Anti-Asian Racism & Violence

Ever since the first Asians arrived in America, there has been anti-Asian racism. This includes prejudice and acts of discrimination. For more than 200 years, Asian Americans have been denied equal rights, subjected to harassment and hostility, had their rights revoked and imprisoned for no justifiable reason, physically attacked, and murdered.

Ethnic Competition Leads to Violence

As the section on Asian American history discussed, numerous acts of discrimination against Chinese immigrants culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. For the first and so far only time in American history, an entire ethnic group was singled out and forbidden to step foot on American soil. Although this was not the first such anti-Asian incident, it symbolizes the legacy of racism directed against our community.

It was followed by numerous denials of justice against Chinese and Japanese immigrants seeking to claim equal treatment to land ownership, citizenship, and other rights in state and federal court in the early 1900s. Many times, Asians were not even allowed to testify in court. Perhaps the most infamous episode of anti-Asian racism was the unjustified imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II -- done solely on the basis of their ethnic ancestry.

It seems that whenever there are problems in American society, political or economic, there always seems to be the need for a scapegoat -- someone or a group of people who is/are singled out, unjustifiably blamed, and targeted with severe hostility. Combined with the cultural stereotype of Asian Americans as quiet, weak, and powerless, more and more Asian Americans are victimized, solely on the basis of being an Asian American.

License to Commit Murder = $3,700

Perhaps the most graphic and shocking incident that illustrates this process was the murder of Vincent Chin in 1982. Vincent was beaten to death by two white men (Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz) who called him a "jap" (even though he was Chinese American) and blamed him and Japanese automakers for the current recession and the fact that they were about to lose their jobs. After a brief scuffle inside a local bar/night club, Vincent tried to run for his life until he was cornered nearby, held down by Nitz while Ebens repeatedly smashed his skull and bludgeoned him to death with a baseball bat.

The equally tragic part of this murder were how Vincent's murderers were handled by the criminal justice system. First, instead of being put on trial for second degree murder (intentionally killing someone but without premeditation), the prosecutor instead negotiated a plea bargain for reduced charges of manslaughter (accidentally killing someone). Second, the judge in the case sentenced each man to only two years probation and a $3,700 fine -- absolutely no jail time at all.

The judge defended these sentences by stating that his job was to fit the punishment not just to the crime, but also to the perpetrators. In this case, as he argued, both Ebens and Nitz had no prior criminal record and were both employed at the time of the incident. Therefore, the judge reasoned that neither man represented a threat to society. However, others had a different interpretation of the light sentences. They argued that what the judge was basically saying was that as long as you have no prior criminal record and have a job, you could buy a license to commit murder for $3,700.

This verdict and sentence outraged the entire Asian American community in the Detroit area and all around the country. Soon, several organizations formed a multi-racial coalition to demand justice for the murder of Vincent Chin. They persuaded the U.S. Justice Department to charge the two men with violating Vincent Chin's civil rights. They organized rallies and protests, circulated petitions, and kept the issue in the media spotlight. As one Asian American pointed out, "You can kill a dog and get 30 days in jail, 90 days for a traffic ticket." Vincent's murder was another example of how the life of an Asian American is systematically devalued in relation to that of a "real" American.

The Formation of Solidarity

Although justice was not served in this case, Vincent's murder galvanized the entire Asian American community like no other incident before it. As an example of pluralism/multiculturalism, it resulted in the formation of numerous Asian American community organizations and coalitions whose purpose was to monitor how Asian Americans were treated and to mobilize any and all resources available to fight for justice. Asian Americans saw firsthand how anti-Asian prejudice and hostility operated, both at the personal physical level and at the institutional level.

Since then, groups have documented numerous incidents of hate crimes committed against Asian Americans. NAPALC's 1999 Audit of Violence Against Asian Pacific Americans points out that there was a 13% increase of reported anti-Asian incidents between 1998 and 1999. It found that South Asians were the most targeted among Asian Americans and that vandalism was the most common form of anti-Asian discrimination. This is reinforced by recent anti-Asian vandalism at Stanford University that included such threats as "rape all oriental bitches," "kill all gooks," and "I'm a real white american." Similar incidents and anti-Asian threats have also occurred and continue to occur at college campuses all around the country.

Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Redux: The COVID-19 Situation

In early 2020, reports started circulating about a new infectious respiratory disease that seems to have originated in Wuhan, China. Similar in nature to previous "Severe acute respiratory syndromes," this strain eventually became known as COVID-19, also referred to as the "Coronavirus." Eventually, COVID-19 became a pandemic that has spread around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in widespread racist and xenophobic rhetoric (such as using terms like "Chinese virus," "Wuhan virus," or "Kung-flu"), along with mis/disinformation, and conspiracy theories spread through various media outlets. In turn, these have led to suspicion, hostility, hate, and even violence against anyone perceived to be Chinese or more generally, Asian, Pacific Islander and/or Asian American.

From March of 2020-March of 2021 there were over 3,000 self-reported instances of anti-Asian violence including stabbings, beatings, verbal harassment, bullying and being spit on. Of course being spit on is offensive enough, but during a global pandemic that spreads mostly through droplets, it can also be deadly (Lee and Huang, 2021). These hateful acts have forced Asian Americans into a constant state of hyper-awareness and vigilance when they are in public, taking a huge emotional toll. According to Jennifer Lee and Tiffany Huang (2021), the 2020 Asian American Voter Survey indicated that more than three out of four Asian Americans are concerned about harassment, discrimination, and hate crimes due to COVID-19.

Sadly, these forms of anti-Asian prejudice and discrimination are part of a longer history of racist and xenophobic "Yellow Peril" stereotypes that associate Asians, especially Chinese, and Asian Americans with disease and more generally, being economic, cultural, and/or physical threats to U.S. society. These forms of ignorance and bigotry have been targeted at people of Asian descent in the U.S. for over 150 years. They flare up whenever the U.S. faces any kind of crisis that involves China or some other Asian country, and are exacerbated by political leaders who seek to scapegoat Asians and/or Asian Americans as a way to misdirect anxiety during such times and whose actions implicitly or explicitly embolden acts of anti-Asian hate.

AAPI Activism

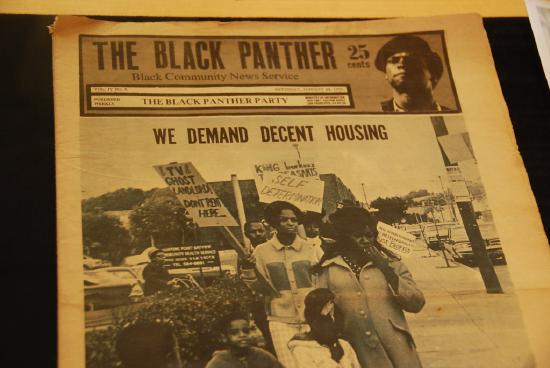

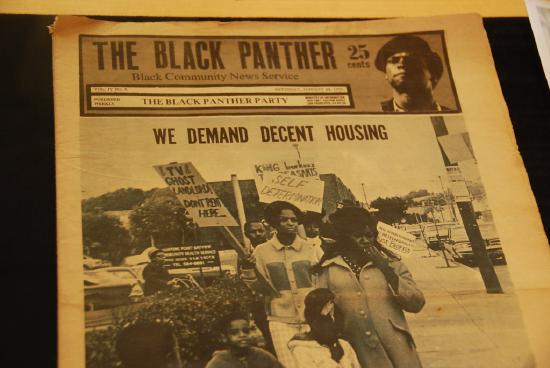

One pattern noted earlier is that of the formation of Asian American ethnic enclaves. These became the central gathering spaces for Asian American activists in the 1960s. Following World War II, Asian American enclaves, which are predominantly near urban centers, faced displacement by corporate interests and local governments through the enactment of "redevelopment zones." Not unlike the contemporary struggles against gentrification (the process of changing a neighborhood to become more affluent and white) happening in predominantly communities of color today, local governments exercised eminent domain which resulted in the forcing out of residents and small businesses to make way for capital investment, especially in downtown areas in big cities across the country such as San Francisco, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Los Angeles.

This displacement of the poor, elderly, and working class immigrants helped give rise to the Asian American Movement (AAM) (Liu & Geron, 2008). Though the AAM would become most known for its opposition to the Vietnam War, its anti-imperialist advocacy, and organizing for racial justice to support other communities of color, the first issues it organized around related to the needs of the enclaves' working class residents such as the implementation of service programs and the protection of affordable housing. As Liu & Geron note, "In casting much of its lot with the interests of these communities and the residential population of workers, shopkeepers, street youth, and elderly, the Asian American Movement built, educated, and significantly defined itself" (2008, p. 23).

Pan-Asianism & Black Power

Beyond the enclave-based organizing efforts, what differentiated the AAM from previous Asian American activists was its emphasis on pan-Asianism which is an ideology that promotes the political and economic unity and cooperation of Asian peoples.

In fact, one of AAM's notable achievements is the creation of the term "Asian American" which includes the myriad Asian ethnic groups who have migrated to the United States. While the recognition of Asian Americans as a group has its value for political organizing efforts and as a label of self-determination, as has been discussed in other parts of this chapter, it can also reinforce the stereotype that all Asians are the same. Though the identity of "Asian American" is rarely self-ascribed (people tend to say they are "Japanese American," "Korean American," "Thai," etc.) the term, coined by Berkeley students Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee, was originally inspired by the Black Power Movement and as a way to unite Japanese, Chinese and Filipino American students on campus under the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) formed in 1968 (Maeda, 2016).

The pan-Asian ideology also included a transnational solidarity with people of color around the world impacted by U.S. neo-imperialism. Similarly, on the East Coast, two leftist Nisei (second-generation Japanese) women, Kazu Iijima and Minn Masuda, saw the anti-racist and anti-imperialist values promoted by Black Power as the antidote to the pro-assimilationist sentiment that developed in the Japanese American community following their experiences with being interned in concentration camps during World War II (Maeda, 2016).

Asian Women's Organizing

Another similarity between the Black Power and the AAM was the sidelining of women's issues and the lack of women in leadership positions.

Though the fundamental concerns of social justice, equity and human rights are just as much women's issues as they are men's issues, the patriarchal cultural dynamics often pushed Asian women's concerns to auxiliary groups. The change in immigration laws facilitated the migration of highly educated and affluent Asian immigrants after 1965 also gave rise to the formation of large, primarily middle-class East Asian women's organizations. These groups received more support from conservative and mainstream institutions since they focused on education and service projects rather than the radical, leftist organizing found in the AAM. This distinction contributed to the perpetuation of the model minority myth by implying that, "there was a 'good' minority in tacit opposition to the 'bad' minorities -- African Americans and Latinos" (Shah, 1997).

Not only were Asian women sidelined in the AAM, but they were have also been marginalized in the women's movement.

Mitsuye Yamada, author of “Asian Pacific American Women and Feminism,” writes about the disappointment and invisibility many Asian Pacific American women have felt towards the women’s movement. Issues important to Euro American feminists have not always included issues important to and perspectives of Asian Pacific American women. Yamada examines that women of color are often made to feel they have to choose between ethnicity and gender, and she argues the two are not at war with each other, so Asian Pacific American women should not have to choose one or the other. Barbara Ryan, author of Identity Politics in the Women's Movement, quotes Yamada:

Asian Pacific American women will not speak out to say what we have on our minds until we feel secure within ourselves that this is our home too, and until our white sisters indicate by their actions that they want to join us in our struggle because it is theirs also...We need to raise our voices a little more, even as they say to us ‘This is so uncharacteristic of you.’ To fully recognize our own invisibility is to finally be on the path towards visibility.

Millenial Amanda Nguyen, a civil rights activist and founder of RISE, a non-profit organization protecting the rights of sexual assault victims, has raised her voice to call attention to and make visible the violence against the AAPI community. Nguyen exercised her agency through her Instagram social media post in February 2021 which attracted more than 3 million views within 24 hours. In her post, she called out the anti-Asian backlash and increase of hate crimes (150% increase nationwide!) affecting AAPI communities in the U.S in 2020 and 2021, which has been virtually ignored by the mainstream press. In turn, Nguyen's activism has caused the mainstream media to cover Nguyen's plea for voices and issues of the AAPI community to be raised.

Contributors and Attributions

- Tsuhako, Joy. (Cerritos College)

- Gutierrez, Erika. (Santiago Canyon College)

Works Cited

- Dong, H. (2010). International Hotels Final Victory: International Hotel Senior Housing, Inc.

- Filipino Migration Center. (n.d.). Stop Labor Trafficking! End forced migration!

- Khmer Girls in Action. (2020). Campaigns.

- Liu, M., & Geron, K. (2008). Changing neighborhood: ethnic enclaves and the struggle for social justice. Social Justice, 35(2), 18–35.

- Maeda, D. (2016). The Asian American movement. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History.

- Ryan, B. (2001). Identity Politics in the Women's Movement. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Shah, S. (Ed.). (1999). Dragon Ladies: Asian American Feminists Breathe Fire. Boston, MA: South End Press.

- Solomon, L. (1998). "No evictions: we won't move!" the struggle to save the i-hotel. Roots of Justice: Stories of Organizing in Communities of Color. Berkeley, CA: Chardon Press: 93-104.

- Trask, H. (March 2000). The struggle for hawaiian sovereignty - introduction. Cultural Survival. 24(1).