9.3: Intersectionality

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 104083

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Women and Gender Issues

Where Do Women Fit In?

Asian America has masked a series of internal tensions. In order to produce a sense of racial solidarity, Asian American activists framed social injustices in terms of race, veiling other competing social categories such as gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and nationality. The relative absence of gender as a lens for Asian American activism and resistance throughout the 1970s until the present should therefore be read as neither an indication of the absence of gender inequality nor of the disengagement of Asian American women from issues of social justice.

Many Asian American activists (including some of the authors in this book) refute the label "feminist" although their work pays special attention to the experiences of women. Sometimes this feeling reflects a fear of alienating men -- a consequence that seems inevitable if men are unable to own up to their gender privilege. At other times, the antipathy towards feminism reflects the cultural insensitivity and racism of white, European feminists.

Dragon Ladies: A Brief History

Empress Tsu-his ruled China from 1898 to 1908 from the Dragon Throne. The New York Times described her as "the wicked witch of the East, a reptilian dragon lady who had arranged the poisoning, strangling, beheading, or forced suicide of anyone who had ever challenged her autocratic rule." The shadow of the Dragon Lady -- with her cruel, perverse, and inhuman ways -- continued to darken encounters between Asian women and the West they flocked to for refuge.

Far from being predatory, many of the first Asian women to come to the U.S. in the mid-1800s were disadvantaged Chinese women, who were tricked, kidnapped, or smuggled into the country to serve the predominantly male Chinese community as prostitutes. The impression that all Asian women were prostitutes, born at that time, "colored the public perception of, attitude toward, and action against all Chinese women for almost a century," writes historian Sucheng Chan.

Police and legislators singled out Chinese women for special restrictions "not so much because they were prostitutes as such (since there were also many white prostitutes around) but because -- as Chinese -- they allegedly brought in especially virulent strains of venereal diseases, introduced opium addiction, and enticed white boys into a life of sin," Chan also writes. Chinese women who were not prostitutes ended up bearing the brunt of the Chinese exclusion laws that passed in the late 1800s.

During these years, Japanese immigration stepped up, and with it, a reactionary anti-Japanese movement joined established anti-Chinese sentiment. During the early 1900s, Japanese numbered less than 3 percent of the total population in California, but nevertheless encountered virulent and sometimes violent racism. The "picture brides" from Japan who emigrated to join their husbands in the U.S. were, to racist Californians, "another example of Oriental treachery," according to historian Roger Daniels.

It bears noting that despite the fact that they weren't in the country in large numbers, Asian women shouldered much of the cost of subsidizing Asian men's labor. U.S. employers didn't have to pay Asian men as much as other laborers who had families to support, since Asian women in Asian bore the costs of rearing children and taking care of the older generation.

Asian women who did emigrate here before the 1960s were also usually employed as cheap labor. In the pre-World War II years, close to half of all Japanese American women were employed as servants or laundresses in the San Francisco area. The World War II internment of Japanese Americans made them especially easy to exploit: they had lost their homes, possessions, and savings when forcibly interned at the camps, Yet, in order to leave, they had to prove they had jobs and homes. U.S. government officials thoughtfully arranged for their employment by fielding requests, most of which were for servants.

Immigration Characteristics

Issues concerning immigration affect many aspects of the Asian American community. This is understandable since almost two-thirds of all Asian Americans are foreign-born. Before trying to examine the many controversies regarding the benefits or costs of immigration, we first need to examine the characteristics of the immigrant population, Asian and otherwise.

The Immigrant and U.S. Born Populations

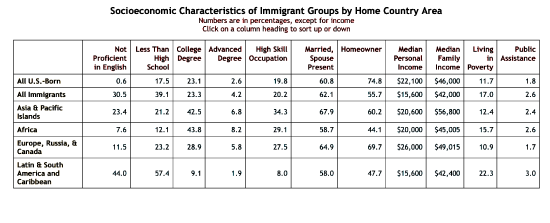

The data in the following table was calculated using the 2000 Census 1% Public Use Microdata Samples, and they compare different immigrant groups (based on their home country area) with each other and with all those who are either U.S.-born or foreign-born in the U.S. on different measures of socioeconomic achievement. You can click on a column heading to sort up or down. You can also read the detailed description of the methodology and terminology used to create the statistics.

The statistics include immigrants from all countries, not just those from Asia. According to the 2000 Census, the immigrant/foreign-born population of the U.S. was just about 28,910,800. Of these, 5.5% were Black, 25.9% were Asian, 46.4% were Hispanic/Latino, and 22.1% were white. The statistics below represent sound research but different statisticis can be used to support both sides of an issue. So you can choose to agree with my conclusions or not.

We should first understand that immigrating to another country is not an easy thing to do. It almost always involves making elaborate preparations and costs a lot of money. Many times it also means giving up personal relationships at home (at least temporarily, if not permanently) and learning a new language and culture. The point is, not everyone who wants to immigrate actually does. In fact, those who are very poor rarely immigrate -- they just don't have the resources. Those who do immigrate tend to be from their country's middle and professional classes.

This point is illustrated by the results from the table, which compares various socioeconomic characteristics between U.S.-born and immigrant groups by their home country area. To view the full-size table of statistics, click on Table 9.3.2. Once the table appears, you can click on a column heading to sort up or down. You can also read the detailed description of the methodology and terminology used to create the statistics.

The results show that immigrants as a group actually have a slightly higher college degree attainment rate and a much higher rate of having an advanced degree (medical, law, or doctorate) than do the U.S.-born. On both measures, immigrants from Africa actually have the highest educational achievement rates and they also have the lowest rate of having less than a high school education. African immigrants are also most likely to be in the labor market.

Therefore, it's clear that immigrants from Africa tend to come from their country's elite classes. In contrast, the statistics point out that immigrants from Latin and South America and from the Caribbean have the lowest educational attainment rates. We can probably surmise from this that they are more likely to be from rural or working class backgrounds. As another example of this implication, immigrants from Latin/South America and the Caribbean have the lowest median personal (per capita) income, as well as the highest rates of living in poverty and receiving public assistance.

In addition, they have the lowest rates of being married with spouse present, working in a high skill (executive, professional, technical, or upper management) occupation and the lowest media socioeconomic index (SEI) score, a measure of occupational prestige. However, these statistics do not necessarily lead to the conclusion that immigrants from Latin/South America and the Caribbean are a drain on the U.S. economy or that they consume more benefits than they contribute. For a discussion of that issue, be sure to read the article on the impacts of immigration.

Other Groups and Their Levels of Success

In regard to other immigrant groups, the statistics above show that immigrants from Asia and Pacific Islands compare quite favorably to other immigrants and to the U.S.-born as well. However, there also seems to be a much wider spread of characteristics among Asian immigrants. In other words, there seems to be many who are more likely to be from rural or working class backgrounds (and therefore have lower socioeconomic attainment rates), along with many other Asian immigrants from middle class and professional backgrounds who have very high attainment rates.

For example, Asian and Pacific Islander immigrants have a much rate of not being proficient in English than do the U.S.-born (which is understandable since English is a foreign language to most Asians) and they also have a higher rate of less than high school completion than do the U.S.-born. On the other hand, Asian & Pacific Islander immigrants have a median personal (per capita) income comparable to the U.S.-born, along with a much higher median family income. They also have higher rates of having a college degree, an advanced degree, and working at a high skill occupation than do the U.S.-born.

Similarly, immigrants from Europe, Russia, and Canada tend to have socioeconomic attainment levels that are very comparable to that for the U.S.-born and in several categories, outperform them as well. These include higher rates of having a college degree, an advanced degree, working in a high skill occupation, and most notably, the highest median personal (per capita) income of all groups in the table. Interestingly, they also have the lowest rate of being in the labor market, which may suggest that many are retired but rather affluent as well.

Overall, all of these socioeconomic measures and statistics comparing immigrants to the U.S.-born population suggest that in most cases, both groups are relatively close to the other. But again, these numbers can be used to support both sides of the immigration debate -- that immigrants are not achieving as well as the U.S.-born and vice-versa. However, it does seem clear that these statistics do not support the stereotype of immigrants as being chronically unemployed, in poverty, and on public assistance. They do suggest that just like any other social group in the U.S., there is a lot of diversity within each group and that we as a society should be careful about making sweeping generalizations about all members of a particular group.

Religion, Spirituality & Faith

Among the more traditional elements of Asian American culture, religion, spirituality, and faith have always been important to Asian American communities, as they were for many generations before them. But within the diversity of the Asian American community, so too comes diversity in our religious beliefs and practices.

Which Religion is the Most Popular?

One of the first questions to examine is, which religions or faith traditions are the most popular among Asian Americans and among each of the different Asian ethnic groups? Unfortunately, nationally representative and reliable statistics are difficult to find. There are few studies or data that would answer these questions conclusively, particularly ones that break down religious affiliation among different Asian ethnic groups.

|

American Religious Identfication Survey 1990-2008: Asian Americans |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2001 | 2008 | |||

| None/Agnostic | 16% | 22% | 27% | ||

| Eastern Religions | 8% | 22% | 21% | ||

| Catholic | 27% | 20% | 17% | ||

| Other Christian | |||||

| 13% | 11% | 10% | |||

| 11% | 6% | 6% | |||

| 9% | 4% | 3% | |||

| 3% | 2% | 2% | |||

|

Mormon |

2% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Muslim | 3% | 8% | 8% | ||

| New Religious Movements | 2% | 1% | 2% | ||

| Jewish | 1% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Don't Know/ Declined to Answer | 4% | 5% | 5% | ||

Nonetheless, there are some statistics that give a general picture of religious affiliation within the Asian American community. One of the largest, most up to date, and most comprehensive sources is the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), conducted by researchers at Trinity College (CT). The ARIS was first conducted in 1990, again in 2000, and the most recent wave was completed in 2008. The 2008 study includes data from a large, nationally representative sample of 54,461 U.S. adults in the 48 contiguous states.

The following Table 9.3.5 is taken from the ARIS 2008 report. The results show that while no religion can claim a majority of followers in the Asian American community, as of 2008, those who claim no religious affiliation are the largest group. In fact, this group has grown significantly since the first ARIS study in 1990 and its percentage in 2008 (27%) among Asian American is the largest of all the major racial ethnic groups in the study (whites are second with 16% claiming no religious affiliation). The second-largest religious group among Asian Americans are "Eastern Religions" that include Buddhist, Hindu, Taoist, Baha'i, Shintoist, Zoroastrian, and Sikh. These Eastern Religions saw a dramatic increase from 1990 to 2001, then leveled off in 2008. Catholics are the third-largest group at 17% in 2008, with their proportions declining notably from 27% in 1990.

| 2008 | |||

| Christian | 45% | ||

| Protestant | 27% | ||

| Evangelical | 17% | ||

| Mainline | 9% | ||

| Historically Black | < 0.5% | ||

| Catholic | 17% | ||

| Mormon | 1% | ||

| Jehovah's Witness | < 0.5% | ||

| Orthodox | < 0.5% | ||

| Other Christian | < 0.5% | ||

| Eastern & Other Religions | 30% | ||

| Hindu | 14% | ||

| Buddhist | 9% | ||

| Muslim | 4% | ||

| Other World Religions | 2% | ||

| Other Faiths | 1% | ||

| Jewish | < 0.5% | ||

| Unaffiliated | 23% | ||

| Secular Unaffiliated | 11% | ||

| Religious Unaffiliated | 5% | ||

| Agnostic | 4% | ||

| Atheist | 3% | ||

| Don't Know/Refused | 2% | ||

The category of "Christian Generic" (comprising those who identified as Christian, Protestant, Evangelical/ Born Again Christian, Born Again, Fundamentalist, Independent Christian, Missionary Alliance Church, and Non-Denominational Christian) is the fourth-largest group at 10% in 2008. Other Christian and Protestant denominations are listed below that. The results show that in 2008, Muslims represented 8% of the Asian American population (up from 3% in 1990) and "New Religious Movements" (comprising those who identified as Scientology, New Age, Eckankar, Spiritualist, Unitarian-Universalist, Deist, Wiccan, Pagan, Druid, Indian Religion, Santeria, and Rastafarian) claiming 2% in 2008.

These results are largely confirmed by a second comprehensive survey of religious identification taken in 2008, the U.S. Religious Landscape Survey (1.2 MB), a national survey of over 35,000 respondents conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.

In contrast to the ARIS 2008 report, the USLRS methodology sometimes includes the same denomination with separate categories (i.e., Baptists can be both "Evangelical" and "Mainline") -- please check page 12 and Appendix 2 of the USLRS report for the exact categorizations and their detailed explanation of their methodology. The data shown here is for Asian American respondents only and is taken from page 40 of their report.

Again the data show that Christian faiths and denominations claim the highest percentage of followers among Asian Americans, with Eastern Religions and unaffiliated responses also claiming large numbers of respondents. Interesting, once the unique faiths within the "Eastern Religions" category are expanded, we see that Hinduism is the mos popular eastern faith among Asian Americans (due largely to the large size of the Indian American population), with Buddhism second.

Unfortunately, neither the ARIS nor the USLRS studies break the religious affiliation down to specific Asian ethnic groups. For that matter, I have yet to find any research that does. So to try to measure the size of religions within each ethnic group, we can look at the proportions for different religions within that Asian country. Although it's not completely accurate, it's a generally safe assumption that the religious proportions within an Asian country are similar to that within its community in the U.S., since the majority of Asian Americans are foreign-born, as stated in the 2000 CIA World Factbook:

- Bangladesh: Muslim 88.3%, Hindu 10.5%, other 1.2%

- India: Hindu 80%, Muslim 14%, Christian 2.4%, Sikh 2%, Buddhist 0.7%, Jains 0.5%, other 0.4%

- Philippines: Roman Catholic 83%, Protestant 9%, Muslim 5%, Buddhist and other 3%

- Japan: observe both Shinto and Buddhist 84%, other 16% (including Christian 0.7%)

- South Korea: Christian 49%, Buddhist 47%, Confucianist 3%, Shamanist, Chondogyo (Religion of the Heavenly Way), and other 1%

Again, these stats are imperfect because as China and Viet Nam are both officially atheist countries, there are no statistics on the proportions of religions in each country.

How Religion, Spirituality, and Faith Help

Ultimately, as there is so much diversity in the Asian American population in so many ways, so too this applies to our religions and practices of spirituality and faith. But they all share the commonality of helping Asian Americans adjust to life in the U.S. and all the issues that surround what it means to be an Asian American.

As several social scientists point out, these various forms of spirituality and faith help Asian Americans to deal with the upheavals of immigration, adapting to a new country, and other difficult personal and social transformations by providing a safe and comfortable environment in which immigrants can socialize, share information, and assist each other. In this process, religious traditions can help in the process of forming Asian immigrant communities by giving specific Asian ethnic groups another source of solidarity, in addition to their common ethnicity, on which to build relationships and cooperation. In fact, history shows that numerous churches and religious organizations played very important roles in helping immigrants from China, Japan, the Philippines, South Asia, and Korea adjust to life in the U.S.

Also, the secular functions of religion are just as, if not even more important in helping Asian Americans in their everyday lives. Specifically, many churches, temples, and other religious organizations provide their members with important and useful services around practical, everyday matters such as translation assistance. Other practical examples include information and assistance on issues relating to education, employment, housing, health care, business and financial advice, legal advice, marriage counseling, and dealing with their Americanized children, etc. As such, many churches are almost like social service agencies in terms of the ways in which they help Asian Americans in practical, day-to-day matters.

Other scholars and studies show that churches can also provide social status and prestige for their members. As one example sociologist Pyong Gap Min describes that since many Korean immigrants face underemployment due to their lack of English fluency once they immigrate to the U.S. (especially if they come from educated and professional backgrounds in Korea), they often feel ashamed, embarrassed, or alienated as they adjust to their lower status level in the U.S. Within their church however, many Korean immigrants find a sense of status through official positions inside the church. These can include being assistant ministers, education directors, unordained associate pastors, elders, deacons, and committee chairs, etc.

Finally, as Bankston and Zhou point out in their study of the New Orleans Vietnamese community, religion can play a significant part in affecting a young Asian American's ethnic identity. The Catholic churches in the Vietnamese section of the city helped to keep young Vietnamese Americans integrated within the larger community. Those youngsters who attended church and participated in religious activities more were more likely to do well in school and to stay out of trouble.

Of course, religion, spirituality, and faith is only one part of this adaptation and socialization process and it interacts with many other factors in affecting how an Asian immigrant adjusts to his/her new life in the U.S. Nonetheless, its power is undeniable. For hundreds of generations in the past, it has bonded communities and been the basis for many people's lives. Even with changes in culture, physical location, and social institutions, its effect lives on.

Young, Gay, and APA

Asian Americans who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) frequently face a double or even triple jeopardy -- being targets of prejudice and discrimination because of their ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. The following is an article entitled "Young, Gay, and APA," originally published in the July 17, 1999 issue of AsianWeek Magazine, written by Joyce Nishioka. It captures many of the obstacles and challenges that LGBT Asian Americans go through as they search for acceptance and happiness with the multiple forms of their personal identities.

Double Jeopardy

Nineteen-year-old Eric Aquino remembers a day not that long ago when he kneeled down to tie his shoe during P.E. class. He looked up to find a boy towering over him, saying, "That's where you belong" and making a comment about oral sex. "People teased me because they perceived me as a gay, fag queer," he remembers. "What could I do but ignore it? One thing I always did was ignore it."

While feelings of rejection and questions about "being normal" haunt most adolescents, they often hit harder at those who are minorities, either racial or sexual. And too often, those are the kids who get the least support. A 1989 study from the Department of Health and Human Services found that a gay teen who comes out to his or her parents faced about a 50-50 chance of being rejected and 1 in 4 had to leave home. Ten years later, a study in The Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine found that gay and bisexual teens are more than three times as likely to attempt suicide as other youths.

Surveys indicate that 80 percent of gay students do not feel safe in schools, and one poll by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed 1 in 13 high school students had been attacked or harassed because they were perceived to be homosexual. Nationwide, 18 percent of all gay students are physically injured to the point they require medical treatment, and they are seven times as likely as their straight peers to be threatened with a weapon at school, according to the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network.

Protecting homosexual Asian teens from discrimination requires double-duty measures, advocates say. Ofie Virtucio, a coordinator for AQUA, San Francisco's only citywide organization for gay Asian American teenagers (now known as the API Wellness Center), maintains that they are especially likely to be closeted and ignored. "Asians are the model minorities," she says, describing a common stereotype. "They can't be gay or at risk; they don't commit suicide or self-mutilate." In reality, Kim says, "There are many API youths in the California public school system who are gay or perceived as being gay and face angry discrimination and harassment. And there is nothing to adequately protect them."

As Kwok and thousands of others might attest, to be young, gay and APA is to simultaneously confront the ugly specters of barriers and discrimination that come with being gay in America and those that come with being Asian in America. "With the anti-Asian sentiment, students are harassed more for being Asian because it's more visible than sexuality." says San Francisco school district counselor Crystal Jang.

The Closet is a Lonely Place to Live

"People don't think there are API gays and lesbians," Virtucio says. "There is hardly any research, and no money goes to them." Consequently, no one knows precisely how many of San Francisco's Asian American children are gay. But if the often quoted figure of 10 percent of a population holds, the figure could exceed 1,300 in the public junior high and high schools alone. Asian American students, says Jang, account for about 90 percent of the kids she sees through the district's Support Services for Sexual Minorities Youth Program. Though there are more support groups for gay youths than ever before, Virtucio said many Asian American teens find it difficult to fit in. Nor do they have any role models. This decade's most noted gays and lesbians -- actresses Ellen DeGeneres and Anne Heche, Ambassador James Hormel and former Wisconsin congressman Steve Gunderson, Migden and Kuehl -- are all white, and so is society's perception of gay America.

"They can't go to programs for queer gay youths when no one speaks their language," Virtucio says. "How can they be understood when they talk about their close-knit family they can never come out to? They need to see people like them. Even if it's just serving rice, they need something familiar so they could [relate] and feel like they could be part of this community," says Virtucio, who touts her four-year-old group as "a channel to come out." In the summer, 20 to 30 teens -- half of whom are immigrants -- go to AQUA's weekly drop-in sessions. Though the group initially attracted mostly college-age men, most of its members today are younger, and half are female. At a recent get-together, the girls seemed much less vocal than boys, and though several young men agreed to be interviewed, no girls did. Jang explains that girls are more likely than boys to refrain from expressing their sexuality, possibly because of the shame they think they may bring on themselves and their families. One girl, she recalled, fell in love with her godsister and wanted to tell her, but she was afraid that if she did, everyone in Chinatown would find out.

For both genders, though, coming out to family and friends is a huge issue, one that Virtucio says cannot be put off indefinitely. "Parents want to know," she said, adding that many AQUA members have told her that they suspected that their parents knew about their sexuality long before their children would admit it to themselves. Mothers, she said, might ask daughters questions like, "Why to you dress that way? Wear a skirt." Or they might tell their sons, "Don't walk like that." At the same time, she said, cultural pressures to put the family first or to hide one's feelings often convince Asian and Asian American youth to internalize their sexuality. Each family member often is expected to fill an explicit role. For example, she explained, a Filipina, particularly the first-born daughter, "is supposed to take care of the family, and get married and have kids." A first-born Chinese son, she added, "can never be gay. He is supposed to extend the family name."

Desmond Kwok says his parents accept his sexual orientation -- though they don't necessarily support him emotionally. He acknowledges an ongoing "starvation for love" that he blames on his parents. Both have been distant, he says, especially his father, a businessman who lives in Chicago. Kwok says he found support for coming out not from his family, but from a gang he was in two years ago. "They were really cool with it, and it boosted my confidence in the whole coming-out process," he said. "They'd say, 'If someone has a grudge against you for being gay, we're there for you. We'll kick their asses.' "

Now, Kwok dates "older" Asian and Asian American men -- at least 19 -- because few come out before then, he says. He admits that he has tried to find boyfriends over the Internet, at bars and cafes, "the worst places to meet a good boyfriend. A graduate of the School of the Arts, a magnet academy, Kwok said he intends to continue his work as an advocate for gay Asian and Asian American teens. Yet even now he cannot rid "the feeling of being alone -- being around people who really love you, but still knowing they are heterosexual. They'll be with their girlfriends or boyfriends, and here I am all alone, sitting around, boo-hoo, no boyfriend."

'Straight' Into Isolation, 'Out' Into Happiness

Eric Aquino never had such peer support growing up in Vallejo, Calif., and especially in junior high school. "I felt alone," Aquino said. He avoided his locker, where the popular kids hung out, and instead took long, circuitous paths to classes to dodge their cruel comments. "A good day for me was being able to walk down the hall without having anyone ask, 'Are you gay? Do you suck dick?' His grades fell. "I would be late to class and wouldn't bring my books," he explained. "I couldn't concentrate. I looked at the clock until it was 3 o'clock and time to go."

Aquino's high school years were both the happiest and one of the most depressing times of his life. He joined marching band and had friends for the first time, but he also started feeling that he was, in fact, gay. "Friends were important to me because I never had any, but they didn't know me for what I was," he said. Aquino thought perhaps he should wait until he was 18 to come out, so that if his parents rejected him, he could run away. He also considered living in the closet and spent much of his time thinking of ways to keep his secret. "I thought of different alternatives, other options. Like, I'll get married and have kids, [then divorce] and be a single parent, and my parents would just think I never found love again."

Thinking Sociologically

Once LGBTQ Asian Americans come out of the closet, do they find more support and acceptance within the mainstream LGBTQ community? Many do, but unfortunately, anti-Asian racism among the predominantly white LGBTQ community still exists. Joseph Erbentraut's article "Gay Anti-Asian Prejudice Thrives On the Internet " and Gay.net's article "Gay Racism Comes Out" provide insight into the challenges that LGBTQ Asian Americans face with regards to acceptance in the larger LGBTQ community. How are LGBTQ Asian Americans treated in the LGBTQ community in your city?

Ofiee Virtucio, 21, can relate to the feeling of isolation. "Maybe it's the feeling where you know you're Asian but sometimes in situations you're embarrassed to be," she said. "That's where I was for a long time. Of course I was lonely." When she was 13 and still in the Philippines, she recalls, her mother asked her, "Tomboy ca ba?' -- are you gay? She looked me in the eyes; she was worried," Virtucio said. "I said, 'No!' " She wishes that her mom had replied, "Whatever you are, it's OK. I still love you, Ofie.' " Two years later, the family came to the United States. "I had to be white in a month," she recalled. "When I started talking, I had an American accent that I could use, so I could make friends," she said. "During senior year, I was in denial being Filipino and didn't talk about being gay. Most importantly, I had to get friends. I had to get to know what America is all about. I had to survive."

She recalled: "I was trying to be straight but didn't want to have sex. I didn't want a man's penis in me." Though she had a boyfriend in high school, she secretly had crushes on girls, especially the teenage lesbians who were "out." At the same time, she recalls, she "couldn't relate. They were more 'we're-here-we're-queer' ... I knew I was gay, but I thought, 'I'm not like that.' It made me think I could never be like that." So, she said, "When my friends would talk about cute guys, I would jump into the conversation. I thought, 'OK, I have to do this right now,' so I'd say things like, 'Oh, he's so cute.' "Then when I would go home, I'd be like ... oh," said Virtucio, covering her eyes with her palms. "It hurts. It really, really hurts."

Virtucio finally acknowledged her sexuality during her college years, "the happiest time in my life." At age 18, she found her first girlfriend and experienced her first kiss, but it took many more years before she felt truly comfortable about being a lesbian. "I knew it was going to be a hard life," she said. "I thought, 'How am I going to tell my siblings? How am I going to get a job? Am I going to be constrained to having only gay friends? What are people going to think of me? I thought people would know now -- just because I know I'm gay -- that they'll just see it."

Virtucio never had the opportunity to come out to her mother, who passed away when she was 15. But in college, she did tell her father. She remembers he was in the garden watering plants when he asked her, out of the blue, whether her girlfriend was more than a friend. Startled, Virtucio says she denied it, but later that day, she opened the door to his bedroom and said it was true. They took a walk on the beach after that. "He told me whatever made me happy was fine," Virtucio recalls. "My father used to be mean to my mom, pot-bellied, chauvinistic," she says. "But for some reason he found it in his heart to understand. That moment was amazing for me. I thought if my dad could understand, I really don't care what the world thinks. I'm just going to be the person I am."

Contributors and Attributions

- Tsuhako, Joy. (Cerritos College)

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College)

- Asian Nation (Le) (CC BY-NC-ND) adapted with permission

Works Cited & Recommended for Further Reading

- Carnes, T. & Yang, F. (Eds.). (2004). Asian American Religions: The Making and Remaking of Borders and Boundaries. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Cho, S. (1997). Rice: Explorations into Asian Gay Culture & Politics. San Francisco, CA: Queer Press.

- Chou, R.S. (2012). Asian American Sexual Politics: The Construction of Race, Gender, and Sexuality. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Duncan, P. & Wong. G. (Eds). (2014). Mothering in East Asian Communities. Bradford, ON: Demeter Press.

- Eng, D.L. & Hom, A.Y. (Eds.). (1998). Q & A: Queer in Asian America. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Forbes, B.D., Mahan, J.H. (Eds.). (2017). Religion and Popular Culture in America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Fujiwara, L. & Roshanravan S. (Eds.). (2018). Asian American Feminisms and Women of Color Politics. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Hune, S. (Ed.). (2020). Our Voices, Our Histories: Asian American and Pacific Islander Women. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Kang, M. (2010). The Managed Hand: Race, Gender and the Body in Beauty Service Work. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Jeung, R. (2004). Faithful Generations: Race and New Asian American Churches. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Lee, J. & Zhou, M. (Eds.). (2004). Asian American Youth: Culture, Identity, and Ethnicity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Leong, R. (1995). Asian American Sexualities: Dimensions of the Gay and Lesbian Experience. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ling, H. (2007). Voices of the Heart: Asian American Women on Immigration, Work, and Family. Kirksville, MO:Truman State University Press.

- Mishima, Y. (1988). Confessions of a Mask. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Prasso, S. (2006). The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. New York, NY: Public Affairs Publishing.

- Quang, B., Yanagihara, H. & Liu, T. (Eds.). (2000). Take Out: Queer Writing from Asian Pacific America. New York, NY: Asian American Writers' Workshop.

- Seagrave, S. (1992). Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China. New York, NY: Knopf Books.

- Seidman, S. (2002). Beyond the Closet: The Transformation of Gay and Lesbian Life. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Shimizu, C. (2007). The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/American Women on Screen and Scene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stevenson, M.R. (2003). Everyday Activism: A Handbook for Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual People and Their Allies. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tan, J. (1998). Queer Papi Pørn: Gay Asian Erotica. Jersey City, NJ: Cleis Press.

- Toyama, N.A., Gee, T., Khang, K., de Leon, C.H., & Dean, A. (Eds.). (2005). More Than Serving Tea: Asian American Women on Expectations, Relationships, Leadership and Faith. Westmont, IL: IVP Books.

- Valverde, K., Linh, C. & Wei Ming, D. (Eds.). (2019). Fight the Tower: Asian American Women Scholars’ Resistance and Renewal in the Academy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Wat, E.C. (2002). Making of a Gay Asian Community: An Oral History of Pre-AIDS Los Angeles. New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield.