13.1.5: Physical Changes of Aging

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 63356

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA) (NIA, 2011b) began in 1958 and has traced the aging process in 1,400 people from age 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA have found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another. However, some key generalization can be made including heart muscles thickening with age, arteries becoming less flexible, and lung capacity diminishing. Kidneys become less efficient in removing waste from the blood, and the bladder loses its ability to store urine. Brain cells also lose some functioning, but new neurons can also be produced. Many of these changes are determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease. Other changes in late adulthood include:

Body Changes: Everyone’s body shape changes naturally as they age. According to the National Library of Medicine (2014) after age 30 people tend to lose lean tissue, and some of the cells of the muscles, liver, kidney, and other organs are lost. Tissue loss reduces the amount of water in your body and bones may lose some of their minerals and become less dense (a condition called osteopenia in the early stages and osteoporosis in the later stages). The amount of body fat goes up steadily after age 30, and older individuals may have almost one third more fat compared to when they were younger. Fat tissue builds up toward the center of the body, including around the internal organs.

Skin and Hair: With age skin becomes thinner, less elastic, loses fat, and no longer looks plump and smooth. Veins and bones can be seen more easily and scratches, cuts, and bumps can take longer to heal. Years exposed to the sun may lead to wrinkles, dryness, age spots, and cancer. Older people may bruise more easily, and it can take longer for these bruises to heal. Some medicines or illnesses may also cause bruising. Gravity can cause skin to sag and wrinkle, and smoking can wrinkle the skin. Also, seen in older adults are age spots, previously called “liver spots”. They look like flat, brown spots and are often caused by years in the sun. Skin tags are small, usually flesh-colored growths of skin that have a raised surface. They become common as people age, especially for women, but both age spots and skin tags are harmless (NIA, 2015f).

Nearly everyone has hair loss as they age, and the rate of hair growth slows down as many hair follicles stop producing new hairs. The loss of pigment and subsequent graying begun in middle adulthood continues in late adulthood.

Sarcopenia is the loss of muscle tissue as a natural part of aging. Sarcopenia is most noticeable in men, and physically inactive people can lose as much as 3% to 5% of their muscle mass each decade after age 30, but even when active muscle loss still occurs (Webmd, 2016). Symptoms include a loss of stamina and weakness, which can decrease physical activity and subsequently further shrink muscles. Sarcopenia typically happens faster around age 75, but it may also speed up as early as 65 or as late as 80. Factors involved in sarcopenia include a reduction in nerve cells responsible for sending signals to the muscles from the brain to begin moving, a decrease in the ability to turn protein into energy, and not receiving enough calories or protein to sustain adequate muscle mass. Any loss of muscle is important because it lessens strength and mobility, and sarcopenia is a factor in frailty and the likelihood of falls and fractures in older adults. Maintaining strong leg and heart muscles are important for independence. Weight-lifting, walking, swimming, or engaging in other cardiovascular exercises can help strengthen the muscles and prevent atrophy.

Height and Weight: The tendency to become shorter as one ages occurs among all races and both sexes. Height loss is related to aging changes in the bones, muscles, and joints. People typically lose almost one-half inch every 10 years after age 40, and height loss is even more rapid after age 70. A total of 1 to 3 inches in height is lost with aging. Changes in body weight vary for men and woman. Men often gain weight until about age 55, and then begin to lose weight later in life, possibly related to a drop in the male sex hormone testosterone. Women usually gain weight until age 65, and then begin to lose weight. Weight loss later in life occurs partly because fat replaces lean muscle tissue, and fat weighs less than muscle. Diet and exercise are important factors in weight changes in late adulthood (National Library of Medicine, 2014).

Sensory Changes in Late Adulthood

Vision: In late adulthood, all the senses show signs of decline, especially among the oldest-old. In the last chapter, you read about the visual changes that were beginning in middle adulthood, such as presbyopia, dry eyes, and problems seeing in dimmer light. By later adulthood these changes are much more common. Three serious eyes diseases are more common in older adults: Cataracts, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Only the first can be effectively cured in most people.

Cataracts are a clouding of the lens of the eye. The lens of the eye is made up of mostly water and protein. The protein is precisely arranged to keep the lens clear, but with age some of the protein starts to clump. As more of the protein clumps together the clarity of the lens is reduced. While some adults in middle adulthood may show signs of cloudiness in the lens, the area affected is usually small enough to not interfere with vision. More people have problems with cataracts after age 60 (NIH, 2014b) and by age 75, 70% of adults will have problems with cataracts (Boyd, 2014). Cataracts also cause a discoloration of the lens, tinting it more yellow and then brown, which can interfere with the ability to distinguish colors such as black, brown, dark blue, or dark purple.

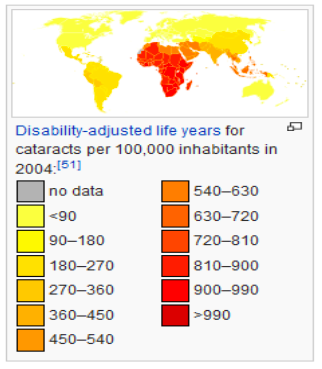

Risk factors besides age include certain health problems such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity, behavioral factors such as smoking, other environmental factors such as prolonged exposure to ultraviolet sunlight, previous trauma to the eye, long-term use of steroid medication, and a family history of cataracts (NEI, 2016a; Boyd, 2014). Cataracts are treated by removing and replacing the lens of the eye with a synthetic lens. In developed countries, such as the United States, cataracts can be easily treated with surgery. However, in developing countries, access to such operations are limited, making cataracts the leading cause of blindness in late adulthood in Third World nations (Resnikoff, Pascolini, Mariotti & Pokharel, 2004). As shown in Figure 9.15, areas of the world with limited medical treatment for cataracts often results in people living more years with a serious disability. For example, of those living in the darkest red color on the map, more than 990 out of 100,00 people have a shortened lifespan due to the disability caused by cataracts.

Older adults are also more likely to develop age-related macular degeneration, which is the loss of clarity in the center field of vision, due to the deterioration of the macula, the center of the retina. Macular degeneration does not usually cause total vision loss, but the loss of the central field of vision can greatly impair day-to-day functioning. There are two types of macular degeneration: dry and wet. The dry type is the most common form and occurs when tiny pieces of a fatty protein called drusen form beneath the retina. Eventually the macular becomes thinner and stops working properly (Boyd, 2016). About 10% of people with macular degeneration have the wet type, which causes more damage to their central field of vision than the dry form. This form is caused by an abnormal development of blood vessels beneath the retina. These vessels may leak fluid or blood causing more rapid loss of vision than the dry form.

The risk factors for macular degeneration include smoking, which doubles your risk (NIH, 2015a); race, as it is more common among Caucasians than African Americans or Hispanics/Latinos; high cholesterol; and a family history of macular degeneration (Boyd, 2016). At least 20 different genes have been related to this eye disease, but there is no simple genetic test to determine your risk, despite claims by some genetic testing companies (NIH, 2015a). At present, there is no effective treatment for the dry type of macular degeneration. Some research suggests that certain patients may benefit from a cocktail of certain antioxidant vitamins and minerals, but the results are mixed at best. They are not a cure for the disease nor will they restore the vision that has been lost. This “cocktail” can slow the progression of visual loss in some people (Boyd, 2016; NIH, 2015a). For the wet type medications that slow the growth of abnormal blood vessels, and surgery, such as laser treatment to destroy the abnormal blood vessels may be used. Only 25% of those with the wet version may see improvement with these procedures (Boyd, 2016).

A third vision problem that increases with age is glaucoma, which is the loss of peripheral vision, frequently due to a buildup of fluid in eye that damages the optic nerve. As you age the pressure in the eye may increase causing damage to the optic nerve. The exterior of the optic nerve receives input from retinal cells on the periphery, and as glaucoma progresses more and more of the peripheral visual field deteriorates toward the central field of vision. In the advanced stages of glaucoma, a person can lose their sight. Fortunately, glaucoma tends to progresses slowly (NEI, 2016b).

Glaucoma is the most common cause of blindness in the U.S. (NEI, 2016b). African Americans over age 40, and everyone else over age 60 has a higher risk for glaucoma. Those with diabetes, and with a family history of glaucoma also have a higher risk (Owsley et al., 2015). There is no cure for glaucoma, but its rate of progression can be slowed, especially with early diagnosis. Routine eye exams to measure eye pressure and examination of the optic nerve can detect both the risk and presence of glaucoma (NEI, 2016b). Those with elevated eye pressure are given medicated eye drops. Reducing eye pressure lowers the risk of developing glaucoma or slow its progression in those who already have it.

Hearing: As you read in Chapter 8, our hearing declines both in terms of the frequencies of sound we can detect and the intensity of sound needed to hear as we age. These changes continue in late adulthood. Almost 1 in 4 adults aged 65 to 74 and 1 in 2 aged 75 and older have disabling hearing loss (NIH, 2016). Table 9.4 lists some common signs of hearing loss.

| Have trouble hearing over the telephone |

| Find it hard to follow conversations when two or more people are talking |

| Often ask people to repeat what they are saying |

| Need to turn up the TV volume so loud that others complain |

| Have a problem hearing because of background noise |

| Think that others seem to mumble |

| Can't understand when women and children speak to you |

Adapted from NIA, 2015c

Presbycusis is a common form of hearing loss in late adulthood that results in a gradual loss of hearing. It runs in families and affects hearing in both ears (NIA, 2015c). Older adults may also notice tinnitus, a ringing, hissing, or roaring sound in the ears. The exact cause of tinnitus is unknown, although it can be related to hypertension and allergies. It may come and go or persist and get worse over time (NIA, 2015c). The incidence of both presbycusis and tinnitus increase with age and males have higher rates of both around the world (McCormak, Edmondson-Jones, Somerset, & Hall, 2016).

Your auditory system has two jobs: To help you to hear, and to help you maintain balance. Your balance is controlled by the brain receiving information from the shifting of hair cells in the inner ear about the position and orientation of the body. With age this function of the inner ear declines which can lead to problems with balance when sitting, standing, or moving (Martin, 2014).

Taste and Smell: Our sense of taste and smell are part of our chemical sensing system. Our sense of taste, or gustation, appears to age well. Normal taste occurs when molecules that are released by chewing food stimulate taste buds along the tongue, the roof of the mouth, and in the lining of the throat. These cells send messages to the brain, where specific tastes are identified. After age 50 we start to lose some of these sensory cells. Most people do not notice any changes in taste until ones 60s (NIH: Senior Health, 2016b). Given that the loss of taste buds is very gradual, even in late adulthood, many people are often surprised that their loss of taste is most likely the result of a loss of smell.

| Presbyomia | Smell loss due to aging |

| Hyposmia | Loss of only certain odors |

| Anosmia | Total loss of smell |

| Dysomia | Change in the perception of odors. Familiar odors are distorted. |

| Phantosmia | Smell odors that are not present |

Adapted from NIH Senior Health: Problems with Smell

Our sense of smell, or olfaction, decreases more with age, and problems with the sense of smell are more common in men than in women. Almost 1 in 4 males in their 60s have a disorder with the sense of smell, while only 1 in 10 women do (NIH: Senior Health, 2016b). This loss of smell due to aging is called presbyosmia. Olfactory cells are located in a small area high in the nasal cavity. These cells are stimulated by two pathways; when we inhale through the nose, or via the connection between the nose and the throat when we chew and digest food. It is a problem with this second pathway that explains why some foods such as chocolate or coffee seem tasteless when we have a head cold. There are several types of loss of smell. Total loss of smell, or anosmia, is extremely rare.

Problems with our chemical senses can be linked to other serious medical conditions such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or multiple sclerosis (NIH: Senior Health, 2016a). Any sudden change should be checked out. Loss of smell can change a person’s diet, with either a loss of enjoyment of food and eating too little for balanced nutrition, or adding sugar and salt to foods that are becoming blander to the palette.

Touch: Research has found that with age, people may experience reduced or changed sensations of vibration, cold, heat, pressure, or pain (Martin, 2014). Many of these changes are also aligned with a number of medical conditions that are more common among the elderly, such as diabetes. However, there are changes in the touch sensations among healthy older adults. The ability to detect changes in pressure have been shown to decline with age, with it being more pronounced by the 6th decade and diminishing further with advanced age (Bowden & McNelty, 2013). Yet, there is considerable variability, with almost 40% showing sensitivity that is comparable to younger adults (Thornbury & Mistretta, 1981). However, the ability to detect the roughness/smoothness or hardness/softness of an object shows no appreciable change with age (Bowden & McNulty, 2013). Those who show increasing insensitivity to pressure, temperature, or pain are at risk for injury (Martin, 2014).

Pain: According to Molton and Terrill (2014), approximately 60%-75% of people over the age of 65 report at least some chronic pain, and this rate is even higher for those individuals living in nursing homes. Although the presence of pain increases with age, older adults are less sensitive to pain than younger adults (Harkins, Price, & Martinelli, 1986).

Farrell (2012) looked at research studies that included neuroimaging techniques involving older people who were healthy and those who experienced a painful disorder. Results indicated that there were age-related decreases in brain volume in those structures involved in pain. Especially noteworthy were changes in the prefrontal cortex, brainstem, and hippocampus. Women are more likely to identify feeling pain than men (Tsang et al., 2008). Women have fewer opioid receptors in the brain, and women also receive less relief from opiate drugs (Garrett, 2015). Because pain serves an important indicator that there is something wrong, a decreased sensitivity to pain in older adults is a concern because it can conceal illnesses or injuries requiring medical attention.