2.1.1: The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 92648

- Mehgan Andrade and Neil Walker

- College of the Canyons

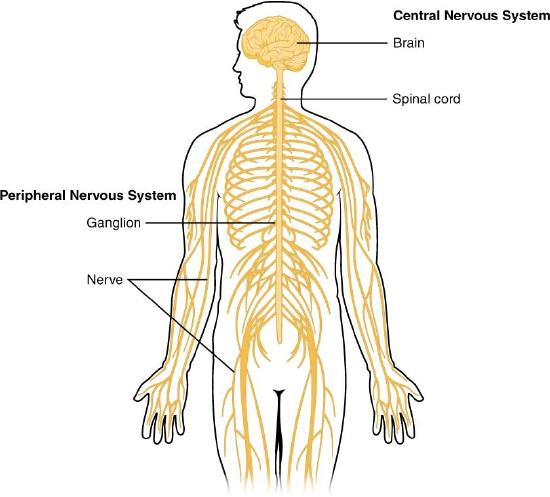

The nervous system can be divided into two major regions: the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) is the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) is everything else (Figure 1). The brain is contained within the cranial cavity of the skull, and the spinal cord is contained within the vertebral cavity of the vertebral column. It is a bit of an oversimplification to say that the CNS is what is inside these two cavities and the peripheral nervous system is outside of them, but that is one way to start to think about it. In actuality, there are some elements of the peripheral nervous system that are within the cranial or vertebral cavities. The peripheral nervous system is so named because it is on the periphery—meaning beyond the brain and spinal cord. Depending on different aspects of the nervous system, the dividing line between central and peripheral is not necessarily universal.

Nervous tissue, present in both the CNS and PNS, contains two basic types of cells: neurons and glial cells. A glial cell is one of a variety of cells that provide a framework of tissue that supports the neurons and their activities. The neuron is the more functionally important of the two, in terms of the communicative function of the nervous system. To describe the functional divisions of the nervous system, it is important to understand the structure of a neuron.

Neurons are cells and therefore have a soma , or cell body, but they also have extensions of the cell; each extension is generally referred to as a process . There is one important process that every neuron has called an axon , which is the fiber that connects a neuron with its target.

Another type of process that branches off from the soma is the dendrite . Dendrites are responsible for receiving most of the input from other neurons.

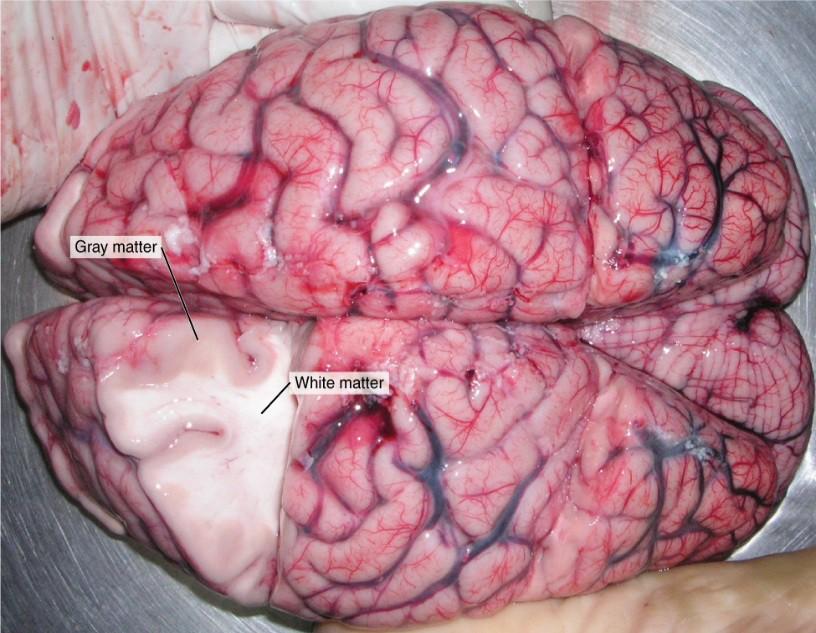

Looking at nervous tissue, there are regions that predominantly contain cell bodies and regions that are largely composed of just axons. These two regions within nervous system structures are often referred to as gray matter (the regions with many cell bodies and dendrites) or white matter (the regions with many axons). Figure 2 demonstrates the appearance of these regions in the brain and spinal cord. The colors ascribed to these regions are what would be seen in “fresh,” or unstained, nervous tissue. Gray matter is not necessarily gray. It can be pinkish because of blood content, or even slightly tan, depending on how long the tissue has been preserved. But white matter is white because axons are insulated by a lipid-rich substance called myelin . Lipids can appear as white (“fatty”) material, much like the fat on a raw piece of chicken or beef. Actually, gray matter may have that color ascribed to it because next to the white matter, it is just darker—hence, gray.

The distinction between gray matter and white matter is most often applied to central nervous tissue, which has large regions that can be seen with the unaided eye. When looking at peripheral structures, often a microscope is used and the tissue is stained with artificial colors. That is not to say that central nervous tissue cannot be stained and viewed under a microscope, but unstained tissue is most likely from the CNS—for example, a frontal section of the brain or cross section of the spinal cord.

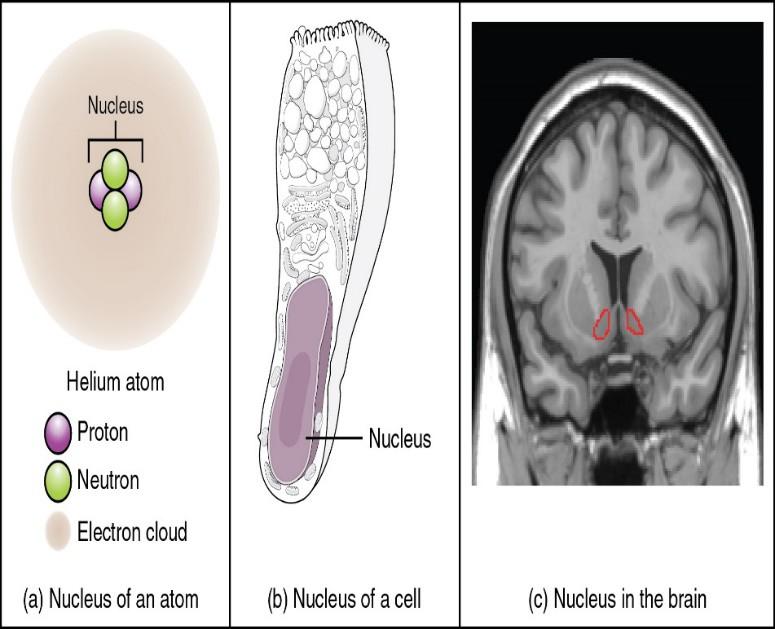

Regardless of the appearance of stained or unstained tissue, the cell bodies of neurons or axons can be located in discrete anatomical structures that need to be named. Those names are specific to whether the structure is central or peripheral. A localized collection of neuron cell bodies in the CNS is referred to as a nucleus . In the PNS, a cluster of neuron cell bodies is referred to as a ganglion . Figure 3 indicates how the term nucleus has a few different meanings within anatomy and physiology. It is the center of an atom, where protons and neutrons are found; it is the center of a cell, where the DNA is found; and it is a center of some function in the CNS. There is also a potentially confusing use of the word ganglion (plural = ganglia) that has a historical explanation. In the central nervous system, there is a group of nuclei that are connected together and were once called the basal ganglia before “ganglion” became accepted as a description for a peripheral structure. Some sources refer to this group of nuclei as the “basal nuclei” to avoid confusion.

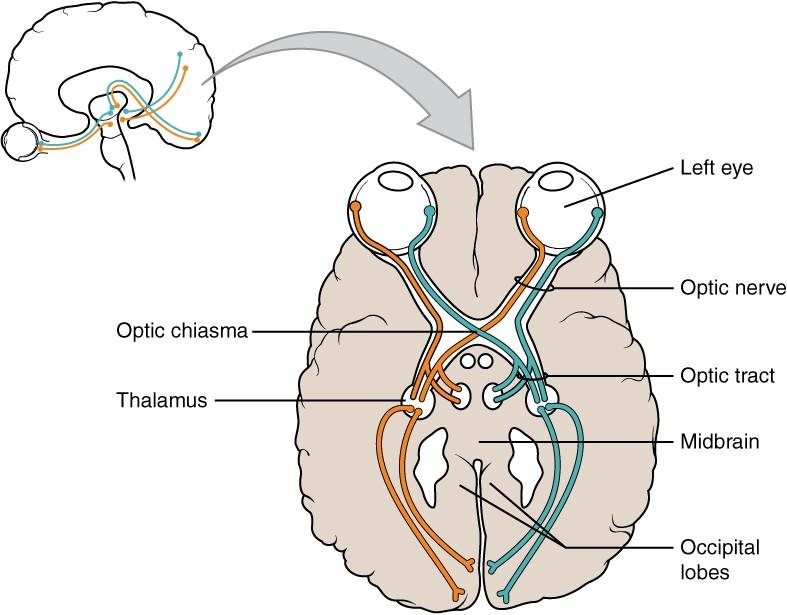

Terminology applied to bundles of axons also differs depending on location. A bundle of axons, or fibers, found in the CNS is called a tract whereas the same thing in the PNS would be called a nerve . There is an important point to make about these terms, which is that they can both be used to refer to the same bundle of axons. When those axons are in the PNS, the term is nerve, but if they are CNS, the term is tract. The most obvious example of this is the axons that project from the retina into the brain. Those axons are called the optic nerve as they leave the eye, but when they are inside the cranium, they are referred to as the optic tract. There is a specific place where the name changes, which is the optic chiasm, but they are still the same axons (Figure 4). A similar situation outside of science can be described for some roads. Imagine a road called “Broad Street” in a town called “Anyville.” The road leaves Anyville and goes to the next town over, called “Hometown.” When the road crosses the line between the two towns and is in Hometown, its name changes to “Main Street.” That is the idea behind the naming of the retinal axons. In the PNS, they are called the optic nerve, and in the CNS, they are the optic tract. Table 1 helps to clarify which of these terms apply to the central or peripheral nervous systems.

How Much of Your Brain Do You Use?

Have you ever heard the claim that humans only use 10 percent of their brains? Maybe you have seen an advertisement on a website saying that there is a secret to unlocking the full potential of your mind—as if there were 90 percent of your brain sitting idle, just waiting for you to use it. If you see an ad like that, don’t click. It isn’t true.

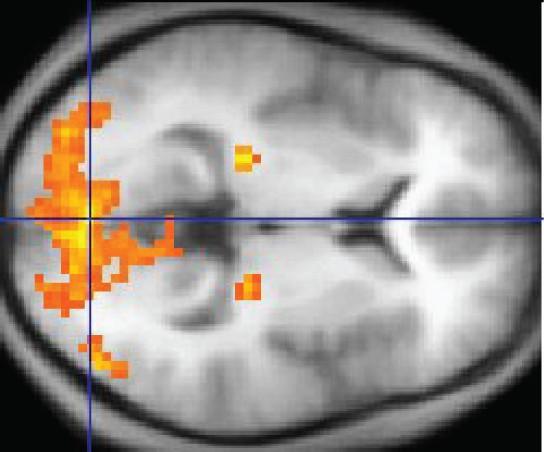

An easy way to see how much of the brain a person uses is to take measurements of brain activity while performing a task. An example of this kind of measurement is functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which generates a map of the most active areas and can be generated and presented in three dimensions (Figure 6). This procedure is different from the standard MRI technique because it is measuring changes in the tissue in time with an experimental condition or event.

The underlying assumption is that active nervous tissue will have greater blood flow. By having the subject perform a visual task, activity all over the brain can be measured. Consider this possible experiment: the subject is told to look at a screen with a black dot in the middle (a fixation point). A photograph of a face is projected on the screen away from the center. The subject has to look at the photograph and decipher what it is. The subject has been instructed

to push a button if the photograph is of someone they recognize. The photograph might be of a celebrity, so the subject would press the button, or it might be of a random person unknown to the subject, so the subject would not press the button.

In this task, visual sensory areas would be active, integrating areas would be active, motor areas responsible for moving the eyes would be active, and motor areas for pressing the button with a finger would be active. Those areas are distributed all around the brain and the fMRI images would show activity in more than just 10 percent of the brain (some evidence suggests that about 80 percent of the brain is using energy—based on blood flow to the tissue—during well- defined tasks similar to the one suggested above). This task does not even include all of the functions the brain performs. There is no language response, the body is mostly lying still in the MRI machine, and it does not consider the autonomic functions that would be ongoing in the background.

|

CNS |

PNS |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Group of Neuron Cell Bodies (i.e., gray matter) |

Nucleus |

Ganglion |

|

Bundle of Axons (i.e., white matter) |

Tract |

Nerve |

Visit the Nobel Prize web site to play an interactive game that demonstrates the use of this technology and compares it with other types of imaging technologies.

In 2003, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Paul C. Lauterbur and Sir Peter Mansfield for discoveries related to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This is a tool to see the structures of the body (not just the nervous system) that depends on magnetic fields associated with certain atomic nuclei. The utility of this technique in the nervous system is that fat tissue and water appear as different shades between black and white. Because white matter is fatty (from myelin) and gray matter is not, they can be easily distinguished in MRI images.

Visit the Nobel Prize web site to play an interactive game that demonstrates the use of this technology and compares it with other types of imaging technologies. Also, the results from an MRI session are compared with images obtained from X-ray or computed tomography. How do the imaging techniques shown in this game indicate the separation of white and gray matter compared with the freshly dissected tissue shown earlier?