18.5: Cold War in the United States

- Page ID

- 132610

During a speech, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy waved a sheet of paper in the air, and falsely announced that he was holding a list of 205 names “that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping [U.S.] policy.” Since McCarthy had no actual list, the number quickly changed to fifty-seven, then eighty-one. Finally, he promised to disclose the name of just one communist, the nation’s “top Soviet agent.” The shifting numbers brought ridicule, but it didn’t matter: McCarthy’s lies won him fame and fueled a new “Red Scare.”

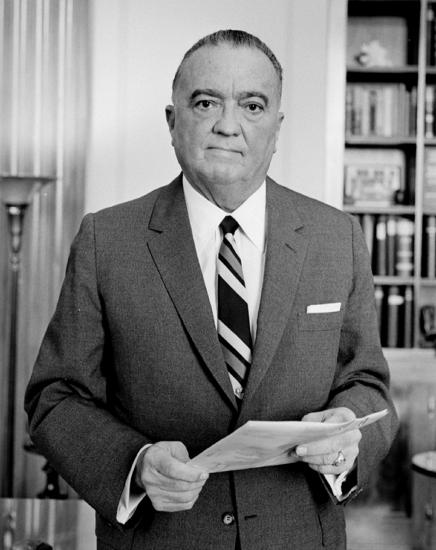

McCarthyism was part of a widespread anti-communist propaganda campaign directed by the U.S. government. Starting in 1956, the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) began a counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO, to disrupt the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA). The scope of COINTELPRO’s targets grew to include civil rights groups, feminists, environmentalists, Native American activists, and anti-war protestors. The program was formally dissolved in 1971. Many people believed the FBI had greatly overstepped its authority.

In Congress, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations held over a hundred investigations and hearings on communist influence in American society between 1949 and 1954. The Internal Security Act of 1950 required all “communist organizations” to register with the government, gave the government greater powers to investigate sedition, and made it possible to prevent suspected individuals from gaining or keeping their citizenship. In the first year, the new law turned away over 50,000 immigrants from Germany and over 10,000 displaced Russians.

There were, of course, communists in the United States. The CPUSA enjoyed most of its influence as labor organizers and as strong opponents of Jim Crow segregation. But even at the height of the Depression, communism never attracted many Americans. McCarthy’s and Hoover’s witch-hunts hurled accusations and ruined careers less on people’s communist sentiments and more on their opposition to civil rights and anti-war protestors.

Arms Race and Space Race

The so-called Arms Race was not only about nuclear technology, but also a contest to improve the distance and accuracy of missiles that could carry a nuclear load. This race led indirectly to the Space Race, as both the U.S. and the Soviets initiated programs for space exploration.

At the end of World War II, as Germany collapsed, the United States and the Soviet Union had raced toward Berlin, hoping to acquire elements of the Nazi V-2 missile program and jet propulsion project. The Nazis had developed a “vengeance weapon” to terrorize England (but never used it). The V-2 was the world’s first guided ballistic missile, capable of carrying an explosive payload up to six hundred miles.

Germany’s top rocket scientist, Wernher von Braun, surrendered to U.S. troops and eventually became the leader of the American space program. About 1,600 German scientists and engineers found their way into the American program. The Soviet Union’s program was managed by Red Army colonel Sergei Korolev, and employed about 2,000 Germans. Both engineering teams worked to adapt German rocket technology to create an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) that could carry the new nuclear weapons.

Jet technology developed even more rapidly. By the time of the Korean War (150-1953), jet fighters supported both sides, using identical German technology acquired after World War II. Commercial jetliners were introduced in the 1950s, replacing ocean liners as long-distance passenger transport by the 1970s.

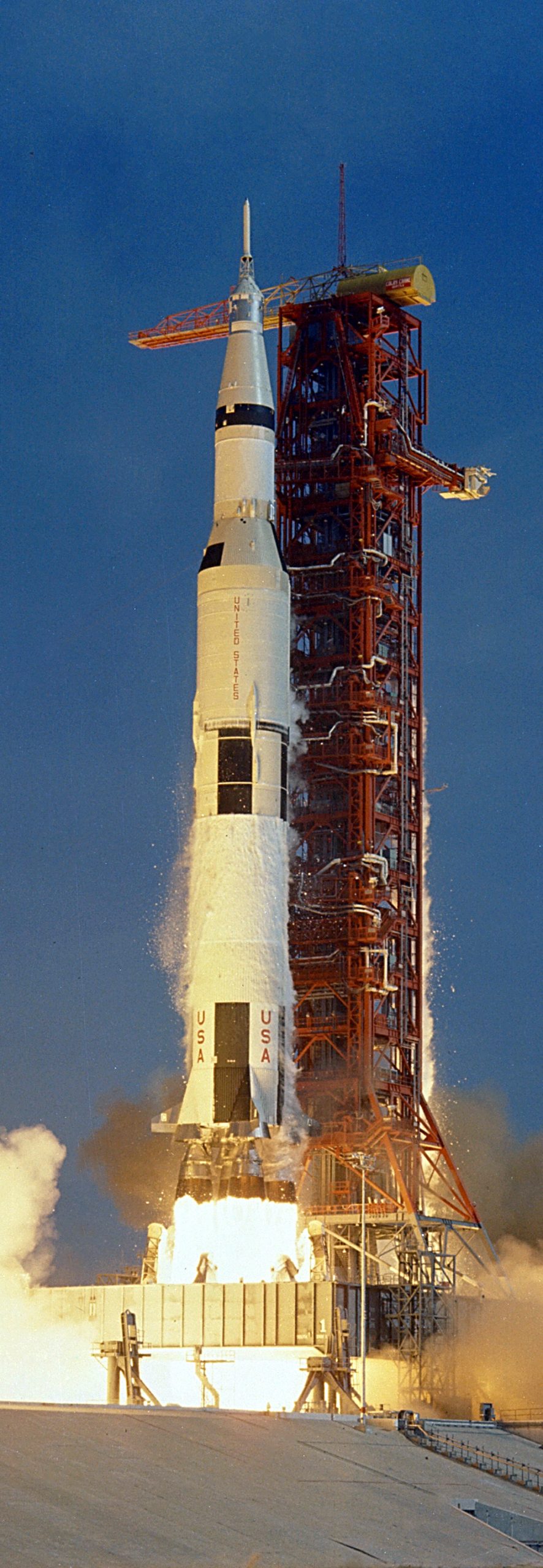

When it came to the missile race, the Soviets came in first. They even used the ICBM launch vehicle in October 1957, to send Sputnik, the world’s first human-made satellite, into orbit. It was a decisive technological victory, and the Soviet propaganda ministry took full advantage of the opportunity to begin a space race while at the same time warning the U.S. that it could deliver nuclear weapons to American targets.

In response, the U.S. government rushed to perfect its own ICBM technology. In 1958, it established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to launch satellites and astronauts into space. The initial U.S. attempts to launch a satellite into orbit suffered spectacular failures, heightening fears of Soviet domination in space. While the U.S. space program struggled, the Soviet Union’s Luna 2 capsule became the first human-made object to touch the moon in September 1959. Then the U.S.S.R. successfully launched a pair of dogs (Belka and Strelka) into orbit and returned them to Earth alive in August 1960 while the U.S. Mercury program languished behind schedule.

Next came the launching of human presence in space. Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was launched into orbit on April 12, 1961. U.S. astronaut Alan Shepard accomplished a suborbital flight in the Freedom 7 capsule on May 5. The United States had been embarrassed, and John Kennedy used America’s frustration over early losses in the “space race” to bolster funding for a manned moon landing, which succeeded on July 20, 1969.