2.2: Articles of Confederation, Shays' Rebellion and the Road to the Constitution

- Page ID

- 134530

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)“The Articles of Confederation, if one considers the circumstances of the times, were a remarkable creation.”

–Rowland L. Young (1)

The United States has had more than one constitution in its history. Prior to the current U.S. Constitution written in 1787, there was the Articles of Confederation written in 1776 and 1777. Before we look at the details, let us familiarize ourselves with confederal government and how it differs from other forms. This idea is especially important given that when the Southern states seceded from the Union beginning in 1860, they formed a confederacy.

Confederal, Federal, and Unitary Governments

Political scientists often classify governmental systems into one of three types: confederal, federal, and unitary. Governments are placed into one of these categories based on the relative power distribution between the central government and the subordinate governments. In the United States, the subunits are called states, while other countries might have provinces, cantons, departments, laender, or something else.

- Confederal system is when the states are very powerful relative to the weak central government. Indeed, the central government usually only carries out those functions that the states deem can be more efficiently run from one point. The states retain all other powers. Currently, there are no individual countries that have confederal governments. Historically, confederacies tend not to survive—either because they are defeated by external enemies or because they fragment internally.

- Unitary system is when the central government is very powerful relative to the states. Often, the states exist merely as central government administrative units with little autonomy to conduct their own policies. The majority of the world’s governments are unitary. England, France, Israel, Sweden, and Japan are countries with unitary governments.

- Federal system has a power balance between the central government and the states (although in practice, the balance is often tilted in favor of the center). The United States, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, India, and Nigeria have this system. As a rule, large diverse countries tend to have federal governments.

The Articles of Confederation

Unifying the American colonies is an old concept. In 1697, William Penn proposed just such a union. In 1754, Benjamin Franklin put forward his Albany Plan of Union, which proposed a national legislature to raise a military when needed, make decisions on war and peace in North America, deal with disputed western lands, and levy taxes on the colonies. Franklin’s proposal was not accepted. When Franklin joined the Second Continental Congress in 1775, he put forward yet another proposal for an Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which was not taken up. After the Declaration of Independence, Congress appointed a committee to draft a confederation and chose John Dickinson to lead it. Using Franklin’s proposal as a starting point, the committee produced a document that gave the states much more power than Franklin had originally proposed. (2)

Dickinson’s committee wrote the Articles of Confederation on the assumption that the best way to preserve individual liberty was to fragment political power among the thirteen states. Congress submitted the Articles to the states to ratify in 1777, but disputes over western land claims delayed it from being formally adopted. Finally, in 1781, Maryland became the thirteenth state to ratify it. These Articles remained in effect until superseded by the Constitution.

The Confederal System’s Impact

Under the Articles of Confederation, the national government’s main legislative accomplishment was the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. It allowed territories to enter the Union as states on the same equal legal footing as the original thirteen states. In the territories that became Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, the Northwest Ordinance also prohibited slavery and provided public education.

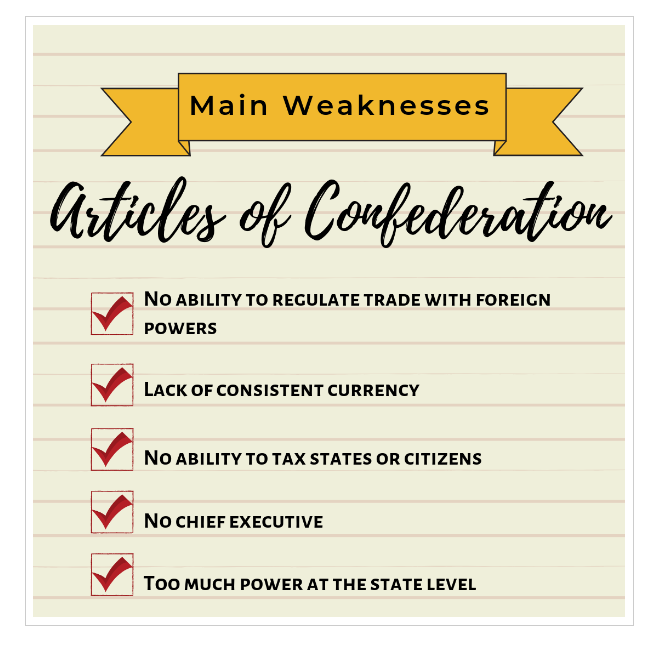

Following the Revolutionary War, the United States was in a very precarious economic, social, and diplomatic position. The government was unable to pay off war debts, such as loans from other countries, war bonds, and even IOU’s given to soldiers in lieu of pay. Trade was being choked off by state tariffs, and the money system was a mess. Farmers were especially hard hit by excess taxes, interstate tariffs, and generally lacked confidence in the money supply. Consequently, many people were losing their farms at bankruptcy auctions. Ultimately, farmers’ rebellions broke out up and down the Atlantic seaboard.

The largest such rebellion was Shays’ Rebellion (1786-87) in Massachusetts. Unable to make payments on their property and bitter with increased taxes and scarce money due to the state legislature’s policies in Boston, farmers peacefully petitioned the state legislature for redress. After the legislature refused to respond to their petitions, the farmers turned to mob violence to prevent debt hearings and their property from being seized for non-payment. The governor sent out a state militia. Daniel Shays, who had been a captain in the Revolutionary War, organized a rebellion. Shays’ Rebellion pointed out many of the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation, and was much discussed at a convention convened in Philadelphia. As historian Joseph Ellis has written, “The ultimate irony of Shays’ Rebellion is that what began as a rural protest against centralized government actually ended up strengthening the advocates for a new U.S. Constitution, which consolidated political power at the federal level, in precisely the fashion that the rebels regarded as a betrayal of the American Revolution.” (4)

The Constitutional Convention

Largely due to the efforts of people like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison—and because of the turmoil under the Articles of Confederation—Congress called on the states to send delegates to Philadelphia in May 1787. The reason for the gathering was “for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.” Every state except Rhode Island sent delegates to what we now know as the Constitutional Convention. Madison and Hamilton attended, as did George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert Morris, Charles Pinckney, and others. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams did not attend, because they were representing the United States in Paris and London, respectively. Patrick Henry did not participate because he “smelt a rat,” and opposed the Constitution once it was written. (5)

Of the original seventy-four delegates picked by the states, fifty-five actually attended the convention in Philadelphia. Some stayed away due to conscience, others because they were busy with other matters. By September 17, 1787, when the final draft was approved, only forty-two delegates were left. Three of those—Edmund Randolph, George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry—could not bring themselves to sign the Constitution. In the end, thirty-nine delegates signed what is now the current U.S. Constitution.

References

- Rowland L. Young, “The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union,” American Bar Association Journal. November, 1977. Page 1575.

- Thomas Wendel, “The Articles of Confederation,” National Review. July 10, 1981. Page 769.

- George William Van Cleve, We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017. Page 54. All details in the next four paragraphs come from this source.

- Joseph J. Ellis, “Dispelling the Myths Surrounding Shays Rebellion,” Commonwealth: Nonprofit Journal of Politics, Ideas, & Civic Life. December 1, 2002.

- Christopher Collier and James Lincoln Collier, Decision in Philadelphia. New York: Ballantine Books, 1986. P. 74.

Media Attributions

- Articles of Confed © soukup is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license