1.2: The History of Sociology

- Page ID

- 57030

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \) \( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)\(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)\(\newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

Tradition vs. Science

Key Points

Key Terms

Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

Understanding Culture and Behavior Instead of Predicting

Early Thinkers and Comte

Key Points

Key Terms

Early Social Research and Martineau

Key Points

Key Terms

Harriet Martineau

Translating Comte

Martineau’s Writing

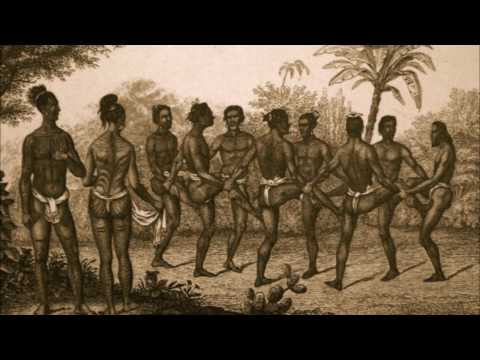

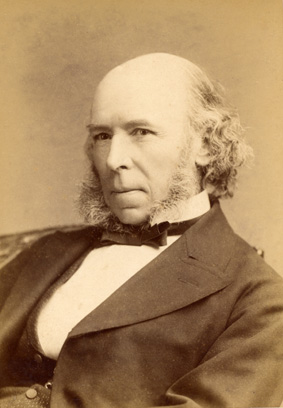

Spencer and Social Darwinism

Key Points

Key Terms

Spencer’s Synthetic Philosophy

Spencer and Progress

Social Darwinism

Criticism

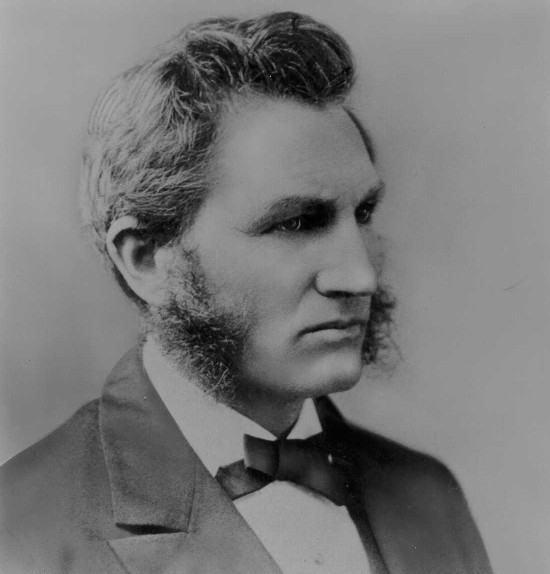

Class Conflict and Marx

Key Points

Key Terms

Means of Production, Relations of Production

Modes of Production

Instabilities in Capitalism

Durkheim and Social Integration

Key Points

Key Terms

Formation of Collective Consciousness

Durkheim and Modernity

Organic versus Mechanical Solidarity

Protestant Work Ethic and Weber

Key Points

Key Terms

Max Weber

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Weber’s Evidence and Argument

The Development of Sociology in the U.S.

Key Points

Key Terms

Works and ideas

“The real object of science is to benefit man. A science which fails to do this, however agreeable its study, is lifeless. Sociology, which of all sciences should benefit man most, is in danger of falling into the class of polite amusements, or dead sciences. It is the object of this work to point out a method by which the breath of life may be breathed into its nostrils. “

Criticism of laissez-faire

Influence on academic sociology

Contributors and Attributions

CC licensed content, Specific attribution