6.2: Managing Culture Shock

- Page ID

- 55753

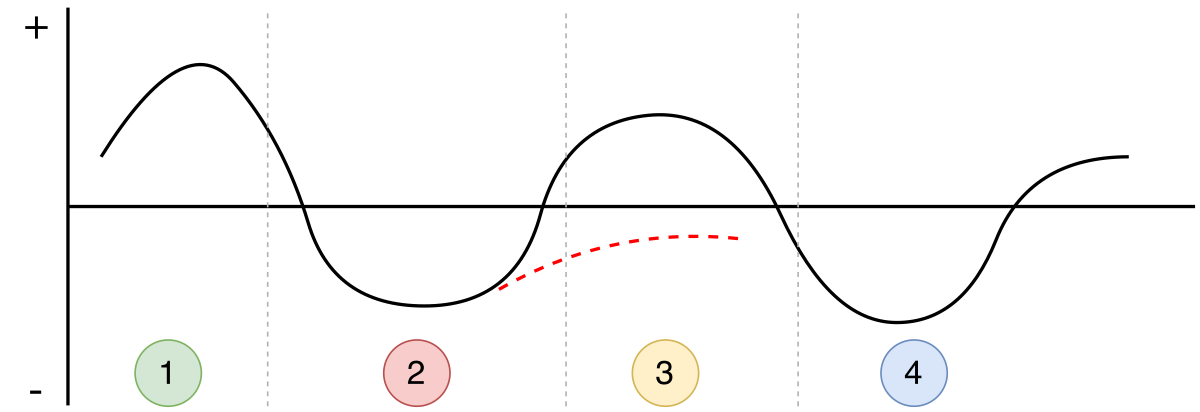

The experience of culture shock can range from mildly annoying to profoundly disturbing. Fortunately, many studies have been conducted and a few models have emerged that help explain the stages of culture shock. When we have a better understanding of this phenomenon, we are better suited to manage it. One of the best known models is The W-curve model, proposed by Gullahorn and Gullahorn (1963). The W shape represents the fluctuation of travelers' emotions when adapting to a new culture, and then when re-adapting to their home culture.

To understand this model, the vertical axis represents satisfaction, or happiness, and the horizontal axis represents time. The first stage, often called the honeymoon stage, happens right at the beginning of the journey. It represents the hope and excitement in anticipation of new experiences. For students who study abroad, the honeymoon stage signifies the start of the adventure. The long-awaited day has finally come! In this stage, the traveler may become infatuated with the language, food, people, and overall environment of the host culture. Stage two, the culture shock stage, is characterized by frustration and fatigue of not understanding the norms of the new culture. Common symptoms of the culture shock stage include: homesickness, feelings of helplessness, disorientation, isolation, depression, irritability, sleeping and eating disturbances, loss of focus, and more. As time progresses, the traveler begins to become more comfortable with the new environment. Navigating the new culture becomes easier, friendships and communities of support are established, the language and customs become more familiar. This adaptation to the new culture is the third stage, called the adjustment stage. The longer one stays in a new culture, the more one acclimatizes to it. These first three stages represent time spent in the new culture. This U-shape describes many of the early models of culture shock. The W-curve model expands on earlier models and recognizes that the return home can be marked by feeling let down and mental isolation. This fourth stage is referred to as reverse culture shock, or re-entry shock. Traveling can be profoundly enriching, even life-changing. Many students who have studied abroad claim it was the most significant thing they had done in their lives. When they first arrive home, they are eager to share their experiences with family and friends. This initial eagerness quickly fades as they have trouble relating the profound experience to those who stayed home. Further, they realize that nothing at home has changed and people grow tired of their stories and just want the traveler to return to "normal," meaning the way they were before the journey. The traveler has a new sense of identity that is not validated by their loved ones. Fortunately, through time, the traveler accepts their home culture and integrates their experiences into a new sense of self.

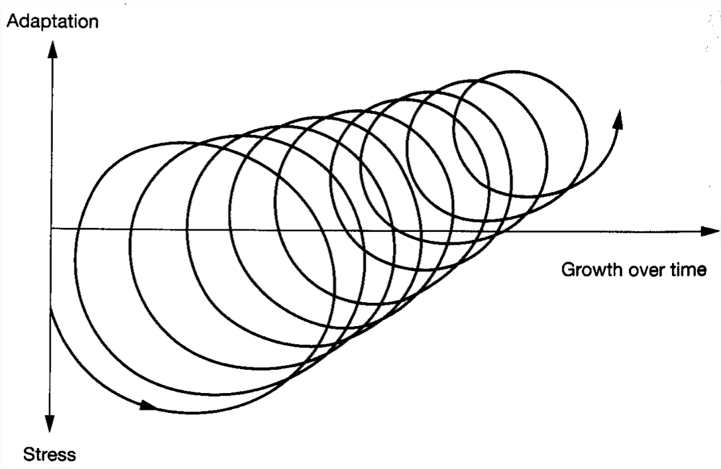

Some scholars have suggested other models for describing the process. Young Yun Kim (2005) sees adjustments happening in a cyclical pattern of stress – adaptation – growth. She sees stress as useful for an individual's growth and prefers "cultural adjustment" over "culture shock". It's also the case that acculturation is not just within the power of the individual. It also depends on the willingness of the host culture to accept (or not) the individual. A physician or engineer from abroad coming into a new country will likely be given a much better reception than poor immigrants; this can have a significant impact on the adjustment process. It can be the case as well that the co-cultures in the new country may be welcoming to the new arrival, if there are similarities which make acculturation smoother, such as national origin, sexual orientation, or professional affiliations. Adjusting to a new culture is facilitated by the presence of linguistic or cultural resources linked to the home culture, such as food markets, schools, and clubs.

As with all explanatory models, it is important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all model. Some people skip certain stages, experience them in a different order, or have a longer or shorter adjustment period than others. What researchers do agree upon is that it is natural to feel some degree of culture shock. Although most people recover from culture shock fairly quickly, a few find it to be profoundly disorienting, and take much longer to recover, particularly if they are unaware of the sources of the problem, and have no idea of how to counteract it. The following tips can help travelers manage the emotional roller coaster of culture shock.

Tips for Managing Culture Shock

One of the best remedies for managing culture shock starts with simply understand that culture shock exists. Culture shock can catch us by surprise. We feel emotions that we don't expect or are novel to us. A traveler once told me, "I don't know what's happening. I've always been really easy going, but lately I feel irritable all the time, even aggressive. This is not me." When we realize that culture shock exists, we have an explanation for the emotional turmoil caused by culture shock. If we don't know about culture shock, we are left wondering, "what's happening to me"," which can be profoundly unsettling. Many years ago, I was traveling through Honduras with a few other sojourners I met along the way. One afternoon, a young woman in our cohort just started crying. We asked her what happened and why she was crying. She just shook her head, and through her tears she said "Nothing happened, I don't know why I am crying!" In hindsight, it was clearly an effect of culture shock.

Culture shock by definition is the stress and anxiety we experience when we are in unfamiliar territory. Therefore, if we learn more about the host country, we may begin to have an understanding of the different norms and customs in our new environment. If we know we will be traveling, we should do our homework. There are countless guidebooks and websites that discuss different cultural tendencies exhibited by people of different nations. For example, cultureready.org has country specific information on greetings, communication style, gender issues, law and order, dress, socializing, business basics, and gift giving, to name just a few.

In the summer of 2005, I accepted a visiting professor position in Chengdu, China. Chengdu is a large city in western China. Very few locals spoke English, and the language difference between Mandarin and English is significant, making communication nearly impossible. Knowing that trying to bridge this language barrier is daunting, the resident director had students break into small groups and go to different sites within the city on the public busses on the first day. Once students arrived at their respective sites, they had some time to look around and then take a taxi to reconvene in the larger group for lunch. All students were given a small card with the name and address of the restaurant written in Chinese to hand to the taxi driver. This strategy was meant to give students an early opportunity to get out and experience the culture. In retrospect, this was an excellent strategy to help students manage culture shock. A common coping mechanism when confronting culture shock is to turn inward, and isolate oneself the host culture. Some people may choose to stay in their rooms all day instead of interacting with others. A better approach is to develop friendships or acquaintances with the locals. In Chengdu, there were certain locations called English corners, where people gathered to practice English. The American students who went to the English corners were surrounded by local Chinese people who invited them to their homes, took them out for meals, and showed them the hidden jewels of the city that they otherwise never would have encountered. To help meet locals, students who study abroad are encouraged to join campus clubs or community organizations that match their interests. When I taught in Spain for a semester, the study abroad organization set up intercambios between American study abroad students and local Spanish students. The stated purpose of these intercambios were for each party to practice the others' language, but they also served as a way for American students to meet locals and integrate into the local culture. I had a hard time meeting locals when I spent a week in Jamaica. I didn't like being perceived as just another white tourist, staying in the boundaries of an all-inclusive hotel. As a life-long soccer player, I started joining the local pick-up soccer games in the evenings. This was a perfect way to get to know local people outside of the oppressive relationship of the servers and the served.

When we enter an unfamiliar culture, we confront situations that we just don't understand. We may not understand the language people use when speaking to us. We might not understand the behavior of the locals, the significance of ceremonies, etc. To better manage culture shock, we need to learn to tolerate ambiguity. You can frustrate yourself to no end if you need to have explanations for everything happening all around you, all the time. By tolerating ambiguity, we become more comfortable with knowing that there is so much happening that we just don't understand, and that's okay. One of my favorite examples comes from traveling in rural Tibet. It was common for children to approach me and stick out their tongues at first greeting. I had no idea why this kept happening to me. Later I learned that this was a common greeting. According to Tibetan folklore, a cruel ninth-century Tibetan king had a black tongue, so people stick out their tongues to show that they are not like him (and aren't his reincarnation).

humans have a natural desire to reduce uncertainty in any given situation. When traveling through unfamiliar cultures, the increased levels of uncertainty can leave people feeling insecure. This insecurity is often projected outward and can manifest in disparaging the norms of the host culture. It is easy to compare our home culture with the unknown, and this can lead to ethnocentric thinking. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to evaluate other groups according to the values and standards of one's own ethnic group, especially with the conviction that one's own ethnic group is superior to the other groups (dictionary.com). The best advice for managing culture shock is be mindful of ethnocentrism and suspend ethnocentric evaluations.

Culture shock is stressful. Our attitude can profoundly influence our experience. To manage that stress, we need to cultivate a positive attitude.We can't always change our environment, but we can change how we react to it. It's important to have faith in yourself, in the essential goodwill of your hosts, and the positive outcome of the experience. Not everybody is out to get you. If someone laughs, it doesn't mean they are laughing at you. Of course we need to be careful when traveling abroad, but we don't need to be afraid. The most enriching experiences don't come from visiting historical landmarks, they come from deep, authentic connections we make with people along the way. Of course I will always remember visiting the Taj Mahal in India. But what warms my heart was sharing the long train journey with an Indian family, sharing foods and singing songs along the way.

Perhaps the International Institute for Peace trough Tourism offers the best attitudinal advice in the Credo of the Peaceful Traveler:

Grateful for the opportunity to travel and experience the world and because peace begins with the individual, I affirm my personal responsibility and commitment to:

Journey with an open mind and gentle heart

Accept with grace and gratitude the diversity I encounter

Revere and protect the natural environment which sustains all life

Appreciate all cultures I discover

Respect and thank my hosts for their welcome

Offer my hand in friendship to everyone I meet

Support travel services that share these views and act upon them and,

By my spirit, words and actions, encourage others to travel the world in peace

Advice for dealing with culture shock varies as much the symptoms and is dependent upon individual traits. Additional helpful tips include:

- Be flexible and try new things.

- Get involved in the things that you already like.

- Do not expect to adjust overnight.

- Process your thoughts and feelings.

- Use the resources available to help you handle the stress.

Contributors and Attributions

Intercultural Communication for the Community College, by Karen Krumrey-Fulks. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

Language and Culture in Context: A Primer on Intercultural Communication, by Robert Godwin-Jones. Provided by LibreTexts. License: CC-BY-NC