6.5: Economics and Globalization in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Page ID

- 131902

Formal colonization of Africa ended in 1980. In many areas, it was replaced with neocolonialism, the practice of exerting economic rather than direct political control over territory. Today, most of Sub-Saharan Africa’s exports remain raw materials. As a result, the economies of countries in the region are vulnerable to price fluctuations and global markets. Furthermore, although Western countries no longer directly control African land, corporations based in these countries have either bought land directly or invested heavily in the region. Investors have also purchased the water rights to some areas.

Neocolonialism is also evidenced on a broader scale. The peripheral regions of the world generally supply goods and labor used by the core countries. Thus, the core continues to exert economic pressure on the periphery to maintain beneficial trade partnerships and cheap products, labor, and raw materials. In many countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, a dual economy exists, where plantations or commercial agriculture is practiced alongside traditional agricultural methods.

South Africa’s dual economy has created dramatic differences in development within its own borders and has exacerbated income inequality in the country. Critics of neocolonial theory argue that too much blame is placed on colonialism for the modern economic problems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, government corruption, inefficiency, and internal exploitation remain significant barriers to long-term economic development.

In some cases, economic pressure has come from loans granted by the core to the periphery. Although the intention of these loans was to assist the periphery in infrastructure development, many countries have struggled under the weight of staggering debt. Two leading organizations in particular, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, have loaned over $150 billion to countries in Africa. Loans by the IMF and World Bank to countries experiencing economic crises are accompanied by structural adjustment programs (SAPs), stipulating economic changes a country must make in order to make it better able to repay its loans. These conditions might include decreasing wages, rising food prices, or making the economy more market-oriented.

In practice, though, structural adjustment programs limit the ability of states to make their own economic decisions, which some see as neocolonialism. In addition, SAPs require governments to drastically cut their spending, which most often leads to cuts in social services and public health. These austerity measures can lead to economic stagnation, ultimately hampering a country’s ability to pay back its loans – the very thing the SAPs were designed to do. Furthermore, aid packages and loan programs were generally designed to reflect Western ideas of development, possible evidence of neocolonialism in the region.

For some countries, the interest payments alone far exceed what they are able to pay. Globally, 39 countries, 33 of which are in Sub-Saharan Africa, have been identified as heavily indebted poor countries and eligible for debt relief through a joint venture by IMF and World Bank. Changes have been made to the program to specifically address poverty in these countries and shift the loan payment amounts to funding for social and public services.

Increasingly, African countries are partnering with investment groups rather than lending organizations and private investment. China is Africa’s largest trading partner and the country has invested billions in African infrastructure projects and direct aid. Chinese investment projects include a $12 billion coastal railway in Nigeria and a $7 billion “mini city” in South Africa. In Angola, Chinese investors built Kilamba New City, a town complete with 25,000 homes, schools, and commercial facilities, to be repaid by Angolan oil (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

For low-income individuals in Sub-Saharan Africa, microfinance has provided a way to access a range of financial and investment services. These services might include small loans, known as microcredit. Women, in particular, have benefited from microcredit, which does not require complex paperwork, extensive employment history, or collateral as with traditional loans, but has provided a way for women to become entrepreneurs. Interest rates on these loans are generally quite small, and over 95 percent of loans are repaid. Globally, microcredit loans totaled $38 billion in 2009. Globally, most of the 150 million microfinance clients are in Asia, but its presence in Africa is growing.

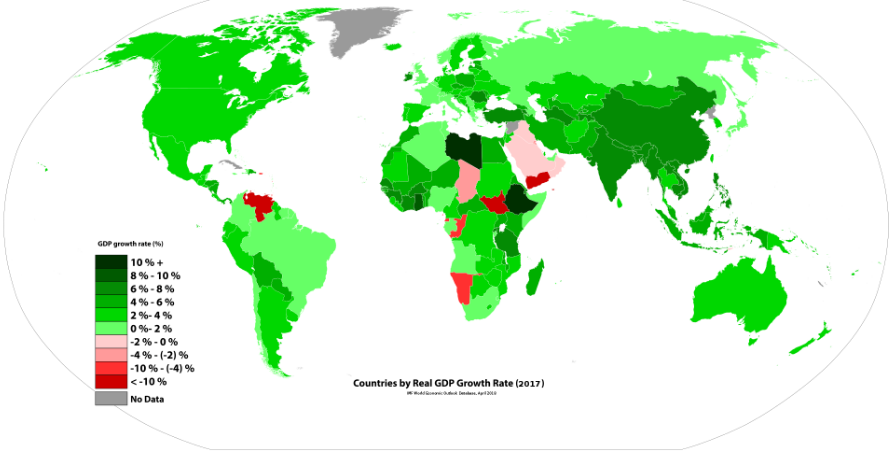

Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the fastest developing regions in the world with a 4 percent growth rate in 2016 compared to a global average of 3.4 percent (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Despite significant mineral, agricultural, and energy resources, most people in the region remain impoverished. Africa’s leading export is petroleum and petroleum products, and yet most Africans do not have access to a reliable source of electricity. Political instability has limited the benefit of economic growth for many low-income Africans.

Economic growth, if invested in infrastructure and public services, combined with increased educational and career training opportunities could improve incomes in the region. According to current estimates, by the end of this century, Africa’s population will quadruple. This rapid population growth coupled with continued economic development could dramatically reshape the African geographic landscape.

- Neocolonialism:

-

the practice of exerting economic rather than direct political control over territory

- Dual Economy:

-

when plantations or commercial agriculture is practiced alongside traditional agricultural methods

- Structural Adjustment Programs:

-

a set of required economic changes that accompany a loan made by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to a country that is experiencing an economic crisis

- Microfinance:

-

financial and investment services for individuals and small businesses who otherwise do not have access to traditional banking services