11.2: What Supporting Materials do I Need?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 107508

Learning Objectives

- Understand the use of supporting materials.

- Identify various types of supporting materials.

As you are researching for your speeches, we discussed that it is not a totally linear process. It would be nice if the process was like following a recipe, but it loops back and forth as you move toward crafting something that will effectively present your ideas and research. Even as you practice, you will make small changes to your basic outline, since the way something looks on paper and the way it sounds are sometimes different. For example, long sentences may look intelligent on paper, but they are hard to say in one breath and hard for the audience to understand. You will also find it necessary to use more repetition or restatement in oral delivery.

This section is about what you are searching for in your research, supporting materials. We will discuss: what they are, what they do, and how to use them effectively. Hopefully, you have already been thinking about how to support your ideas when you were finding a topic and crafting a central idea. Supporting material also relates directly to the previously mentioned presentation aids. Whereas presentation aids are visual or auditory supporting materials, this chapter will deal with verbal supporting materials.

Using your supporting materials effectively is essential because, as an audience, we crave detail and specifics. Let’s say you are discussing going out to eat with a group of friends. You suggest a certain restaurant and your friends make a comment about the restaurant that you have not heard or don’t accept at face value, so you ask in some way for an explanation, clarification, or proof. If they say, “Their servers are really rude,” you might ask, “What did they do?” If they say, “Their food is delicious,” you might ask, "What dish is good?" Likewise, if they say, “The place is nasty,” you will want to know what their health rating is or why your friends made this statement. We want to know specifics and are not satisfied with vagueness. Thinking about who your audience is and what they know and would like to know will help you tailor your information. Also try to incorporate proxemic information, meaning information that is geographically relevant to your audience. For example, if delivering a speech about prison reform to an audience made up of Californians, citing statistics from North Carolina prisons would not be as proxemic as citing information from California prisons. The closer you can get the information to the audience, the better.

Supporting material can be thought of as the specifics that make your ideas, arguments, assertions, points, or concepts real and concrete. Sometimes supporting materials are referred to as the “meat” on the bones of the outline, but we also like to think of them as pegs you create in the audience’s mind to hang the ideas on. Another even more useful idea is to think of them as pillars or supports for a bridge (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Without these supports, the bridge would just be a piece of concrete that would not hold up once cars start to cross it. Similarly, the points and arguments you are making in your speech may not hold up without the material to “support” what you are saying.

Of course, all supporting materials are not considered equal. Some are better at some functions or for some speeches than others. In general, there are two basic ways to think about the role of supporting materials. Either they:

- clarify, explain, or provide specifics (and therefore understanding) for the audience, or

- prove and back up arguments and therefore persuade the audience.

Of course, some can do both.

You might ask, how much supporting material is enough? The time you are allowed or required to speak will largely determine that. As we will discuss in your "Outlining" chapter, the supporting materials are found in the subpoints of your outline (A, B, etc.) and sub-subpoints (1, 2, etc.) You can see clearly on the outline how many you have and can omit one if time constraints demand that. However, in our experience as public speaking instructors, we find that students often struggle with having enough supporting materials. We often comment on a student’s speech that we wanted the student to answer more of the “what, where, who, how, why, when,” questions and add more description, proof, or evidence because their ideas were vague.

Students often struggle with the difference between the “main idea” and “supporting ideas.” For example, in this list, you will quickly recognize a commonality.

- Chocolate

- Vanilla

- Strawberry

- Butter Pecan

Of course, they are popular flavors of ice cream. The main idea is “Popular Flavors of Ice Cream” and the individual flavors are supporting materials to clarify the main idea; they “hold” it up for understanding and clarification. If the list were:

- Rocky Road

- Honey Jalapeno Pickle

- Banana Split

- Chocolate

- Wildberry Lavender

You would recognize two or three as ice cream flavors (not as popular) but #2 and #5 do not seem to fit the list (Covington, 2013). But you still recognize them as types of something and infer from the list that they have to do with ice cream flavors. “Ice cream flavors” is the general subject and the flavors are the particulars.

Those examples were easy. Let’s look at this one. One of the words in this list is the general, and the rest are the particulars.

- Love

- Emotion

- Sadness

- Disgust

- Tolerance

Emotion is a general category, and the list here shows specific emotions. Here is another:

- Spaying helps prevent uterine infections and breast cancer.

- Pets who live in states with high rates of spaying/neutering live longer.

- Your pet’s health is positively affected by being spayed or neutered.

- Spaying lessens the increased urge to roam.

- Male pets who are neutered eliminate their chances of getting testicular and prostate cancer.

Which one is the main point (the general idea), and which are the supporting points that include evidence to prove the main point? You should see that the third bullet point (“Your pet’s health is positively affected . . .”) would be a main point or argument in a persuasive speech on spaying or neutering your pet. The basic outline for the speech might look something like this:

- Spaying or neutering your pet is good for public health.

- Spaying or neutering your pet is good for your pet’s health.

- Spaying or neutering your pet is good for your family’s life and budget.

Of course, each of the four supporting points in this example (“helps uterine cancer in female pets, “etc.) cannot just be made up. The speaker would need to refer to or cite reliable statistics or testimony from veterinarians, researchers, public health organizations, and humane societies. For that reason, here is the more specific support, which you would use in a speech to be ethical and credible. Notice that the subpoints and sub-subpoints in this example use statistics and specific details to support the claims being made and provides sources.

2. Spaying or neutering your pet is good for your pet’s health.

A. Spaying helps prevent uterine infections and breast cancer, which is fatal in about 50 percent of dogs and 90 percent of cats, as found in the online article “Top Ten Reasons to Spay or Neuter Your Pet,” written in 2015 and posted on the website for the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

B. The article also states that pets who live in the states with the highest rates of spaying/neutering also live the longest.

- According to Natalie DiBlasio, writing for USA Today on May 7 of 2013, in Mississippi, the lowest-ranking state for pet longevity, 44% of the dogs are not neutered or spayed.

- She goes on to say that other issues affecting pet longevity have to do with climate, heartworm, and the income of owners.

C. The Human Society of America’s website features the August 2014 article, “Why You Should Spay/Neuter Your Pet,” which states that spaying lessens their urge to roam, exposure to fights with other animals, getting struck by cars, and other mishaps.

D. Also according to the same article, male pets who are neutered eliminate their chances of getting testicular and prostate cancer.

With all the sources available to you through reliable Internet and published sources, finding information is not difficult. Recognizing supporting information from the general idea you are trying to support or prove is more difficult, as is providing an adequate citation.

Along with clarifying and proving, supporting materials, especially narrative ones, also make your speech much more interesting and attention-getting. Ultimately, you will be perceived as a more credible speaker if you provide clarifying, probative (proof-giving and logical), and interesting supporting materials.

Types of Supporting Materials

Essentially, there are seven types of supporting materials: examples, narratives, definitions, descriptions, historical and scientific facts, statistics, and testimony. Each provides a different type of support, and you will want to choose the supporting materials that best help you make the point you want to get across to your audience.

Examples

This type of supporting material is the first and easiest to use but also easy to forget. Examples are almost always short, but concrete specific instances to illuminate a concept. They are designed to give audiences a reference point. If you were describing a type of architecture, you would obviously show visual aids of it and give verbal descriptions of it, but you could say, “You pass an example of this type of architecture every time you go downtown—City Hall.” An example is a cited case that is representative of a larger whole. Examples are especially beneficial when presenting information that an audience may not be familiar with. An example must be quickly understandable, something the audience can pull out of their memory or experience quickly.

You may pull examples directly from your research materials, making sure to cite the source. The following is an example used in a speech about the negative effects of standardized testing: “Standardized testing makes many students anxious, and even ill. On March 14, 2002, the Sacramento Bee reported that some standardized tests now come with instructions indicating what teachers should do with a test booklet if a student throws up on it.”

You may also cite examples from your personal experience, if appropriate: “I remember being sick to my stomach while waiting for my SAT to begin.”

You may also use hypothetical examples, which can be useful when you need to provide an example that is extraordinary or goes beyond most people’s direct experience. Capitalize on this opportunity by incorporating vivid descriptions into the example that appeal to the audience’s senses. Always make sure to indicate when you are using a hypothetical example, as it would be unethical to present an example as real when it is not. Including the word "imagine" or something similar in the first sentence of the example can easily do this.

Whether real or hypothetical, examples used as supporting material can be brief or extended. Brief examples are usually one or two sentences, as you can see in the following hypothetical example:

“Imagine that your child, little sister, or nephew has earned good grades for the past few years of elementary school, loves art class, and also plays on the soccer team. You hear the unmistakable sounds of crying when he or she comes home from school and you find out that art and soccer have been eliminated because students did not meet the federal guidelines for performance on standardized tests.”

Brief examples are useful when the audience is already familiar with a concept or during a review. Extended examples, sometimes called illustrations, are several sentences long and can be effective in introductions or conclusions to get the audience’s attention or leave a lasting impression. It is important to think about relevance and time limits when considering using an extended illustration. Since most speeches are given within time constraints, you want to make sure the extended illustration is relevant to your speech purpose and thesis and that it doesn’t take up a disproportionate amount of the speech. If a brief example or series of brief examples would convey the same content and create the same tone as the extended example, then, obviously, go with brevity.

The key to effectively using examples in your speeches is this: what is an example to you may not be an example to your audience if they have a different experience. Experienced speakers cannot use the same examples or pop culture references they used in class twenty years earlier. Television shows from twenty years ago are pretty meaningless to audiences today. Time and age are not the only reasons an example may not work with the audience. If you are a huge soccer fan speaking to a group who barely knows soccer, using a well-known soccer player as an example of perseverance or overcoming discrimination in the sports world may not communicate. It may only leave the audience members scratching their heads.

Additionally, one good, appropriate example is worth several less apt ones. Keep in mind that in the distinction between supporting materials that prove, those that clarify, and those that do both, examples are used to clarify.

Narratives

Narratives are stories or anecdotes that are useful in speeches to interest the audience and clarify, dramatize, and emphasize ideas. They have, if done well, strong emotional power. They can be used in the introduction, the body, and the conclusion of the speech. They can be short, as anecdotes usually are. Think of the stories you often see in Readers’ Digest, human interest stories on the local news, or what you might post on Facebook about a bad experience you had at the DMV. They could be longer, although they should not take up large portions of the speech.

Narratives can be personal, literary, historical, or hypothetical.

Personal narratives can be helpful in situations where you desire to:

- Relate to the audience on a human level, especially if they may see you as competent but not really similar or connected to them.

- Build your credibility by mentioning your experience with a topic.

Of course, personal narratives must be true. They must also not portray you as more competent, experienced, brave, intelligent, etc., than you are; in other words, along with being truthful in using personal narratives, you should be reasonably humble.

An example of a literary narrative might be one of Aesop’s fables, a short story by O’Henry, or an appropriate tale from another culture. Keep in mind that because of their power, stories tend to be remembered more than other parts of the speech. Do you want the story to overshadow your content? Scenes from films would be another example of a literary narrative, but as with examples, you must consider the audience’s frame of reference and if they will have seen the film.

Historical narratives (sometimes called documented narratives) have power because they can also prove an idea as well as clarify one. In using these, you should treat them as fact and therefore give a citation as to where you found the historical narrative. By “historical” we do not mean the story refers to something that happened many years ago, only that it has happened in the past and there were witnesses to validate the happening.

If you were trying to argue for the end to the death penalty because it leads to unjust executions, one good example of a person who was executed and then found innocent afterward would be both emotional and probative. Here, be careful of using theatrical movies as your source of historical narrative. Hollywood likes to change history to make the story they want. For example, many people think Braveheart is historically accurate, but it is off on many key points—even the kilts, which were not worn by the Scots until the 1600s.

Hypothetical narratives are ones that could happen but have not yet. To be effective, they should be based on reality. Here are two examples:

Picture this incident: You are standing in line at the grocery checkout, reading the headlines on the Star and National Enquirer for a laugh, checking your phone. Then, the middle-aged man in front of you grabs his shoulder and falls to the ground, unconscious. What would you do in a situation like this? While it has probably never happened to you, people have medical emergencies in public many times a day. Would you know how to respond?

Imagine yourself in this situation. It is 3:00 in the morning. You are awakened from a pretty good sleep by a dog barking loudly in the neighborhood. You get up and see green lights coming into your house from the backyard. You go in the direction of the lights and unlock your back door and there, right beside your deck, is an alien spaceship. The door opens and visitors from another planet come out and invite you in, and for the next hour, you tour their ship. You can somehow understand them because their communication abilities are far advanced from ours. Now, back to reality. If you were in a foreign country, you would not be able to understand a foreign language unless you had studied it. That is why you should learn a foreign language in college.

Obviously, the second is so “off-the-wall” that the audience would be wondering about the connection, although it definitely does attract attention. If using a hypothetical narrative, be sure that it is clear that the narrative is hypothetical, not factual. Because of their attention-getting nature, hypothetical narratives are often used in introductions.

Definitions

When we use the term “definition” here as supporting material, we are not talking about something you can easily find from the dictionary or from the first thing that comes up on Google, such as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

First, using a dictionary definition does not really show your audience that you have researched a topic (anyone can look up a definition in a few seconds). Secondly, does the audience need a definition of a word like “love,” “bravery,” or “commitment?” They may consider it insulting for you to provide them the definition of those words.

To define means to set limits on something; defining a word is setting limits on what it means, how the audience should think about the word, and/or how you will use it. You only need to define words that would be unfamiliar to the audience or words that you want to use in a specialized way.

You need to anticipate audience confusion and define legal, medical, military, technical, or other forms of "jargon" or "slang." Some of these words may be in foreign languages, such as Latin (habeas corpus, quid pro quo). Some of them may be acronyms; CBE is a term being used currently in higher education that means “Competency-Based Education.” That is part of a definition, but not a full one—what is "competency-based education?" To answer that question, you should do your best to find an officially accepted definition and cite it.

You may want to use a stipulated definition early in your speech. In this case, you clearly tell the audience how you are going to use a word or phrase in your speech.“When I use the phrase 'liberal democracy' in this speech, I am using it in the historical sense of a constitution, representative government, and elected officials, not in the sense of any particular issues that are being debated today between progressives and conservatives.”

This is a helpful technique and makes sure your audience understands you, but you would only want to do this for terms that have confusing or controversial meanings for some. Keep in mind that repeating a definition verbatim from a dictionary often leads to fluency hiccups, because definitions are not written to be read aloud. It’s a good idea to put the definition into your own words (still remembering to cite the original source) to make it easier for you to deliver.

Classification and Differentiation

This is a fancy way of saying “X is a type of Y, but it is different from the other Ys in that . . .” “A bicycle is a type of vehicle that has two wheels, handlebars instead of a steering wheel, and is powered by the feet of the driver.” Obviously, you know what a bicycle is and it does not need defining, so here are some better examples:

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) is a (type of) surgical procedure that (how is it different) involves the placement of an adjustable silicone belt around the upper portion of the stomach using a laparoscope. The band can be tightened by adding saline to fill the band like blowing air into a doughnut-shaped balloon. The band is connected to a port that is placed under the skin of the abdomen. This port is used to introduce or remove saline into the band.

Gestational diabetes is a (type of) diabetic condition (how is it different) that appears during pregnancy and usually goes away after the birth of the baby.

Social publishing platforms are a (type of) social medium where (how is it different) long and short-form written content can be shared with other users.

Operational Definitions

Operational definitions give examples of an action or idea to define it. If we were to define “quid pro quo sexual harassment” operationally, we might use a hypothetical narrative of a female employee who is pressured by her supervisor to date him and told she must go out with him socially to get a promotion. Operational definitions do not have to be this dramatic, but they do draw a picture and answer the question, “What does this look like in real life?” rather than using synonyms to define.

Definition by Contrast or Comparison

You can define a term or concept by comparison or telling what it is similar to or different from. This method requires the audience to have an understanding of whatever you are using as the point of contrast or comparison. When alcoholism or drug addiction is defined as a disease, that is a comparison. Although not caused by a virus or bacteria, addiction disorder has other qualities that are disease-like.

When you are defining, by contrast, you are pointing how a concept or term is distinct from another more familiar one. For example, “pop culture” is defined as different from “high culture” in that, traditionally, popular culture has been associated with people of lower socioeconomic status (i.e. less wealth or education). High culture, on the other hand, is associated with the “official” culture of the more highly educated within the upper classes. Here, the definition of popular culture is clarified by highlighting the differences between it and high culture.

A similar form of definition by contrast is defining by negation, which is stipulating what something is not. This famous quotation from Nelson Mandela is an example: “I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear.” Here, Mandela is helping us draw limits around a concept by saying what it is not.

Analogies involve a comparison of ideas, items, or circumstances. When you compare two things that actually exist, you are using a literal analogy—for example, “Germany and Sweden are both European countries that have had nationalized health care for decades.” Another type of literal comparison is a historical analogy. In Mary Fisher’s now famous 1992 speech to the Republican National Convention, she compared the silence of many US political leaders regarding the HIV/AIDS crisis to that of many European leaders in the years before the Holocaust.

A figurative analogy compares things that are not normally related, often relying on metaphor, simile, or other figurative language devices. In the following example, wind and revolution are compared: “Just as the wind brings changes in the weather, so does revolution bring change to countries.”

When you compare differences, you are highlighting contrast—for example, “Although the United States is often thought of as the most medically advanced country in the world, other Western countries with nationalized health care have lower infant mortality rates and higher life expectancies.” To use analogies effectively and ethically, you must choose ideas, items, or circumstances to compare that are similar enough to warrant the analogy. The more similar the two things you’re comparing, the stronger your support. If an entire speech on nationalized health care was based on comparing the United States and Sweden, then the analogy isn’t too strong, since Sweden has approximately the same population as the state of North Carolina. Using the analogy without noting this large difference would be misrepresenting your supporting material. You could disclose the discrepancy and use other forms of supporting evidence to show that despite the population difference the two countries are similar in other areas to strengthen your speech.

Descriptions

The key to description is to think in terms of the five senses: sight (visual; how does the thing look in terms of color, size, shape), hearing (auditory; volume, musical qualities), taste (gustatory; sweet, bitter, salty, sour, gritty, smooth, chewy), smell (olfactory; sweet, rancid, fragrant, aromatic, musky), and feel (tactile; rough, silky, nubby, scratchy). The words kinesthetic (movement of the body) and organic (feelings related to the inner workings of the body) can be added to those senses to describe an internal physical feeling, such as straining muscles or pain (kinesthetic) and nausea or the feelings of heightened emotions (organic).

Description as a method of support also depends on details or answering the five questions of what, where, how, who, when. To use description, you must dig deeper into your vocabulary and think concretely. This example shows that progression.

- Furniture

- A chair

- A lounge chair

- An Art Deco lounge chair

- An old green velvet upholstered wooden Art Deco lounge chair.

- An old green velvet upholstered wooden Art Deco lounge chair with several scratches on the legs.

As you add more description, two things happen. The “camera focus” becomes clearer, but you also add tone or attitude. A recliner is one thing, but who buys a lime green velvet recliner? And someone sat in it smoked and was sloppy about it. In this case, the last line is probably too much description unless you want to paint a picture of a careless person with an odd taste in furniture.

A description is useful as supporting material in terms of describing processes. Describing processes requires detail and not taking for granted what the audience already knows. Some instructors use the “peanut butter sandwich” example to make this point: How would you describe making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich to someone who had never seen a sandwich, peanut butter, or jelly? You would need to put yourself in their shoes to describe the process and not assume they know that the peanut butter and jelly go on the inside, facing surfaces of the bread and that two pieces of bread are involved.

Historic and Scientific Fact

This type of supporting material is useful for clarification but is especially useful for proving a point. President John Adams is quoted as saying, “Facts are stubborn things,” but that does not mean everyone accepts every fact as a fact, or that everyone is capable of distinguishing a fact from an opinion. A fact is defined by the Urban Dictionary as “The place most people in the world tend to think their opinions reside.” This is a humorous definition, but often true about how we approach facts. The meaning of “fact” is complicated by the context in which it is being used. The National Center for Science Education (2008) defines fact this way:

In science, an observation that has been repeatedly confirmed and for all practical purposes is accepted as ‘true.’ Truth in science, however, is never final and what is accepted as a fact today may be modified or even discarded tomorrow.

Another source explains fact this way:

[Fact is] a truth known by actual experience or observation. The hardness of iron, the number of ribs in a squirrel’s body, the existence of fossil trilobites, and the like are all facts. Is it a fact that electrons orbit around atomic nuclei? Is it a fact that Brutus stabbed Julius Caesar? Is it a fact that the sun will rise tomorrow? None of us has observed any of these things - the first is an inference from a variety of different observations, the second is reported by Plutarch and other historians who lived close enough in time and space to the event that we trust their report, and the third is an inductive inference after repeated observations. (“Scientific Thought: Facts, Hypotheses, Theories, and all that stuff”)

Without getting into a philosophical dissertation on the meaning of truth, for our purposes facts are pieces of information with established “backup.” You can cite who discovered the fact and how other authorities have supported it. Some facts are so common that most people don’t know where they started—who actually discovered that the water molecule is two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen (H2O)? But we could find out if we wanted to (it was, by the way, the 18th-century chemist Henry Cavendish). In using scientific and historical facts in your speech, do not take citations for granted. If it is a fact worth saying and a fact new to the audience, assume you should cite the source of the fact, getting as close to the original as possible.

Also, the difference between a historical narrative (mentioned above) and a historical fact has to do with length. A historical fact might just be a date, place, or action, such as “President Ronald Reagan was shot by John Hinckley on March 30, 1981, in front of Washington, D.C. Hilton Hotel.” A historical narrative would go into much more detail and add dramatic elements, such as this assassination attempt from the point of view of Secret Service agents.

Statistics

Statistics are misunderstood. First, the meaning of the term is misunderstood. Statistics are not just numbers or numerical facts. The essence of statistics is the collection, analysis, comparison, and interpretation of numerical data, understanding its comparison with other numerical data. For example, it is a numerical fact that the population of the U.S., according to the 2010 census, was 308,700,000. This is a 9.7% increase from the 2000 census; this comparison is a statistic. However, for the purpose of simplicity, we will deal with both numerical facts and real statistics in this section.

Statistics are very credible in our society, as evidenced by their frequent use by news agencies, government offices, politicians, and academics. As a speaker, you can capitalize on the power of statistics if you use them appropriately. Unfortunately, statistics are often misused by speakers who intentionally or unintentionally misconstrue the numbers to support their argument without examining the context from which the statistic emerged. All statistics are contextual, so plucking a number out of a news article or a research study and including it in your speech without taking the time to understand the statistic is unethical.

Although statistics are popular as supporting evidence, they can also be boring. There will inevitably be people in your audience who are not good at processing numbers. Even people who are good with numbers have difficulty processing through a series of statistics presented orally. Remember that we have to adapt our information to listeners who don’t have the luxury of pressing a pause or rewind button. For these reasons, it’s a good idea to avoid using too many statistics and to use startling examples when you do use them. Startling statistics should defy our expectations. When you give the audience a large number that they would expect to be smaller or vice versa, you will be more likely to engage them, as the following example shows: “Did you know that 1.3 billion people in the world do not have access to electricity? That’s about 20 percent of the world’s population according to a 2009 study on the International Energy Agency’s official website.”

You should also repeat key statistics at least once for emphasis. In the previous example, the first time we hear the statistic "1.3 billion," we don’t have any context for the number. Translating that number into a percentage in the next sentence repeats the key statistic, which the audience now has context for, and repackages the information into a percentage, which some people may better understand. You should also round long numbers up or down to make them easier to speak. Make sure that rounding the number doesn’t distort its significance. Rounding 1,298,791,943 to 1.3 billion, for example, makes the statistic more manageable and doesn’t alter the basic meaning. It is also beneficial to translate numbers into something more concrete for visual or experiential learners by saying, for example, “That’s equal to the population of four Unites States of America.” While it may seem easy to throw some numbers in your speech to add to your credibility, it takes more work to make them impactful, memorable, and effective.

Statistics are also misunderstood because the science of statistics is difficult. Even terms like mean, median, and mode often confuse people. Before you can use statistics in a speech, you should have a basic understanding of them.

Mean is the same as the mathematical average, something you learned to do early in math classes. Add up the figures and divide by the number of figures.

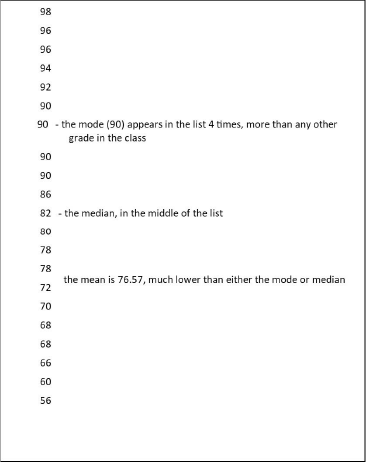

The median, however, is the middle number in a distribution. If all salaries of ballplayers in MLB were listed from highest to lowest, the one in the exact middle of the list would be the median. You can tell from this that it probably will not be the same as the average, and it rarely is; however, the terms “median” and “mean” are often interchanged carelessly. Mode is the name for the most frequently occurring number in the list. As an example, Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) is a list of grades from highest to lowest that students might make on a midterm in a class. The placement of mean, median, and mode are noted.

Percentages have to do with ratios. There are many other terms you would be introduced to in a statistics class, but the point remains: be careful of using a statistic that sounds impressive unless you know what it represents. There is an old saying about “figures don’t lie, but liars figure” and another, “There are liars, damn liars, and statisticians.” These sayings are exaggerations but they point out that we are inundated with statistical information and often do not know how to process it. Another thing to watch when using numerical facts is not to confuse your billions and your millions. There is a big difference. If you say that 43 billion people in the US are without adequate health care, you will probably confuse your audience, since the population of the planet is around 7 billion!

In using statistics, you are probably going to use them as proof more than an explanation. Statistics are considered a strong form of proof. Here are some guidelines for using them effectively in a presentation.

- Use statistics as support, not as the main point. The audience may cringe or tune you out for saying, “Now I’d like to give you some statistics about the problem of gangs in our part of the state.” That sounds as exciting as reading the telephone book! Use the statistics to support an argument. “Gang activity is increasing in our region. For example, it is increasing in the three major cities. Mainsville had 450 arrests for gang activity this year alone, up 20% from all of last year.” This example ties the numerical fact (450 arrests) and the statistical comparison (up 20%) to an argument. The goal is to weave or blend the statistics seamlessly into the speech, not have them stand alone as a section of the speech.

- Always provide the source of the statistic. In the previous example, it should read, “According to a report published on the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s website, Mainsville had 450 arrests . . .” There are a number of “urban myth” statistics floating around that probably have a basis in some research done at some point in time, but that research was outlived by the statistic. An audience would have reason to be skeptical if you cannot provide the name of the researcher or organization that backs up the statistics and numerical data. By the way, it is common for speakers and writers to say “According to research” or “According to studies.” This tag is essentially meaningless and actually a logical fallacy. Give a real source to support your argument.

- In regard to sources, depend on the reliable ones. Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), originally published in Wrench, Goding, Johnson, and Attias (2011), lists valid websites providing statistical information.

- Do not overuse statistics. While there is no hard and fast rule on how many to use, there are other good supporting materials and you would not want to depend on statistics alone. You want to choose the statistics and numerical data that will strengthen your argument the most and drive your point home. Statistics can have emotional power as well as probative value if used sparingly.

- Use graphs to display the most important statistics. If you are using presentation software such as PowerPoint, you can create your own basic pie, line, or bar graphs, or you can borrow one and put a correct citation on the slide. However, you do not need to make a graph for every single statistic.

- Explain your statistics as needed, but do not make your speech a statistics lesson. Explain the context of the statistics. If you say, “My blog has 500 subscribers” to a group of people who know little about blogs, that might sound impressive, but is it? You can also provide a story of an individual, and then tie the individual into the statistic. After telling a story of the daily struggles of a young mother with multiple sclerosis, you could follow up with “This is just one story in the 400,000 people who suffer from MS in the United States today, according to National MS Society.”

- If you do your own survey or research and use numerical data from it, explain your methodology. “In order to understand the attitudes of freshmen at our college about the subject of open-source textbooks, I polled 150 first-year students, only three of whom were close friends, asking them this question: ‘Do you agree that our college should encourage the faculty to use open-source textbooks?’ Seventy-five percent of them indicated that they agreed with the statement.”

- It goes without saying that you will use the statistic ethically, that there will be no distortion of what the statistic means. However, it is acceptable and a good idea to round up numerical data to avoid overwhelming the audience. Earlier we used the example of the U.S. census, stating the population in 2010 was 308.7 million. That is a rounded figure. The actual number was 308,745,538, but saying “almost 309 million” or “308.7 million” will serve your purposes and not be unethical.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Statistics-Oriented Website

| Website | Type of Information |

|---|---|

| http://www.bls.gov/bls/other.htm | Bureau of Labor Statistics provides links to a range of websites for labor issues related to a vast range of countries. |

| http://bjs.gov | Bureau of Justice Statistics provides information on crime statistics in the United States. |

| http://www.census.gov | US Census Bureau provides a wide range of information about people living in the United States. |

| https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ | National Center for Health Statistics is a program conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It provides information on a range of health issues in the United States. |

| http://www.stats.org | STATS is a nonprofit organization that helps people understand quantitative data. It also provides a range of data on its website. |

| http://ropercenter.cornell.edu/ | Roper Center for Public Opinion provides data related to a range of issues in the United States. |

| http://www.nielsen.com | Nielsen provides data on consumer use of various media forms. |

| http://www.gallup.com | Gallup provides public opinion data on a range of social and political issues in the United States and around the world. |

| http://www.adherents.com | Adherents provides both domestic and international data related to religious affiliation. |

| http://people-press.org | Pew Research Center provides public opinion data on a range of social and political issues in the United States and around the world. |

- Additionally, do not make statistics mean what they do not mean. Otherwise, you would be pushing the boundaries on ethics. In the example about your survey of students, if you were to say, “75% of college freshmen support . . . .” That is not what the research said. Seventy-five percent of the students you surveyed indicated agreement, but since your study did not meet scientific standards regarding the size of the sample and how you found the sample, you can only use the information in relation to students in your college, not the whole country. One of the authors had a statistics professor who often liked to say, “Numbers will tell you whatever you want if you torture them long enough,” meaning you can always twist or manipulate statistics to meet your goals if you want to.

- An effective technique with numerical data is to use physical comparisons. “The National Debt is 17 trillion dollars. What does that mean? It means that every American citizen owes $55,100.” “It means that if the money were stacked as hundred dollar bills, it would go to . . .” Or another example, “There are 29 million Americans with diabetes. That is 9.3%. In terms closer to home, of the 32 people in this classroom, 3 of us would have diabetes.” Of course, in this last example, the class may not be made up of those in risk groups for diabetes, so you would not want to say, “Three of us have diabetes.” It is only a comparison for the audience to grasp the significance of the topic.

- Finally, because statistics can be confusing, slow down when you say them, give more emphasis, gesture—small ways of helping the audience grasp them.

Testimony

Testimony is quoted information from people with direct knowledge about a subject or situation. Some quotations you just use because they are funny, compelling, or attention-getting. They work well as openings to introductions. Other types of testimony are more useful for proving your arguments. Testimony can also give an audience insight into the feelings or perceptions of others. We normally think in terms of the testimonies of people in courtrooms and other types of hearings. Lawyers know that juries want to hear testimony from experts, eyewitnesses, and friends and family. Speech audiences are similar.

When Toyota cars were malfunctioning and being recalled in 2010, mechanics and engineers were called to testify about the technical specifications of the car (expert testimony), and car drivers like the soccer mom who recounted the brakes on her Prius suddenly failing while she was driving her kids to practice were also called (peer testimony). When using testimony, make sure you indicate whether it is expert or peer by sharing with the audience the context of the quote. Share the credentials of experts (education background, job title, years of experience, etc.) to add to your credibility or give some personal context for the peer testimony (eyewitness, personal knowledge, etc.).

Testimony is the words of others. You might think of them as quoted material. Obviously, all quoted material or testimony is not the same. Some quotations you just use because they are funny, compelling, or attention-getting. They work well as openings to introductions. Other types of testimony are more useful for proving your arguments. Testimony can also give an audience insight into the feelings or perceptions of others. Testimony is basically divided into two categories: expert and peer.

Expert Testimony

Expert testimony is from people who are credentialed or recognized experts in a given subject. What is an expert? Here is a quotation of the humorous kind: An expert is “one who knows more and more about less and less” (Nicholas Butler). Actually, an expert for our purposes is someone with recognized credentials, knowledge, education, and/or experience in a subject. Experts spend time studying the facts and putting the facts together. They may not be scholars who publish original research but they have in-depth knowledge. They may have certain levels of education, or they have real-world experience in the topic.

For example, one of the authors is attending a quilt show this week to talk to experts in quilting. This expertise was gained through years of making, preserving, reading about, and showing quilts, even if they never took Quilting 101 in college. To quote an expert on expertise, “To be an expert, someone needs to have considerable knowledge on a topic or considerable skill in accomplishing something” (Weinstein, 1993). In using expert testimony, you should follow these guidelines:

- Use the expert’s testimony in his or her relevant field, not outside of it. A person may have a Nobel Prize in economics, but that does not make him or her an expert in biology.

- Provide at least some of the expert’s relevant credentials.

- Choose experts to quote whom your audience will respect and/or whose name or affiliations they will recognize as credible.

- Make it clear that you are quoting the expert testimony verbatim or paraphrasing it. If verbatim, say “Quote . . . end of quote” (not unquote—you cannot unquote someone).

- If you interviewed the expert yourself, make that clear in the speech also. “When I spoke with Dr. Mary Thompson, principal of Park Lake High School, on October 12, she informed me that . . .”

Expert testimony is one of your strongest supporting materials to prove your arguments, but in a sense, by clearly citing the source’s credentials, you are arguing that your source is truly an expert (if the audience is unfamiliar with him or her) in order to validate his or her information.

Peer Testimony

Peer testimony is often a recounting of a person’s experiences, which is more subjective. Any quotation from a friend, family member, or classmate about an incident or topic would be peer testimony. It is useful in helping the audience understand a topic from a personal point of view. For example, in the spring of 2011, a devastating tornado came through the town where one of the authors and many of their students live. One of those students gave a dramatic personal experience speech in class about surviving the tornado in a building that was destroyed and literally disappeared. They survived because she and her coworkers at their chain restaurant were able to get to safety in the freezer. While she may not have had an advanced degree in a field related to tornadoes or the destruction they can cause, this student certainly had a good deal of knowledge on the subject based on her experience of surviving a tornado. However, do not present any old testimony of a peer or friend as if it were expert or credentialed.

“Getting Competent”: Choosing the Right Supporting Material

As you sift through your research materials to find supporting material to incorporate into your speech, you will want to include a variety of information types. Choosing supporting material that is relevant to your audience will help make your speech more engaging. As was noted earlier, a speaker should consider the audience throughout the speech-making process. Imagine you were asked to deliver a speech about your college or university. To get some practice adapting supporting material to various audiences, provide an example of each type of supporting material that is tailored to the following specific audiences. Include an example, a narrative, a definition, a description, a historical or scientific fact, a statistic, and a testimony.

- Incoming first-year students

- Parents of incoming first-year students

- Alumni of the college or university

- Community members that live close to the school

Key Takeaways

- Supporting material can be thought of as the specifics that make your ideas, arguments, assertions, points, or concepts real and concrete.

- Speakers should include a variety of supporting material from their research sources in their speeches. These types of supporting material include examples, narratives, definitions, descriptions, historical and scientific facts, statistics, and testimony.

Exercises

- Getting integrated: Identify some ways that research skills are helpful in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic.

- Go to the library webpage for your school. What are some resources that will be helpful for your research? Identify at least two library databases and at least one reference librarian. If you need help with research, what resources are available?

- What are some websites that you think are credible for doing college-level research? Why? What are some websites that are not credible? Why?