10.3: What Do I Speak About?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 106478

Learning Objectives

- Determine the general purpose of a speech.

- List strategies for narrowing a speech topic.

- Compose an audience-centered, specific purpose statement for a speech.

- Compose a thesis statement that summarizes the central idea of a speech.

- Compose a preview statement that highlights the main points of a speech.

General Purpose

The first step when developing a speech involves determining the general purpose of the speech. As mentioned earlier, there are only three general purposes: to inform, to persuade, and to inspire. Don’t forget the previous warning, if you’ve been told that you will be delivering an informative speech, you are automatically constrained from delivering a speech to persuade. In most public speaking classes, it will be easy to determine the general purpose of your speeches because generally, teachers will tell you the exact purpose for each speech in the class.

Choosing a Topic

Once you have determined (or been assigned) your general purpose, you can begin the process of choosing a topic. In this class, you may be given the option to choose any topic for your informative or persuasive speech, but in most academic, professional, and personal settings, there will be some parameters set that will help guide your topic selection. Speeches in future classes will likely be organized around the content being covered in the class. Speeches delivered at work will usually be directed toward a specific goal such as welcoming new employees, informing about changes in workplace policies, or presenting quarterly sales figures. We are also usually compelled to speak about specific things in our personal lives, like addressing a problem at our child’s school by speaking out at a school board meeting. In short, it’s not often that you’ll be starting from scratch when you begin to choose a topic.

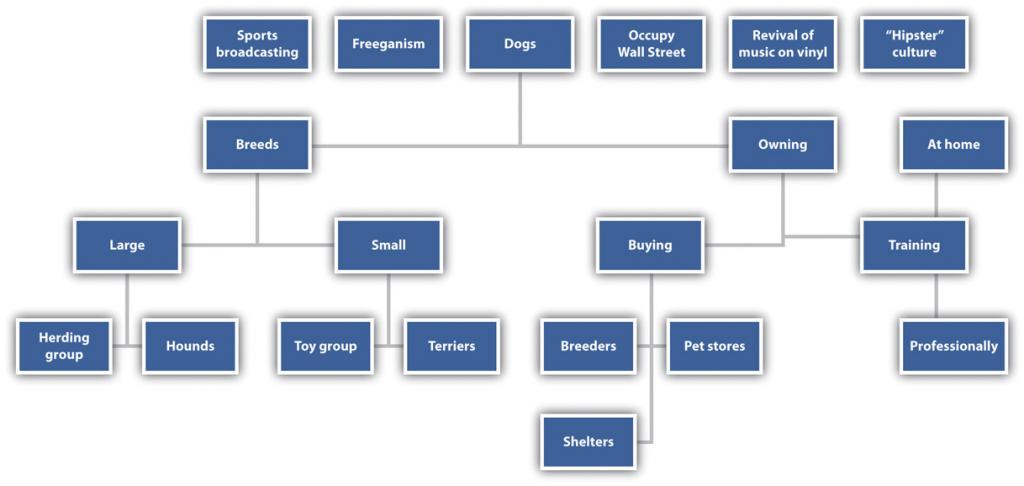

Whether you’ve received parameters that narrow your topic range or not, the first step in choosing a topic is brainstorming. Brainstorming involves generating many potential topic ideas in a fast-paced and non-judgmental manner. Brainstorming can take place multiple times as you narrow your topic. For example, you may begin by brainstorming a list of your personal interests that can then be narrowed down to a speech topic. It makes sense that you will enjoy speaking about something that you care about or find interesting. The research and writing will be more interesting, and the delivery will be easier since you won’t have to fake enthusiasm for your topic. Speaking about something you’re familiar with and interested in can also help you manage speaking anxiety. While it’s good to start with your personal interests, some speakers may get stuck here if they don’t feel like they can make their interests relevant to the audience. In that case, you can look around for ideas. If your topic is something that’s being discussed in newspapers, on television, in the lounge of your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s likely to be of interest and be relevant since it’s current. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows how brainstorming works in stages. A list of topics that interest the speaker is on the top row. The speaker can brainstorm subtopics for each idea to see which one may work the best. In this case, the speaker could decide to focus his or her informative speech on three common ways people come to own dogs: through breeders, pet stores, or shelters.

Overall you can follow these tips as you select and narrow your topic:

- Brainstorm topics that you are familiar with, interest you, and/or are currently topics of discussion.

- Choose a topic appropriate for the assignment/occasion.

- Choose a topic that you can make relevant to your audience.

- Choose a topic that you have the resources to research (access to information, people to interview, etc.).

Formulating a Specific Purpose Statement

Once you have brainstormed, narrowed, and chosen your topic, you can begin to draft your specific purpose statement. Your specific purpose is a one-sentence statement that includes the objective you want to accomplish in your speech. You do not speak aloud your specific purpose during your speech; you use it to guide your researching, organizing, and writing. A good specific purpose statement is audience-centered, agrees with the general purpose, addresses one main idea, and is realistic. This formula will help you in putting together your specific purpose statement:

Specific Communication Word (inform, explain, demonstrate, describe, define, persuade, convince, prove, argue)

Target Audience (my classmates, the members of the Social Work Club, my coworkers)

The Content (how to bake brownies, that Macs are better than PCs)

Each of these parts of the specific purpose is important. The first two parts make sure you are clear on your purpose and know specifically who will be hearing your message. However, we will focus on the last part here. The content part of the specific purpose statement must first be singular and focused, and the content must match the purpose. The word “and” really should not appear in the specific purpose statement since that would make it seem that you have two purposes and two topics. Obviously, the specific purpose statement’s content must be very narrowly defined and, well, specific. One mistake beginning speakers often make is to try to “cover” too much material. They tend to speak about the whole alphabet, A-Z on a subject, instead of just “T” or “L.” This comes from an emphasis on the topic more than the purpose, and from not keeping audience and context in mind. In other words, go deep (specific), not broad. Examples in this chapter will show what that means.

Second, the content must match the focus of the purpose word. A common error is to match an informative purpose with a persuasive content clause or phrase. For example,

To explain to my classmates why term life insurance is a better option than whole life insurance policies.

To inform my classmates about how the recent Supreme Court decision on police procedures during arrests is unconstitutional.

Sometimes it takes an unbiased second party to see where your content and purpose may not match.

Third, the specific purpose statement should be relevant to the audience. How do the purpose and its topic touch upon their lives, wallets, relationships, careers, etc.? It is also a good idea to keep in mind what you want the audience to walk away with or what you want them to know, to be able to do, to think, to act upon, or to respond to your topic—your outcome or result.

For example, “to explain to my classmates the history of NASA” would be far too much material and the audience may be unsure of its relevance. A more specific one such as “to inform my classmates about the decline of the Shuttle program” would be more manageable and closer to their experience. It would also reference two well-known historical tragedies involving the Shuttle program, the Challenger Disaster in 1986 and the Columbia Explosion in 2003. Here are several examples of specific purpose statements. Notice how they meet the standards of being singular, focused, relevant, and consistent.

To inform my classmates of the origin of the hospice movement.

To describe to my coworkers the steps to apply for retirement.

To define for a group of new graduate students the term “academic freedom.”

To explain to the Lions Club members the problems faced by veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

To persuade the members of the Greek society to take the spring break trip to Daytona Beach.

To motivate my classmates to engage in the College’s study abroad program.

To convince my classroom audience that they need at least seven hours of sleep per night to do well in their studies.

Now that you understand the basic form and function of a specific purpose statement, let’s look at how the same topic for a different audience will create a somewhat different specific purpose statement. Public speaking is not a “one-size-fits-all” proposition. Let’s take the subject of participating in the study abroad program. How would you change your approach if you were addressing first-semester freshmen instead of first-semester juniors? Or if you were speaking to high school students in one of the college’s feeder high schools? Or if you were asked to share your experiences with a local civic group that gave you a partial scholarship to participate in the program? You would have slightly different specific purpose statements although your experience and basic information are all the same.

For another example, let’s say that one of your family members has benefitted from being in the Special Olympics and you have volunteered two years at the local event. You could give a tribute (commemorative speech) about the work of Special Olympics (with the purpose to inspire), an informative speech on the scope or history of the Special Olympics, or a persuasive speech on why audience members should volunteer at next year’s event. “Special Olympics” is a keyword for every specific purpose, but the statements would otherwise be different.

Despite all the information given about specific purpose statements so far, the next thing you read will seem strange: Never start your speech by saying your specific purpose to the audience. In a sense, it is just for you and the instructor. For you, it’s like a note you might tack on the mirror or refrigerator to keep you on track. For the instructor, it’s a way for him or her to know you are accomplishing both the assignment and what you set out to do. Avoid the temptation to default to saying it at the beginning of your speech. It will seem awkward and repetitive.

Formulating a Central Idea Statement

While you will not actually say your specific purpose statement during your speech, you will need to clearly state what your focus and main points are going to be (preferably at the end of the introductory section of your speech). The statement that contains or summarizes a speech’s main points is commonly known as the central idea statement (or just the central idea).

Now, at this point, we need to make a point about terminology. Your instructor may call the central idea statement “the thesis” or “the thesis statement.” Your English composition instructor probably uses that term in your essay writing. Another instructor may call it the “main idea statement.” All of these are basically synonymous and you should not let the terms confuse you, but you should use the term your instructor uses.

That said, is the central idea statement the very same thing as the thesis sentence in an essay? Yes, in that both are letting the audience know without a doubt your topic, purpose, direction, angle, and/or point of view. No, in that the rules for writing a “thesis” or central idea statement in a speech are not as strict as in an essay. For example, it is acceptable in a speech to announce the topic and purpose, although it is usually not the most artful or effective way to do it. You may say,

“In this speech, I will try to motivate you to join me next month as a volunteer at the regional Special Olympics.”

That would be followed by a preview statement of what the speaker’s arguments or reasons for participating will be, such as,

“You will see that it will benefit the community, the participants, and you individually.”

However, another approach is to “capsulize” the purpose, topic, approach, and preview in one succinct statement.

“Your involvement as a volunteer in next month’s regional Special Olympics will be a rewarding experience that will benefit the community, the participants, and you personally.”

This last version is really the better approach and most likely the one your instructor will prefer.

So, you don’t want to just repeat your specific purpose in the central idea statement, but you do want to provide complete information. Also, unlike the formal thesis of your English essays, the central idea statement in a speech can and should use personal language (I, me, we, us, you, your, etc.) and should attempt to be attention-getting and audience-focused. And importantly, just like a formal thesis sentence, it must be a complete, grammatical sentence.

The point of your central idea statement in terms of your audience is to reveal and clarify the ideas or assertions you will be addressing in your speech, more commonly known as your main points, to fulfill your specific purpose. However, as you are processing your ideas and approach, you may still be working on them. Sometimes those main points will not be clear to you immediately. As much as we would like these writing processes to be straightforward, sometimes we find that we have to revise our original approach. This is why preparing a speech the night before you are giving it is a really, really bad idea. You need lots of time for the preparation and then the practice.

Sometimes you will hear the writing process referred to as “iterative.” This word means, among other things, that a speech or document is not always written in the same order as the audience finally experiences it. You may have noticed that we have not said anything about the introduction of your speech yet. Even though that is the first thing the audience hears, it may be one of the last parts you actually compose. It is best to consider your speech flexible as you work on it and to be willing to edit and revise. If your instructor asks you to turn the outline in before the speech, you should be clear on how much you can revise after that. Otherwise, it helps to know that you can keep editing your speech until you deliver it, especially while you practice.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): "Audience listens at Startup School" by Robert Scoble is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Here are some examples of pairs of specific purpose statements and central idea statements.

Specific Purpose: To explain to my classmates the effects of losing a pet on the elderly.

Central Idea: When elderly persons lose their animal companions, they can experience serious psychological, emotional, and physical effects.

Specific Purpose: To demonstrate to my audience the correct method for cleaning a computer keyboard.

Central Idea: Your computer keyboard needs regular cleaning to function well, and you can achieve that in four easy steps.

Specific Purpose: To persuade my political science class that labor unions are no longer a vital political force in the U.S.

Central Idea: Although for decades in the twentieth century labor unions influenced local and national elections, in this speech I will point to how their influence has declined in the last thirty years.

Specific Purpose: To motivate my audience to oppose the policy of drug testing welfare recipients.

Central Idea: Many voices are calling for welfare recipients to go through mandatory, regular drug testing, but this policy is unjust, impractical, and costly, and fair-minded Americans should actively oppose it.

Specific Purpose: To explain to my fellow civic club members why I admire Representative John Lewis.

Central Idea: John Lewis has my admiration for his sacrifices during the Civil Rights movement and his service to Georgia as a leader and U.S. Representative.

Specific Purpose: To describe how makeup is done for the TV show The Walking Dead.

Central Idea: The wildly popular zombie show The Walking Dead achieves incredibly scary and believable makeup effects, and in the next few min

Notice that in all of the above examples that neither the specific purpose nor the central idea ever exceeds one sentence. You may divide your central idea and the preview of the main points into two sentences or three sentences, depending on what your instructor directs. If your central idea consists of more than three sentences, then you probably are including too much information and taking up the time that is needed for the body of the speech. Additionally, you will have a speech trying to do too much and that goes overtime.

Problems to Avoid with Specific Purpose and Central Idea Statements

- The first problem many students have in writing their specific purpose statement has already been mentioned: specific purpose statements sometimes try to cover far too much and are too broad. For example:

To explain to my classmates the history of ballet.

Aside from the fact that this subject may be difficult for everyone in your audience to relate to, it is enough for a three-hour lecture, maybe even a whole course. You will probably find that your first attempt at a specific purpose statement will need refining. These examples are much more specific and much more manageable given the limited amount of time you will have.

To explain to my classmates how ballet came to be performed and studied in the U.S.

To explain to my classmates the difference between Russian and French ballet.

To explain to my classmates how ballet originated as an art form in the Renaissance.

To explain to my classmates the origin of the ballet dancers’ clothing.

- The second problem with specific purpose statements is the opposite of being too broad, in that some specific purposes statements are so focused that they might only be appropriate for people who are already extremely interested in the topic or experts in a field:

To inform my classmates of the life cycle of a new species of lima bean (botanists, agriculturalists).

To inform my classmates about the Yellow 5 ingredient in Mountain Dew (chemists, nutritionists).

To persuade my classmates that JIF Peanut Butter is better than Peter Pan. (organizational chefs in large institutions)

- The third problem happens when the “communication verb” in the specific purpose does not match the content; for example, persuasive content is paired with “to inform” or “to explain.” If you resort to the word “why” in the thesis, it is probably persuasive.

To inform my audience why capital punishment is unconstitutional. (This cannot be informative since it is taking a side)

To persuade my audience about the three types of individual retirement accounts. (This is not persuading the audience of anything, just informing)

To inform my classmates that Universal Studios is a better theme park than Six Flags over Georgia. (This is clearly an opinion, hence persuasive)

- The fourth problem exists when the content part of the specific purpose statement has two parts and thus uses “and.” A good speech follows the KISS rule—Keep It Simple, Speaker. One specific purpose is enough. These examples cover two different topics.

To explain to my audience how to swing a golf club and choose the best golf shoes.

To persuade my classmates to be involved in the Special Olympics and vote to fund better classes for the intellectually disabled.

To fix this problem, you will need to select one of the topics in these examples and speak on just that:

To explain to my audience how to swing a golf club.

OR

To explain to my audience how to choose the best golf shoes.

Of course, the value of this topic depends on your audience’s interest in golf and your own experience as a golfer.

- The fifth problem with both specific purpose and central idea statements is related to formatting. Some general guidelines need to be followed in terms of how you write out these elements of your speech:

- Do not write either statement as a question.

- Always use complete sentences for central idea statements and infinitive phrases (that is, “to …..”) for the specific purpose statement.

- Only use concrete language (“I admire Beyoncé for being a talented performer and businesswoman”), and avoid subjective or slang terms (“My speech is about why I think Beyoncé is the bomb”) or jargon and acronyms (“PLA is better than CBE for adult learners.”)

- Finally, the sixth problem occurs when the speech just gets off track of the specific purpose statement, in that it starts well but veers in another direction. This problem relates to the challenge of developing coherent main points, what might be called “the Roman numeral points” of the speech. The specific purpose usually determines the main points and the relevant structure. For example, if the specific purpose is:

To inform my classmates of the five stages of grief as described by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross.

There is no place in this speech for a biography of Dr. Kubler-Ross, arguments against this model of grief, therapies for those undergoing grief, or steps for the audience to take to get counseling. All of those are different specific purposes. The main points would have to be the five stages, in order, as Dr. Kubler-Ross defined them.

There are also problems to avoid in writing the central idea statement. As mentioned above, remember that:

- The specific purpose and central idea statements are not the same things, although they are related.

- The central idea statement should be clear and not complicated or wordy; it should “stand out” to the audience. As you practice delivery, you should emphasize it with your voice.

- The central idea statement should not be the first thing you say but should follow the steps of a good introduction.

Conclusion

One last word. You should be aware that all aspects of your speech are constantly going to change as you move toward actually giving your speech. The exact wording of your central idea may change and you can experiment with different versions for effectiveness. However, your specific purpose statement should not change unless there is a really good reason, and in some cases, your instructor will either discourage that, forbid it, or expect to be notified. There are many aspects to consider in the seemingly simple task of writing a specific purpose statement and its companion, the central idea statement. Writing good ones at the beginning will save you some trouble later in the speech preparation process.

Exercises

- Pay attention to the news (in the paper, on the Internet, television, or radio). Identify two informative and two persuasive speech topics that are based in current events.

- What if your informative speech has the specific purpose statement: To explain the biological and lifestyle cause of Type II diabetes. The assignment is a seven-minute speech, and when you practice it the first time, it is thirteen minutes long. Should you adjust the specific purpose statement? How?

References

Career Cruising, “Marketing Specialist,” Career Cruising: Explore Careers, accessed January 24, 2012, http://www.careercruising.com.

Greenwell, D., “You Might Not ‘Like’ Facebook So Much after Reading This…” The Times (London), sec. T2, January 13, 2012, 4–5.

Siegel, D. L., Timothy J. Coffey, and Gregory Livingston, The Great Tween Buying Machine (Chicago, IL: Dearborn Trade, 2004).

Solomon, M. R., Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2006), 10–11.