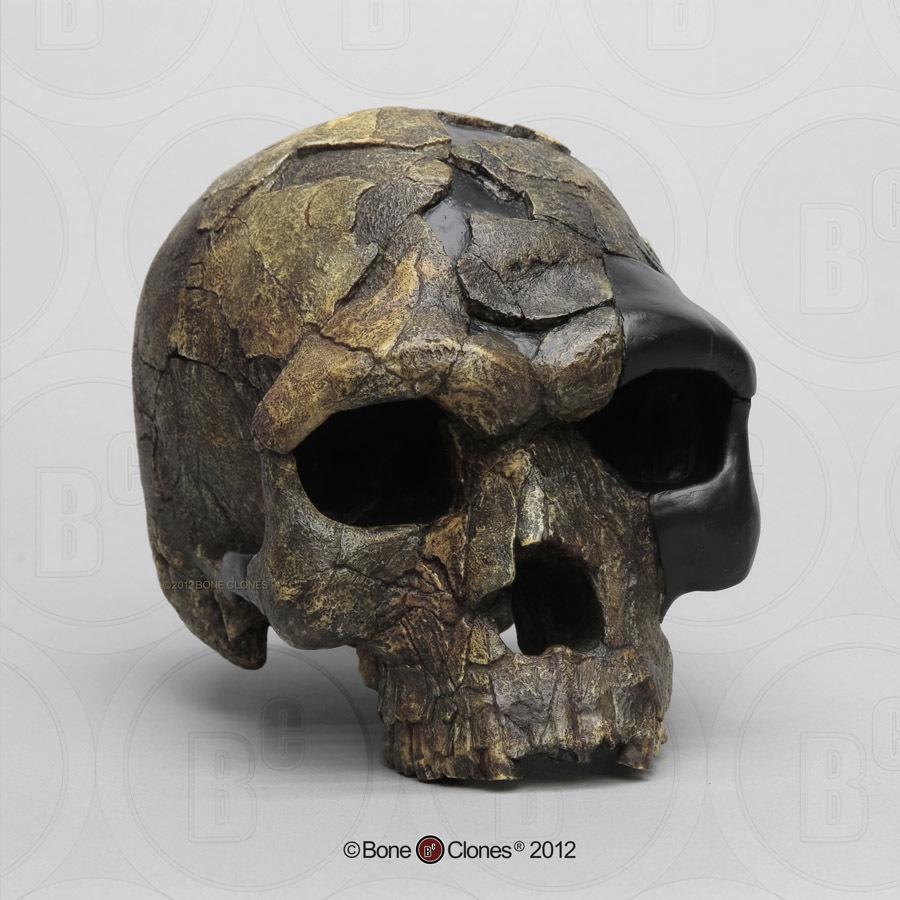

Also in Ethiopia, a team led by Tim White (2003) excavated numerous fossils at Herto. There were fossilized crania of two adults and a child, along with fragments of more individuals. The dates ranged between 160,000 and 154,000 years ago. The skeletal traits and stone tool assemblage were both intermediate between the archaic and modern types. Features reminiscent of modern humans included a tall braincase and thinner zygomatic (cheek) bones than those of archaic humans (Figure 12.7). Still, some archaic traits persisted in the Herto fossils. Looking at the face, the supraorbital tori were still prominent. The cranium included an angled occipital bone and was longer than in present-day modern Homo sapiens. Statistical analysis by other research teams concluded that at least some cranial measurements fit just within the modern human range (McCarthy and Lucas 2014), favoring categorization with our own species.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): This model of the Herto cranium showing its mosaic of archaic and modern traits.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): This model of the Herto cranium showing its mosaic of archaic and modern traits.Summary of Early Modern H. sapiens in Africa

The combined fossil evidence paints a picture of diversity in geography and traits. Instead of evolving in just East Africa, the Jebel Irhoud find revealed that early modern Homo sapiens had a wide range across Middle Pleistocene Africa. The hypothesis that there was no single original home within Africa for our species is called African multiregionalism (Scerri et al. 2018). Supporting this explanation, fossils have different mosaics of archaic and modern traits in different places and even within the same area. The high level of diversity from just these fossils shows that the modern traits took separate paths toward the set we have today. The connections were convoluted, involving fluctuating gene flow among small groups of regional nomadic foragers across a large continent over a long time.

What about behavioral modernity? Jebel Irhoud, Omo, and Herto all bore Middle Stone Age tools of the same flaked style as archaic assemblages, even though they were separated by almost 150,000 years. The apparent stability in technology may be evidence that behavioral modernity was not so developed back then, though there was a high variety of tool types used throughout that time. No clear signs of art dating back this far have been found either. Other hypotheses not related to behavioral modernity could explain these observations. The tool set may have been suitable for thriving in Africa without further innovation. As for the lack of art, maybe works from that time were made with media that deteriorated or perhaps such works were removed by later humans.

While modern Homo sapiens lived across Africa, some members eventually left the continent. Generations of these pioneers entered environments far different from what their ancestors experienced in Africa. The next four sections cover evidence of modern Homo sapiens in other parts of the Old World and the evidence we have about what they did. We will check back with Africa later in the chapter to see what happened biologically and culturally on the home front amid the expansion.

Expansion into the Midd

le East and Asia

This section presents key finds showing where modern Homo sapiens went after the range of the species first extended out of Africa. These pioneers could have used two connections to the Middle East, or West Asia. From North Africa, they could have crossed the Sinai Peninsula and moved north to the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean. Finds in that region show an early modern human presence. Other finds support the Southern Dispersal model, with a crossing from East Africa to the southern Arabian Peninsula through the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. It is tempting to think of one momentous event in which people stepped off Africa and into the Middle East, never to look back. In reality, there were likely multiple waves of movement producing gene flow back and forth across these regions. The expanding modern human population could have thrived by using resources along the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula to South Asia, with side routes moving north along rivers. The maximum range of the species then grew across Asia as shown by evidence across the continent.

Modern Homo sapiens in the Middle East

Geographically, the Middle East is the ideal place for the African modern Homo sapiens population to inhabit upon expanding out of their home continent. In the Eastern Mediterranean coast of the Levant, there is a wealth of skeletal and material culture linked to modern Homo sapiens. Recent discoveries from Saudi Arabia further add to our view of human life just beyond Africa.

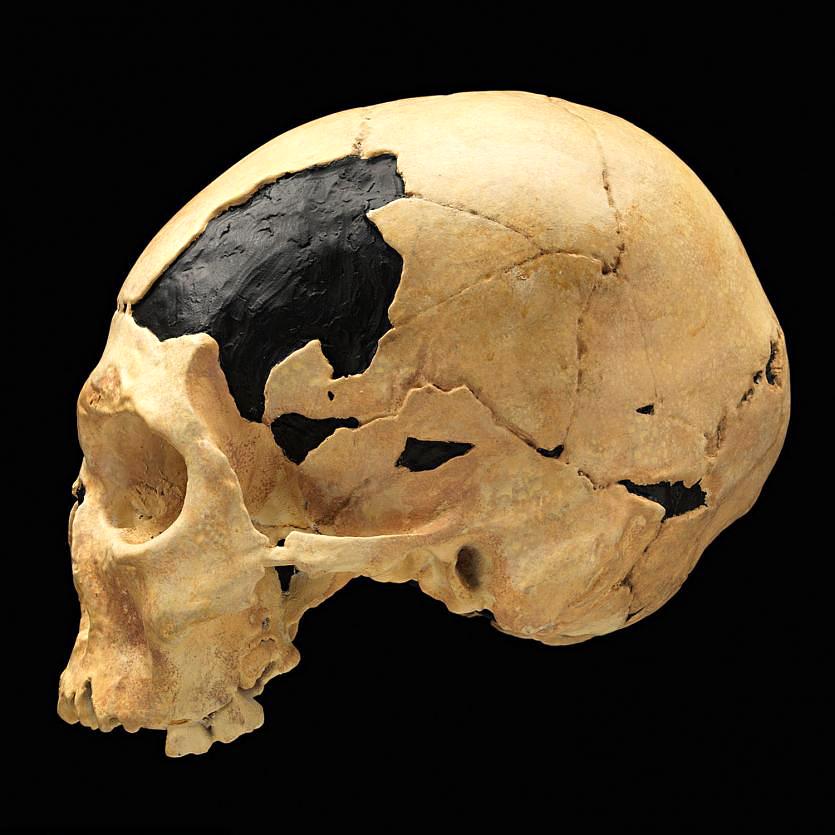

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): This Skhul V cranium model shows the sharp browridges. The contour of a marked occipital bun is barely visible from this angle.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): This Skhul V cranium model shows the sharp browridges. The contour of a marked occipital bun is barely visible from this angle.The Caves of Mount Carmel in present-day Israel have preserved skeletal remains and artifacts of modern Homo sapiens, the first-known group living outside Africa. The skeletal presence at Misliya Cave is represented by just part of the left upper jaw of one individual, but it is notable for being dated to a very early time, between 194,000 and 177,000 years ago (Hershkovitz et al. 2018). Later, from 120,000 to 90,000 years ago, fossils of multiple individuals across life stages were found in the caves of Es-Skhul and Qafzeh (Shea and Bar-Yosef 2005). The skeletons had many modern Homo sapiens traits, such as globular crania and more gracile postcranial bones when compared to Neanderthals. Still, there were some archaic traits. For example, the adult male Skhul V also possessed what researchers Daniel Lieberman, Osbjorn Pearson, and Kenneth Mowbray (2000) called marked or clear occipital bunning. Also, compared to later modern humans, the Mount Carmel people were more robust. Skhul V had a particularly impressive brow ridge that was short in height but sharply jutted forward above the eyes (Figure 12.8). The high level of preservation is due to the intentional burial of some of these people. Besides skeletal material, there are signs of artistic or symbolic behavior. For example, the adult male Skhul V had a boar’s jaw on his chest. Similarly, Qafzeh 11, a juvenile with healed cranial trauma, had an impressive deer antler rack placed over his torso (Figure 12.9) (Coqueugniot et al. 2014). Perforated seashells colored with ochre, mineral-based pigment, were also found in Qafzeh (Bar-Yosef Mayer, Vandermeersch, and Bar-Yosef 2009).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): This cast of the Qafzeh 11 burial shows the antler’s placement over the upper torso. The forearm bones appear to overlap the antler.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): This cast of the Qafzeh 11 burial shows the antler’s placement over the upper torso. The forearm bones appear to overlap the antler.One remaining question is, what happened to the modern humans of the Levant after 90,000 years ago? Another site attributed to our species did not appear in the region until 47,000 years ago. Competition with Neanderthals may have accounted for the disappearance of modern human occupation since the Neanderthal presence in the Levant lasted longer than the dates of the early modern Homo sapiens. John Shea and Ofer Bar-Yosef (2005) hypothesized that the Mount Carmel modern humans were an initial expansion from Africa but one that failed. Perhaps they could not succeed due to competition with the Neanderthals who had been there longer and had both cultural and biological adaptations to that environment.

Six-hundred kilometers from Mount Carmel, the fossil AW-1 from Al Wusta in Saudi Arabia was just one finger bone, but it greatly enhanced our view of modern Homo sapiens just outside Africa. Dating methods converged on a range between 130,000 and 90,000 years ago, overlapping the Skhul and Qafzeh range (Groucutt et al. 2018). The AW-1 bone and its associated stone tools added to evidence of many sites dotted throughout the Arabian Peninsula that contained stone tools but not skeletal remains.

Modern Homo sapiens of China

A long history of paleoanthropology in China has found ample evidence of modern human presence. Four notable sites are the caves at Fuyan, Liujiang, Tianyuan, and Zhoukoudian. In the distant past, these caves would have been at least seasonal shelters that unintentionally preserved evidence of human presence for modern researchers to discover.

At Fuyan Cave in Southern China, paleoanthropologists found 47 adult teeth associated with cave formations dated to between 120,000 and 80,000 years ago (Liu et al. 2015). It is currently the oldest-known modern human site in China, though other researchers question the validity of the date range (Michel et al. 2016). The teeth have the small size and gracile features of modern Homo sapiens dentition. No lithics have been found in Fuyan Cave.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The Liujiang cranium shows the tall forehead and overall gracile appearance typical of modern Homo sapiens.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): The Liujiang cranium shows the tall forehead and overall gracile appearance typical of modern Homo sapiens.The fossil Liujiang (or Liukiang) hominin has derived traits that classified it as a modern Homo sapiens, though primitive archaic traits were also present. In the skull, which was found nearly complete, the Liujiang hominin had a taller forehead than archaic Homo sapiens but also had an enlarged occipital region (Figure 12.10) (Brown 1999). A reconstruction of the brain based on the endocast of the cranium confirmed these trends along with a larger overall volume (Wu et al. 2008). Other parts of the skeleton also had a mix of modern and archaic traits: for example, the femur fragments suggested a slender length but with thick bone walls (Woo 1959). Dating methods suggested an age of around 67,000 years.

A mandible fragment, teeth, and postcranial skeletal remains of a single adult of indeterminate sex was found by tree farmers in Tianyuan, 50 km from Beijing (Tong 2004). Radiocarbon dating of the bones estimated that they were from 42,000 to 39,000 years ago (Shang et al. 2007). As with other fossils described in this section, researchers noted a few transitional traits between archaic and modern categories, such as deep tooth measurements (the anteroposterior or front-to-back dimension) and a robust tibia. The Tianyuan fossils also had some antemortem tooth loss (which happened during life), osteoarthritis of a left-hand finger joint, and enlargements to muscle attachment sites of the tibia and femur. The evidence pointed to a physically demanding life.

The last Chinese site to describe here is the one that has been studied the longest. In the Zhoukoudian Cave system, where Homo erectus and archaic Homo sapiens have also been found, there were three crania that fit the modern Homo sapiens set of traits (Figure 12.11). These crania were in a part of the cave called the Upper Cave, dating to between 34,000 and 10,000 years ago. The crania were all more globular than that of archaic humans but still lower and longer than later modern humans’ (Brown 1999; Harvati 2009). When compared to one another, the three Upper Cave crania showed significant differences from one another. Comparison of cranial measurements to other populations past and present found no connection with modern East Asians. These findings again show that human variation was very different from what we see today.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): The entrance to the Upper Cave of the Zhoukoudian complex, where crania of three prehistoric modern humans were found.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): The entrance to the Upper Cave of the Zhoukoudian complex, where crania of three prehistoric modern humans were found.Other Asian Modern Humans

Other discoveries in Asia show us where modern Homo sapiens went after the initial expansion. Sites with evidence of modern human occupation stretch from the island of Sri Lanka north to Siberia. The first modern humans may have followed rivers north to settle in colder regions while still accessing the rich freshwater environment.

The Balangoda hominins refer to around 36 modern humans as far back as 38,000 years ago whose fossils were found in numerous cave sites around Sri Lanka (Kennedy et al. 1987). The name also refers to one particularly well-studied skeleton from the archaeological site of Batadombalena. Measurements of Balangoda Man show a closeness to the modern-day Vedda people who live in Sri Lanka, suggesting a direct ancestral relationship. Ornamentation such as pendants and beads, and the presence of shark teeth far from the coast, supported the presence of modern behavior as they were possibly transported for their aesthetic or symbolic value rather than their practical use.

A double-infant burial dated to 28,000 years ago was found in 1928 at the site of Mal’ta in southern Siberia, north of Mongolia (Raghavan et al. 2014). Researchers named the three- to four-year-old individual MA-1. This burial was decorated with Later Stone Age decorations: a beaded necklace, pendants, and a headband. Other accessories and lithics were buried with the pair. Genetic analysis of MA-1 found a connection with both present-day Western Europeans and Native Americans but not East Asians. This finding hints at the complex routes people took in the expansion of the species.

Summary of Modern H. sapiens in the Middle East and Asia

As in Africa, the finds of the Middle East have shown that humans were biologically diverse and had complex relationships with their environment. Work in the Levant showed an initial expansion north from the Sinai Peninsula that did not last. Away from the Levant, expansion continued. People were present in Saudi Arabia, too, as rainfall increased the amount of habitable land. Local resources were used to make lithics and decorative items.

The early Asian presence of modern Homo sapiens was complex and varied as befitting the massive continent. What the evidence shows is that people adapted to a wide array of environments that were far removed from Africa. From the Levant to Sri Lanka, Siberia, and China, humans with modern anatomy used caves that preserved signs of their presence. Faunal and floral remains found in these shelters speak to the flexibility of the human omnivorous diet as local wildlife and foliage became nourishment. Decorative items, often found as burial goods in planned graves, show a flourishing cultural life.

Eventually, modern humans at the southeastern fringe of the geographical range of the species found their way southeast until some became the first humans in Australia.

Crossing to Australia

Expansion of the first modern human Asians, still following the coast, eventually entered an area called Sunda by researchers before continuing on to modern Australia. Sunda was a landmass made up of the modern-day Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. Lowered sea levels connected these places with land bridges, making them easier to traverse. Proceeding past Sunda meant navigating Wallacea, the archipelago that includes the Indonesian islands east of Borneo. The name refers to naturalist Sir Alfred Russel Wallace, who noted that organisms from this region differed from those to the west. Prehistorically, there were many megafauna, large animals that migrating humans would have used for food and materials such as hides and bones. Further southeast was another prehistoric landmass called Sahul, which included New Guinea and Australia as one contiguous continent. This land had never seen hominins or any other primates before modern Homo sapiens arrived. Sites along this path offer clues about how our species handled these changes to the local environment to live successfully as foragers.

While no fossil humans have been found at the Madjedbebe rock shelter in the North Territory of Australia, more than 10,000 artifacts found there show both behavioral modernity and variability (Clarkson et al. 2017). They include a diverse array of stone tools and different shades of ochre for rock art, including mica-based reflective pigment (similar to glitter). The ochre were shaped into what the researchers called “crayons” to be held and used to mark other things. There were also plant and animal remains matching the tools used to process them. One notable find in this category is the partial upper jaw of a thylacine, or Tasmanian wolf, which was colored red. These impressive artifacts date as far back as 56,000 years ago, providing the date for the earliest-known presence of humans in Australia.

The skeletal remains at Lake Mungo are the oldest known in the continent. The lake, now dry, was one of a series located along the southern coast of Australia in New South Wales, far from where the first people entered from the north (Barbetti and Allen 1972; Bowler et al. 1970). Two individuals dating to around 40,000 years ago show signs of artistic and symbolic behavior, including intentional burial. The bones of Lake Mungo 1 (LM1), an adult female, were crushed repeatedly, colored with red ochre, and even cremated (Bowler et al. 1970). Lake Mungo 3 (LM3), a tall older male with a gracile cranium but robust postcranial bones, had his fingers interlocked over his pelvic region (Brown 2000).

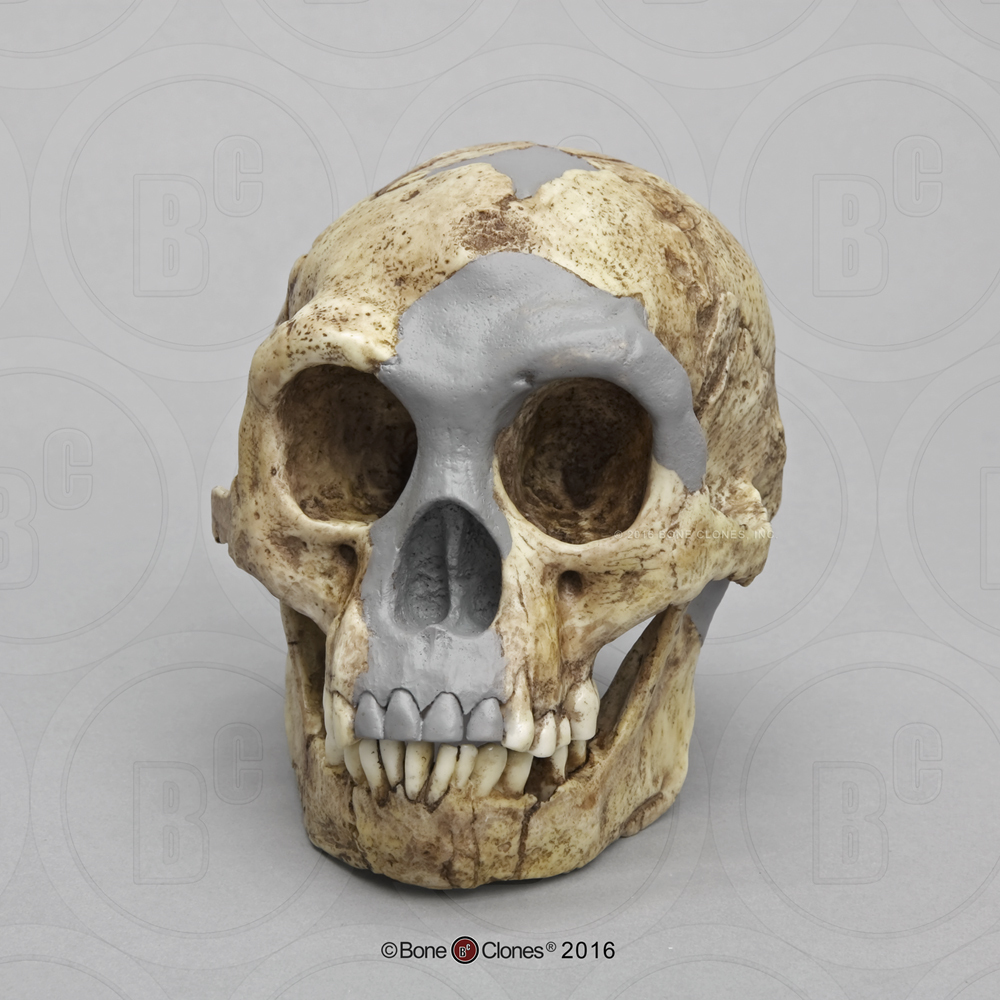

Kow Swamp, also in southern Australia, contained human crania that looked distinctly different from the ones at Lake Mungo (Durband 2014; Thorne and Macumber 1972). The Kow Swamp crania had extremely robust brow ridges and thick bone walls, but these were paired with globular features on the braincase (Figure 12.12). The frontal bones had extremely linear slopes from the brow to the top of the cranium, resembling intentional cranial modification seen in other parts of the world. If the crania were shaped on purpose, they are another sign of symbolic behavior, as the practice has linked to ideas of group cultural identity. By the time of the Kow Swamp people, between 9,000 and 20,000 years ago, cranial modification may have been a meaningful part of culture in southern Australia.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Replica of the Kow Swamp 1 cranium. The shape of the braincase could be due to artificial cranial modification. A competing hypothesis is that it reflects the primitive shape of Homo erectus.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Replica of the Kow Swamp 1 cranium. The shape of the braincase could be due to artificial cranial modification. A competing hypothesis is that it reflects the primitive shape of Homo erectus.Summary of Modern H. sapiens in Australia

The presence of the first humans in Australia along the current northern and southern coasts suggests that they used a route that wrapped around the perimeter of the continent. This path allowed access to both coastal and inland resources. Megafauna was a likely source of food and other resources. The mythology of Australian aborigines today has been linked by researchers to extinct life, such as marsupial tapirs and lions. Predation by humans may be why the megafauna became extinct, leaving the oral tradition of their existence.

The abundant evidence matching the criteria for behavioral modernity shows that the early Australians had a rich artistic and symbolic life. Raw materials must have been transported or traded across long distances in order to make art and color both human and nonhuman skeletal remains. The local varieties of stone tools and art may reflect cultural variation across distant regions of the continent.

The overall view of the first modern humans in Australia from a biological perspective shows a high amount of skeletal diversity. This is similar to the trends seen earlier in Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia. While the Lake Mungo individuals had derived gracile cranial traits, the Kow Swamp crania were measurably more robust.

Northwest to Europe

The first modern human expansion into Europe occurred after other members of our species settled East Asia and Australia. As the evidence from the Levant suggests, modern human movement to Europe may have been hampered by the presence of Neanderthals. Another obstacle was that the colder climate was incompatible with the biology of African modern Homo sapiens, which was adapted for exposure to high heat and ultraviolet radiation. Still, by 40,000 years ago, modern Homo sapiens had enough of a presence in Europe to leave evidence for researchers to find. This time was also the start of the Later Stone Age or Upper Paleolithic, with an expansion in cultural complexity. Connected with the history of science in general, early modern Homo sapiens in Europe have been studied for centuries. Due to the bias in research focus favoring Europe, there is a wealth of evidence to explore. Still, there are also eye-opening discoveries in this area today. This section will cover some of the key evidence of early modern human life in Europe, then go over the typologies used to view the cultural changes in this region.

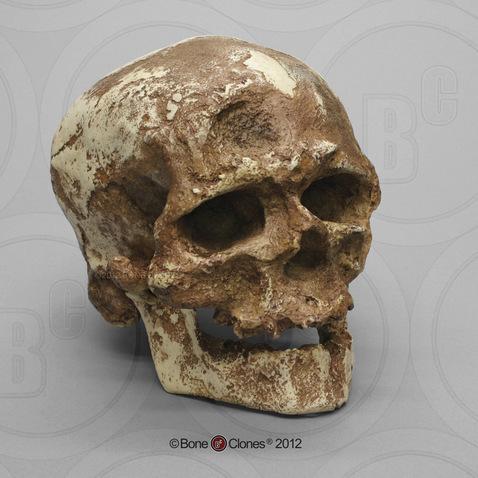

In Romania, the site of Peștera cu Oase (Cave of Bones) had the oldest known remains of modern Homo sapiens in Europe, dated to around 40,000 years ago (Trinkaus et al. 2003a). Among the bones and teeth of cave bears, wolves, ibex, and other animals were the fragmented cranium of one person and the mandible of another (the two bones did not fit each other). Both bones have modern human traits similar to the fossils from the Middle East, but they also had Neanderthal traits. Oase 1, the mandible, has a mental eminence but also extremely large molars (Trinkaus et al. 2003b). This mandible has yielded DNA, opening another dimension of study. Surprisingly, DNA from Oase 1 is equally similar to DNA from present-day Europeans and Asians (Fu et al. 2015). This means that Oase 1 was not the direct ancestor of modern Europeans. The Oase 2 cranium has the derived traits of reduced brow ridges along with archaic wide zygomatic cheekbones (Figure 12.13) (Rougier et al. 2007). What the braincase shows is also between the two extremes: an overall globular shape that had a tall but sloped frontal bone and an occipital bun-like protrusion at the other end. No artifacts were found at this site. The assemblage was likely gathered by either carnivores or geological events such as water action since the Oase human bones were found with a high amount of nonhuman remains.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): This side view of the Oase 2 cranium shows the reduced brow ridges but also occipital bunning that is a sign that modern Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): This side view of the Oase 2 cranium shows the reduced brow ridges but also occipital bunning that is a sign that modern Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals.The term “Cro-Magnon” has entered public usage as a name for any prehistoric modern European Homo sapiens, and maybe any “caveman” of our species, but it technically refers to four adults (three male and one female) and an infant found in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter in France in 1868 (Balzeau et al. 2013). The remains are dated to 28,000 years ago and may all have been intentionally buried along with over 300 pierced seashells and nonhuman skeletal remains.The Cro-Magnon crania are easily identifiable by their rectangular eye orbits, which are more angular than any contemporary (Figure 12.14). Compared to Neanderthal skeletons of the same region, the Cro-Magnons are extremely gracile. The adults also show signs of much pathology, including fused neck vertebrae and healed fractures. The individual Cro-Magnon 1 has skeletal lesions typical of neurofibromatosis type 1, a rare genetic disease that causes tumor growth (Charlier et al. 2018). The combination of disease markers suggest that life for the Cro-Magnons was so physically demanding that it greatly affected the skeleton.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): This reconstruction of the Cro-Magnon 1 skull shows the gracility of modern Homo sapiens along with a disease that marked the bone.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): This reconstruction of the Cro-Magnon 1 skull shows the gracility of modern Homo sapiens along with a disease that marked the bone.Dating to around 26,000 years ago, Předmostí near Přerov in the Czech Republic was a site where people buried over 30 individuals along with many artifacts. Eighteen individuals were found in one mass burial area, a few covered by the scapulae of woolly mammoths (Germonpré, Lázničková-Galetová, and Sablin 2012). While the recovered human skeletons were destroyed in World War II, finely detailed photographic negatives allowed comparisons to other human groups (Figure 12.15). The Předmostí crania were more globular than those of archaic humans but tended to be longer and lower than in later modern humans (Velemínská et al. 2008). The height of the face was in line with modern residents of Central Europe. One standout trait seen on every mandible on this site was an unusually long length to the mandibular body and jutting chin, resulting in a particular local appearance. Besides the human remains, the site contained the bones of over a thousand mammoths. Some of the mammoth remains were shaped by humans, including a limb bone fragment with a carved abstract female figure. There is also skeletal evidence of dog domestication, such as the presence of dog skulls with shorter snouts than in wild wolves (Germonpré, Lázničková-Galetová, and Sablin 2012). In total, Předmostí could have been a settlement dependent on mammoths for subsistence with people participating in artistic behaviors and the artificial selection of early domesticated dogs.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\):This illustration is based upon one of the surviving photographic negatives since the original fossil was lost in World War II. The modern human chin is prominent, as is an archaic occipital bun.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\):This illustration is based upon one of the surviving photographic negatives since the original fossil was lost in World War II. The modern human chin is prominent, as is an archaic occipital bun.Upper Paleolithic European Material Culture

The sequence of modern Homo sapiens technological change in the Later Stone Age has been thoroughly labeled and dated by researchers working in Europe. The style associated with the start of the Upper Paleolithic is the Aurignacian, starting around 40,000 years ago and ending around 27,000 years ago. Items in this tradition include stone blades as well as beads made from shell, bones, and teeth. Next is the Gravettian, which lasted from 6,000 years to 21,000 years ago. This culture is associated with most of the known curvy female figurines, often assumed to be “Venus” figures. Hunting technology also advanced, such as with the first known boomerang, atlatl (spear thrower), and archery. The Solutrean, marked by further innovation in delicate tool work, is the following style from 21,000 to 17,000 years ago. After that time, the Magdalenian tradition spread. This culture further expanded on fine bone tool work, including barbed spearheads and fishhooks (Figure 12.16). The end of the Magdalenian is also the end of the Later Stone Age and the Pleistocene Period. While these labels and time spans apply to Europe, other regions also showed changes in material culture to some of the same types of technology. Uncovering the regional timelines of cultural styles around the world to see these transitions on a global scale is an ongoing goal of paleoanthropologists.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\): This drawing from 1891 shows an array of Magdalenian-style barbed points found in the burial of a reindeer hunter. They were carved from antler.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\): This drawing from 1891 shows an array of Magdalenian-style barbed points found in the burial of a reindeer hunter. They were carved from antler.Among the many European sites dating to the Later Stone Age, the famous cave art sites deserve mention. Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in southern France dates to separate Aurignacian occupations 31,000 years ago and 26,000 years ago. Over a hundred art pieces representing 13 animal species are preserved. Some depicted species are common to European cave art, such as deer and horses. Others are rare, such as rhinos and owls. Two possible human figures are in the deepest gallery of the cave system. Besides the painted figures, the tracks and skulls of cave bears and an ibex were also found in the cave. Another famous French cave with art is Lascaux, which is several thousand years younger at 17,000 years ago in the Magdalenian period. At this site, there are over 6,000 painted figures on the walls and ceiling (Figure 12.17). The paint was made of a mix of mineral pigments in liquid binder made from fat or clay. Scaffolding and lighting must have been used to make the paintings on the walls and ceiling deep in the cave. Overall, visiting Lascaux as a contemporary must have been an awesome experience: trekking deeper in the cave lit only by torches giving glimpses of animals all around as mysterious sounds echoed through the galleries. The professionally lit photographs of today do not give the original context justice, though replicas have been built to simulate the experience for tourists. Both Chauvet and Lascaux have been closed to all but researchers due to the degradation of the art when tourism was allowed.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Photograph of just one surface with cave art at Lascaux Cave. The most prominent piece here is the Second Bull, found in a chamber called the Hall of Bulls. Smaller cattle and horses are also visible.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Photograph of just one surface with cave art at Lascaux Cave. The most prominent piece here is the Second Bull, found in a chamber called the Hall of Bulls. Smaller cattle and horses are also visible.Summary of Modern H. sapiens in Europe

Study of Europe in the Upper Paleolithic gives a more detailed view of the general pattern of biological and cultural change linked with the arrival of modern Homo sapiens. The modern humans experienced a rapidly changing culture that from our perspective went through four major growths in complexity and refinement. Skeletally, the increasing globularity of the cranium and the gracility of the rest of the skeleton continued, though with unique regional traits, too. The cave art sites showed a deeper use of expression and symbolism, though the exact meaning is unclear. With survival dependent on the surrounding ecology, painting the figures may have connected people to important and impressive wildlife at both a physical and spiritual level. Both reverence for animals and the use of caves for an enhanced sensory experience are common to cultures today and through recorded history.

In the next section we continue our exploration of Homo sapiens origins by seeing the genetic evidence of interbreeding between the archaic and modern types, leaving just the latter to continue to the present day.