6.6: Social Structure in the Global Perspective

- Page ID

- 57057

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \) \( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)\(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)\(\newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

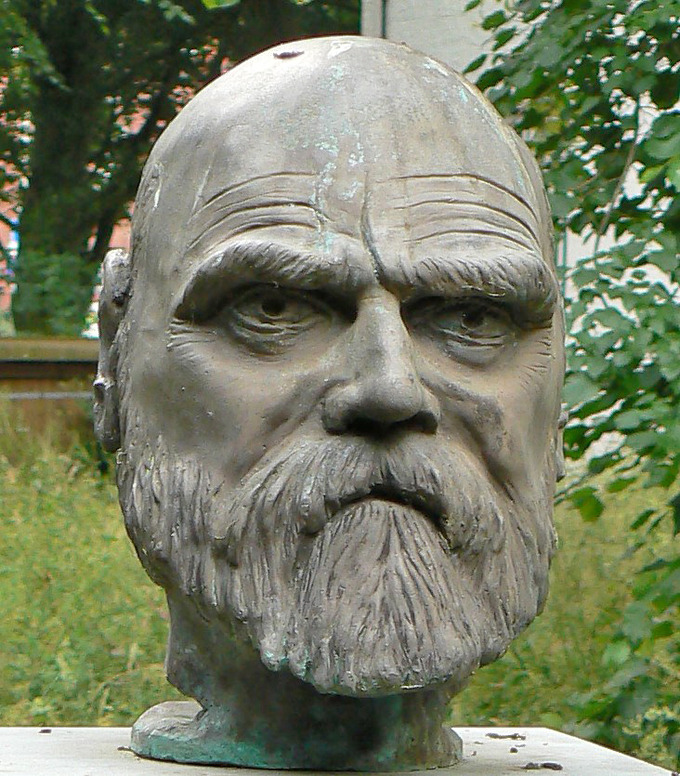

Durkheim’s Mechanical and Organic Solidarity

Key Points

Key Terms

Mechanical and Organic Solidarity

Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

Key Points

Key Terms

Gemeinschaft

Gesellschaft

Lenski’s Sociological Evolution Approach

Key Points

Key Terms

Technological Progress

Four Stages of Human Development

Population and Production

Contributors and Attributions

CC licensed content, Specific attribution