8.1: What Is Public Policy?

- Page ID

- 147653

When designers engineer a product, like a car, they do so with the intent of satisfying the consumer. But the design of any complicated product must take into account the needs of regulators, transporters, assembly line workers, parts suppliers, and myriad other participants in the manufacture and shipment process. In addition, manufacturers must also be aware that consumer tastes are fickle: A gas-guzzling sports car may appeal to an unmarried twenty-something with no children; but what happens to product satisfaction when gas prices fluctuate, or the individual gets married and has children?

In many ways, the process of designing domestic policy isn’t that much different. Just like auto companies, the government needs to ensure that its citizen-consumers have access to an array of goods and services. And just as in auto companies, a wide range of actors is engaged in figuring out how to do it. Sometimes, this process effectively provides policies that benefit citizens. But just as often, policymaking is muddied by the demands of competing interests with different opinions about society’s needs or the role that government should play in meeting them. To understand why, we begin by thinking about the meaning of “public policy.”

Public Policy Defined

Public policy is a guide to legislative action that is more or less fixed for long periods of time, not just short-term fixes or single legislative acts. Policy also doesn’t happen by accident, and it is rarely formed simply as the result of the campaign promises of a single elected official, even the president. While elected officials are often important in shaping policy, most policy outcomes are the result of considerable debate, compromise, and refinement that happen over years and are finalized only after input from multiple institutions within government as well as from interest groups and the public.

Consider the example of health care expansion. A follower of politics in the news media may come away thinking the reforms implemented in 2010 were sudden, having been developed in the final weeks before they were enacted. The reality is that expanding health care access had been a priority of the Democratic Party for several decades. Even before passage of the Affordable Care Act (2010), also referred to as Obamacare, more than 50 percent of all health care expenditures in the United States already came from federal government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. In addition, much of ACA was drawn from proposals originally developed at the state level, by none other than Obama’s 2012 Republican presidential opponent Mitt Romney when he was governor of Massachusetts.[1]

Governments frequently interact with individual actors like citizens, corporations, or other countries. They may even pass highly specialized pieces of legislation, known as private bills, which confer specific privileges on individual entities. But public policy covers only those issues that are of interest to larger segments of society or that directly or indirectly affect society as a whole. Paying off the loans of a specific individual would not be public policy, but creating a process for loan forgiveness available to certain types of borrowers (such as those who provide a public service by becoming teachers) would certainly rise to the level of public policy.

A final important characteristic of public policy is that it is more than just the actions of government; it also includes the behaviors or outcomes that government action creates. Policy can even be made when the government refuses to act in ways that would change the status quo when circumstances or public opinion begin to shift.[2] For example, much of the debate over gun safety policy in the United States has centered on the unwillingness of Congress to act, even in the face of public opinion that supports some changes to gun policy. In fact, one of the last major changes occurred in 2004, when lawmakers’ inaction resulted in the expiration of a piece of legislation known as the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (1994).[3]

Update: On June 25, 2022, President Biden signed a new law, ending nearly three decades of gridlock over how to address gun violence in the United States. The bipartisan gun deal includes millions of dollars for mental health, school safety, crisis intervention programs, and incentives for states to include juvenile records in the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. The law does not ban any specific weapons. Source

Public Policy as Outcomes

Typically, elected and even high-ranking appointed officials lack either the specific expertise or tools needed to successfully create and implement public policy on their own. Instead, the vast government bureaucracy provides policy guidance. For example, when Congress passed the Clean Water Act (1972), it dictated that steps should be taken to improve water quality throughout the country. But it ultimately left it to the bureaucracy to figure out exactly how ‘clean’ water needed to be. In doing so, Congress provided the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) with discretion to determine how much pollution is allowed in U.S. waterways.

Policy outcomes can be talked about in terms of winners and losers. Almost by definition, public policy promotes certain types of behavior while punishing others. So, the individuals or corporations that a policy favors are most likely to benefit, or win, whereas those the policy ignores or punishes are likely to lose. Even the best-intended policies can have unintended consequences and may ultimately harm someone. A policy designed to encourage students to go to liberal arts colleges may cause trade school enrollment to decline. Efforts to clean up drinking water supplies may make companies less competitive and cost employees their livelihood. Even something that seems to help everyone, such as promoting charitable giving through tax incentives, runs the risk of lowering tax revenues from the rich (who contribute a greater share of their income to charity) and shifting tax burdens to the poor (who must spend a higher share of their income to achieve a desired standard of living). While policy pronouncements and bureaucratic actions are certainly meant to rationalize policy, it is whether a given policy helps or hurts constituents (or is perceived to do so) that ultimately determines how voters will react toward the government in future elections.

The Social Safety Net

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the United States created a set of policies and programs that constituted a social safety net for the millions who had lost their jobs, their homes, and their savings. Under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the federal government began programs like the Work Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps to combat unemployment and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to refinance Depression-related mortgage debts. As the effects of the Depression eased, the government phased out many of these programs. Other programs, like Social Security or the minimum wage, remain an important part of the way the government takes care of the vulnerable members of its population. The federal government has also added further social support programs, like Medicaid, Medicare, and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, to ensure a baseline or minimal standard of living for all, even in the direst of times.

In recent decades, some people have criticized these safety net programs for inefficiency and for incentivizing welfare dependence. Critics deeply resent the use of taxpayer money to relieve social problems like unemployment and poverty; workers who may themselves be struggling to put food on the table or pay the mortgage feel their hard-earned money should not support other families. “If I can get by without government support,” the reasoning goes, “those welfare families can do the same. Their poverty is not my problem.”

So where should the government draw the line? While there have been some instances of welfare fraud, the welfare reforms of the 1990s have made long-term dependence on the federal government less likely as the welfare safety net was pushed to the states. With the income gap between the richest and the poorest at its highest level in history, this topic is likely to continue to receive much discussion in the coming years.

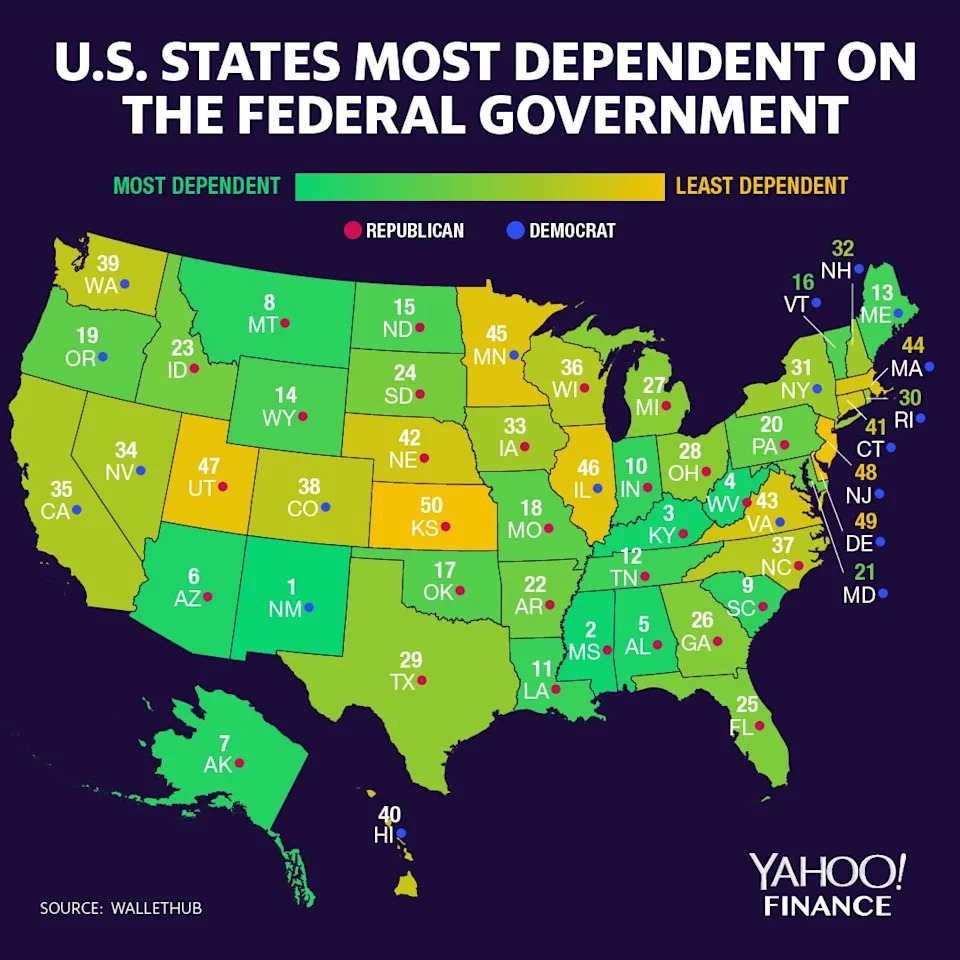

Special Report: Dependency on the Federal Government

Federal assistance to states came into the spotlight during the coronavirus pandemic, when some states received far more money per case than others from the stimulus packages. However, Americans have looked at federal assistance programs with growing scrutiny for years, and the number of people dependent on government assistance was decreasing prior to the coronavirus crisis. Regardless of overall trends, though, it is clear that some states receive a far higher return on their federal income-tax contributions than others. To see the 2022 Report, click here.

The 2019 Results are shown below.

Link to Learning

Explore historical data on United States budgets and spending from 1940 to the present from the Office of Management and Budget.

Resources

- "Romneycare vs. Obamacare: Key Similarities & Differences," 13 November 2013. http://boston.cbslocal.com/2013/11/13/romneycare-vs-obamacare-key-similarities-differences/ (March 1, 2016). ↵

- E. E. Schattschneider. 1960. The Semi-Sovereign People. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ↵

- Brad Plumer, "Everything you need to know about the assault weapons ban, in one post," The Washington Post, 17 December 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2012/12/17/everything-you-need-to-know-about-banning-assault-weapons-in-one-post/ (March 1, 2016). ↵

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). ↵

- American Government 2e. Authored by: OpenStax. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/nY32AU8S@5.1:xJJkKaSK@5/Preface. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9d8df601-4f1...50bf739e5f@5.1