Section 8.4: Social Institutions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 107080

- Erika Gutierrez, Janét Hund, Shaheen Johnson, Carlos Ramos, Lisette Rodriguez, & Joy Tsuhako

- Long Beach City College, Cerritos College, & Saddleback College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Education

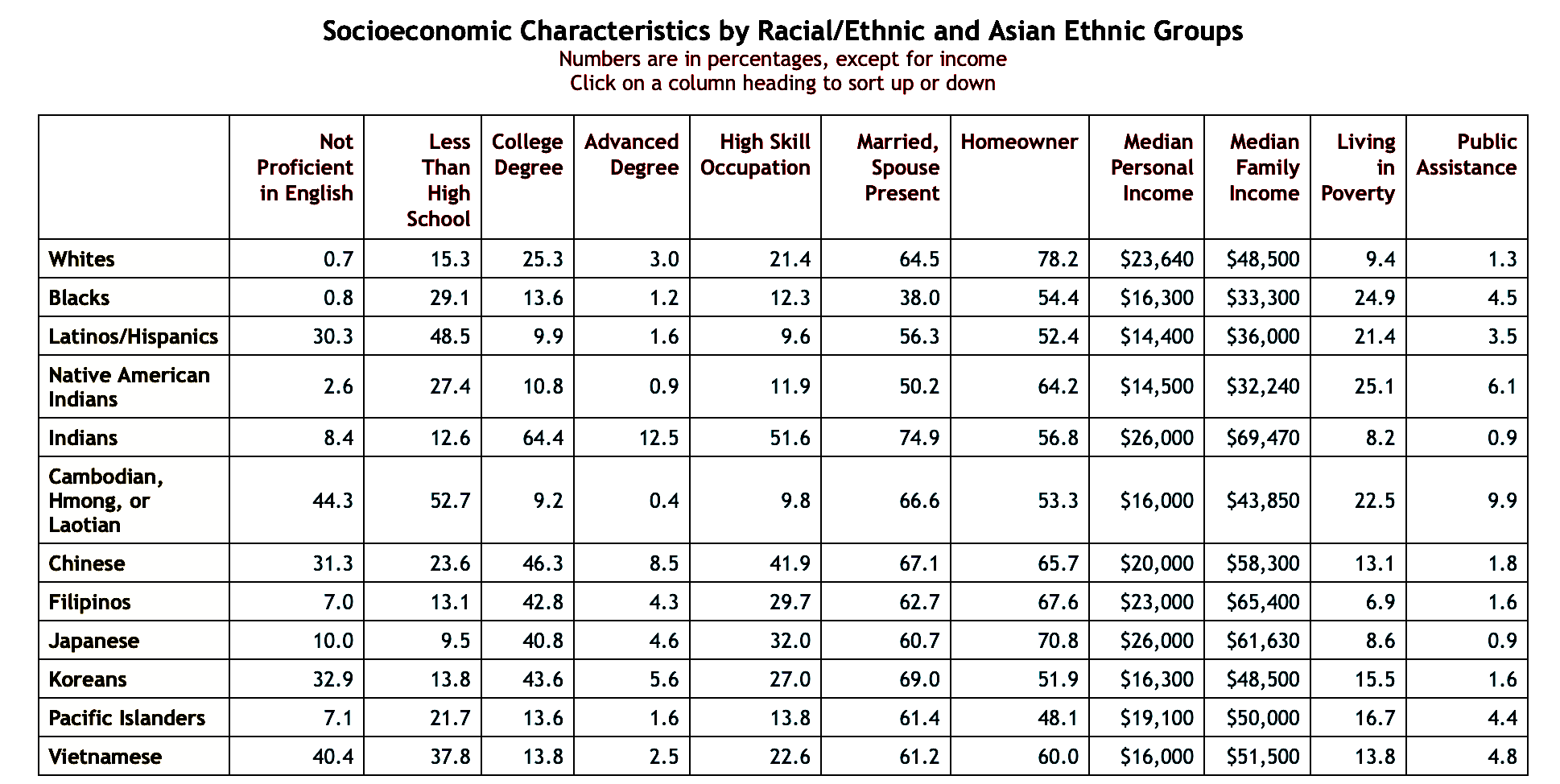

In a lot of ways, Asian Americans have done remarkably well in achieving "the American dream" of getting a good education, working at a good job, and earning a good living. So much so that the image many have of Asian Americans is that we are the "model minority" -- a bright, shining example of hard work and patience whose example other people of colors should follow (Wu, 2018). However, the practical reality is slightly more complicated than that. It is true that in many ways, Asian Americans have done very well socially and economically. The data in Table 9.4.1 was calculated using the 2000 Census Public Use Microdata Samples, then comparing the major racial/ethnic groups among different measures of what sociologists call "socioeconomic achievement."

These numbers tell you that among the five major racial/ethnic groups in the U.S., Asian Americans have the highest college degree attainment rate, rates of having an advanced degree (professional or Ph.D.), median family income, being in the labor force, rate of working in a "high skill" occupation (executive, professional, technical, or upper management), and median Socioeconomic Index (SEI) score that measures occupational prestige. Yes, in these categories, Asians even outperform whites. Asian Americans seem to have done so well that magazines such as Newsweek and respected television shows such as 60 Minutes proclaim us to be the "model minority."

Many people go even further and argue that since Asian Americans are doing so well, we no longer experience any discrimination and that Asian Americans no longer need public services such as bilingual education, government documents in multiple languages, and welfare. Further, using the first stereotype of Asian Americans, many just assume that all Asian Americans are successful and that none of us are struggling.

On the surface, it may sound rather benign and even flattering to be described in those terms. However, for every Chinese American or South Asian who has a college degree, the same number of Southeast Asians are still struggling to adapt to their lives in the U.S. For example, as shown in the tables in the Socioeconomic Statistics & Demographics article, Vietnamese Americans only have a college degree attainment rate of 20%, less than half the rate for other Asian American ethnic groups. The rates for Laotians, Cambodians, and Hmong are even lower at less than 10% (Ty, 2017).

The results show that as a whole Asian American families have higher median household incomes than white families. However, this is because in most cases, the typical Asian American family tends to have more members who are working than the typical white family. It's not unusual for an Asian American family to have four, five, or more members working. A more telling statistic is median personal income (also known as per capita income). The results above show that Asian Americans still trail whites on this very important measure.

Another telling statistic is how much more money a person earns with each additional year of schooling completed, or what sociologists call "returns on education." Using this measure, research consistently shows that for each additional year of education attained, whites earn another $522. In contrast, returns on each additional year of education for a Japanese American is only $438. For a Chinese American, it's $320. For Blacks, it's even worse at only $284. What this means is that basically, a typical Asian American has to get more years of education just to make the same amount of money that a typical white makes with less education.

Another point is that even despite the real successes we've achieved, Asian Americans are still significantly underrepresented in positions of political leadership at the local, regional, state, and federal levels (despite the successes of a few individuals such as Norman Mineta and Elaine Chao) -- just like Blacks, Latinos, and American Indians. In the corporate world, Asian Americans are underrepresented as CEOs, board members, and high-level supervisors -- just like Blacks, Latinos, and American Indians.

This is not to say that there aren't Asians Americans out there who are quite successful and have essentially achieved the American dream. The point is that just because many Asian Americans have "made it," it does not mean that all Asian Americans have made it. In many ways, Asian Americans are still the targets of much prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination. For instance, the persistent belief that "all Asians are smart" puts a tremendous amount of pressure on many Asian Americans. Many, particularly Southeast Asians, are not able to conform to this unrealistic expectation and in fact, have the highest high school dropout rates in the country (Chou, 2008).

The Economy

Self-Employment Then and Now

In the early era of Asian American history, the Gold Rush was one of the strongest pull factors that led many Chinese to come to the U.S. to find their fortune and return home rich and wealthy. In addition, many Chinese (and later other Asian groups as well) also came to Hawai'i as contract laborers to work in sugarcane plantations. On the mainland, Chinese also worked as small merchants, domestics, farmers, grocers, and starting in 1865, as railroad workers on the famous Transcontinental Railroad project.

However, the anti-immigrant and anti-Chinese nativist movement of the late 1800s, best represented by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, forced the Chinese to retreat into their own isolated communities as a matter of survival. Inside these early Chinatowns, the tradition of small business ownership developed as many Chinese provided services to other Chinese and increasingly, to non-Chinese, such as restaurants, laundry, and merchandise retailers. In an effort to avoid having to settle for lower-status or lower-paying jobs in the conventional labor market, some Asian Americans began working for themselves often starting a business and hiring family and friends as cheap labor sources. Businesses that served Asian American communities were able to achieve some success thank to co-ethnic patronage.

Persistent Glass Ceiling Barriers

As the statistics show, many Asian Americans have attained skilled, prestigious, and relatively high-paying professional jobs. At the same time, many still face numerous challenges in their work environments. For example, although Asian Americans have the highest rates of having a college (43% of all adults between 25 and 64) or a law, medicine, or doctorate degree (6.5% of all adults between 25 and 64), they only have the second highest median personal (per capita) income behind that for white workers.

That is, within many occupations, Asian Americans are still paid less than whites, despite having the same educational credentials and years of job experiences. In addition, numerous studies continue to point out that Asian Americans are still underrepresented as senior executives in large publicly-owned corporations.

Many scholars point out that the relative lack of Asian Americans within the most prestigious occupations is due to the continuing presence of a glass ceiling (a "bamboo ceiling" in the case of Asian Americans) within the workplace, meaning that one's success hits an invisible barrier. There are several glass ceiling mechanisms that affect Asian Americans. The first is that many companies consciously or unconsciously bypass Asian Americans when it comes to recruiting for and outreaching to future executives. This may be based on the implicit assumption that Asian Americans do not fit their picture of a future executive or corporate leader.

The Family

One of the most public manifestations of race is the choice of one's partner or spouse. This very individual and personal aspect can sometimes produce a lot of public discussion. Studies consistently show that Asian Americans have some of the highest "intermarriage" (also known as "outmarriage") rates among racial/ethnic minorities -- marrying someone else outside of their own ethnic group. But as always, there's more to the story than just the headline.

The Public and Private Sides of Ethnicity

Whether it's dating or marrying someone of a different race, interracial relationships are not a new phenomenon among Asian Americans. When the first Filipino and Chinese workers came to the U.S. in the 1700s and 1800s, they were almost exclusively men. A few of them eventually married women in the U.S. who were not Asian. However, many people soon saw Asian intermarriage with whites as a threat to American society. Therefore, anti-miscegenation laws (discussed earlier in Chapter 1.4) were passed that prohibited Asians from marrying whites.

History shows that these anti-miscegenation laws were very common in the U.S. They were first passed in the 1600s to prevent freed Black slaves from marrying whites and the biracial children of white slave owners and African slaves from inheriting property. It was not until 1967, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Loving v. Virginia case that such laws were unconstitutional. At that time, 38 states in the U.S. had formal laws on their books that prohibited non-whites from marrying whites. As such, one could argue that it's only been in recent years that interracial marriages have become common in American society (Wong, 2015).

Of course, anti-miscegenation laws were part of a larger anti-Asian movement that eventually led to the Page Law of 1875 that effectively almost eliminated Chinese women from immigrating ot the U.S., the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, and other restrictive regulations. These laws actually made the situation worse because Asian men were no longer able to bring their wives over to the U.S. So in a way, those who wanted to become married had no other choice but to socialize with non-Asians (Pascoe, 2010).

After World War II however, the gender dynamics of this interracial process flip-flopped. U.S. servicemen who fought and were stationed overseas in Asian countries began coming home with Asian "war brides." Data show that from 1945 into the 1970s, thousands of young women from China, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and later Vietnam came to the U.S. as war brides each year. Further, after the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act, many of these Asian war brides eventually helped to expand the Asian American community by sponsoring their family and other relatives to immigrate to the U.S. (Koshy, 2005).

Contributors and Attributions

- Tsuhako, Joy. (Cerritos College)

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College).

- Asian Nation (Le) (CC BY-NC-ND) adapted with permission

Works Cited & Recommended for Further Reading

- Aoki, A., Lien, P. (Eds.). (2020). Asian Pacific American Politics: Celebrating the Scholarly Legacy of Don T. Nakanishi. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chin, M.M. (2020). Stuck: Why Asian Americans Don’t Reach the Top of the Corporate Ladder. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Chou, R.S. & Feagin, J.R. (2008.) The Myth of the Model Minority: Asian Americans Facing Racism. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Constable, N. (2003). Romance on a Global Stage: Pen Pals, Virtual Ethnography, and "Mail Order" Marriages. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Fong, T.P. (2020). The Contemporary Asian American Experience: Beyond the Model Minority (3rd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hartlep, N.D. & Porfilio, B.J. (Eds.). (2015). Killing the Model Minority Stereotype: Asian American Counterstories and Complicity. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Hsu, M.Y. (2017). The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Koshy, S. (2005). Sexual Naturalization: Asian Americans and Miscegenation. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press

- Liu, B. (Ed.). (2017). Solving the Mystery of the Model Minority: The Journey of Asian Americans in America. New York, NY: Cognella Academic Publishing.

- Liu, M. & Lai, T. (2008). The Snake Dance of Asian American Activism: Community, Vision, and Power. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Koshy, S. (2005). Sexual Naturalization: Asian Americans and Miscegenation. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press

- Maeda, D.J. (2011). Rethinking the Asian American Movement. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Nemoto, K. (2009). Racing Romance: Love, Power, and Desire Among Asian American/White Couples. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Okamoto, D.G. (2014). Redefining Race: Asian American Panethnicity and Shifting Ethnic Boundaries. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Osuji, C.K. (2019). Boundaries of Love: Interracial Marriage and the Meaning of Race. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Pascoe, P. (2010). What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Prasso, S. (2010). The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. New York, NY: Public Affairs Publishing.

- Shimizu, C. (2007). The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/American Women on Screen and Scene. Duke University Press.

- Thai, H.C. (2008). For Better or For Worse: Vietnamese International Marriages in the New Global Economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Ty, E. (2017). Asianfail: Narratives of Disenchantment and the Model Minority. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Wong, E.L. (2015). Racial Reconstruction: Black Inclusion, Chinese Exclusion, and the Fictions of Citizenship. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Wong, J., Ramakrishnan, S.K., Lee, T., & Junn, J. (2011). Asian American Political Participation: Emerging Constituents and Their Political Identities. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Wu, C. (2018). Sticky Rice: A Politics of Intraracial Desire. Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Wu, E. (2013). The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.