1.2: Basic Principles of Human Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 115917

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Define and explain the term “communication.”

- Describe the nature of symbols and their importance to human communication.

- Explain seven important factors related to human communication.

The origin of the word communication can be traced back to the Latin word communico, which is translated to mean “to join or unite,” “to connect,” “to participate in” or “to share with all.” This root word is the same one from which we get not only the word communicate, but also common, commune, communion, and community. Thus, we can define communication as a process by which we share ideas or information with other people. We commonly think of communication as talking, but it is much broader than just speech. Other characteristics of voice communicate messages, and we communicate, as well, with eyes, facial expressions, hand gestures, body position, and movement. Let us examine some basic principles about how we communicate with one another.

Communication Is Symbolic

Have you ever noticed that we can hear or look at something like the word “cat” and immediately know what those three letters mean? From the moment you enter grade school, you are taught how to recognize sequences of letters that form words that help us understand the world. With these words, we can create sentences, paragraphs, and books like this one. The letters used to create the word “cat” and then the word itself is what communication scholars call symbols. A symbol is a mark, object, or sign that represents something else by association, resemblance, or convention.

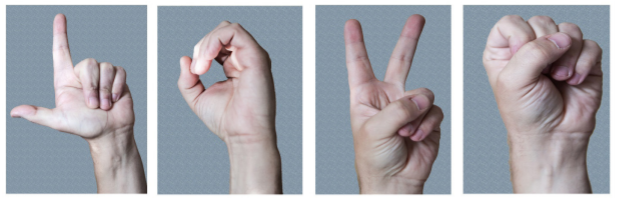

Let’s think about one of the most important words commonly tossed around, love. The four letters that make of the word “l,” “o,” “v,” and “e,” are visual symbols that, when combined, form the word “love,” which is a symbol associated with intense regard or liking. For example, I can “love” chocolate. However, the same four-letter word has other meanings attached to it as well. For example, “love” can represent a deeply intimate relationship or a romantic/sexual attachment. In the first case, we could love our parents/guardians and friends, but in the second case, we experience love as a factor of a deep romantic/sexual relationship. So these are just three associations we have with the same symbol, love. In Figure 1.2.1, we see American Sign Language (ASL) letters for the word “love.” In this case, the hands themselves represent symbols for English letters, which is an agreed upon convention of users of ASL to represent “love.”

Symbols can also be visual representations of ideas and concepts. For example, look at the symbols in Figure 1.2.2 of various social media icons. In this image, you see symbols for a range of different social media sites, including Facebook (lowercase “f”), Twitter (the bird), Snap Chat (the ghost image), and many others. Admittedly, the icon for YouTube uses its name.

The Symbol is Not the Thing

Now that we’ve explained what symbols are, we should probably offer a few very important guides. First, the symbol is not the thing that it is representing. For example, the word “dog” is not a member of the canine family that greets you when you come home every night. If we look back at those symbols listed in Figure 1.2.1, those symbols are not the organizations themselves. The “p” with a circle around it is not Pinterest. The actual thing that is “Pinterest” is a series of computer code that exists on the World Wide Web that allows us, people, to interact.

Arbitrariness of Symbols

How we assign symbols is entirely arbitrary. For example, in Figure 1.2.3, we see two animals that are categorized under the symbols “dog” and “cat.” In this image, the “dog” is on the left side, and the “cat” is on the right side. The words we associate with these animals only exist because we have said it’s so for many, many years. Back when humans were labeling these animals, we could just have easily called the one on the left “cat” and the one on the right “dog,” but we didn’t. If we called the animal on the left “cat,” would that change the nature of what that animal is? Not really. The only thing that would change is the symbol we have associated with that animal.

Let’s look at another symbolic example you are probably familiar with – :). The “smiley” face or the two pieces of punctuation (colon followed by closed parentheses) is probably the most notable symbol used in Internet communication. This symbol may seem like it’s everywhere today, but it’s only existed since September 1982. In early September 1982, a joke was posted on an electronic bulletin board about a fake chemical spill at Carnegie Mellon University. At the time, there was no easy way to distinguish between serious versus non-serious information. A computer scientist named Scott E. Fahlman entered the debate with the following message:

The Original Emoticons

I propose that [sic] the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably more economical to mark things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use:

:-(

Thus the first emoticon, a sequence of keyboard characters used to represent facial expressions or emotions, was born. Even the universal symbol for happiness, the yellow circle with the smiling face, had only existed since 1963 when graphic artist Harvey Ross Ball created it. The happy face was created as a way to raise employee morale at State Mutual Life Assurance Company of Worcester, Massachusetts. Of course, when you merge the happy face with emoticons, we eventually ended up with emojis (Figure 1.2.4). Of course, many people today just take emojis for granted without ever knowing their origin at all.

Communication Is Shared Meaning

Hopefully, in our previous discussion about symbols, you noticed that although the assignment of symbols to real things and ideas is arbitrary, our understanding of them exists because we agree to their meaning. If we were talking and I said, “it’s time for tea,” you may think that I’m going to put on some boiling water and pull out the oolong tea. However, if I said, “it’s time for tea” in the United Kingdom, you would assume that we were getting ready for our evening meal. Same word, but two very different meanings depending on the culture within which one uses the term. In the United Kingdom, high tea (or meat tea) is the evening meal. Dinner, on the other hand, would represent the large meal of the day, which is usually eaten in the middle of the day. Of course, in the United States, we refer to the middle of the day meal as lunch and often refer to the evening meal as dinner (or supper).

Let’s imagine that you were recently at a party. Two of your friends had recently attended the same Broadway play together. You ask them “how the play was,” and here’s how the first friend responded:

So, we got to the theatre 20 minutes early to ensure we were able to get comfortable and could do some people watching before the show started. The person sitting in front of us had the worst comb-over I had ever seen. Halfway through Act 1, the hair was flopping back in our laps like the legs of a spider. I mean, those strands of hair had to be 8 to 9 inches long and came down on us like it was pleading with us to rescue it. Oh, and this one woman who was sitting to our right was wearing this huge fur hat-turban thing on her head. It looked like some kind of furry animal crawled up on her head and died. I felt horrible for the poor guy that was sitting behind her because I’m sure he couldn’t see anything over or around that thing.

Here’s is how your second friend described the experience:

I thought the play was good enough. It had some guy from the UK who tried to have a Brooklyn accent that came in and out. The set was pretty cool though. At one point, the set turned from a boring looking office building into a giant tree. That was pretty darn cool. As for the overall story, it was good, I guess. The show just wasn’t something I would normally see.

In this case, you have the same experience described by two different people. We are only talking about the experience each person had in an abstract sense. In both cases, you had friends reporting on the same experience but from their perceptions of the experience. With your first friend, you learn more about what was going on around your friend in the theatre but not about the show itself. The second friend provided you with more details about her perception of the play, the acting, the scenery, and the story. Did we learn anything about the content of the “play” through either conversation? Not really.

Many of our conversations resemble this type of experience recall. In both cases, we have two individuals who are attempting to share with us through communication specific ideas and meanings. However, sharing meaning is not always very easy. In both cases, you asked your friends, “how the play was.” In the first case, your friend interpreted this phrase as being asked about their experience at the theatre itself. In the second case, your friend interpreted your phrase as being a request for her opinion or critique of the play. As you can see in this example, it’s easy to get very different responses based on how people interpret what you are asking.

Communication scholars often say that “meanings aren’t in words, they’re in people” because of this issue related to interpretation. Yes, there are dictionary definitions of words. Earlier in this chapter, we provided three different dictionary-type definitions for the word “love:” 1) intense regard or liking, 2) a deeply intimate relationship, or 3) a romantic/sexual attachment. These types of definitions we often call denotative definitions. However, it’s important to understand that in addition to denotative definitions, there are also connotative definitions, or the emotions or associations a person makes when exposed to a symbol. For example, how one personally understands or experiences the word “love” is connotative. The warm feeling you get, the memories of experiencing love, all come together to give you a general, personalized understanding of the word itself. One of the biggest problems that occur is when one person’s denotative meaning conflicts with another person’s connotative meaning. For example, when I write the word “dog,” many of you think of four-legged furry family members. If you’ve never been a dog owner, you may just generally think about these animals as members of the canine family. If, however, you’ve had a bad experience with a dog in the past, you may have very negative feelings that could lead you to feel anxious or experience dread when you hear the word “dog.” As another example, think about clowns. Some people see clowns as cheery characters associated with the circus and birthday parties. Other people are genuinely terrified by clowns. Both the dog and clown cases illustrate how we can have symbols that have different meanings to different people.

Communication Involves Intentionality

One area that often involves a bit of controversy in the field of communication is what is called intentionality. Intentionality asks whether an individual purposefully intends to interact with another person and attempt shared meaning. Each time you communicate with others, there is intentionality involved. You may want to offer your opinions or thoughts on a certain topic. However, intentionality is an important concept in communication. Think about times where you might have talked aloud without realizing another person could hear you. Communication can occur at any time. When there is intent among the parties to converse with each other, then it makes the communication more effective.

Others argue that you “cannot, not communicate.” This idea notes that we are always communicating with those around us. As we’ll talk more about later in this book, communication can be both verbal (the words we speak) and nonverbal (gestures, use of space, facial expressions, how we say words, etc.). From this perspective, our bodies are always in a state of nonverbal communication, whether it’s intended or not. Maybe you’ve walked past someone’s office and saw them hunched over at their desk, staring at a computer screen. Based on the posture of the other person, you decide not to say “hi” because the person looks like they are deep in thought and probably busy. In this case, we interpret the person’s nonverbal communication as saying, “I’m busy.” In reality, that person could just as easily be looking at Facebook and killing time until someone drops by and says, “hi.”

Dimensions of Communication

When we communicate with other people, we must always remember that our communication is interpreted at multiple levels. Two common dimensions used to ascertain meaning during communication are relational and content

Relational Dimension

Every time we communicate with others, there is a relational dimension. You can communicate in a tone of friendship, love, hatred, and so forth. This is indicated in how you communicate with your receiver. Think about the phrase, “You are crazy!” It means different things depending on the source of the message. For instance, if your boss said it, you might take it harsher than if your close friend said it to you. You are more likely to receive a message more accurately when you can define the type of relationship that you have with this person. Hence, your relationship with the person determines how you are more likely to interpret the message. Take another example of the words “I want to see you now!” These same words might mean different things if it comes from your boss or if it comes from your lover. You will know that if your boss wants to see you, then it is probably an urgent matter that needs your immediate attention. However, if your lover said it, then you might think that they miss you and can’t bear the thought of being without you for too long.

Content Dimension

In the same fashion, every time we speak, we have a content dimension. The content dimension is the information that is stated explicitly in the message. When people focus on the content of a message, then ignore the relationship dimension. They are focused on the specific words that were used to convey the message. For instance, if you ran into an ex-lover who said “I’m happy for you” about your new relationship. You might wonder what that phrase means. Did it mean that your ex was truly happy for you, or that they were happy to see you in a new relationship, or that your ex thinks that you are happy? One will ponder many interpretations of the message, especially if a relationship is not truly defined.

Another example might be a new acquaintance who talks about how your appearance looks “interesting.” You might be wondering if your new friend is sarcastic, or if they just didn’t know a nicer way of expressing their opinion. Because your relationship is so new, you might think about why they decided to pick that term over another term. Hence, the content of a message impacts how it is received.

Communication Is a Process

The word “process” refers to the idea that something is ongoing, dynamic, and changing with a purpose or towards some end. A communication scholar named David K. Berlo was the first to discuss human communication as a process back in 1960.11 We’ll examine Berlo’s ideas in more detail in Chapter 2, but for now, it’s important to understand the basic concept of communication as a process. From Berlo’s perspective, communication is a series of ongoing interactions that change over time. For example, think about the number of “inside jokes” you may have with your best friend. Sometimes you can get to the point where all you say is one word, and both of you can crack up laughing. This level of familiarity and short-hand communication didn’t exist when you first met but has developed over time. Ultimately, the more interaction you have with someone, the more your relationship with that person will evolve.

Communication Is Culturally Determined

The word culture refers to a “group of people who through a process of learning can share perceptions of the world that influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.”12 Let’s breakdown this definition. First, it’s essential to recognize that culture is something we learn. From the moment we are born, we start to learn about our culture. We learn culture from our families, our schools, our peers, and many other sources as we age. Specifically, we learn perceptions of the world. We learn about morality. We learn about our relationship with our surroundings. We learn about our places in a greater society. These perceptions ultimately influence what we believe, what we value, what we consider “normal,” and what rules we live by. For example, many of us have beliefs, values, norms, and rules that are directly related to the religion in which we were raised. As an institution, religion is often one of the dominant factors of culture around the world.

Let’s start by looking at how religion can impact beliefs. Your faith can impact what you believe about the nature of life and death. For some, depending on how you live, you’ll either go to a happy place (Heaven, Nirvana, Elysium, etc.) or a negative place (Hell, Samsara, Tartarus, etc.). We should mention that Samsara is less a “place” and more the process of reincarnation as well as one’s actions and consequences from the past, present, and future.

Religion can also impact what you value. Cherokee are taught to value the earth and the importance of keep balance with the earth. Judaic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam, etc.), on the other hand, teach that humans have been placed on earth to dominate and control the earth. As such, the value is more on what the earth can provide than on ensuring harmony with nature.

Religion can also impact what you view as “normal.” Many adherents to Islam stress the importance of female modesty, so it is normal for women to cover their heads when in public or completely cover their entire bodies from head to toe. On the other hand, one branch of Raëlianism promotes a pro-sex feminist stance where nudity and sex work are normal and even celebrated.

Different religions have different rules that get created and handed down. For most Western readers, the most famous set of rules is probably the Judaic Tradition’s Ten Commandments. Conversely, Hindus have a text of religious laws transmitted in the Vedas. Most major religions have, at some point or another, had religious texts that became enshrined laws within those societies.

Finally, these beliefs, values, norms, and rules ultimately impact how all of us interact and behave with others. For example, because of the Islamic rules on and norms about female modesty, in many Islamic countries, women cannot speak with men unless they are directly related to them by birth or marriage. The critical part to remember about these actual behaviors is that we often have no idea how (and to what degree) our culture influences our communicative behavior until we are interacting with someone from a culture that differs from ours. We’ll talk more about issues of intercultural interpersonal interactions later in this text.

Communication Occurs in a Context

Another factor that influences how we understand others is the context, the circumstance, environment, setting, and/or situation surrounding an interaction. Most people learning about context are generally exposed during elementary school when you are trying to figure out the meaning of a specific word. You may have seen a complicated word and been told to use “context clues” to understand what the word means. In the same vein, when we analyze how people are communicating, we must understand the context of that communication.

Imagine you’re hanging out at your local restaurant, and you hear someone at the next table say, “I can’t believe that guy. He’s always out in left field!” As an American idiom, we know that “out in left field” generally refers to something unexpected or unusual. The term stems out of baseball because the player who hangs out in left field has the farthest to throw to get a baseball back to the first baseman in an attempt to tag out a runner. However, if you were listening to this conversation in farmland, you could be hearing someone describe a specific geographic location (e.g., “He was out in left field chasing after a goat who stumbled that way”). In this case, context does matter.

Communication Is Purposeful

We communicate for different reasons. We communicate in an attempt to persuade people. We communicate to get people to like us. We communicate to express our liking of other people. We could list different reasons why we communicate with other people. Often we may not even be aware of the specific reason or need we have for communicating with others. We’ll examine more of the different needs that communication fulfills along with the motives we often have for communicating with others in Chapter 2.

Key Takeaways

- Communication is derived from the Latin root communico, which means to share. As communicators, each time we talk to others, we share part of ourselves.

- Symbols are words, pictures, or objects that we use to represent something else. Symbols convey meanings. They can be written, spoken, or unspoken.

- There are many aspects to communication. Communication involves shared meaning; communication is a process; has a relationship, intent, & content dimension; is culturally determined, occurs in context; and is purposeful.

Exercises

- In groups, provide a real-life example for each of these aspects: Communication involves shared meaning, communication is a process, has a relationship, intent, & content dimension, occurs in a context, is purposeful, and is culturally defined.

- As a class, come up with different words. Then, divide the class and randomly distribute the words. Each group will try to get the other group to guess their words either by drawing symbols or displaying nonverbal behaviors. Then discuss how symbols impact perception and language.

- Can you think of some examples of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis? For instance, in Japan, the word “backyard” does not exist. Because space is so limited, most Japanese people do not have backyards. This term is foreign to them, but in America, most of our houses have a backyard.