3.3: Communication and Relational Dispositions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 115932

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- List and explain the different personality traits associated with Daly’s communication dispositions.

- List and explain the different personality traits associated with Daly’s relational dispositions.

In the previous section, we explored the importance of temperament, cognitive dispositions, and personal-social dispositions. In this section, we are going to explore the last two dispositions discussed by John Daly: communication and relational dispositions.68

Communication Dispositions

Now that we’ve examined cognitive and personal-social dispositions, we can move on and explore some intrapersonal dispositions studied specifically by communication scholars. Communication dispositions are general patterns of communicative behavior. We are going to explore the nature of introversion/extraversion, approach and avoidance traits, argumentativeness/verbal aggressiveness, and lastly, sociocommunicative orientation.

Introversion/Extraversion

The concept of introversion/extraversion is one that has been widely studied by both psychologists and communication researchers. The idea is that people exist on a continuum that exists from highly extraverted (an individual’s likelihood to be talkative, dynamic, and outgoing) to highly introverted (an individual’s likelihood to be quiet, shy, and more reserved). Before continuing, take a second and fill out the Introversion Scale created by James C. McCroskey and available on his website (http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measu...troversion.htm). There is a considerable amount of research that has found an individual’s tendency toward extraversion or introversion is biologically based.69 As such, where you score on the Introversion Scale may largely be a factor of your genetic makeup and not something you can alter greatly.

When it comes to interpersonal relationships, individuals who score highly on extraversion tended to be perceived by others as intelligent, friendly, and attractive. As such, extraverts tend to have more opportunities for interpersonal communication; it’s not surprising that they tend to have better communicative skills when compared to their more introverted counterparts.

Approach and Avoidance

Traits The second set of communication dispositions are categorized as approach and avoidance traits. According to Virginia Richmond, Jason Wrench, and James McCroskey, approach and avoidance traits depict the tendency an individual has to either willingly approach or avoid situations where he or she will have to communicate with others.70 To help us understand the approach and avoidance traits, we’ll examine three specific traits commonly discussed by communication scholars: shyness, communication apprehension, and willingness to communicate.

Shyness

In a classic study conducted by Philip Zimbardo, he asked two questions to over 5,000 participants: Do you presently consider yourself to be a shy person? If “No,” was there ever a period in your life during which you considered yourself to be a shy person?71 The results of these two questions were quite surprising. Over 40% said that they considered themselves to be currently shy. Over 80% said that they had been shy at one point in their lifetimes. Another, more revealing measure of shyness, was created by James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond and is available on his website (http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/shyness.htm).72 Before going further in this chapter, take a minute and complete the shyness scale.

According to Arnold Buss, shyness involves discomfort when an individual is interacting with another person(s) in a social situation.73 Buss further clarifies the concept by differentiating between anxious shyness and self-conscious shyness. Anxious shyness involves the fear associated with dealing with others face-to-face. Anxious shyness is initially caused by a combination of strangers, novel settings, novel social roles, fear of evaluation, or fear of self-presentation. However, long-term anxious shyness is generally caused by chronic fear, low sociability, low self-esteem, loneliness, and avoidance conditioning. Self-conscious shyness, on the other hand, involves feeling conspicuous or socially exposed when dealing with others face-to-face. Self-conscious shyness is generally initially caused by feelings of conspicuousness, breaches of one’s privacy, teasing/ridicule/bullying, overpraise, or one’s foolish actions. However, long-term self-conscious shyness can be a result of socialization, public self-consciousness, history of teasing/ridicule/bullying, low self-esteem, negative appearance, and poor social skills.

Whether one suffers from anxious or self-conscious shyness, the general outcome is a detriment to an individual’s interpersonal interactions with others. Generally speaking, shy individuals have few opportunities to engage in interpersonal interactions with others, so their communicative skills are not as developed as their less-shy counterparts. This lack of skill practice tends to place a shy individual in a never-ending spiral where he or she always feels just outside the crowd.

Communication Apprehension

James C. McCroskey started examining the notion of anxiety in communicative situations during the late 1960s. Since that time, research on communication apprehension has been one of the most commonly studied variables in the field. McCroskey defined communication apprehension as the fear or anxiety “associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons.”74 Although many different measures have been created over the years examining communication apprehension, the most prominent one has been James C. McCroskey’s Personal Report of Communication Apprehension-24 (PRCA-24).75 If you have not done so already, please stop reading and complete the PRCA-24 before going further (http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/prca24.htm).

The PRCA-24 evaluates four distinct types of communication apprehension (CA): interpersonal CA, group CA, meeting CA, and public CA. Interpersonal CA is the one most important to us within this textbook because it examines the extent to which individuals experience fear or anxiety when thinking about or actually interacting with another person (For more on the topic of CA as a general area of study, read Richmond, Wrench, and McCroskey’s book, Communication Apprehension, Avoidance, and Effectiveness76). Interpersonal CA impacts people’s relationship development almost immediately. In one experimental study, researchers paired people and had them converse for 15 minutes. At the end of the 15-minute conversation, the researchers had both parties rate the other individual. The results indicated that high-CAs (highly communicative apprehensive people) were perceived as less attractive, less trustworthy, and less satisfied than low-CAs (people with low levels of communication apprehension).77 Generally speaking, high-CAs don’t tend to fare well in most of the research in interpersonal communication. Instead of going into too much detail at this point, we will periodically revisit CA as we explore several different topics in this book.

Research Spotlight

In 2019, Jason Wrench, Narissra, Punyanunt-Carter, and Adolfo Garcia examined the relationships between mindfulness and religious communication. For our purposes, the researchers examined an individual’s religious CA, or the degree to which people were anxious about communicating with another person about their personally held religious beliefs. In this study, mindful describing and nonreactivity to inner experience was found to be negatively related to religious CA. As the authors note, “mindfulness can help people develop more confidence to communicate their ideas and opinions about religion. Therefore, people would be less apprehensive about communicating about religion” (pg. 13).

Wrench, J. S., Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., & Garcia, A. J. (2019). Understanding college students’ perceptions regarding mindfulness: The impact on intellectual humility, faith development, religious communication apprehension, and religious communication. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00861-3

Willingness to Communicate

The final of our approach and avoidance traits is the willingness to communicate (WTC). James McCroskey and Virginia Richmond originally coined the WTC concept as an individual’s predisposition to initiate communication with others.78 Willingness to communicate examines an individual’s tendency to initiate communicative interactions with other people. Take a minute and complete the WTC scale available from James C. McCroskey’s website (http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/WTC.htm).

People who have high WTC levels are going to be more likely to initiate interpersonal interactions than those with low WTC levels. However, just because someone is not likely to initiate conversations doesn’t mean that he or she is unable to actively and successfully engage in interpersonal interactions. For this reason, we refer to WTC as an approach trait because it describes an individual’s likelihood of approaching interactions with other people. As noted by Richmond et al., “People with a high WTC attempt to communicate more often and work harder to make that communication effective than people with a low WTC, who make far fewer attempts and often aren’t as effective at communicating.” 79

Argumentativeness/Verbal Aggressiveness

Starting in the mid-1980s, Dominic Infante and Charles Wigley defined verbal aggression as “the tendency to attack the self-concept of individuals instead of, or in addition to, their positions on topics of communication.”80 Notice that this definition specifically is focused on the attacking of someone’s self-concept or an individual’s attitudes, opinions, and cognitions about one’s competence, character, strengths, and weaknesses. For example, if someone perceives themself as a good worker, then a verbally aggressive attack would demean that person’s quality of work or their ability to do future quality work. In a study conducted by Terry Kinney,81 he found that self-concept attacks happen on three basic fronts: group membership (e.g., “Your whole division is a bunch of idiots!”), personal failings (e.g., “No wonder you keep getting passed up for a promotion!”), and relational failings (e.g., “No wonder your spouse left you!”).

Now that we’ve discussed what verbal aggression is, we should delineate verbal aggression from another closely related term, argumentativeness. According to Dominic Infante and Andrew Rancer, argumentativeness is a communication trait that “predisposes the individual in communication situations to advocate positions on controversial issues, and to attacking verbally the positions which other people take on these issues.”82You’ll notice that argumentativeness occurs when an individual attacks another’s positions on various issues; whereas, verbal aggression occurs when an individual attacks someone’s self-concept instead of attack another’s positions. Argumentativeness is seen as a constructive communication trait, while verbal aggression is a destructive communication trait.

Individuals who are highly verbally aggressive are not liked by those around them.83Researchers have seen this pattern of results across different relationship types. Highly verbally aggressive individuals tend to justify their verbal aggression in interpersonal relationships regardless of the relational stage (new vs. long-term relationship).84 In an interesting study conducted by Beth Semic and Daniel Canary, the two set out to watch interpersonal interactions and the types of arguments formed during those interactions based on individuals’ verbal aggressiveness and argumentativeness.85 The researchers had friendshipdyads come into the lab and were asked to talk about two different topics. The researchers found that highly argumentative individuals did not differ in the number of arguments they made when compared to their low argumentative counterparts. However, highly verbally aggressive individuals provided far fewer arguments when compared to their less verbally aggressive counterparts. Although this study did not find that highly argumentative people provided more (or better) arguments, highly verbally aggressive people provided fewer actual arguments when they disagreed with another person. Overall, verbal aggression and argumentativeness have been shown to impact several different interpersonal relationships, so we will periodically revisit these concepts throughout the book.

Sociocommunicative Orientation

In the mid to late 1970s, Sandra Bem began examining psychological gender orientation.86 In her theorizing of psychological gender, Bem measured two constructs, masculinity and femininity, using a scale she created called the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI–garote.bdmonkeys.net/bsri.html). Her measure was designed to evaluate an individual’s femininity or masculinity. Bem defined masculinity as individuals exhibiting perceptions and traits typically associated with males, and femininity as individuals exhibiting perceptions and traits usually associated with females. Individuals who adhered to both their biological sex and their corresponding psychological gender (masculine males, feminine females) were considered sex-typed. Individuals who differed between their biological sex and their corresponding psychological gender (feminine males, masculine females) were labeled cross-sex typed. Lastly, some individuals exhibited both feminine and masculine traits, and these individuals were called androgynous.

Virginia Richmond and James McCroskey opted to discard the biological sex-biased language of “masculine” and “feminine” for the more neutral language of “assertiveness” and “responsiveness.”87 The combination of assertiveness and responsiveness was called someone’s sociocommunicative orientation, which emphasizes that Bem’s notions of gender are truly representative of communicator traits and not one’s biological sex. Before talking about the two factors of sociocommunicative orientation, please take a few minutes to complete the Sociocommunicative Orientation Scale (http:// www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/sco.htm).88

Responsiveness

Responsiveness refers to an individual who “considers other’s feelings, listens to what others have to say, and recognizes the needs of others.”89 If you filled out the Sociocommunicative Orientation Scale, you would find that the words associated with responsiveness include the following: helpful, responsive to others, sympathetic, compassionate, sensitive to the needs of others, sincere, gentle, warm, tender, and friendly.

Assertiveness

Assertiveness refers to individuals who “can initiate, maintain, and terminate conversations, according to their interpersonal goals.” 90 If you filled out the Sociocommunicative Orientation Scale, you would find that the words associated with assertiveness include the following: defends own beliefs, independent, forceful, has a strong personality, assertive, dominant, willing to take a stand, acts as a leader, aggressive, and competitive.

Versatility

Communication always exists within specific contexts, so picking a single best style to communicate in every context simply can’t be done because not all patterns of communication are appropriate or effective in all situations. As such, McCroskey and Richmond added a third dimension to the mix that they called versatility. 91 In essence, individuals who are competent communicators know when it is both appropriate and effective to use both responsiveness and assertiveness. The notion of pairing the two terms against each other did not make sense to McCroskey and Richmond because both were so important. Other terms scholars have associated with versatility include “adaptability, flexibility, rhetorical sensitivity, and style flexing.” 92The opposite of versatility was also noted by McCroskey and Richmond, who saw such terms as dogmatic, rigid, uncompromising, and unyielding as demonstrating the lack of versatility.

Sociocommunicative Orientation and Interpersonal Communication

Sociocommunicative orientation has been examined in several studies that relate to interpersonal communication. In a study conducted by Brian Patterson and Shawn Beckett, the researchers sought to see the importance of sociocommunicative orientation and how people repair relationships.93 Highly assertive individuals were found to take control of repair situations. Highly responsive individuals, on the other hand, tended to differ in their approaches to relational repair, depending on whether the target was perceived as assertive or responsive. When a target was perceived as highly assertive, the responsive individual tended to let the assertive person take control of the relational repair process. When a target was perceived as highly responsive, the responsive individual was more likely to encourage the other person to self-disclose and took on the role of the listener. As a whole, highly assertive individuals were more likely to stress the optimism of the relationship, while highly responsive individuals were more likely to take on the role of a listener during the relational repair. Later in this book, we will revisit several different interpersonal communication contexts where sociocommunicative orientation has been researched.

Relational Dispositions

The final three dimensions proposed by John Daly were relational dispositions.94 Relational dispositions are general patterns of mental processes that impact how people view and organize themselves in relationships. For our purposes, we’ll examine two unique relational dispositions: attachment and rejection sensitivity.

Attachment

In a set of three different volumes, John Bowlby theorized that humans were born with a set of inherent behaviors designed to allow proximity with supportive others.95These behaviors were called attachment behaviors, and the supportive others were called attachment figures. Inherent in Bowlby’s model of attachment is that humans have a biological drive to attach themselves with others. For example, a baby’s crying and searching help the baby find their attachment figure (typically a parent/guardian) who can provide care, protection, and support. Infants (and adults) view attachment as an issue of whether an attachment figure is nearby, accessible, and attentive? Bowlby believed that these interpersonal models, which were developed in infancy through thousands of interactions with an attachment figure, would influence an individual’s interpersonal relationships across their entire life span. According to Bowlby, the basic internal working model of affection consists of three components.96 Infants who bond with their attachment figure during the first two years develop a model that people are trustworthy, develop a model that informs the infant that he or she is valuable, and develop a model that informs the infant that he or she is effective during interpersonal interactions. As you can easily see, not developing this model during infancy leads to several problems.

If there is a breakdown in an individual’s relationship with their attachment figure (primarily one’s mother), then the infant would suffer long-term negative consequences. Bowlby called his ideas on the importance of mother-child attachment and the lack thereof as the Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis. Bowlby hypothesized that maternal deprivation occurred as a result of separation from or loss of one’s mother or a mother’s inability to develop an attachment with her infant. This attachment is crucial during the first two years of a child’s life. Bowlby predicted that children who were deprived of attachment (or had a sporadic attachment) would later exhibit delinquency, reduced intelligence, increased aggression, depression, and affectionless psychopathy – the inability to show affection or care about others.

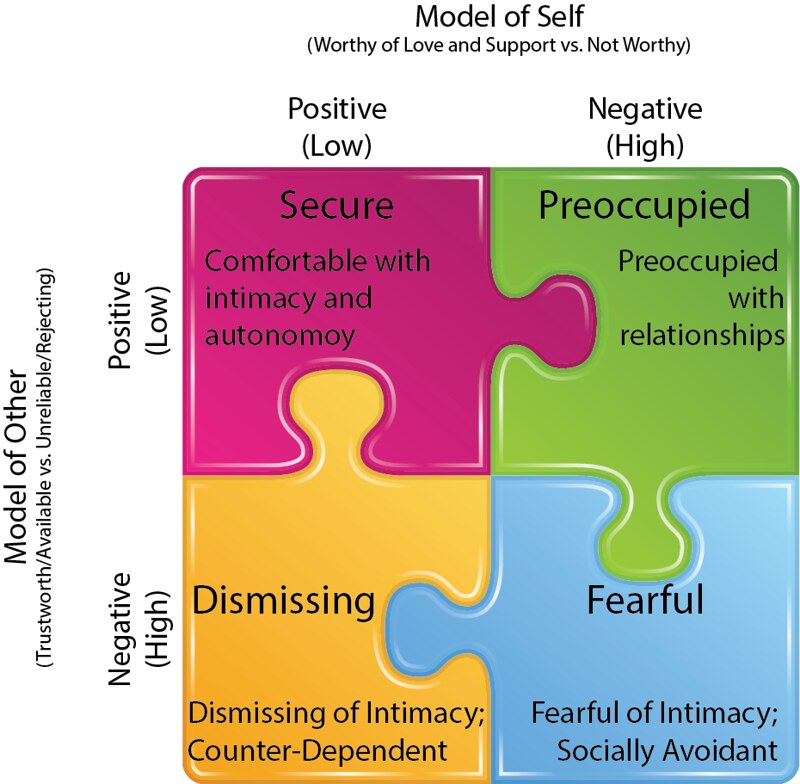

In 1991, Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz expanded on Bowlby’s work developing a scheme for understanding adult attachment.97 In this study, Bartholomew and Horowitz proposed a model for understanding adult attachment. On one end of the spectrum, you have an individual’s abstract image of themself as being either worthy of love and support or not. On the other end of the spectrum, you have an individual’s perception of whether or not another person will be trustworthy/available or another person is unreliable and rejecting. When you combine these dichotomies, you end up with four distinct attachment styles (as seen in Figure 3.3.1).

The first attachment style is labeled “secure,” because these individuals believe that they are loveable and expect that others will generally behave in accepting and responsive ways within interpersonal interactions. Not surprisingly, secure individuals tend to show the most satisfaction, commitment, and trust in their relationships. The second attachment style, preoccupied, occurs when someone does not perceive themself as worthy of love but does generally see people as trustworthy and available for interpersonal relationships. These individuals would attempt to get others to accept them. The third attachment style, fearful (sometimes referred to as fearful avoidants98), represents individuals who see themselves as unworthy of love and generally believe that others will react negatively through either deception or rejection. These individuals simply avoid interpersonal relationships to avoid being rejected by others. Even in communication, fearful people may avoid communication because they simply believe that others will not provide helpful information or others will simply reject their communicative attempts. The final attachment style, dismissing, reflects those individuals who see themselves as worthy of love, but generally believes that others will be deceptive and reject them in interpersonal relationships. These people tend to avoid interpersonal relationships to protect themselves against disappointment that occurs from placing too much trust in another person or making one’s self vulnerable to rejection.

Rejection Sensitivity

Although no one likes to be rejected by other people in interpersonal interactions, most of us do differ from one another in how this rejection affects us as humans. We’ve all had our relational approaches (either by potential friends or dating partners) rejected at some point and know that it kind of sucks to be rejected. The idea that people differ in terms of degree in how sensitive they are to rejection was first discussed in the 1930s by a German psychoanalyst named Karen Horney.99 Rejection sensitivity can be defined as the degree to which an individual expects to be rejected, readily perceives rejection when occurring, and experiences an intensely adverse reaction to that rejection.

First, people that are highly sensitive to rejection expect that others will reject them. This expectation of rejection is generally based on a multitude of previous experiences where the individual has faced real rejection. Hence, they just assume that others will reject them.

Second, people highly sensitive to rejection are more adept at noting when they are being rejected; however, it’s not uncommon for these individuals to see rejection when it does not exist. Horney explains perceptions of rejection in this fashion:

It is difficult to describe the degree of their sensitivity to rejection. Change in an appointment, having to wait, failure to receive an immediate response, disagreement with their opinions, any noncompliance with their wishes, in short, any failure to fulfill their demands on their terms, is felt as a rebuff. And a rebuff not only throws them back on their basic anxiety, but it is also considered equivalent to humiliation. 100

As we can see from this short description from Horney, rejection sensitivity can occur from even the slightest perceptions of being rejected.

Lastly, individuals who are highly sensitive to rejection tend to react negatively when they feel they are being rejected. This negative reaction can be as simple as just not bothering to engage in future interactions or even physical or verbal aggression. The link between the rejection and the negative reaction may not even be completely understandable to the individual. Horney explains, “More often the connection between feeling rebuffed and feeling irritated remains unconscious. This happens all the more easily since the rebuff may have been so slight as to escape conscious awareness. Then a person will feel irritable, or become spiteful and vindictive or feel fatigued or depressed or have a headache, without the remotest suspicion why.” 101 Ultimately, individuals with high sensitivity to rejection can develop a “why bother” approach to initiating new relationships with others. This fear of rejection eventually becomes a self-induced handicap that prevents these individuals from receiving the affection they desire.

As with most psychological phenomena, this process tends to proceed through a series of stages. Horney explains that individuals suffering from rejection sensitivity tend to undergo an eight-step cycle:

- Fear of being rejected.

- Excessive need for affection (e.g., demands for exclusive and unconditional love).

- When the need is not met, they feel rejected.

- The individual reacts negatively (e.g., with hostility) to the rejection.

- Repressed hostility for fear of losing the affection.

- Unexpressed rage builds up inside.

- Increased fear of rejection.

- Increased need for relational reassurance from a partner.

Of course, as an individual’s need for relational reassurance increases, so does their fear of being rejected, and the perceptions of rejection spiral out of control.

As you may have guessed, there is a strong connection between John Bowlby’s attachment theory102 and Karen Horney’s theory of rejection sensitivity. As you can imagine, rejection sensitivity has several implications for interpersonal communication. In a study conducted by Geraldine Downey, Antonio Freitas, Benjamin Michaelis, and Hala Khouri, the researchers wanted to track high versus low rejection sensitive individuals in relationships and how long those relationships lasted.103 The researchers also had the participants complete the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire created by Geraldine Downey and Scott Feldman.104 The study started by having couples keep diaries for four weeks, which helped the researchers develop a baseline perception of an individual’s sensitivity to rejection during the conflict. After the initial four-week period, the researchers revisited the participants one year later to see what had happened. Not surprisingly, high rejection sensitive individuals were more likely to break up during the study than their low rejection sensitivity counterparts.

Key Takeaways

- The idea is that people exist on a continuum from highly extraverted (an individual’s likelihood to be talkative, dynamic, and outgoing) to highly introverted (an individual’s likelihood to be quiet, shy, and more reserved). Generally speaking, highly extraverted individuals tend to have a greater number of interpersonal relationships, but introverted people tend to have more depth in the handful of relationships they have.

- In this chapter, three approach and avoidance traits were discussed: willingness to communicate, shyness, and communication apprehension. Willingness to communicate refers to an individual’s tendency to initiate communicative interactions with other people. Shyness refers to discomfort when an individual is interacting with another person(s) in a social situation. Communication apprehension is the fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons. Where WTC examines initiation of interpersonal interactions, shyness discusses actual reserved interpersonal behavior, and CA is focused on the anxiety experienced (or perceived) in interpersonal interactions.

- Argumentativeness refers to an individual’s tendency to engage in the open exchange of ideas in the form of arguments; whereas, verbal aggressiveness is the tendency to attack an individual’s self-concept instead of an individual’s arguments.

- Sociocommunicative orientation refers to an individual’s combination of both assertive and responsive communication behaviors. Assertive communication behaviors are those that initiate, maintain, and terminate conversations according to their interpersonal goals during interpersonal interactions. Responsive communication behaviors are those that consider others’ feelings, listens to what others have to say, and recognizes the needs of others during interpersonal interactions. Individuals who can appropriately and effectively utilize assertive and responsive behaviors during interpersonal communication across varying contexts are referred to as versatile communicators (or competent communicators).

- John Bowlby’s theory of attachment starts with the basic notion that infants come pre-equipped with a set of behavioral skills that allow them to form attachments with their parents/guardians (specifically their mothers). When these attachments are not formed, the infant will grow up being unable to experience a range of healthy attachments later in life, along with several other counterproductive behaviors.

- Karen Horney’s concept of rejection sensitivity examines the degree to which an individual anxiously expects to be rejected, readily perceives rejection when occurring, and experiences an intensely negative reaction to that rejection. People that have high levels of rejection sensitivity tend to create relational cycles that perpetuate a self-fulfilling prophecy of rejection in their interpersonal relationships.

Exercises

- Fill out the various measures discussed in this section related to communication. After completing these measures, how can your communication traits help explain your interpersonal relationships with others?

- Watch a segment of a political debate on YouTube. Would you characterize debates as argumentative, verbally aggressive, or something else entirely? Why?

- John Bowlby’s attachment theory and Karen Horney’s theory of rejection sensitivity have theoretical overlaps. Do you think that an individual’s early attachment can lead to higher levels of rejection sensitivity? Why or why not?