3: Our Story - Native Americans

- Page ID

- 145365

At the end of the module, students will be able to:

- summarize the development of indigenous peoples across the Americas during pre-colonial times

- explain the process of European contact and colonization in North America

- explore the process of American westward expansion

- understand the political and legal processes that Americans utilized to control and subjugate Native Americans

- describe aspects of the American Indian Movement of the 1960s

- explore the issues of the late 20th and early 21st century and how they have impacted Native Americans

KEY TERMS & CONCEPTS

|

American Indian Movement American Indian Religious Freedom Act Americanization Bering Strait Blood Quantum Cahokia California v. Cabaz Christopher Columbus Dakota (Sioux) Uprising of 1862 Dawes Act of 1887 Doctrine of Discovery Eurocentrism Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 Indian Education Act of 1972 Indian Relocation Act Indian Removal Act of 1830 |

Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 King Phillip’s War Long Walk Manifest Destiny Meriam Report Occupation of Alcatraz Proclamation Line of 1763 Pan-Indian Pequot Massacre Reconquista Red Power movement Sand Creek Massacre Seven Years’ War Trail of Tears Worcester v. Georgia |

INTRODUCTION

Native Americans are unique to the American story, for they were indigenous to these lands before they were even named the Americas. Once the “New World” was discovered, indigenous peoples had to grapple with foreigners colonizing their land. The Native Americans functioned in two different modes over the course of American history: by resistance to power and attempts to work within the framework of the U.S. government.

This is their story.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF THE AMERICAS

The peoples of the Americas arrived approximately 12,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic Age. A “small” ice age left the Bering Strait frosted over, which allowed for people to cross from the continent of Asia into modern day Alaska. Over many decades, small groups of nomadic peoples traveled long distances and spread throughout the Americas, some migrating all the way to South America.

As the decades passed, the nomadic peoples settled all throughout the lands, and began farming and sedentary living approximately 8,000 - 9,000 years ago. From there, they developed into vastly different tribal groups, some creating massive civilizations that were fairly advanced for their times. These civilizations include that of Cahokia rooted along the Mississippi river, who in the height of their power had a population of up to 30,000 and trade networks that reached modern day Mexico.

For many decades, up until the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans lived in North America in relative peace and harmony. Each tribe developed a unique society based on their surrounding terrain and climate as well as familial alliances. Conflict between tribes was typically based on border disputes, but rarely large-scale political warfare.

CONTACT AND CONFLICT WITH THE “OLD WORLD”

For centuries, Native Americans lived, cultivated, and developed the lands in the Americas. The lands would not see significant changes until European contact in the late 15th century. Most readers would attribute the first European to come in contact with indigenous peoples to be renowned explorer Christopher Columbus. This is generally true, even though Norse explorer Leif Eriksson landed in Newfoundland in the 12th century.

Columbus was one of many skilled explorers of the 15th century dared to venture out into open ocean, first making their way down the African coast, then planning to sail out further into the Atlantic. Columbus, although an Italian in origin, gained a commission from the Spanish monarchy to explore and colonize new lands. The Spanish were highly motivated by the Reconquista, the campaign to “reconquer” Spain from the Muslims that had occupied their native lands for decades. In 1492, they accomplished their Reconquista and were eager for more victories. Due to Ottoman expansion, historic routes to the east were no longer viable, and Europeans were looking for another access point to eastern spices and other exotic goods. Columbus was hired by the Spanish monarchs to find a new trade route to Asia in order to access highly coveted commodities.

When the Spanish made landfall in the Americas, not Asia as they planned, they sought to explore the Americas, searching for gold and other lucrative natural resources. Upon discovery, the indigenous peoples were dubbed “Indians,” for Columbus and his shipmates believed that they landed in the East Indies. The Spanish utilized the papal principle of the Doctrine of Discovery which sanctioned the colonization of the Americas and declared indigenous peoples’ non-Christian enemies that deserved the brutal conquest of their lands.

In Columbus’s journal, he recorded his observations of the indigenous people. He stated:

It appeared to me to be a race of people very poor in everything…

They should be good servants and intelligent, for I observed that they quickly took in what was said to them, and I believe that they would easily be made Christians, as it appeared to me that they had no religion.... (Columbus, 1492)

Columbus shows an obvious superiority to the people he encountered by calling them poor, assuming they were without religion since they were not Christian, and declaring them to be of service to others like him. He shows intent to abuse and enslave, and this is the sentiment that many other Europeans would take as they began to colonize the Americas. From here on forward, Europeans set a precedence of Eurocentrism, the interpretation of non-European world civilizations in comparison to European culture. In these cases, European men like Columbus viewed the indigenous peoples as different and inferior, thus justifying abusive and malicious behavior. Spanish Conquistadors continued to explore in the Caribbean, Central, and South America, trading, warring, and colonizing regions. It was the Spanish who set the precedent to establish colonies in the New World for the sole purpose of monetary benefit to its mother country. Eventually they established very lucrative settlements with systems that forced indigenous peoples and imported African slaves to work against their will. Soon other Europeans ventured into the New World with the hopes of establishing their own profitable settlements.

ENGLISH COLONIAL PERIOD

English explorers intended to take the same routes into the west as the Spanish but were most successful in the settlement of North America. Two primary colonies were established in what is now the American east coast – the colonies of New England, now mainly Massachusetts, and Virginia. In each of these regions, English settlers also encountered indigenous peoples; however, the English approach was initially different than the Spanish. The English sought to forge alliances with Natives, learn the territory, and convert the Natives to Christianity. Eventually, the desire for expanding territories, along with the general beliefs of White superiority, would break down attempts of coexisting.

However, we must not assume that indigenous peoples had no agency or free will. As the English began to populate North America to form colonies that would become America itself, they encountered Natives that saw opportunities for trade with the light skinned newcomers (Lepore, 1998). Evidence shows that the weapons Europeans welded were coveted by some tribes to give them power over tribal disputes. Native Americans also traded with the English for glass beads that they considered valuable, but the English viewed as meaningless. These trinkets circulated amongst the tribes as currency.

As the English flooded into the eastern seaboard of North America, they quickly became the dominant colonial power. Settlement was difficult and intermittent conflict with Native Americans kept the English close to their fortified settlements. At times, Native Americans worked with colonists as exemplified in the story of Squanto, who was said to have been present during the first Thanksgiving feast. Squanto was a man who had already had some exposure to the English and could communicate with the colonists. This brief period of harmony would be short lived in the New World.

When the English came and settled, the fundamental changes to the land and its people were significant. First, the impact of disease has to be considered. Native Americans had no immunities to diseases that the Europeans brought with them, and their communities were tragically impacted. These diseases included smallpox, influenza, and plagues that decimated Native populations. Next, there was a culture clash that caused many problems. The English brought herding animals like cattle and sheep that were not native to the Americas and needed land to graze. These wandering animals often disrupted Native life and the forest ecosystems. Trees were also felled to create space for planting crops, sustenance for the influx of colonists in the lands. Over time, the settlers would need more and more land to spread out, and territorial lines would be both fought over and ignored. In certain areas, finite resources and trade disputes occurred, resulting in a need for revenge and retaliation.

One of the more significant was the Pequot Massacre, which occurred in May of 1637. Exhibiting the land lust of the colonists, a militia of soldiers from New England stormed into the region they referred to as Mystic and attacked the Pequots. The village was set on fire, and any Pequots attempting to escape were shot. Survivors were sold into slavery, and the whole affair was justified by the will of God, as the colonists were Christians. This was viewed as a triumph for the English, and more land was used to settle upon.

Tensions continued to mount in the New England region until all-out war broke out. The body of an Englishman named John Sassamon was found and suspicion turned quickly to the Wampanoags, the prominent tribe in the area. The Native American’s men suspected of the murder were put to trial, found guilty of the crime, and executed. The Wampanoags retaliated and killed nine English colonists. This violence would escalate into a violent and bloody conflict called King Phillip’s War. The Native American leader Metacom, known to the English as King Philip, led a coalition of Natives in the attack of several Puritan townships. Metacom had previously maintained a modicum of peace, and even small conflicts were negotiated by both parties. The execution of the three Natives proved a step too far and showed that the colonists were overstepping their boundaries. The colonists, however, viewed the Native Americans as godless savages and an impediment to English success and growth in the new world. It was widely believed that natives were inferior to Europeans and were not using the land to its full potential. With these ideas in mind, war was easy and simple. War waged for months as the English attempted to chase Metacom and their supporters in lands they did not know well. Finally, the sachem Metacom was captured and put to death. The war was over, and the English remained dominant.

One weakness in the eyes of the English was the fact that the Native Americans seemed fractured and easily manipulated. This was due to the numerous tribes that existed in North America, each with varied culture, loyalty, and territory. Although the natives might have appeared the same to the English, they were not united. These tribal differences were often exploited by the colonists, and their loyalties were traded and bought by the different groups in colonial times. This is best exemplified during the French and Indian War, sometimes also called the Seven Years’ War. In the colonies, this conflict was fought between the French and the English, each with their own Native American allies. One of the boons of this war was the area known as the “middle ground” or the Ohio River Valley territory. Again, we can observe another instance of colonists wanting to spread and continue to settle westward. The end of the war resulted in victory for the English; however, Parliament also passed the Proclamation Line of 1763, an act that prevented the colonists from settling past the territorial line along the Appalachian Mountains and the far eastern boarders of the English colonies. Essentially, the English colonists did not gain control of the Ohio Valley as they hoped. Despite the boundary set by Parliament, many colonists ignored the law. Violations were common, and even General George Washington himself crossed this territorial divide.

Throughout the colonial period into the formation of the United States, Native Americans saw their lands taken over by English settlers. Once the revolution ended and the Americans achieved freedom from the British, the Americans looked to the west to expand their territories. Some attempts of pan-Indian alliances were forged to fight against the American aggressors. The term Pan-Indian refers to a coalition of Natives from different tribes working in unity against a common enemy. These attempts were led by Native Americans such as Tecumseh during the War of 1812, who sought to use force to defend and take back their lands. Tecumseh asserted that their land once “belonged to red men” and had “since made miserable by the White people” (Tecumseh, 1810). Although Native Americans were treated as sovereign nations when signing treaties, the respect for Natives was often ignored when they were regarded as inferior and unable to maintain control of their lands. The American government repeatedly reneged on treaties, and new states formed as populations expanded. When U.S. citizenship was established, Native Americans were not extended the rights of other White Americans, not for more than 100 years later.

WESTWARD EXPANSION

Most of the 19th century was a time of great turmoil and despair for Native Americans. The U.S. government approached relations with Natives in two different ways, first removal and relocation; then land redistribution and assimilation.

Between the 1820s up through the 1880s, Native Americans were continually uprooted and relocated to reservation lands. These actions were legitimized by the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, under President Andrew Jackson. This act passed with President Jackson’s approval and was later carried out under his predecessor Martin Van Buren. President Jackson claimed that Native Americans were “uncontrolled possessors” of their lands, and therefore would only be allowed to occupy lands that were given to them by their conquerors (Jackson, 1829; Richter, 2001). The act allowed for the removal of five different tribes from their ancestral lands to relocate to reservation territory in modern day Oklahoma. The former lands would later be settled by White Americans.

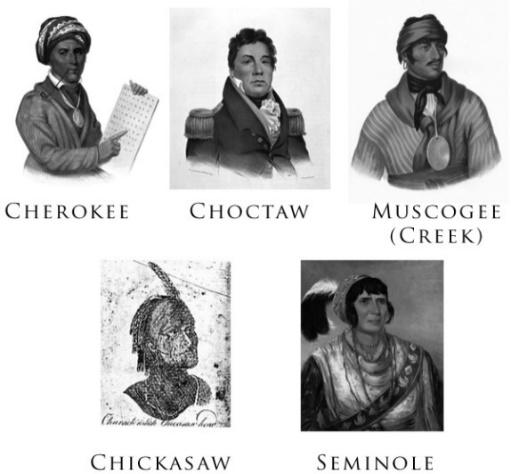

In a shift of tactics, instead of using force to combat the removal process, one of the five tribes, the Cherokee, sought to work within the U.S. legal system to sue for their rights to their land. This was an uphill battle, especially after Georgians discovered gold in Cherokee territory in 1829, making their territory highly coveted. After tumultuous court battles, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court upheld Cherokee rights to their lands. Unfortunately, even this court ruling was not enough to protect the tribes, and over the course of several years, the five tribes: Chicksaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Creek, and the Cherokee were forced from their homelands to a territory west of the Mississippi River. The removal process took several years and was later named the Trail of Tears. The reason for the name was because the relocated Natives took the forced journey on foot, many of them dying of exposure, disease, and starvation. Men, women, children, the elderly, the infirm – they were all forced to walk with their possessions, no wagons, no horses, tents, or provisions. One in three died on the journey, and they barely made it to their destination.

The interactions between the Americans and Native Americans during the 19th century were justified by a concept that was coined into words by John O’Sullivan in the 1840s – Manifest Destiny. O’Sullivan successfully illustrated a concept that was already ingrained in the minds Americans since the initial settlement of this country. Manifest destiny was the belief that Americans had a destiny, a calling that could not be changed. That destiny was to inhabit the lands of North America from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast. Additionally, O’Sullivan was clear that this “destiny” was dictated by God, underpinning this concept with the most prevalent religion in America of the time, Protestant Christianity. By giving this concept a name, O’Sullivan gave Americans a justification to continue to settle and occupy all the lands in North America, continually pushing westward no matter what was in their way because it was their destiny. What he really conceptualized were the beliefs and desires of even the earliest colonists, who had journeyed west across the Atlantic Ocean so long before him. In this era, Manifest Destiny was not merely about colonial settlement, but American domination of land, resources, and societal order.

This maltreatment continued amidst the American civil war. Even as the country was torn by armed conflict, American citizens kept a steady pace on their quest for westward expansion. In what is Minnesota today, the Dakota tribes fought for their rights to remain in control of their lands in a conflict called the Dakota (Sioux) Uprising of 1862. Because of the severe depletion of buffalo herds, which was the tribe’s main food source, the Dakota tribes resorted to farming, which was not working out well. The tribes were then forced to resort to asking the state government for aid, or buying food on credit, or else their people would starve. Local authorities refused to comply and tensions rose. A group of Dakota men killed five White settlers, and violence continued to escalate into war with the Dakotas. By the time local militias ended the violence, hundreds of Dakotas were taken prisoners and held accountable in courts of local authorities where murder, rape, and atrocities took place. Officially, 303 Dakota tribal members were sentenced to be hanged, until President Lincoln stepped in and commuted most of the sentences to 38 individuals. This was the largest mass execution by hanging in U.S. history. The remaining members of the local Dakota tribes were chased into the hills, hunted, killed, and starved out.

After the events of the Dakota Uprising, more and more violent incursions occurred. In 1864, the Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes attempted to protect their lands in Colorado. However, when gold was discovered on their lands, Americans sought to gain access. The tribes sought peace negotiations, but Colorado militiamen forged a different path. In a violent attack called the Sand Creek Massacre, a White militia openly attacked the tribes at Sand Creek, killing over 200, forcing those survivors onto reservations. In 1886, former Union soldiers forced the Navajo into a similar trek as the Five Civilized Tribes in the Long Walk, wherein thousands perished on their way to reservation lands from their New Mexico homelands. Any tribal members that resisted were shot.

Driven by a so-called campaign of peace, President Ulysses Grant attempted a different approach, closing this era of removal and relocation. In a post-war effort, Grant instituted a ‘Peace Plan’ to “conquer through kindness.” This plan was called the Dawes General Allotment Act or the Dawes Act of 1887. The goal falsely presented as a plan to redistribute and protect land rights but turned out to be another process of denial of land rights. The Dawes Act revoked collective land ownership from the tribes and redistributed the land in smaller plots to individuals within the tribes. Tribal members would be given the deed to those plots of land after they had lived on that land for 25 years. Only after the 25 years of probation would the individuals receive the land titles, and some would even be granted citizenship.

This legislation had multiple issues. First, it denied the traditional communal land use that generally, Native Americans had practiced. Customarily, no individual owned land, but they utilized it as a collective unit. Second, it assumed that tribes were not capable of holding a land deed. This part of the act was intended to defend Natives from criminal land prospectors or sneaky investors, but it also assumed that tribal members were too inexperienced and unintelligent to recognize unfair deals. Next, much land was taken during the allotment era, never released by the government to Native Americans. Lastly the law withheld land titles for the span of a generation on purpose, to award the lands to the next generation of children that had most likely gone through Indian boarding schools meant to Americanize or assimilate Native American children into American culture. The last point leads to the next issue at hand – education.

Native American education in the U.S. during the 19th century was similar to other marginalized groups such as immigrant communities. For Native Americans, the outcome was much more detrimental to the culture. Education for these groups was tailored towards one goal – assimilation into American culture, also known as Americanization. This is the process of deemphasizing the original culture of a group and indoctrinating students to what was generally acceptable American culture. For example, language was a prevailing tactic to shift children towards American culture by forcing children to speak English rather than their Native language. For children of immigrants, this was problematic but practical, for they could remain bilingual, speaking one language at school and another at home. For Native Americans, this was cultural erasure, for the elder tribal members were continually being eradicated through warfare and the children were being forced to forget their native language. Through the Americanization process, the loss of Native American culture and custom was paramount. There was no home country where their languages and customs still existed because they were still in it. Their culture was just simply being erased.

The 19th century was extremely damaging to Native Americans – due to the breaking of treaties, erasure of culture, and outright genocide. The future of Native Americans was uncertain, and the next century would prove to be just as tumultuous.

THE 20TH CENTURY

In the next phase of Native American history, the government took yet another approach to relations with Native Americans. This shift was likely a response to Native participation during World War I (Treuer, 2019). First came the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 which officially recognized Native Americans as citizens, even though legally, under the 14th amendment, Natives already had birthright citizenship. Next was the Meriam Report, a comprehensive evaluation of Native reservation conditions, hospitals, schools, and other agencies. The push for the report came from Native American advocates that identified the failures of Native American policies and possibilities for progress. Men such as Peter Graves and John Collier called out the policy issues of the Dawes Act as well as the denial of religious freedoms that Natives endured.

Progress during the 1930s was difficult, especially during the economic crisis of the Great Depression. Nevertheless, Collier was able to negotiate the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, sometimes also called the Indian New Deal, because it was passed under President Roosevelt and his New Deal agenda. This act allowed for Native American lands to remain in their control and distributed amongst tribal members as well as the ability to self-govern. Although this was a step towards granting of freedoms, the IRA was problematic within Indian reservations for ambiguities.

Along with the IRA came the reintroduction of a colonial practice called blood quantum. This was known as the process of determining the fraction of Indian blood or ancestry. For instance, if one of your grandparents was full blood Choctaw, that made you ¼ Choctaw. This practice was reintroduced to verify access to tribal land ownership under the IRA. Blood quantum is still used today to determine tribal membership, although the requirements vary depending on the tribe.

Then, in 1956, the government took a different tactic in the implementation of the Indian Relocation Act. This legislation was passed to encourage young American Indians to leave reservations for urban areas to further the assimilation into American society. Financial assistance, vocational training, and other support was guaranteed for those that took up the opportunity. The result was often disastrous because the support that was guaranteed under this legislation was not consistently fulfilled. Many suffered from culture shock, homelessness, and poverty due to the failures of the policy.

While the IRA improved the lives of Native Americans to some degree, Native Americans still endured racial discrimination and hardships due to decades of mistreatment in America. The civil rights movements of the 1960s inspired many groups to push for equality and among those rose the Red Power movement. The movement was led by mostly young American Indians that sought policies to bring aid to Native American communities, maintain and protect land ownership, and reverse the termination of tribal recognition. Taking the cue of the African American protests of the time, participants of the Red Power movement engaged in non-violent protests and demonstrations to bring attention to their cause.

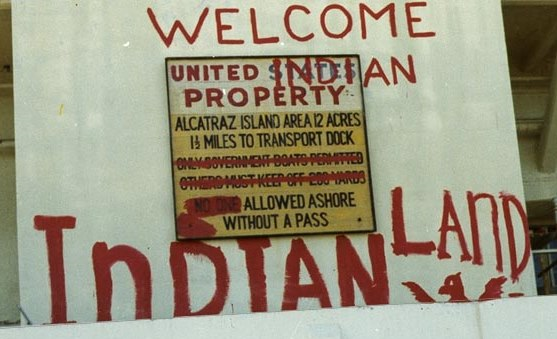

Additionally, the American Indian Movement (AIM) was founded in 1968. The supporters of this movement were largely the results of the failures of relocation. These Native Americans banned together in cities to create pan-Indian groups, this one growing into AIM. In November of 1969, AIM and other supporters carried out a 19-month long Occupation of Alcatraz. The federal facility lay dormant since 1963, and in a symbolic protest, Native American protesters made landfall on the island, claiming the land theirs for the taking, much like the European colonizers of the distant past. Occupants and supporters felt that reclaiming federal land from the government sent a clear message to the American public. For months, numerous Natives occupied the island, contacting the mainland primarily through a supply ship that would ferry people and supplies back and forth during occupation. Eventually the occupation ended due to the government forcing their removal, but the movement caught the brief attention of the media lending sympathy towards their cause. To this day, the graffiti on walls and structures painted by the occupants is still present.

By the 1970s and 80s, some real changes were on the horizon. This began with the Indian Education Act of 1972 that granted funds to increase graduation rates, curricular issues, and support services of Native Americans. These policies continued to expand, exemplified in the establishment of the first tribal college in the nation, the Navajo Community College. Some schools even began to implement lessons on Native American culture and history.

Additionally, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1978 under the Carter administration. For so long, Native Americans were compelled to suppress their culture and assimilate into American society. Those that chose to hold on to religious traditions had to do so in secret (Treuer, 2019). After this act was passed, Native Americans not only practiced their beliefs in the open but were able to pass their traditions down to the youth who never experienced them.

THE RECENT PAST

Beginning in the 1980s, the pseudo-reparations that Native Americans were awarded by the government came in the form of Indian Gaming operations. In a landmark case, California v. Cabazon, the Cabazon and Morongo Mission Indians won the right to run gaming facilities on tribal lands. After this ruling, gambling operations arose in other reservation lands across the nation. The late 80s witnessed legislation to tax and regulate Indian gaming, but otherwise, these establishments allowed tribes to generate wealth for their communities. Profits and distribution of profits vary from tribe to tribe. Currently, blood quantum continues to be the defining factor of tribal membership and to be a member after the rise of Indian gaming carried much more significance.

The 21st century continued to bring more cultural awareness to Americans. The myth of Columbus and his “discovery” has been broken, and the violence and political policies of the 19th and early 20th centuries are included in the historical narrative. Indigenous Day has been added to the calendar, the rediscovery of American Indian culture continues, and stereotypes of Native Americans are disappearing from logos and mascots. However, there is still much progress to be made. Native Americans still have remarkably low degrees in higher education, and an average low median income compared to other racial and ethnic groups. COVID-19 severely impacted reservation communities. Chief Joseph, a leader of the Nez Perce once said, "Good words do not last long unless they amount to something." As Americans, it is important that we stand by the promises of the Declaration of Independence, equality, life, liberty, and happiness.

SUMMARY

Native Americans once lived relatively peaceful. Once Europeans made initial contact, they identified indigenous peoples as inferior, savage, and unworthy of the land they cultivated for countless years. Once the U.S. was established, Americans embarked on a campaign of conquest, removal, and relocation of Native Americans. After tribes were decimated by disease and war, the U.S. government shifted policies to assimilation. Now, in the modern era, Native Americans are attempting to recover their culture and heritage, still working within U.S. institutions to reclaim tribal land and wealth.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- What kinds of societies existed in the Americas in pre-colonial times?

- Describe the initial interactions between Europeans and indigenous peoples. Where they positive or negative? Who benefitted from these interactions?

- How did American westward expansion impact Native American populations?

- What ways did Native Americans assert their civil liberties during the civil rights protests of the 20th century?

- How has the government sought to repair and restore relations with Native Americans in modern times?

TO MY FUTURE SELF

From the module, what information and new knowledge did I find interesting or useful? How do I plan to use this information and new knowledge in my personal and professional development and improvement?

REFERENCES

Columbus, C. (1492). Journal of Christopher Columbus, 1492. The American Yawp Reader. http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/the-new-world/journal-of-christopher-columbus/

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 1. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: A documentary history: Volume 2. (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Lee, J. (2014). Our fires still burn: The Native American experience viewer discussion guide. Vision Maker Media funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. https://visionmakermedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/edu_vdg_ofsb.pdf

Lepore, J. (1998). The name of war: King Philip’s war and the origins of American identity. Vintage.

Locke, J. & Wright, B. (2019). The American yawp. Stanford University Press. http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html.

Richter, D. K. (2001). Facing east from Indian country: A native history of early America. Harvard University Press.

Rothenberg, P. S. (2016). Race, class, and gender in the United States: An integrated study. (10th ed). Macmillan.

Takaki, R. (1993). A different mirror: A history of multicultural America. Back Bay Books.

Treuer, D. (2019). The heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the present. Riverhead Books.