7.3: Listening

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 115955

- Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter & Katherine S. Thweatt

- SUNY New Paltz & SUNY Oswego via OpenSUNY

Learning Outcomes

- Differentiate between hearing and listening.

- Understand how to listen effectively.

- Recognize the different types of listening.

When it comes to daily communication, we spend about 45% of our listening, 30% speaking, 16% reading, and 9% writing.36 However, most people are not entirely sure what the word “listening” is or how to do it effectively.

Hearing Is Not Listening

Hearing refers to a passive activity where an individual perceives sound by detecting vibrations through an ear. Hearing is a physiological process that is continuously happening. We are bombarded by sounds all the time. Unless you are in a sound-proof room or are 100% deaf, we are constantly hearing sounds. Even in a sound-proof room, other sounds that are normally not heard like a beating heart or breathing will become more apparent as a result of the blocked background noise.

Listening, on the other hand, is generally seen as an active process. Listening is “focused, concentrated attention for the purpose of understanding the meanings expressed by a [source].”37 From this perspective, hearing is more of an automatic response when your ear perceives information; whereas, listening is what happens when we purposefully attend to different messages.

We can even take this a step further and differentiate normal listening from critical listening. Critical listening is the “careful, systematic thinking and reasoning to see whether a message makes sense in light of factual evidence.”38 From this perspective, it’s one thing to attend to someone’s message, but something very different to analyze what the person is saying based on known facts and evidence.

Let’s apply these ideas to a typical interpersonal situation. Let’s say that you and your best friend are having dinner at a crowded restaurant. Your ear is going to be attending to a lot of different messages all the time in that environment, but most of those messages get filtered out as “background noise,” or information we don’t listen to at all. Maybe then your favorite song comes on the speaker system the restaurant is playing, and you and your best friend both attend to the song because you both like it. A minute earlier, another song could have been playing, but you tuned it out (hearing) instead of taking a moment to enjoy and attend to the song itself (listen). Next, let’s say you and your friend get into a discussion about the issues of campus parking. Your friend states, “There’s never any parking on campus. What gives?” Now, if you’re critically listening to what your friend says, you’ll question the basis of this argument. For example, the word “never” in this statement is problematic because it would mean that the campus has zero available parking, which is probably not the case. Now, it may be difficult for your friend to find a parking spot on campus, but that doesn’t mean that there’s “never any parking.” In this case, you’ve gone from just listening to critically evaluating the argument your friend is making.

Model of Listening

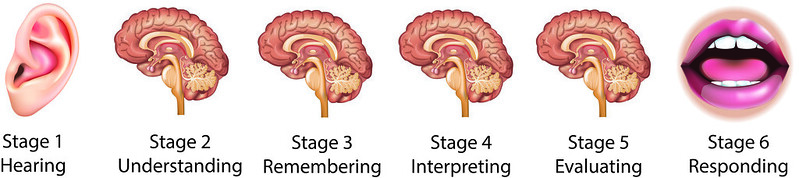

Judi Brownell created one of the most commonly used models for listening.39 Although not the only model of listening that exists, we like this model because it breaks the process of hearing down into clearly differentiated stages: hearing, understanding, remembering, interpreting, evaluating, and responding (Figure 7.3.1).

Hearing

From a fundamental perspective, for listening to occur, an individual must attend to some kind of communicated message. Now, one can argue that hearing should not be equated with listening (as we did above), but it is the first step in the model of listening. Simply, if we don’t attend to the message at all, then communication never occurred from the receiver’s perspective.

Imagine you’re standing in a crowded bar with your friends on a Friday night. You see your friend Darry and yell her name. In that instant, you, as a source of a message, have attempted to send a message. If Darry is too far away, or if the bar is too loud and she doesn’t hear you call her name, then Darry has not engaged in stage one of the listening model. You may have tried to initiate communication, but the receiver, Darry, did not know that you initiated communication.

Now, to engage in mindful listening, it’s important to take hearing seriously because of the issue of intention. If we go into an interaction with another person without really intending to listening to what they have to say, we may end up being a passive listener who does nothing more than hear and nod our heads. Remember, mindful communication starts with the premise that we must think about our intentions and be aware of them.

Understanding

The second stage of the listening model is understanding, or the ability to comprehend or decode the source’s message. When we discussed the basic models of human communication in Chapter 2, we discussed the idea of decoding a message. Simply, decoding is when we attempt to break down the message we’ve heard into comprehensible meanings. For example, imagine someone coming up to you asking if you know, “Tintinnabulation of vacillating pendulums in inverted, metallic resonant cups.” Even if you recognize all of the words, you may not completely comprehend what the person is even trying to say. In this case, you cannot decode the message. Just as an FYI, that means “jingle bells.”

Remembering

Once we’ve decoded a message, we have to actually remember the message itself, or the ability to recall a message that was sent. We are bombarded by messages throughout our day, so it’s completely possible to attend to a message and decode it and then forget it about two seconds later.

For example, I always warn my students that my brain is like a sieve. If you tell me something when I’m leaving the class, I could easily have forgotten what you told me three seconds later because my brain switches gear to what I’m doing next: I run into another student into in the hallway; another thought pops into my head; etc. As such, I always recommend emailing me important things, so I don’t forget them. In this case, it’s not that I don’t understand the message; I just get distracted, and my remembering process fails me. This problem plagues all of us.

Interpreting

The next stage in the HURIER Model of Listening is interpreting. “Interpreting messages involves attention to all of the various speaker and contextual variables that provide a background for accurately perceived messages.”40 So, what do we mean by contextual variables? A lot of the interpreting process is being aware of the nonverbal cues (both oral and physical) that accompany a message to accurately assign meaning to the message.

Imagine you’re having a conversation with one of your peers, and he says, “I love math.” Well, the text itself is demonstrating an overwhelming joy and calculating mathematical problems. However, if the message is accompanied by an eye roll or is said in a manner that makes it sound sarcastic, then the meaning of the oral phrase changes. Part of interpreting a message then is being sensitive to nonverbal cues.

Evaluating

The next stage is the evaluating stage, or judging the message itself. One of the biggest hurdles many people have with listening is the evaluative stage. Our personal biases, values, and beliefs can prevent us from effectively listening to someone else’s message.

Let’s imagine that you despise a specific politician. It’s gotten to the point where if you hear this politician’s voice, you immediately change the television channel. Even hearing other people talk about this politician causes you to tune out completely. In this case, your own bias against this politician prevents you from effectively listening to their message or even others’ messages involving this politician. Overcoming our own biases against the source of a message or the content of a message in an effort to truly listen to a message is not easy. One of the reasons listening is a difficult process is because of our inherent desire to evaluate people and ideas.

When it comes to evaluating another person’s message, it’s important to remember to be mindful. As we discussed in Chapter 1, to be a mindful communicator, you must listen with an open ear that is nonjudging. Too often, we start to evaluate others’ messages with an analytical or cold quality that is antithetical to being mindful.

Responding

In Figure 7.3.1, hearing is represented by an ear, the brain represents the next four stages, and a person’s mouth represents the final stage. It’s important to realize that effective listening starts with the ear and centers in the brain, and only then should someone provide feedback to the message itself. Often, people jump from hearing and understanding to responding, which can cause problems as they jump to conclusions that have arisen by truncated interpretation and evaluation.

Ultimately, how we respond to a source’s message will dictate how the rest of that interaction will progress. If we outright dismiss what someone is saying, we put up a roadblock that says, “I don’t want to hear anything else.” On the other hand, if we nod our heads and say, “tell me more,” then we are encouraging the speaker to continue the interaction. For effective communication to occur, it’s essential to consider how our responses will impact the other person and our relationship with that other person.

Overall, when it comes to being a mindful listener, it’s vital to remember COAL: curiosity, openness, acceptance, and love.41 We need to go into our interactions with others and try to see things from their points of view. When we engage in COAL, we can listen mindfully and be in the moment.

Taxonomy of Listening

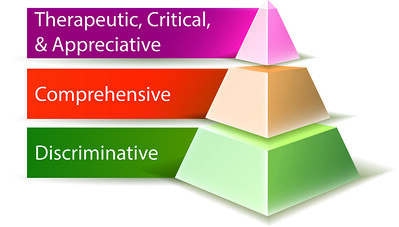

Now that we’ve introduced the basic concepts of listening, let’s examine a simple taxonomy of listening that was created by Andrew Wolvin and Carolyn Coakley.42 The basic premise of the Wolvin and Coakley taxonomy of listening is that there are fundamental parts to listening and then higher-order aspects of listening (Figure 7.3.2). Let’s look at each of these parts separately.

Discriminative

The base level of listening is what Wolvin and Coakley called discriminative listening, or distinguishing between auditory and visual stimuli and determining which to actually pay attention to. In many ways, discriminative listening focuses on how hearing and seeing a wide range of different stimuli can be filtered and used.

We’re constantly bombarded by a variety of messages in our day-to-day lives. We have to discriminate between which messages we want to pay attention to and which ones we won’t. As a metaphor, think of discrimination as your email inbox. Every day you have to filter out messages (aka spam) to find the messages you want to actually read. In the same way, our brains are constantly bombarded by messages, and we have to filter some in and most of them out.

Comprehensive

If we achieve discriminative listening, then we can progress to comprehensive listening. “Comprehensive listening requires the listener to use the discriminative skills while functioning to understand and recall the speaker’s information.”43 If we go back and look at Figure 7.3.1, we can see that comprehensive listening essentially aligns with understanding and remembering.

Wolvin and Coakley argued that discriminative and comprehensive listening are foundational levels of listening. If these foundational levels of listening are met, then they can progress to the other three, higher-order levels of listening: therapeutic, critical, and appreciative.

Therapeutic

Therapeutic listening occurs when an individual is a sounding board for another person during an interaction. For example, your best friend just fought with their significant other and they’ve come to you to talk through the situation.

Critical

The next aspect of listening is critical listening, or really analyzing the message that is being sent. Instead of just being a passive receiver of information, the essential goal of listening is to determine the acceptability or validity of the message(s) someone is sending.

Appreciative

Lastly, we have appreciative listening, which is when someone simply enjoys the act of listening or the message being sent. For example, let’s say you’re watching a Broadway musical or play or even a new movie at the cinema. While you may be engaged critically, you also may be simply appreciative and enjoying the act of listening to the message.

Listening Styles

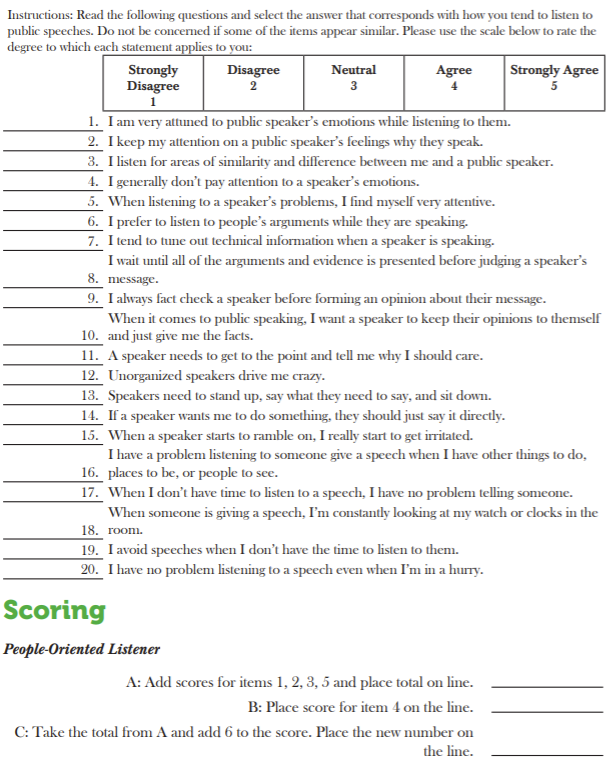

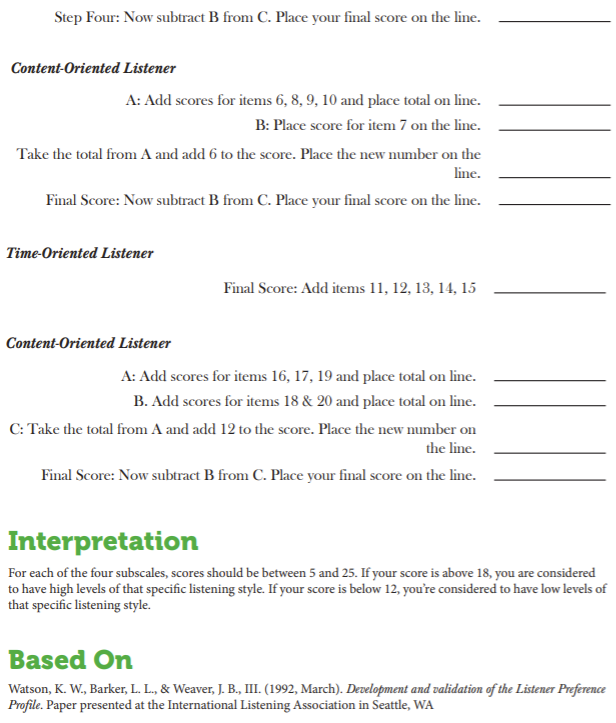

Now that we have a better understanding of how listening works, let’s talk about four different styles of listening researchers have identified. Kittie Watson, Larry Barker, and James Weaver defined listening styles as “attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions about the how, where, when, who, and what of the information reception and encoding process.”44 Watson et al. identified four distinct listening styles: people, content, action, and time. Before progressing to learning about the different listening styles, take a minute to complete the measure in Table 7.3.1, The Listening Style Questionnaire. The Listening Style Questionnaire is based on the original work of Watson, Barker, and Weaver.45

|

The Four Listening Styles

People

The first listening style is the people-oriented listening style. People-oriented listeners tend to be more focused on the person sending the message than the content of the message. As such, people-oriented listeners focus on the emotional states of senders of information. One way to think about people-oriented listeners is to see them as highly compassionate, empathic, and sensitive, which allows them to put themselves in the shoes of the person sending the message.

People-oriented listeners often work well in helping professions where listening to the person and understanding their feelings is very important (e.g., therapist, counselor, social worker). People-oriented listeners are also very focused on maintaining relationships, so they are good at casual conservation where they can focus on the person.

Action

The second listening style is the action-oriented listener. Action-oriented listeners are focused on what the source wants. The action-oriented listener wants a source to get to the point quickly. Instead of long, drawn-out lectures, the action-oriented speaker would prefer quick bullet points that get to what the source desires. Action-oriented listeners “tend to preference speakers that construct organized, direct, and logical presentations.”46

When dealing with an action-oriented listener, it’s important to realize that they want you to be logical and get to the point. One of the things action-oriented listeners commonly do is search for errors and inconsistencies in someone’s message, so it’s important to be organized and have your facts straight.

Content

The third type of listener is the content-oriented listener, or a listener who focuses on the content of the message and process that message in a systematic way. Of the four different listening styles, content-oriented listeners are more adept at listening to complex information. Content-oriented listeners “believe it is important to listen fully to a speaker’s message prior to forming an opinion about it (while action listeners tend to become frustrated if the speaker is ‘wasting time’).”47

When it comes to analyzing messages, content-oriented listeners really want to dig into the message itself. They want as much information as possible in order to make the best evaluation of the message. As such, “they want to look at the time, the place, the people, the who, the what, the where, the when, the how … all of that. They don’t want to leave anything out.”48

Time

The final listening style is the time-oriented listening style. Time-oriented listeners are sometimes referred to as “clock watchers” because they’re always in a hurry and want a source of a message to speed things up a bit. Time-oriented listeners “tend to verbalize the limited amount of time they are willing or able to devote to listening and are likely to interrupt others and openly signal disinterest.”49

They often feel that they are overwhelmed by so many different tasks that need to be completed (whether real or not), so they usually try to accomplish multiple tasks while they are listening to a source. Of course, multitasking often leads to someone’s attention being divided, and information being missed.

Thinking About the Four Listening Types

Kina Mallard broke down the four listening styles and examined some of the common positive characteristics, negative characteristics, and strategies for communicating with the different listening styles (Table 7.3.2).50

| People-Oriented Listener | ||

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Show care and concern for others | Over involved in feelings of others | Use stories and illustrations to make points |

| Are nonjudgmental | Avoid seeing faults in others | Use “we” rather than “I” in conversations |

| Provide clear verbal and nonverbal feedback signals | Internalize/adopt emotional states of others | Use emotional examples and appeals |

| Are interested in building relationships | Are overly expressive when giving feedback | Show some vulnerability when possible |

| Notice others’ moods quickly | Are nondiscriminating in building relationships | Use self-effacing humor or illustrations |

| Action-Oriented Listeners | ||

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Get to the point quickly | Tend to be impatient with rambling speakers | Keep main points to three or fewer |

| Give clear feedback concerning expectations | Jump ahead and reach conclusions quickly | Keep presentations short and concise |

| Concentrate on understanding task | Jump ahead or finishes thoughts of speakers | Have a step-by-step plan and label each step |

| Action-Oriented Listeners | ||

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Help others focus on what’s important | Minimize relationship issues and concerns | Watch for cues of disinterest and pick up vocal pace at those points or change subjects |

| Encourage others to be organized and concise | Ask blunt questions and appear overly critical | Speak at a rapid but controlled rate |

| Content-Oriented Listeners | ||

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Value technical information | Are overly detail oriented | Use two-side arguments when possible |

| Test for clarity and understanding | May intimidate others by asking pointed questions | Provide hard data when available |

| Encourage others to provide support for their ideas | Minimize the value of nontechnical information | Quote credible experts |

| Welcome complex and challenging information | Discount information from nonexperts | Suggest logical sequences and plan |

| Look at all sides of an issue | Take a long time to make decisions | Use charts and graphs |

| Time-Oriented Listeners | ||

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Manage and save time | Tend to be impatient with time wasters | Ask how much time the person has to listen |

| Set time guidelines for meeting and conversations | Interrupt others | Try to go under time limits when possible |

| Let others know listening-time requirements | Let time affect their ability to concentrate | Be ready to cut out necessary examples and information |

| Discourage wordy speakers | Rush speakers by frequently looking at watches/clock | Be sensitive to nonverbal cues indicating impatience or a desire to leave |

| Time-Oriented Listeners | ||

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Give cues to others when time is being wasted | Limit creativity in others by imposing time pressures | Get to the bottom line quickly |

| Original Source: Mallard, K. S. (1999). Lending an ear: The chair’s role as listener. The Department Chair, 9(3), 1-13. | ||

Hopefully, this section has helped you further understand the complexity of listening. We should mention that many people are not just one listening style or another. It’s possible to be a combination of different listening styles. However, some of the listening style combinations are more common. For example, someone who is action-oriented and time-oriented will want the bare-bones information so they can make a decision. On the other hand, it’s hard to be a people-oriented listener and time-oriented listener because being empathic and attending to someone’s feelings takes time and effort.

Mindfulness Activity

One of the hardest skills to master when it comes to mindfulness is mindful listening. To engage in mindful listening, Elaine Smookler recommends using the HEAR method:

- HALT — Halt whatever you are doing and offer your full attention.

- ENJOY — Enjoy a breath as you choose to receive whatever is being communicated to you—wanted or unwanted.

- ASK — Ask yourself if you really know what they mean, and if you don’t, ask for clarification. Instead of making assumptions, bring openness and curiosity to the interaction. You might be surprised at what you discover.

- REFLECT — Reflect back to them what you heard. This tells them that you were really listening.51

For this mindfulness activity, we want you to engage in mindful listening. Start by having a conversation with a friend, romantic partner, or family member. Before beginning the conversation, find a location that has minimal distractions, so try not to engage in this activity in a public space. Also, turn off the television and radio. The goal is to focus your attention on the other person. Start by employing the HEAR method for listening during your conversation. After you have finished this conversation, try to answer the following questions:

- How easy was it for you to provide your conversational partner your full attention? When stray thoughts entered your head, how did you refocus yourself?

- Were you able to pay attention to your breathing while engaged in this conversation? Were you breathing lightly or heavily? Did your breathing get in the way of you listening mindfully? If yes, what happened?

- Did you attempt to empathize with your conversational partner? How easy was it to understand where they were coming from? Was it still easy to empathize if you didn’t agree with something they said or didn’t like something they said?

- How did your listening style impact your ability to stay mindful while listening? Do you think all four listening styles are suited for mindful listening? Why?

Key Takeaways

- Hearing happens when sound waves hit our eardrums. Listening involves processing these sounds into something meaningful.

- The listening process includes: having the motivation to listen, clearly hearing the message, paying attention, interpreting the message, evaluating the message, remembering and responding appropriately.

- There are many types of listening styles: comprehension, evaluative, empathetic, and appreciative.

Exercises

- Do a few listening activities. Go to: www.medel.com/resources-for-successsoundscape/

- For the next week, do a listening diary. Take notes of all the things you listen to and analyze to see if you are truly a good listener. Do you ask people to repeat things? Do you paraphrase?

- After completing the Listening Styles Questionnaire, think about your own listening style and how it impacts how you interact with others. What should you think about when communicating with people who have a different listening style?