1.3: Who Has Power in U. S. Politics?

- Page ID

- 134520

“[America has] democracy by coincidence, in which ordinary citizens get what they want from government only when they happen to agree with elites or interest groups that are really calling the shots.”

— Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page (1)

“America’s political establishment has created vast inequities not only in the economy, but in criminal justice, (where street crime is heavily punished, but white collar crime is not), war (it’s mostly not the sons and daughters of politicians and CEOs getting killed in overseas conflicts), healthcare (where much of the population lives in fear that getting sick will trigger bankruptcy), debt forgiveness (Wall Street bailout recipients got to write off losses, but people suffering foreclosures and student loan defaults are ruined), and other arenas.”

–Matt Taibbi (2)

Theories About American Politics

Over the years, political analysts have tended to split over how the American political system operates. This split involves three theoretical systems: pluralism, hyper-pluralism, and the power elite. The disagreements center around which theory best describes what is really going on in American politics.

Pluralism is well represented by French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville’s insights into the vitality of early American politics. Convinced that France was moving towards social equality similar to American democracy, de Tocqueville toured the United States in the 1830s to analyze democracy as a political potential. He was struck by how well developed the principle of association—a proto form of pluralism—was among average Americans. At the time, American politics was marked by a rich diversity of organized associations and interest groups vying with each other to see that their respective wishes were translated into government policy. (3)

Pluralism is a theoretical approach that emphasizes how ordinary Americans are free to start or join any groups that share interests and whose struggles provide an even playing field with others. In other words, no one set of interests is likely to dominate public policy—at least not for very long, because the many losers will temporarily put aside their differences to collaborate to influence policy. The pluralist argument is bolstered by the number and variety of interest groups and by the fact that interests in one category—business, for example—often struggle with each other.

Political scientists argue that the United States was at some point characterized by pluralism, but over time it transformed into something less healthy: an out-of-control hyper-pluralist polity. Hyper-pluralism suggests that the government has essentially been captured by the demands of interest groups. Rather than arbitrating the struggle between organized interests, the government tries to put into effect the wishes of all groups to the detriment of the country. (This concept may also be referred to as interest-group liberalism.) (4) These actions may be contradictory. For example, spending money to subsidize fossil fuel extraction while at the same time passing regulations to limit carbon emissions. As you can see, there isn’t really a competition going on as envisioned by pluralism. The hyper-pluralism system more closely resembles a free-for-all.

The third approach is called elite theory. Elite theorists hold that the pluralists and the hyper-pluralists fail to accurately show what is really going on: that a relatively small and wealthy class of individuals—the power elite—prevails. (5) In other words, the power elite are either the decision-makers or they so influence the decision-makers that the elites get their way most of the time.

Elite theory highlights how business interests create interlocking and overlapping connections that reinforce their position and allow them to control the political system, such as the exclusive and overlapping memberships of corporate boards, foundation boards, and trustee positions for public and private universities, as well as corporate media ownership. The fact that elites have disproportionate power and seek to continue their dominance is not new. As political essayist Noam Chomsky wrote, “Right through American history, there’s been an ongoing clash between pressure for more freedom and democracy coming from below and efforts at elite control and domination coming from above.” (6)

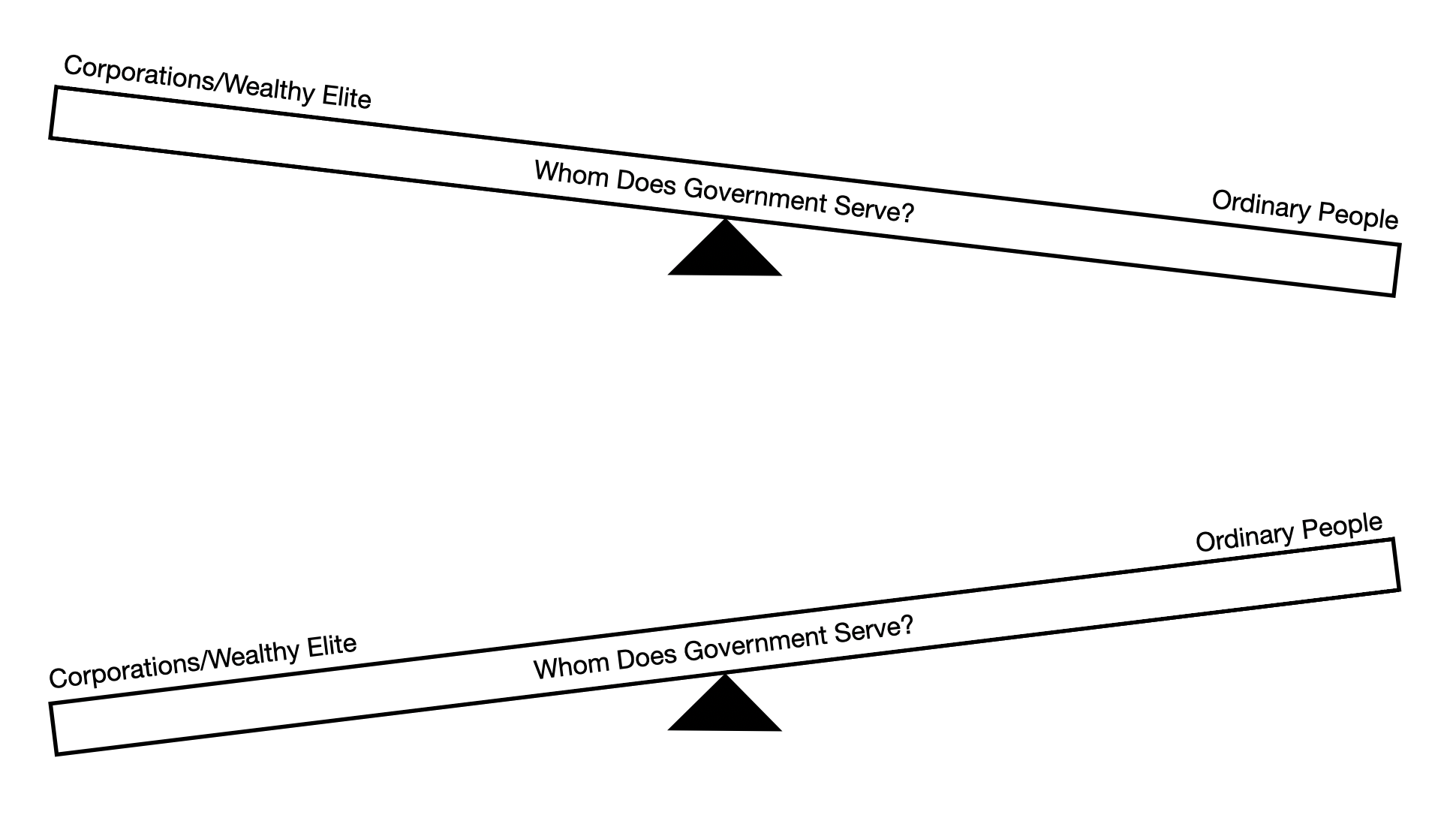

Think of elite theory as a teeter-totter in a public park. On one end sit large corporations and the elite, which is composed of a very small number of families firmly entrenched in the top five percent of the U.S' income and wealth distribution. On the other end sit ordinary Americans, comprised of everyone from an emergency room doctor with a very comfortable income, or a college student living in her car and working for minimum wage at a big box store. In whose interest does government work?

According to the bottom image, based on elite theory, the government primarily operates in the interest of corporations and the wealthy elite. Even though there are far fewer people on the elite side of the teeter-totter, they weigh more in the deliberations of government than do the interests of the majority of the population.

Some people would argue that the aim of democratic engagement should be to better balance the teeter-totter and see government serve the broad interests that ordinary Americans have for true equality of opportunity, healthcare, education, and an economy that provides a decent life for all.

Applying the Three Dimensions of Power

Why study the elite theory perspective? How is this theoretical lens useful in studying the three dimensions? Public policy—the results of decision-making—tilts toward the interests of the elite. This action is the first dimension of power. With respect to the second dimension of power, we’d expect the rules of the game to be tilted in favor of elites getting what they want while hindering what ordinary people want. Lastly, through the third dimension of power, we would expect to see ordinary people taking on the viewpoints of the elites against their own interests.

Let’s look at the first dimension of power. According to political scientist Michael Parenti, “every year the federal government doles out huge sums in corporate welfare in the form of tax breaks, price supports, loan guarantees, bailouts, payments-in-kind, subsidized insurance rates, marketing services, export subsidies, irrigation and reclamation programs, and research and development grants.” (7) The public cost of corporate welfare is enormous, and there are two immediate effects. First, the welfare that corporations receive is rarely translated into lower prices for consumers. Instead, it provides better dividends for stockholders and higher salaries for their upper-level employees, who are already in the upper 10 percent of wage earners. Secondly, corporate welfare translates into ordinary people making up for the lost revenues from corporate tax giveaways.

As for the second dimension of power, the constitutional system is stacked in favor of elites being able to stop action. Because the American electoral system runs on money, “both major parties tend to be corrupted—and pushed away from satisfying the needs and wishes of ordinary Americans—by their reliance on wealthy contributors.” (8) Corporate media systems ensure that progressive ideas have a more difficult time getting heard. The system of organized interest groups is heavily stacked in favor of business groups and the wealthy.

The third dimension of power is the easiest to see. Working people have been marshaled by elites to support other tax breaks, limitations on unions, free-trade agreements, and cuts to the social safety net. Economists Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky (9) argued that political consent... is manufactured through election campaigns that focus on superficial considerations." Consent is also manufactured by frightening people or by getting them angry. Want to cut public assistance for the poor? Get people upset about “welfare queens.” Want to invade a country? Talk about that country’s leader being “worse than [insert dictator's name],” and posing an existential threat to the United States. Want to increase gun sales and defeat attempts to regulate firearms? Talk about crime. It works just as well when crime is at record lows as when crime is high. All these measures have been successful. These measures only require that you control the media, decide what issues get addressed, and how those issues are framed. Elites have that kind of control.

Even the partisan stalemate in Washington—which is not a myth, but has taken on mythic proportions—plays into the hands of the elites because it creates a sense of futility among many people, a feeling that “politicians are all the same” or “it doesn’t matter who wins elections, so I might as well not vote.” The political demobilization of ordinary people is perhaps the best tool the wealthy and corporations have to achieve their aims. As South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko said, “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” (10) If the governed can be made to feel that they are powerless to effect change, then indeed they are powerless.

The People and the Elites

Throughout U.S. history, popular will has translated into public policies that benefited average men and women over the elites. People have risen up and demanded protection from monopoly corporate power, a minimum wage, worker safety laws, and laws against child labor. Women demanded the right to vote. People of all races demanded civil rights laws that guaranteed voting privileges, the right to equality in the workplace, the right to go to neighborhood schools, and freedom from sexual harassment. People demanded that the impoverishment of the elderly be ameliorated—and it was through programs like Social Security and Medicare. While elites have the most power in the U.S. system, the majority has organized itself to protect its interests.

While elites have disproportionate power, we don’t need to make conclusions about the character of corporate executives, hedge fund directors, Wall Street bankers, or Silicon Valley titans. Like any group of people, the elite encompasses upstanding, exemplary individuals as well as those whose motives are less than admirable. The question for a political system is whether concentrations of economic and political power can coexist with democracy. Will the self-interest of a powerful elite—a minority of the population—distort the political and economic rules in ways that perpetuate vast inequality? Political philosopher, Danielle Allen put the challenge this way:

“A proper role of government—nearly forgotten today, but the overriding concern of the Founders—is finding ways to prevent undue concentrations of power wherever they occur. Power tends toward self-perpetuation; where it is left undisturbed, it will draw further advantages to itself, shut out rivals, and mete out ever-bolder forms of injustice.” (11)

What if . . . ?

Imagine yourself in a national leadership role. What role would it be? Senator? Representative? President? Supreme Court Justice? How would you use your understanding of who has power in the United States to enhance the collective voice of ordinary Americans? How would you use it to, in Danielle Allen’s words, “prevent undue concentrations of power?”

References

- Martin Gilensand Benjamin Page, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” Perspectives on Politics. Fall 2014.

- Matt Taibbi, “Deval Patrick’s Candidacy is Another Chapter in the Democrats’ 2020 Clown Car Disaster,” Rolling Stone. November 14, 2019.

- Classic texts in the pluralist tradition include David B. Truman, The Governmental Process, 2nd edition. New York: Knopf, 1971; and Robert Dahl, Pluralist Democracy in the United States. Chicago: Rand-McNally, 1967.

- Theodore J. Lowi, The End of Liberalism, 2nd edition. New York: Norton: 1979.

- See C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956; and Ralph Miliband, The State in Capitalist Society. New York: Basic Books, 1969.

- Noam Chomsky, Requiem for the American Dream. The 10 Principles of Concentration of Wealth and Power. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2017. Page 1.

- Michael Parenti, Democracy for the Few. 9thedition. Boston: Wadsworth, 2011. Page 60.

- Benjamin I. Page and Martin Gilens, Democracy in America? What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do About It. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017. Page 111.

- Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon, 2012.

- Takudzwa Hillary Chiwanza, The African Exponent. September 12, 2017.

- Danielle Allen, “The Road From Serfdom,” The Atlantic. December2019.

Media Attributions

- Teeter Totter Graphic © David Hubert is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license