5: Our Story - Asian Americans

- Page ID

- 145351

At the end of this module, students will be able to:

- describe the typical immigration patterns of Asians throughout U.S. history

- identify key legislation that prevented Asians from migrating to America and accessing the naturalization process

- explore the various forms of xenophobic behavior of Americans regarding Asian immigrants

- explain the civil rights efforts of the Asian American communities during the 1960s and 1970s

- assess how globalism and warfare of the 20th century impacted Asian Americans and Asian refugees in America

- explore the issues of the late 20th and early 21st century and how they have impacted Asian Americans

KEY TERMS & CONCEPTS

|

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 Chinese Massacre of 1871 COVID-19 Executive Order 9066 Gold Rush Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 Japanese Internment Model Minority Ozawa v. U.S. (1922) Page Act |

Pull Factor Push Factor Snake River Massacre Stockton School Shooting Thind v. U.S. (1923) U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) Vincent Chin Yellow Power Xenophobia |

INTRODUCTION

Many Americans have little to no knowledge about the role of Asian Americans in this nation’s history. Their stories are usually left out of history books with brief mention of internment camps, WWII, and Vietnam. This oversight has occurred for two reasons. First, Asia is a vast continent that has supplied the most diverse population of American immigrants over the course of our history. To cover the history of all these immigrants would prove quite difficult in most high school or college courses. Secondly, most history books used in public schools and colleges offer little coverage of the role of Asian Americans in U.S. history. For many years, it was believed that Asian Americans had little impact in America. This is false.

From China to India to the Philippines, Asians have been migrating to the U.S. in ebbs and flows since about the 19th century. Like many other immigrant groups, specifically non-Whites, Asians were largely unaccepted and at times even met with aggression by American society. Like many non-White immigrants, Asians were used for difficult, sometime dangerous labor, but cast aside as inferior and unable to enter the fold of American society. Asian immigrants faced numerous legal obstacles from entry to the country, to access to citizenship, to general social acceptance.

When studying Asian American history, it is useful to break up the history into multiple blocks of time. Like many other diverse ethnic groups, there is not one solitary wave of immigration that occurred with Asians.

We will be focusing our study of Asian Americans in three waves: the arrival of large numbers of East Asians during the American Gold Rush, aspects of mid-20th century global conflicts, and the wave of immigration that shifted the American demographic during the mid-1960s. During each of these times, the Asians were met with much adversity, but many still managed to prosper in America despite it.

This is their story.

MID 1800S TO EARLY 20TH CENTURY

Europeans have had a long-held fascination with the far East due to medieval travelers and traders like Marco Polo. For much of the early modern period, Spanish and Portuguese sailors attempted to find new trade routes to access the highly coveted exotic goods of the east. By the mid-16th century, Spanish explorers had much contact with Asians, and even employed some from their colonizing efforts in places like the Philippines. The earliest Asian arrivals to the North America were Filipino crew amongst the Spanish ships that landed in Northern California in the year 1587 (Lee, 2015). Due to Spanish colonization of the Americas, a mixture of Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino peoples migrated to South America during this era. Although Asians arrived with the Spanish, generally they were treated with much derision: paid less than Spanish sailors aboard these ships, given substandard living conditions and provisions.

By the early 19th century, a significant number of Asian immigrants, mostly Chinese, arrived in America. The motivation for migration was due to a variety of reasons, reasons that are called push and pull factors. A push factor would be something that compels an individual or group to leave a country, such as a political upheaval or armed conflict. A pull factor is a reason that would compel a person or group to enter a country, such as economic opportunity. The primary opportunity during this time for the Chinese to migrate to America was the Gold Rush.

The Gold Rush began when a new settler to California named James Marshall found a shiny substance in a riverbed in the year 1848. Thereafter, the scramble to pan and mine for gold became a global pull factor. Immigrants flocked from around the world and the U.S. to benefit from this discovery including many Chinese. Named for the year at the height of this rush, the “49ers” established towns, businesses, and laws to support this influx of people. Asian immigrants that made landfall on the west coast came in droves, but they faced obstacles linked to their countries of origin. Racial discrimination made it difficult to capitalize on the success of gold mining and panning, compared to other Americans and White immigrants.

The Chinese men who immigrated were immediately “othered” for their appearance. Many of them had a haircut called a que, which had a hairline shaved halfway up their scalps and worn in a long ponytail in the back. They wore clothes that appeared to be cotton pajamas to Americans, and they ate food with sticks (chopsticks) and strange sauces. These men were labeled “celestials” to complete their perception of strange and untrustworthiness. Lee Chew recounted the treatment of Chinese immigrants like himself, calling it “wrong and mean,” and that Chinese men were used only for “cheap labor.” Chew compared himself to other immigrants of the time like the Irish and Italians, and how the Chinese were unfairly denied citizenship or belonging as “law abiding, patriotic Americans” (Chew, 1882).

The start of the Gold Rush occurred when California was not yet annexed as a state, meaning it had no political officials, state constitution, or organized law enforcement. This was the “wild west,” and local sheriffs and deputies were often stretched thin, and law was enforced haphazardly. Venerable groups like the Chinese were offered little protection during this tenuous time, and these “celestials” were received with fear and hatred. This type of behavior is called xenophobia, a fear or hatred of foreigners. Often, this behavior erupted into violence upon the immigrant groups.

This tension would come to a head in events like the Chinese Massacre of 1871. Americans’ xenophobia led them to resort to violence to discourage the Chinese from settling permanently in America. Protests erupted in many cities to drive out these immigrants. In Los Angeles, tensions escalated into violence when Chinese men were accused to have killed two White men in the city, one of them a police officer. Chinese men were openly stalked and killed, resulting in 19 dead, and 15 later lynched by hanging.

Another instance of xenophobia were the events of the Snake River Massacre of 1887 when two small groups of Chinese men obtained mining permits in Oregon. White men conspired to attack these men, tracking them through the Oregon hills and systematically murdering them. An accurate number of the men killed is unknown since their bodies were left to the elements for an extended period and their gold stolen. The White perpetrators were brought to trial and later acquitted. This violent event was one of many that exhibits open violence against Asians with little to no consequences.

Despite having little success in gold mining, the Chinese found other ways to make a living in the U.S. In the 1860s, the Chinese found work mostly in the construction of railroads. These men did the most difficult and dangerous work, blasting rock with dynamite, clearing away the debris, shoveling and more. The achievement of the transcontinental railroad helped build the wealth of the U.S. during the 19th century, and 90 percent of its work was done by Chinese immigrants. When the railroad was completed in 1869, not one Chinese worker was present in the picture to commemorate the completion (Lee, 2015).

After much violence and conflict, Americans were ready to solidify their discrimination into legislation. Beginning in the 1860s, many laws were passed at local and state levels to prevent Asian immigrants from economic advancement. This eventually led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a piece of legislation that would prevent Chinese immigrants from entering the US for 10 years unless entering for temporary stays related to business or education. The Chinese were also banned from obtaining naturalized citizenship, a law that would be challenged later.

Perhaps even more damaging was the Page Act, passed in 1875, which banned Asian women from entering the country because they were suspected of prostitution. This act had two ramifications. First, there was the implication that Asian women were suspected of sex work or corruption of society with promiscuity. Many lawmakers and others argued frequently at the time that both Asian men and women posed a sexual danger to American society. Secondly, it was very common for men to immigrate first, then send for the rest of their families. If wives attempted to enter the country after their husbands settled in the U.S., they faced an additional obstacle of being suspected of prostitution upon entry. Therefore, families were prevented from uniting as a result of this act, and Chinese women were blanketed with the label of promiscuity and sexual deviancy.

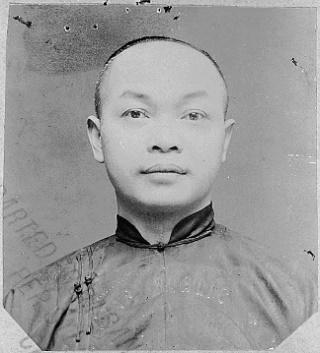

The Asians that were already in the country were treated with hostility and suspiciousness. The first picture identification cards were carried by the Chinese to identify them as foreign. Law makers in America then wondered, where do the Chinese and other Asians “fit” in society? Should they be Americanized, assimilated, or educated?

Asian immigrants and Asian Americans tried to fit in, acclimate to American society, and “become” American in a variety of ways. Methods included learning English, changing clothing and cultural practices, marrying Americans, and more. Most importantly, Asian Americans worked within the court systems in the U.S. to assert their civil rights. The following three cases illustrate some key court battles.

U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)

Wong Kim Ark was an American born Chinese man. His parents were born in China, but Ark was from California. In 1894, Ark took a trip to China to visit, and when he attempted to return to his home in San Francisco, he was denied entry. Officials in California denied his citizenship because his parents were ineligible for naturalization under Chinese exclusionary policies. After Ark’s case was tried before the U.S. Supreme Court, the fourteenth amendment was upheld, granting Ark birthright citizenship as being a native-born citizen. Ark’s case was monumental and would serve as a precedent for birthright citizenship, regardless of race from that point onward.

Ozawa v. U.S. (1922)

In the year 1922, one Japanese man decided to challenge the legality of Asian immigrants being barred from the naturalization process and American definitions of race. Takao Ozawa sought to claim his rights and access to the American dream by attempting naturalization. Ozawa felt entitled to the right, mainly by the basis of his success, contributions to society, and efforts to Americanize. The most interesting argument was the color of his skin. It appeared “White” just like many other American citizens. Ozawa attempted assimilation much like Italians and Irish had in his recent past. He said, “I am not American, but at heart I am a true American.” However, the courts declared against him, and the country would not see Japanese immigrants achieve citizenship for many years after.

Thind v. U.S. (1923)

Bhagat Singh Thind was a high caste Indian man who arrived in America to attend university. He served in the U.S. army during WWI and attempted to obtain citizenship. His naturalization process was denied, on the basis of his “Hindu” status, despite the fact that he was Sikh. Thind sued, on the basis that he was, in fact, Caucasian. This logic follows the anthropological distinction that classified Thind as Caucasian, since his ancestors descended from the Caucus mountains. The court ruled against him, and his citizenship was revoked, along with other East Indians that had previously been granted citizenship.

As a result of this case, many other “non-White” persons lost their citizenship. One of those men was Vaishno Das Bagai. He escaped British tyranny in India and established a successful business in San Francisco. He received his citizenship in 1921, only later to have it revoked after the Thind ruling. Bagai took his own life in 1928 and his suicide note was published in the newspaper.

His words - “I came to America thinking, dreaming and hoping to make this land my home…But now they come to me and say, I am no longer an American citizen…Humility and insults, who is responsible for all this? Myself and the American government. I do not choose to live the life of an interned person: yes, I am in a free country and can move about where and when I wish inside the country. Is life worth living in a gilded cage?”

These three court cases prove that Asian Americans were continually denied a place in American society, despite military service, economic status, or willingness to adapt to society. This precedent continued into the later 20th century; even as American society diversified even further.

GLOBAL CONFLICTS & THE 20TH CENTURY

As the U.S. propelled into the new century, so did their involvement in global affairs. We begin at the turn of the century wherein many industrialized countries were participating in “new imperialism,” efforts of colonization and imperialism in non-White countries. The U.S. was involved in armed conflicts in the western hemisphere like the Spanish-American War which ended in 1898 with U.S. control over Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Freedom fighters led by Filipino nationalist Emilio Aguinaldo rejected U.S. sovereignty having fought side by side their American allies against the Spanish. This rejection prolonged the war, now fought between the U.S. and Filipinos until 1902.

Colonization of the Philippines was characterized by President McKinley and other lawmakers as a boon to Filipinos who were believed to be too uncivilized and savage for self-rule. It was these same principles that continued to prevail foreign policy throughout most of the first half of the 20th century.

World wars during the 20th century brought Americans together with an abundance of national pride and duty to the country. At times, war also evoked feelings of anxiety and xenophobia to the nations involved in the conflict. World War II is one of those times.

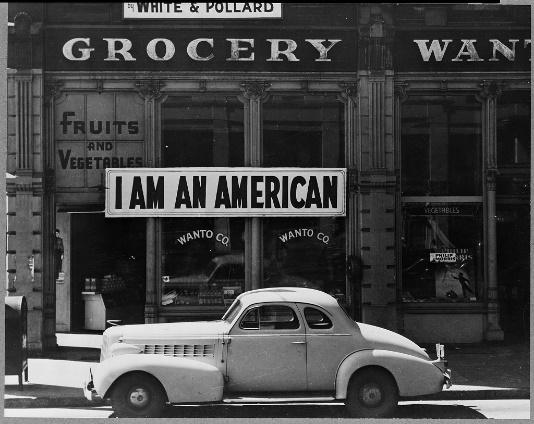

Just before the winter of 1941, there were about 125,000 people of Japanese descent living in America, most of them in west coast regions. Pearl Harbor was a U.S. naval station in Hawaii that was the victim of a surprise attack by the Japanese on December 7, 1941. This attack resulted in mass American casualties and was too close to the mainland for officials. As a result, Americans stepped up their involvement in the war, and in February of 1942, President Roosevelt issued the Executive Order 9066. This order authorized the militarized internment of all “persons of Japanese ancestry” residing in the western regions of the U.S. The justification was that Americans suspected that anyone of Japanese ancestry could still have loyalties to their ethnic homelands and would practice espionage. There was little to no evidence to support this concept, nevertheless, many supported this order and about 110,000 Japanese, many of them citizens and American born, many of them children, were put into internment camps.

Forced internment caused almost $2 billion in property loss and even more in income loss for those interned. Internment lasted until the end of the war, and some even remained in the camps post-war because they no longer had homes to return to, for they were repossessed by authorities. It was not until the 1980s when the U.S. government paid restitution to the families that were affected in the amount of $20,000 per Japanese American families that were interned.

NEW IMMIGRANTS & EXPANSION OF DIVERSITY

The end of World War II brought the U.S. a new role on the global stage. The use of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end the war made the U.S. the most powerful country in the world, while also causing mass death and destruction in the name of democracy. The paradox of these two concepts conveyed a conflict in American ideology.

In order to maintain the moral high ground, the U.S. passed new immigration policies in 1952, revising earlier immigration quotas of the 1920s. This act loosened some restrictions on Asian nations to immigrate to the U.S., and also made naturalization possible for Japanese, Korean, and Chinese immigrants, but only from these countries of origin.

The next decade brought milestones for racial minorities. These changes included legislation, social movements, and community activism that remade Asian Americans for the next few decades.

First, the legislation that passed broadened the definition of Asian American and dramatically diversified America. This was the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, also referred to as the Hart-Cellar Act. The act overturned previous legislation that granted entry into the country based on national origin. Instead, the act created preference for highly skilled immigrants and ones that already had family in the country. Policymakers did not anticipate the impact of this legislation. Immigration rates increased dramatically, and many of those immigrants came from Asian countries.

Next, as the Civil Rights movement propelled equality forward for African Americans, the same call for equality was inspired in many other groups. Asian Americans took to the streets just as other racially minoritized groups demanding for equality. Asian Americans like Grace Lee Boggs participated in marches for equality on behalf of African Americans, then turned to inspire Asian communities to do the same. Philip Vera Cruz was a Filipino American who was active in promote fair labor practices for farmers in California and was instrumental in Cesar Chavez’s protest movements in Delano, California. Asian Americans formed a pan-Asian coalition nationwide of Asians that would reject discriminatory labels like “Oriental” and “yellow,” and demand equality on all fronts for Asian Americans. Like many other minoritized groups, in an effort to reclaim a once derogatory term, supporters of Asian American rights claimed Yellow Power in their rhetoric.

Although the label of “Oriental” is now largely understood as inappropriate, another more nefarious label was applied to the Asian community, one that has very complex ramifications. This is the label of “model minority.” The concept of the model minority characterizes Asians as obedient, law-abiding, and submissive to authorities (Thrupkaew, 2002). It also uses three types of Asians, the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean as prime examples of what a successful immigrant should be. These three groups have had their hardships but have been able to become successful in the U.S. and statistically held jobs with higher wages and did not rely on government programs. This concept created much tension between minority groups as well as within the Asian community itself.

First, the model minority paradigm was created to juxtapose the perceived success of Asians against the perceived failures of other persons of color like African Americans and Hispanic Americans who were reliant of government programs and assistance at higher rates. By upholding the Asian community as “model minorities,” the accusation on other ethnic groups was a questioning on why they also could not live up to those standards.

Secondly, the model minority term created tensions between Asian Americans. Japanese, Korean, and Chinese immigrants had a longer history of emigrating into the U.S., and as a result were second and third or more generations of wealth by this point. Additionally, by the 1950s, preference was given to highly skilled Asians who were of these three groups to enter the country, providing a solid economic foundation from the start. And lastly, these three groups reflect a clear bias of colorism, for decedents from these groups tend to be lighter complected than newer immigrants and refugees post 1965. All of these factors created tension and resentment between Asians who either benefitted from the label or were disadvantaged as a model minority.

Although the 1960s brought a push for social change in America, equality continued to be an uphill battle for Asian Americans. Further social conflicts around the globe like the Vietnam War and human rights crises brought even more Asians into the U.S., but this time as refugees. Southeast Asian groups like Vietnamese, Laos, Cambodian, and Hmong immigrants came to the U.S. and were received with fear and suspicion that heightened tensions in some pockets of the nation. Waves of new immigrants typically bring fears to Americans who anticipate a strain on resources that directly affect their livelihoods. These tensions will sometimes erupt in violence as they did in two separate cases during the 1980s.

The 1980s brought an economic downturn that inflated the sense of limited community resources and employment. This anxiety is best exemplified with the murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese man who lived in Detroit, Michigan. Economic strain was felt in blue collar jobs in this city, mainly the automobile industry. Chin was coming home from his bachelor party when he was beaten to death by two White men who claimed he was a “Jap” that was taking jobs away from Americans. These men plead guilty, but received no jail time, only probation with a $3,000 fine.

In Stockton, California, at the end of the decade, 1989, another heinous act motivated by racism occurred. This Stockton school shooting marked the deadliest school shooting with the highest number of fatalities and injuries until Columbine in 1999. A White man used an AK-47 to enter Cleveland Elementary School of predominantly Asian American children and opened fire. He shot 34 people and killed 5 that were between the ages of 6 and 9. This elementary school was known to have been attended by mostly Asian students, many of them refugees from Southeast Asia. Of those children killed, all of them were Asian.

THE RECENT PAST

By the 21st century, bias and discrimination continued as a result of the historical racial discrimination of the previous decades. The model minority myth continues to be the way in which most Americans view the Asian American community. While there is some truth to the success of select Asian American groups that reside in the U.S., still many reportedly experience racial discrimination and hate crimes even to this day.

By 2020, a global pandemic made the fears and anxieties of many Americans manifest in different ways, amplified, and proliferated by the internet and social media. Known as COVID-19, the virus that is believed to have originated in China has affected the Asian American community in terrible ways. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI) have reported countless acts of violence against Asians every day. These acts of violence range from calling names, spitting in faces, to physical violence reigned down mostly on the elderly.

Perhaps one of the more significant acts of violence occurred in Atlanta, Georgia in 2021. This incident involved a White man entering into a spa and shooting at its occupants. Eight people were killed, six of them Asian women. The shooting was the alleged result of the shooters Christian faith at odds with his sex addiction. However, the shooting exemplified another incident of anti-Asian sentiment following the tensions of the pandemic. The incident sparked protests in multiple cities against anti-Asian violence that were being reported across the country.

In the 21st century, Asian Americans remain the most ethnically diverse, rapidly growing ethnic groups in America. The Democratic Presidential nominee campaign of Andrew Yang put a prominent Asian at the forefront of American politics. A Korean foreign language film, Parasite, won Best Picture at the Academy Awards with overwhelming praise. These are signals that Asian Americans are not only active and prominent members of society but have even more room to grow in the coming years.

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 5.1

SOUTHEAST ASIAN REFUGEES

When Southeast Asian refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam started to flow into American cities starting in 1976 and into the 1980s, most Americans didn’t know who we were, much less what we had gone through before coming to the United States. In many ways, we were hoping no one would know who we were. Our neighbors thought we were Chinese or Japanese – after all, all Asians look alike to them, and so we must be the same. “Are you Chinese? Are you Japanese?” they asked. We knew English enough to know those questions were about who we were, but we shook our heads, saying, “No, no.” And perhaps we could’ve told our neighbors that we were Hmong, but it would be too difficult to explain why we came to the United States. Silence was the better choice.

Another generation had to be immersed in the English language and culture before we could tell our story. Our story of survival and resilience and collaboration with the U.S. to fight communists simply had to wait. Among first-generation SE Asian college students, we felt the need to capture our own respective lived experiences from our own lenses rather than waiting for another non-SE Asian person to give us another watered-down version of our plight. Young scholars from the Cambodian and Vietnamese communities had already documented their own refugee experiences through various publications in recent years. In my case as a first-generation Hmong college student and now a professor of political science and ethnic studies, I’m compelled to provide my own version of the Hmong plight to the U.S. and secondary migration to the Central California.

Community and social dialogues among Hmong elders revealed that the first few Hmong families to move to the Central Valley, California started in Merced in 1979. From those families, words got around to relatives across the country – wherever resettlement agencies had scattered us (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Ohio, Tennessee, or Oklahoma) – that California’s Central Valley had fertile land for farming, the only method the Hmong had been familiar with in making a living. We came from the mountainous terrains in Laos but found the flat valley attractive, serving as a magnetic device that continued to pull Hmong families across the country to start their new lives in Merced and Fresno. This massive secondary migration of Hmong refugees to the Central Valley caused social workers to accuse the Hmong of taking advantage of the generous California welfare system. In 1985 the welfare dependency among the Hmong was about 75%. Our big families of 6.9 children in 1986 received more welfare cash aid than a father working $4.25 an hour minimum wage job.

Though small in number, Southeast Asians in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam played a pivotal role in the Cold War, international political power jostling between the United States and the Soviet Union. For fifteen years from 1960 – 1975, Americans read in newspapers and saw the disaster of the Vietnam War unfolded on television. The political quagmire that engulfed Southeast Asia expanded over three presidential administrations – Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon - became a permanent scar on the American consciousness, a hefty price to pay both in human lives and money (more than 58,000 dead and over 300,000 wounded and $168 billion - $1 trillion in today’s money.)

In part this American foreign policy (communist containment) in Southeast Asia was the core of the United States’ response to communist expansion in Asia at large. In 1949, China turned communists with Mao Zedong’s victory over the Nationalist Chinese forces. A year later with the support of the Soviet Union and China, communist North Korea invaded democratic South Korea. The conflict ended in an armistice in 1953. In Southeast Asia, the three French colonies Cambodian, Laos, and Vietnam were vying for their respective independence from France beginning in 1945. Subsequently, Cambodia and Laos were granted independence in 1953 without military conflicts. However, France would not relinquish the same to Vietnam until it was militarily defeated at the battle of Dien Bien Phu by the Vietnamese nationalist Viet Minh in 1954. The United States orchestrated the Geneva Accord of 1954 to divide Vietnam into two countries – North Vietnam, communist controlled and South Vietnam, democratic. This strategy of using South Vietnam as a buffer zone to protect Thailand and Burma was part of the “domino theory” hysteria that if one country fell to communists, then the neighboring one will also fall, and then the one after.

Peace in Southeast Asia proved fragile as the power vacuum created by the departure of France resulted in the monarchies in Laos and Cambodia too unstructured to govern. Accusations of corruption and other internal conflicts ensued, creating ideological factions that could not come to political consensus. The Geneva Accord of 1962, an international agreement to establish Cambodia and Laos as neutral countries, meaning they supported neither communism nor democracy, and there were to be no foreign troops in Laos or Cambodia. But this agreement simply proved its own ineffectiveness. The regional powers like China and North Vietnam and the superpower of the Soviet Union and China never adhered to the terms. North Vietnam infiltrated to Laos and Cambodia through the Ho Chi Minh Trail that cut through eastern Laos, bordering North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Under the Kennedy administration, the CIA secretly recruited democratic leaning Hmong, Lao, and other indigenous hilltribes to fight the North Vietnamese communists on the Trail. Leading this effort was a Hmong man named Vang Pao, also known as General Vang Pao, who rose to prominence as a freedom loving fighter and staunch American ally. The primary duties of the Hmong under his command were to: 1) disrupt the flow of supplies to South Vietnam, 2) rescue downed American pilots, 3) provide strategic intelligence on enemy operations, and 4) guard satellite installations. The Hmong became the sacrificial lamb in America’s secret war to contain communists by paying with 10% of its population in Laos – 30,000 dead among 300,000.

The calamity of American foreign policy in Southeast Asia created one of the largest exoduses of refugees out of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. People who had sided with the American effort were targeted for reprisals by communist forces after the war. About 200,000 Cambodians fled the terror of their own countrymen, the Khmer Rouge, which was responsible for killing over 2 million of its own population. In Laos nearly 300,000 Hmong, lowland Lao, Mien, Khmu, Lahu and other hilltribes made their own escapes to neighboring Thailand. Over a million Vietnamese fled South Vietnam to the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore. This tragedy of constant refugees fleeing persecution continued into the mid 2000’s, but politically speaking, people who fled Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam after 1991 were no longer categorized as refugees.

This story “Southeast Asian Refugees” by Silas Cha is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

SUMMARY

Like previously covered groups, people of Asian descent have been present in the Americas since the 16th century. Peoples from Asia have typically been regarded as perpetually foreign, admired for their exoticism, but devalued as too otherworldly. Asians have struggled to be accepted amongst American society, despite their contributions of labor, military service, and wealth. Even when utilizing the justice system to assert their civil rights, Asians were met with opposition and oppression. Regardless of their rejection, Asian Americans forged a place for themselves in American society, growing in number and influence as one of the most diverse and fast-growing groups in the U.S. today.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- How did people of Asian descent make their way to the Americas during the colonial period?

- How were Asians generally received during the 1800s?

- Explain some of the ways Asians attempted to assimilate into American society?

- What political policies of the 20th century impact Asian Americans?

- What kinds of racial discrimination did Asian Americans endure after WWII?

- How did Asian Americans assert their civil rights during the 1960s and 70s?

TO MY FUTURE SELF

From the module, what information and new knowledge did I find interesting or useful? How do I plan to use this information and new knowledge in my personal and professional development and improvement?

REFERENCES

Fadiman, A. (1997). The spirit catches you and you fall down : a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 1. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 2. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Hamilton-Merritt, J. (1993). Tragic mountains: the Hmong, the Americans, and the secret wars for Laos, 1942-1992. Indiana University Press.

Lee, E. (2015). The making of Asian America: A history. Simon & Schuster.

Locke, J. & Wright, B. (2019). The American yawp. Stanford University Press. http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html.

Rothenberg, P. S. (2016). Race, class, and gender in the United States: An integrated study. (10th ed). Macmillan.

60 Minutes. (2015 August 13). Hmong Our Secret Army. [YouTube]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4U2P7tsOAQ

Takaki, R. (1993). A different mirror: A history of multicultural America. Back Bay Books.