4: Our Story - African Americans

- Page ID

- 145366

At the end of this module, students will be able to:

- describe the transatlantic slave trade and formation of the colonial slave system in North America

- explore the development of the U.S. economy in terms of its reliance and use of slave labor

- identify justification of Black slave labor from the Antebellum period to the Civil War

- examine the effects of the Reconstruction period and the rise of the Lost Cause ideology

- describe the 19th and 20th century development of segregation, Jim Crow laws, and racialized violence

- explain key people and events of the civil rights movement in the 1960s

- explore the issues and impact of the late 20th and early 21st century on African Americans

KEY TERMS & CONCEPTS

|

Abolitionists Abraham Lincoln American Colonization Society Bacon’s Rebellion Booker T. Washington Brown v. Board of Education Civil Rights Act Of 1964 Claudette Colvin Congress of Racial Equity (CORE) Colonization Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dred Scott v. Sanford Emancipation Proclamation Executive Order 8802 Freedom Riders Great Migration Harlem Renaissance Harriet Beecher Stowe Indentured Servants Jim Crow John Rolfe Juneteenth Ku Klux Klan Lost Cause Lynching Manumission |

March on Washington D.C. Massive Resistance Minstrel Shows National Association for The Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Non-Violent Protests Paternalism Plessy v. Ferguson Popular Sovereignty Redlining Rosa Parks Sarah Keyes Separate but Equal Sit-In Protests Slave Codes Slave Resistance Slavery Stono Rebellion Three-Fifths Clause Transatlantic Slave Trade Tulsa Massacre Of 1921 Underground Railroad William Lloyd Garrison Watts Riots Of 1965 W.E.B. Dubois Voting Rights Act |

INTRODUCTION

The history of people of African descent in this country is complex and long, dating back to the foundations of this country. For most of that history, the lives of African Americans have been wrought with oppression and racism, but despite countless barriers, have contributed so much to the nation’s history and its development.

The major events of African American history are best told in different phases – colonial America to 1877, and 1877 to present – similar to how the study of U.S. history is structured in schools. The historical narrative is also broken down into subphases, the Civil Rights era into the 1990s, then the most recent past. This is intentional, since Black history is very much American history, just as most other racial and ethnic groups.

This is their story.

COLONIAL PERIOD TO RECONSTRUCTION

Most historians begin the discussion of Black history in 1619 when the first slaves were sold in Virginia. However, it is more effective to begin this history with the moment when free people of African descent arrived in the Americas. Spanish colonizers arrived with the first free Africans in 1492. Free Blacks existed in the Americas before enslaved ones did.

In North America, the first recorded peoples of African descent arrived in Jamestown in 1619. These men and women were sold by Dutch traders as slave laborers to English settlers. Slavery, the practice of forced labor without pay, was not a practice exclusive to the New World, or even to Europeans. Slave labor had been utilized in many civilizations over the course of human history. However, the system of colonization and the trans-Atlantic trade changed the practice of slave labor for the next few centuries.

Colonial Virginia was in its early stages of development in 1619. When Virginia was settled, the colony struggled with acclimation, starvation, and population growth. But things started to take a turn for the better when John Rolfe brought tobacco planting to the colony. This crop was the colony’s saving grace, for it became the cash crop upon which to build a powerful nation. Tobacco was a difficult crop to harvest. Typically, the arduous labor required for this crop was carried out by indentured servants - poor White contract laborers who obtained their ticket to the new world by signing away 7-10 years of their life to investors in the colonies. But over time, circumstances changed, and the White laborers proved to be problematic, provoking a shift to African slave labor. The change in circumstances including general human progress towards individual freedoms and the need to fulfill goals of opportunity and land ownership that were typical of voluntary transatlantic migrants. In these early colonial times, there were no clear rules as to how to regard Black slaves, nor was the concept of race clearly defined. Generally, there was little regard for people of African descent, and Black slaves were treated as less than human.

In the early 15th century, Portuguese explorers established “slave factories”, or trading centers on the western coasts of Africa, and began exchanging goods with African leaders for slave laborers. Approximately four million Africans were transported and sold from the western coast across the Atlantic for labor, forming the transatlantic slave trade. Slave traders justified their practice of human trafficking by treating these men, women, and children not as human beings, but as chattel, mere commodities to be sold for a profit. Slave ships were outfitted to maximize profits, by chaining up the slaves laying down, side-by-side with little room to move or even breathe. When Olaudah Equiano recalled the Middle Passage, the name for the journey across the Atlantic, he recounted feeling “suffocated,” laying in “filth” and “horror” (Equiano, 1789). Many of the enslaved peoples perished during the long and arduous journey from disease, starvation, or even suicide. Tightly packed in the bowels of ships, Africans were dehumanized, fed only enough to stay alive on the journey across the Atlantic, which could take anywhere from 4 to 8 weeks (Foner, 2020). Many of these individuals were sold into the Caribbean and South America, and only a small percentage would be sold into North America.

As Virginia continued to develop into a successful and lucrative colony due to tobacco, English settlers started to get restless. They wanted to continue to expand westward, but English authorities had signed treaties with nearby Native American tribes preventing them from infringing on their territory. A new settler, Nathaniel Bacon, harnessed the discontent of the White settlers to wage a rebellion against the local leadership spearheaded by William Berkeley. Bacon’s rebellion uncovered many class issues of the colony, including the discontent of poor Whites and former indentured servants. After months of protest and armed conflict, Bacon was dead, his supporters hanged, and Jamestown was burned to the ground. The groups that were the most disadvantaged after the conflict were the Native Americans, whose lands were continually taken away from them, and Black slaves, who would be utilized for labor more heavily than White European settlers, regardless of class.

While Bacon’s rebellion helped define colonial settlers need for manual labor, early slave codes were responsible for definition of people of African descent in the colonies. The earliest colonial years would experience some ambiguity between poor Whites and Black colonists – some colonists even married and had biracial children. But as concepts of race were being further defined by scholars and society in general, Virginia again was at the forefront of creating legal parameters of race relations. Virginia established the first Slave Codes, a list of laws and regulations to define punishments, legal status, and property rights regarding Black slaves. These codes were most likely created because of problems that arose due to the lack of precedence for racialized slave labor in European colonies. Most of these codes were written to regulate crime and punishments, but one very pivotal code created the basis for the institution of slavery in America for the next few hundred years.

That 1662 code stated “that all children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.” This legal definition created the rule that made the condition of slavery one that was acquired at birth. Over the course of human history, in many of the civilizations that practiced slavery, the condition of slavery was not genetic, nor acquired at birth. Slaves were typically prisoners of war or working off debt. At this point in colonial Virginia, English colonists created a new precedent for slave laborers that would be explicitly tied to Black slave laborers. Individuals were born into slavery, and it was rare to escape slavery.

The enslaved experience also varied depending on region, period, and owner; but typically, slaves’ lives were harsh with meager living provisions and physical punishments if a slave disobeyed orders. Slaves were considered the property of slave owners, property that could be bought, sold, punished, or even killed. Colonies each had different codes and laws to dictate slaves’ lives, but there were few, if any limits to regulate the physical abuse or even murder of slaves.

The narrative of the enslaved peoples has gotten very much distorted over the course of American history. Some students wonder why they were complacent to forced labor, and for much of this nation’s history, many people believed the Blacks were simply incapable of resisting. This is simply not true.

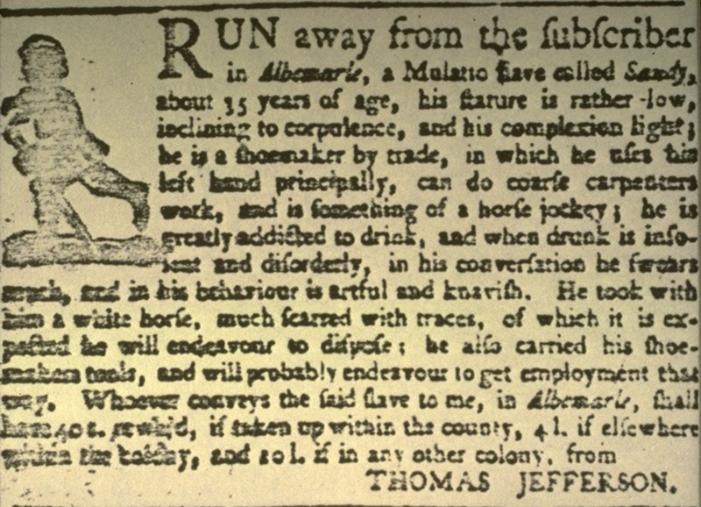

Slave resistance sometimes occurred even aboard the dreaded slave ships. Many slaves were shipped off to the Americas because they were prisoners of tribal war conflicts in Africa. Resistance on slave trade ships proved futile, but it still occurred. Upon arrival in the Americas, many different modes of resistance were common. Some were subtle, like working slow or feigning sickness. Others were more overt like running away from their captors. See the advertisement below meant to help the slave owner “find” their runaway slave.

1769 Virginia Gazette Advertisement

|

|

Ad placed in the Virginia Gazette in 1769. RUN away from the subscriber in Albemarle, a Mulatto slave called Sandy, about 35 years of age, his stature is rather low, inclining to corpulence, and his complexion light; he is a shoemaker by trade, in which he uses his left hand principally, can do coarse carpenters work, and is something of a horse jockey; he is greatly addicted to drink, and when drunk is insolent and disorderly, in his conversation he swears much, and in his behaviour is artful and knavish. He took with him a white horse, much scarred with traces, of which it is expected he will endeavour to dispose; he also carried his shoemakers tools, and will probably endeavour to get employment that way. Whoever conveys the said slave to me, in Albemarle, shall have 40 s. reward, if taken up within the county, 4 l. if elsewhere within the colony, and 10 l. if in any other colony, from THOMAS JEFFERSON |

Running away was the most common form of resistance to slave owners, and one that they vehemently tried to fight against, whether by physically punishing slaves or creating laws to sanction that violence. The other form of resistance that was much feared by slave owners was armed rebellion. While this was not very common, when it occurred, armed rebellion was met with harsh punishments and severe consequences.

The earliest organized rebellion to take place in North America was the Stono Rebellion. During this rebellion, slaves that had military experience were able to coordinate this rebellion through their training and shared language. They killed several White colonists in the process and conspired to make their way to Spanish controlled Florida, where there were Indians who harbored escaped slaves. One important detail is that as the slave rebels were briefly free, they moved about the town by shouting, “Liberty!” Up to this point, English authorities characterized enslaved Blacks as if they were incapable of understanding concepts of freedom and liberty like those that were so popular in the age of revolution. This incident in South Carolina proved contrary to their beliefs, reinforcing fears of slave rebellion on the scale of that that had just occurred in the nearby nation of Saint Domingue, now a free Black nation known as Haiti. From that point on, slave rebellion would be the most feared circumstances that slave owners could imagine, and they would do anything in their power to stop one from occurring.

As a reaction to this rebellion, harsher codes were established, ones that would prevent a future rebellion. New slave codes were introduced such as preventing slaves from leaving the property, congregating in groups, or even learning how to read and write. All of these were established, reinforced, and adopted in similar slave-based economies in southern colonies in order to control slave populations.

For most of the colonial period, contributions of those of African descent to the historical narrative was mostly tied to slave labor. There were few outliers to the story of hardships, racial violence, and victimization. However, men like Benjamin Banneker should be highlighted. He was born free and self-educated and managed to catch the attention of Thomas Jefferson in an exchange of letters. There is also the early case of Elizabeth Key, who was born of an interracial union and sued for her freedom and inheritance from her White kin. Hers was one outlying story of success where others were not as fortunate.

Also notable are the individuals who fought in the American Revolution. After the British openly recruited Black slaves to fight for the Crown to gain their freedom, General Washington was urged to open enlistment for Black soldiers in the Continental Army. This is one instance of early American history wherein Blacks and Whites fought in integrated regiments against a common enemy. America would not see this level of integration until the Vietnam War, nearly 200 years later. These are the real stories of Americans, who impacted American history small and big ways, notable against much adversity.

After the American revolution, as the early republic of America ratified the constitution and created its foundational laws, southern lawmakers saw fit to include provisions to ensure their interests would be protected. In doing so, these lawmakers also redefined the legal parameters of Blacks in America. As a compromise to include Black slave populations in the count to determine representation in Congress, the founding fathers included the Three-Fifths Clause in the Constitution. This law determined that for every five White men, three Black men would be counted in the state’s population. Southern lawmakers advocated for this clause to ensure maximum political representation on a federal level, while still diminishing Black slaves as property, not free citizens of the country. At this point in the nation’s history, citizenship was defined as your ability to vote, which was exclusively granted in most states to only White, property-owning men.

As North America continued to be organized into states, a delicate balance was established. Agriculturally based economies of the south allowed the practice of slavery in their states, which garnered the label “slave state.” In the north, where states later focused on industrial development, mostly outlawed slavery. These states were called “free states.” The U.S. government made the choice to keep a balance of both free and slave states as they continued to expand westward, to keep a balance of different political ideologies and economic interests were represented in government.

The African American experience from colonial times to the 1850s varied depending on region, time period, and of course slave or free status. Different factors over time, including ambiguity in colonial laws and manumission – the practice of voluntarily releasing one’s slaves from ownership, led to a significant number of free slaves in America by the mid-19th century. The majority of these former enslaved resided in northern states, but there were some in the south as well. Virtually all African Americans, whether enslaved or not, suffered racial discrimination. Years and years of Eurocentrism and White supremacy created an environment of racial oppression regardless of being “free.” Despite these hardships, being a free Black person in America was certainly preferable to being enslaved.

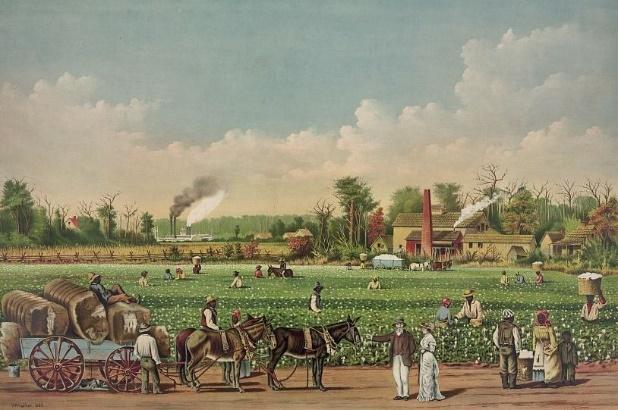

Despite the transatlantic slave trade being closed to the U.S. in 1808, slave populations continued to grow exponentially in the south. This was largely due to the precedent of the slave code of passing the condition of slavery through the matrilineal line. As Americans continue to expand into the west, slave population did as well, continuing to labor away on plantations across the south. Initially, colonial Americans held slaves in bondage as a necessity, a labor force that aided in building wealth and stability in the country. By the 1830s, use of Black slave labor was an integral part of the economy in the U.S. Between slave traders, auctioneers, investment bankers, and the planters themselves, most parts of the U.S. economy relied on the continued use of Black slave labor.

By the early 19th century there were a variety of ways slave owners justified continuing the practice. First, slave owners used the concept of paternalism to keep the practice. This concept argued that Black slaves were simply mentally incapable of taking care of their own well-being, therefore must remain in the care of their owners, who gave themselves the role of parent or guardian to a Black slave. George Fitzhugh, a pro-slavery advocate, claimed that “slaves are all well fed, well clad, have plenty of fuel, and are happy” (Fitzhugh, 1854). He asserted that without the efforts of slaver owners, “crime and pauperism” would increase; therefore, slave owners were also doing a service to the nation. Paternalism not only reinforced ideas of White superiority but masked the institution with the idea that slave owners were carrying out a noble service to the country.

Other justifications of continuing the use of Black slave labor included references to Biblical passages that referred to social hierarchy and obedience as well as references to ancient societies. For instance, because ancient peoples like the Romans practiced slavery, Americans remarked that they built that empire and their advancements in arts and sciences because they were not occupied with difficult labor that the slaves were doing for them.

Although there were many Americans that advocated for the continued use of slave labor, some decided that the enslaved should be set free. Abolitionists were people that believed that slavery should be legally abolished and rose out of an era of reform movements of the early 1800s. Abolitionists gained much support from the most pious individuals; many of which believed that the progression of America was inextricably tied to social reforms. Most abolitionists believed in ending the practice of slave labor altogether. However, there were some that believed in the concept of colonization. Colonization was the idea that Black slaves would be freed, but they could not remain in the U.S. In 1816, the American Colonization Society was formed to carry out this plan. A track of land called Liberia was purchased in Africa. This region would be the place that the freed slaves would be transferred to, instead of living free in America. This concept reflected the inherent racism that ran deep within American society, since even though they rejected the practice of forced labor, they still denied African Americans a place in society. Certainly, equality for Black men and women that were born in the country and participated and contributed to the nation was not an option for many Americans at this time. Although support for colonization was not widespread, there were still a few thousand Blacks that were freed and moved to Liberia under this plan.

Famous abolitionists during this period ranged from men and women, both White and Black. One of the most notable White abolitionists was William Lloyd Garrison, who published an abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, which communicated the ideals of emancipation and freedom to the public. Similarly, a woman named Harriet Beecher Stowe published a book called Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a narrative based loosely on a slave’s life. Both individuals used their voices to carry a message to the American public about the moral wrongs of slavery and its continued use in the U.S.

Even more significant were the Black abolitionists voices of the time. Fredrick Douglass was perhaps one of the most notable of the time, for he was a self-educated runaway slave. A skilled orator, Douglass spoke passionately about many issues plaguing the U.S. of the time, chief of which was slavery. Most Americans would also recognize the name Harriet Tubman, for she was known not only as a runaway slave, but a woman who helped many others runaway from enslavement and hide in the North. To her own risk, Tubman made several trips back and forth over the Underground Railroad, a nickname for a series of trails and safehouses that led slaves to safety in the North. While Tubman successfully traveled from Maryland into Pennsylvania, the Underground Railroad network had routes into other areas in the North and also Canada and even Mexico.

By the 1850s, the political debate regarding the institution of slavery had affected lawmakers in significant ways. First, after the Mexican American War, the U.S. acquired a wide swath of land – land that would eventually be organized into states. The potential for additional states in the Union meant the disruption of the delicate balance of free and slave states. The debates that raged amongst lawmakers was how to determine the status of these states. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 stated that any territory above the 36 30 parallel could not be designated slave states. However, some politicians argued that new territories petitioning for annexation as a state should utilize popular sovereignty for determining status. Popular sovereignty meant that the residents of a state should vote on whether the state enters the Union as ‘free’ or ‘slave.’ Again, this meant the potential disruption of balance between free and slave states, also tipping the balance of power in Congress.

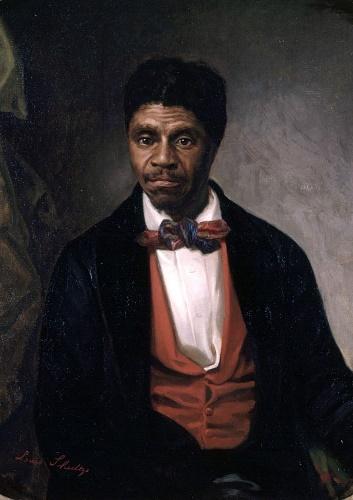

Additionally, a pivotal case was tried in the courts in 1857. Dred Scott v. Sanford regarded a slave who was petitioning for his freedom. Dred Scott was a slave that was relocated with his owner to the state of Illinois, a free state. Scott believed that since he was living for several years in a free state that must mean he was no longer a slave. However, the U.S. Supreme court ruled against Scott. In his statement after the ruling, Chief Justice Taney declared that Scott was not a U.S. citizen; he was property, “not entitled as such to sue in its courts,” and that his lawsuit was invalid. Additionally, Chief Justice Taney made statements regarding the inferiority of Black slaves, and that the “negro…be reduced to slavery for his benefit....” The decision of the court determined the legality of ‘free’ and ‘slave’ state distinctions. Effectively, Taney’s statement made it unconstitutional to ban slavery in any state, inflaming the slavery debate across the country, and deepening the sectional divide of the time (Taney, 1857).

To further deepen divisions in the U.S., a presidential election was at hand in 1860. South Carolina leaders went public with statements threatening to secede from the Union if candidate Abraham Lincoln was to become president. Southern political leaders feared that if the Republican party lead by Lincoln was to gain more power, the party would threaten states’ rights to uphold the institution of slavery. Once Lincoln was elected, southern states one by one voted to secede from the Union. Only after civil war would the country become whole once again.

The American Civil War continued to stretch the limitations of race relations in America. As the Confederacy pitted itself against the Union, thousands of Americans were killed. Initially, African Americans from all over the nation were eager to join the fight. White Union soldiers joined the fight for many reasons - abolition, draft, patriotic duty and more. For Blacks, joining in the war effort meant that they were fighting for their freedom. However, for the initial years of the war, Blacks were prevented from enlistment. Only after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued were Blacks allowed to fight. Even when enlisted, these men were segregated from White soldiers, trained and led by White men, and paid less than their White counterparts at the same ranks. Contrary to popular belief, the proclamation did not free all the slaves. The Emancipation Proclamation freed the enslaved who resided in states that had seceded from the Union. There were still some slave states where slavery remained untouched. Slavery would not be officially abolished in America until the passage of the 13th amendment in 1865.

As President Lincoln promised, a “new birth of freedom” (Lincoln, 1863) was made possible after the dust settled from the Civil War. The Reconstruction era promised much hope for newly emancipated slaves. Although slavery was officially abolished in January of 1865 and war ended in April of the same year, Juneteenth – June 19, 1865, is traditionally the day that was declared Freedom Day for African Americans in the U.S. For the formally enslaved, freedom did not just mean the end of slavery, but it meant the opportunities that most did not have access to before 1865. First and foremost, Black communities wanted access to land and voting rights. Since the revolution, these have been the hallmarks of American freedom. Other freedoms came with being newly freed in the U.S. like being reunited with lost loved ones after being sold away, access to education and medical care, the ability to buy a weapon, and for some, even running for political office.

Only these freedoms were not guaranteed in the era of Reconstruction. Although the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments protected the rights of most African Americans, this legislation was not easily accepted by southerners who sought to maintain White supremacy. Very quickly, vigilante groups were formed to prevent Blacks from Constitutional freedoms, especially those that attempted to run for office, buy land, and even cast their votes. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan formed to enact violence and intimidation in communities that attempted to exercise their rights. Eventually, Congress issued measures to allow military occupation of former confederate states to protect Black communities. Additionally, legislation was enacted to root out and suppress KKK and other vigilante groups from operating.

Eventually, political pressures led to a compromise that ended military occupation in the south as well as drawing back on pressures to maintain peace. During the election of 1876, Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes’s victory was at question due to a very narrow margin of victory. In order to secure enough support to maintain a Republican in the White House, political leaders made a compromise to secure Hayes’s victory but vowed to withdraw federal troops from southern territories. Effectively, Northerners waning interest in supporting measures of racial equality in the U.S., coupled with a danger of political power, equaled the end of Reconstruction.

1877 TO WWII

After the failures of Reconstruction, the southern leaders reasserted their White supremacy in politics and society. As the south began to industrialize, agriculture remained at the center of most state economies. Tenant farming or sharecropping was one of the ways to suppress the economic progress of southern Blacks. Banks, politicians, and others worked together to prevent Blacks from purchasing land for farming, whether it be with aggressive intimidation or simple denial of bank loans (Coates, 2017). Relegating Blacks to sharecropping kept them under the control of White landowners, while also preventing economic growth.

Other forms of oppression included voter suppression. Measures were adopted in many counties across the south to prevent African Americans from registering to vote. These measures included poll taxes and literacy tests. Most of these measures were directed solely to African American communities.

Post-Reconstruction, the so-called New South also adopted a concept called the Lost Cause. This concept rewrote the events of the Civil War for southerners, elevating and romanticizing the war to make former Confederate soldiers’ heroes to their cause – defenders of the south and states’ rights. Monuments were built to glorify southern military leaders, Confederate flags were flown on state buildings, all meant as a reminder of the glorified Confederate past. Many regarded these actions as a reinforcement of White supremacist power in the south (Kytle & Roberts, 2018). This was a reinforcement of racial hierarchy and each symbol of the Confederacy signaled fear and intimidation in the hearts and minds of African Americans for several more generations.

Additionally, in 1890, a monumental case was tried in the supreme court that would impact the south for the next few decades. This case regarded a man who was descended from both White and Black ancestry named Homer Plessy. Plessy was arrested for sitting in a rail car designated for only Whites according to the Louisiana Separate Car Act. After the case was tried in the U.S. Supreme Court, the justices ruled that the segregation law was constitutional, and from then on, the “separate but equal” clause established racial segregation laws in many southern states. This clause meant that if separate facilities for Whites and Blacks were deemed “equal,” but only designated for use by skin color, racial segregation was Constitutional. Plessy v. Ferguson became the basis for racial segregation in state institution and public places like schools, restaurants, water fountains, and more.

The Plessy verdict marked the beginning of an era known as the Jim Crow South, an era that would not end until the 1960s. Any state that adopted racial segregation laws after the Plessy verdict was considered a Jim Crow state. Jim Crow refers to a character portrayal of a Black slave from the mid-19th century. This caricature was often found in minstrel shows, racist shows that contained skits and mini plays that portrayed the Black slave as unintelligent, subservient, lazy, and almost clown like. Usually, White performers would wear blackface – painting their faces black to play these roles. These types of shows continued in popularity well into the 20th century.

Along with Jim Crow laws arose an unspoken code of racial norms that were adopted in much of the south. These racial norms stemmed from the slave to master relationship of the distant past. These societal rules dictated that African Americans should always show deference to Whites in society, regardless of age, sex, or any other differential factors. Examples of this deference would be offering a White person a seat on public transportation, moving aside to let a White person pass, or even avoiding eye contact with a White person.

Another element of White supremacy and reinforcement of power in the Jim Crow South was racialized violence in the form of lynching. Lynching was the act of carrying out extralegal punishments on individuals without fair trial. These violent, racial attacks were mostly doled out to Black men under the suspicion of violating social norms. Many of these public executions were provoked by the supposed attack or offense to a White woman. The range of violence in lynching was wide, some public hangings, others included harsh corporal punishments and torture, often committed by multiple individuals. Some lynching acts were carried out as spectacles, wherein the victim of the punishments was held until a crowd could build up in number to watch. This vigilante justice maintained the structure of White power especially in the deep south for much of the early 20th century.

Despite all the elements of subjugation that the African American communities throughout the nation endured, many notable figures prevailed in uplifting and advocating for Black civil rights. For instance, Booker T. Washington was born from slavery but still advocated for Black rights. Washington believed that African Americans should support each other in building businesses and wealth within their own communities. This would be accomplished by becoming educated, especially in a trade skill. Washington sought to work within White systems and institutions to accomplish his goals.

W.E.B. DuBois was another man who pushed the envelope further. DuBois believed in pushing against the status quo by challenging racial inequalities in America. It was DuBois that helped established the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Because of the increased racial violence and discrimination in the Jim Crow South, many African Americans fled from the deep south for larger more metropolitan cities like New York City, Detroit, and Chicago. Beginning in about 1916, this movement of African Americans was called the Great Migration. Moving out of the rural deep south not only meant distance from racial segregation laws but more job opportunities.

In New York during the 1920s, African Americans thrived during a period dubbed the Harlem Renaissance. The arts, in different forms, music, literature, poetry, and more were cultivated and explored by Black artists during this time period of explosive creativity. Jazz music as well as blue is attributed to Black communities. Notable authors like Langston Hughes and Alain Locke inspired one another as well as other writers in the community.

And although the 1920s was a thriving post-war period of culture and wealth, Black communities were never far from racial violence and oppression. In 1921, Tulsa, Oklahoma saw one of the most violent attacks motivated by race in the country. The Black community of Greenwood was a thriving, economically successful community. This area was known as the “Black Wall Street” due to its economic success. The Tulsa Massacre of 1921 was inspired by an alleged attack upon a White woman named Sarah Page by Dick Rowland. Rowland was taken into custody and a lynching was said to have been planned. Members of the Black community attempted to stop this lynching, and a violent altercation erupted into a riot. This riot devolved into a full-fledged massacre and destruction of Greenwood. Bands of White attackers descended into Greenwood to attack and kill Black men of the community, as well as loot and burn businesses. This attack only ended when state authorities instituted martial law. The details of this attack had been obscured over the years, mostly downplayed by White authorities. There was little to no justice served for any of the crimes committed. The number of deaths is still unknown and property damage was extensive.

Wartime, for African Americans, provided opportunities for people of color who would not normally have opportunities. Depending on the period of history, war provided Blacks the opportunity to express patriotism, earn a fair wage, or participate as an American, even when they were not granted the rights and privileges of other Americans. African Americans fought in every armed conflict in this nation’s history, beginning with the American Revolution. By WWI, Blacks continued to serve in the military, despite being paid less, being segregated from Whites, and disrespected as returning veterans.

World War II signaled a different opportunity for African Americans. As the working class was drafted into war, factories were left to hire amongst the pool of Americans that were left. This meant employment opportunities for those who did not have prior access to well-paying industrial jobs – people like women and African Americans. However, racial discrimination still provoked companies from allowing Blacks access to these jobs. Only after A. Phillip Randolph threatened a large-scale protest in Washington D.C. did President Roosevelt issue Executive order 8802. This order prohibited employers from racial discrimination when hiring employees in defense industry jobs. Although this was a wartime provision, this order opened the door for African Americans to continue their push for racial equality in the near future.

Gainful employment and better wages during and just after the war only meant incremental changes for African Americans. To uphold the status quo of White superiority, the practice of redlining became common in the U.S. Redlining is the discriminatory practice of denial of services, usually bank loans, to individuals that lived in areas deemed “hazardous” or poor. These redlined areas were usually populated with people of color. In practice, this was the prevention of allowing African Americans and other racial minorities from leaving these redlined areas, despite their financial status. This denial of opportunity was often extended to other areas such as better education and health care.

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT OF THE 60S & 70S

The Cold War era is the period that further inspired African Americans to mobilize against issues of racial segregation and demand racial equality. The end of WWII left the U.S. promising to promote self-determination of politically weak nations and the protections of humanitarian rights throughout the world. But if Americans could uphold these commitments for foreigners, what about the inequities at home? African Americans and other racially minoritized groups were asking these questions, which led to the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

There were many hallmarks of the African American civil rights movement, and here are just a few significant events. The first hurdle to cross for the movement was to undo the years of segregation laws that prevented African Americans from exercising their fundamental rights as citizens of this country. The monumental court case to overturn racial segregation began with children attending schools, specifically Oliver Brown and his daughter Linda. She had to walk six blocks to catch a bus to attend an all-Black school; however, a White school was located much closer to their residence. Brown and other parents formed a class action lawsuit against the Board of Education to challenge segregation in schools. This case made it to the U.S. Supreme court, and the result was monumental. Brown v. Board of Education both gave momentum to the civil rights movement and took a great step forward in the fight for racial equality. In a single opinion statement given by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the court overturned the “separate but equal” clause of 1890, ending racial segregation in schools. Read the monumental decision below.

Other strides were made to challenge segregation laws in Jim Crow states. To challenge segregation in public transportation, individuals like the infamous Rosa Parks, Claudette Colvin, and Sarah Keyes either refused to give up their seats, or remained sitting in ‘White’ sections of the bus until they were arrested. The consequential Montgomery Bus Boycott left buses in Alabama vacant for months, until racial segregation on buses was declared a violation of civil rights under the law. Later, the Freedom Riders, both Black and White members of the Congress of Racial Equity, or CORE, continued this work by checking the compliance of desegregation on buses. The activists that defied long held racial norms were met with strong opposition, often turning brutally violent. Eventually, the Interstate Commerce Commission complied with desegregation laws.

Beginning in 1960, more young organizers staged sit-in protests in restaurants and diners. Again, the sit-ins were meant to challenge segregation laws in these businesses that separated White and Black customers. Sit-in protesters would sit in ‘Whites only’ sections, attempting to be served. Again, the sit-in activists were subject to taunts, food thrown at them, and even beatings by Whites who wanted to maintain the dominant power structure. These protests began in North Carolina and later spread to other major cities.

Regarding racial protests and organizing, there were no other famous figures of the Black civil rights movements other than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. King was key to grassroots organizing in this era, forming the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or the SCLC. King and his supporters committed to non-violent protests – civil disobedience. The strategy was to create social change by disrupting civil order but also rejecting violent acts of opposition. King staged many marches and protests using this strategy, including the famous March on Washington D.C. in August of 1963. The “I have a dream” speech has been made famous since, but in the moment, inspired many to support racial equality.

Eventually, all this organizing and demonstrating would result in legislative change. Under President Johnson, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. This act outlawed all discrimination in public facilities based on color, religion, sex, and national origin. Later, after further demonstrations that unraveled into violence, the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, outlawing the denial of suffrage to African Americans through literacy tests, poll taxes, or any other means of disenfranchisement. Voting rights, a touchstone of American democracy and freedom, was finally within the reach of Black voters, with legislative measures to protect their rights as American citizens.

Despite these various strides forward in the civil rights movement, at every step participants were met with aggressive and oftentimes violent opposition. The Freedom Rider buses were attacked and firebombed. Marchers in Alabama were met with attack dogs, fire hoses, and arrests despite their commitment to non-violence and the presence of children. In a devasting bombing of the historic Black church, the 16th Street Baptist Church was attacked, resulting in numerous injuries and the tragic deaths of four young girls. During the efforts to integrate schools, children were met with organized opposition in the Massive Resistance movement. Southern White politicians, school boards, and White parents worked together to stop desegregation. In some cases, they even closed schools down to prevent schools from becoming integrated.

By the end of the decade, the movement became somewhat fragmented. With the assassination of Dr. King in 1968, and numerous other protests and domestic turmoil throughout the nation, the movement lost some focus. In the case of the Watts Riots of 1965, a traffic stop of a Black man devolved into days long riots in the Los Angeles area resulting in numerous deaths and millions in property damage. The end of the decade found conservative lawmakers characterizing the civil rights movement as part of a nationwide issue of unrest and the rise of criminal behavior. The push for law and order, as well as the rise of the conservative right brought the civil rights era to a definitive close with the election of Reagan in 1980.

THE RECENT PAST

In the final decades of the 20th century, African Americans continued to push against racial oppression. They continued to face issues like wage inequality, racial profiling, general racial discrimination and more. Measures like affirmative action attempted to address racial inequities but were debated and rejected.

Jesse Jackson was heralded as a symbol for change as he embarked on a Democratic Presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988. Numerous other Black politicians entered public service offices. Of course, the most recent and notable Black politicians in American history is Barack Obama, who was voted president in 2008 and served until 2017.

Popular entertainment would also see the successes of comedians like Eddie Murphy and Whoopie Goldberg, actors like Denzel Washington and Viola Davis, musicians like Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston, and of course, Oprah as an arbiter of culture.

Despite these successes, the underbelly of race relations in the U.S. is exemplified in the various deaths of many Black men and some women, mostly at the hands of the police or White citizens. Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Philando Castile – as well as most recently Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd are just some of the names of controversial deaths in recent years. The Floyd murder at the hands of the police spurred another surge in the social movement Black Lives Matter, a movement that advocates against police brutality and racially motivated violence. In 2020, protests erupted nationwide objecting to systemic racism that permeates American society. Supporters of the movement seek to undo racial inequities in education, employment, and other walks of American life.

Although the debates for racial justice, solutions for racial inequities are still ongoing, there is much to learn and reevaluate about African American historical narratives. African American history is American history as much as any other racial and ethnic group in this country and should be recognized for the role and place they have in the nation’s history.

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 4.1

A PROUD AMERICAN OR A PROUD AFRICAN AMERICAN?

That is a question for the ages. We all have an identity. The question is, is the identity framed from within, or is it assigned to us? I think about that a lot, and I believe I have come to an answer of sorts, even if not all will agree with me. As a man of color in America, I am also an American who incidentally happens to be a man of color. What’s the difference you say? Well, read on friend, then you can tell me.

I grew up in a mixed neighborhood, where all the primary races were present within a three-block radius, any direction you looked. And I attended a parochial school where less than one percent of the student body was of color. Each day I stood and proudly said the Pledge of Allegiance. I didn’t notice that my being African-American meant anything more than the student next to me being a Caucasian-American. Race was not discussed openly. In a very real sense, I was color-blind.

I was quite proud of my father who was in the Army, a veteran of both the Korean and Vietnam Wars. My mother worked as a civilian contractor for the military, at one point elevating to Regional Director for the Contracting Division in Fort Lewis, Washington. I have every reason to be proud of my parents. They served the American military community very well. They served America well.

And I myself am a veteran, having served four tours as an Air Force Officer and language development instructor for military dependents.

I am happy, and to be plaintive—very proud to have served the United States of America. I stand on the shoulders of men and women of color who served, died, and survived wars spanning the past 80 years. They were often mistreated by their peers and supervisors even as they served because they were people of color. They were overlooked for military honors, they were placed on the front lines of danger in disproportionate numbers, as they were considered “expendable.” Others worked hard to qualify for high-profile military positions and after qualifying, were designated as cooks or custodians. These actions were prevalent, unfair, and a shameful stain on the proud record of service that all veterans share.

But it cannot be doubted that these minorities did serve America, regardless of how they were treated. I, for one, consider them proud Americans, period. Many will say to me, “What’s wrong with being a proud African-American?” My answer: not a thing.

But at the end of the day, I know I still salute the American flag that I served. Oh yes, I am proud to be an African-American, but that is actually saying that there is nothing at all wrong with being an African-American. My racial pride hinges on the fact that others need to be reminded that I have nothing to be ashamed of for being Black. Being Black is not a noteworthy accomplishment, it is quite simply what I was born to be. I thank the many that have fought to preserve my racial dignity, and I will never forget what they did to pave the way for my success in life.

But what I have personally accomplished in life as a military veteran, college professor, etc. is a result of living in a country that allowed me to be those things.

So, for me, I am more than content to be known as an American whom God created with African ethnicity, living in this great country called America.

What does the author mean by “American” as opposed to “African American?” Do you agree with the author’s point of view? Why or why not? Do you think the issue the author discussed is as important today as it was 20 years ago?

This story “Proud American Or A Proud African American?” by Daryl Johnson is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

SUMMARY

African Americans are an integral part of U.S. history, despite being enslaved, discriminated, abused, and disregarded for so long. They came to this country by use of force, and with their agricultural labor, built up American wealth and institutions. Despite the constraints of chains and physical abuse, they fought for their freedom and helped rebirth the nation with new ideas of liberty and democracy. However, again being suppressed and segregated in the 20th century, Black communities arose again to lead civil rights movements of the 1960s to redefine freedom once again. Now in the modern era, the fight for equity continues as racial minoritized groups continuously call out and dismantle systems of oppression, pushing for American progress.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- How did the trans-Atlantic slave system contribute to the development of colonial America?

- How and why did Virginia shift from indentured servitude to slavery?

- What reasons did 19th century slave owners use to justify the use of Black slave labor?

- Why did Reconstruction end, and what effect did it have on free Black communities?

- What are Jim Crow laws? Why were they adopted in many southern states?

- Explain key events and figures of the civil rights movement. How did the movement develop?

TO MY FUTURE SELF

From the module, what information and new knowledge did I find interesting or useful? How do I plan to use this information and new knowledge in my personal and professional development and improvement?

REFERENCES

Blight, D. W. (2001). Race and reunion: The civil war in American memory. Harvard University Press.

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 1. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 2. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Kytle, E. J. & Roberts, B. (2018). Denmark vesey’s garden: Slavery and memory in the cradle of the confederacy. The New Press.

Locke, Joseph & Wright, B. (2019). The American yawp. Stanford University Press. http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html.

Ortiz, P. 2018. An African American and Latinx history of the United States. Beacon Press.

Rothenberg, P. S. (2016). Race, class, and gender in the United States: An integrated study. (10th ed). Macmillan.

Takaki, R. (1993). A different mirror: A history of multicultural America. Back Bay Books.