1.5: Organizational Change

- Page ID

- 114490

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Essential Questions

- What is the process of culture change in an organization?

- What are factors that create the case for organizations to change?

- What are ways in which a prospective employee can adapt to a new culture?

- What are theories that explain how we respond to change?

- What are the skills that allow us to adapt to change more readily and successfully?

Creating Culture Change

As emphasized throughout this chapter, culture is a product of its founder’s values, its history, and collective experiences. Hence, culture is part of a company’s DNA and is resistant to change efforts. Unfortunately, many organizations realize that their current culture constitutes a barrier against organizational productivity and performance. Particularly when there is a mismatch between an organization’s values and the demands of its environment, changing the culture becomes the key to the company turnaround.

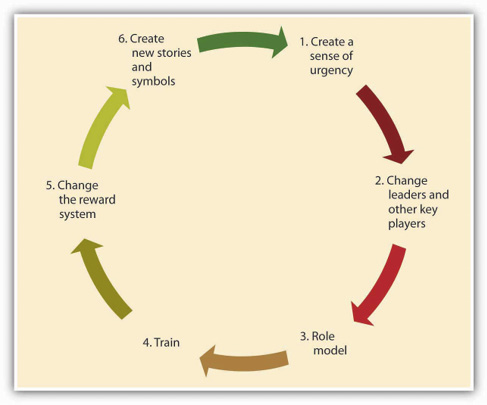

Achieving culture change is challenging, and there are many companies that ultimately fail in this mission. Research and case studies of companies that successfully changed their culture indicate that the following six steps increase the chances of success (Schein, 1990).

Creating a Sense of Urgency

For the change effort to be successful, it is important to communicate the need for change to employees. One way of doing this is to create a sense of urgency on the part of employees, explaining to them why changing the fundamental way in which business is done is so important. In successful culture change efforts, leaders communicate with employees and present a case for culture change as the essential element that will lead the company to eventual success. As an example, consider the situation at IBM in 1993 when Lou Gerstner was brought in as CEO and chairman. After decades of dominating the market for mainframe computers, IBM was rapidly losing market share to competitors, and its efforts to sell personal computers—the original PC—were seriously undercut by cheaper “clones.” In the public’s estimation, the name IBM had become associated with obsolescence. Gerstner recalls that the crisis IBM was facing became his ally in changing the organization’s culture. Instead of spreading optimism about the company’s future, he used the crisis at every opportunity to get buy-in from employees (Gerstner, 2002) (see Figure 1).

Changing Leaders and Other Key Players

A leader’s vision is an important factor that influences how things are done in an organization. Thus, culture change often follows changes at the highest levels of the organization. Moreover, to implement the change effort quickly and efficiently, a company may find it helpful to remove managers and other powerful employees who are acting as a barrier to change. Because of political reasons, self-interest, or habits, managers may create powerful resistance to change efforts. In such cases, replacing these positions with employees and managers giving visible support to the change effort may increase the likelihood that the change effort succeeds. For example, when Robert Iger replaced Michael Eisner as CEO of the Walt Disney Company, one of the first things he did was to abolish the central planning unit, which was staffed by people close to ex-CEO Eisner. This department was viewed as a barrier to creativity at Disney and its removal from the company was helpful in ensuring the innovativeness of the company culture (McGregor, et. al., 2007).

Role Modeling

Role modeling is the process by which employees modify their own beliefs and behaviors to reflect those of the leader (Kark & Van Dijk, 2007). CEOs can model the behaviors that are expected of employees to change the culture because these behaviors will trickle down to lower-level employees. For example, when Robert Iger took over Disney, to show his commitment to innovation, he personally became involved in the process of game creation, attended summits of developers, and gave feedback to programmers about the games. Thus, he modeled his engagement in the idea creation process. In contrast, the modeling of inappropriate behavior from the top will lead to the same behavior trickling down to lower levels. A recent example to this type of role modeling is the scandal involving Hewlett-Packard board members. In 2006, when board members were suspected of leaking confidential company information to the press, the company’s top-level executives hired a team of security experts to find the source of the leak. The investigators sought the phone records of board members, looking for links to journalists. For this purpose, they posed as board members and called phone companies to obtain itemized home phone records of board members and journalists. When the investigators’ methods came to light, HP’s chairman and four other top executives faced criminal and civil charges. When such behavior is modeled at top levels, it is likely to have an adverse effect on the company culture (Barron, 2007).

Training

Well-crafted training programs may be instrumental in bringing about culture change by teaching employees the new norms and behavioral styles. For example, after the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated on reentry from a February 2003 mission, NASA decided to change its culture to become more safety sensitive and minimize decision-making errors that lead to unsafe behaviors. The change effort included training programs in team processes and cognitive bias awareness. Similarly, when auto repairer Midas felt the need to change its culture to be more committed to customers, they developed a program to train employees to be more familiar with customer emotions and connect better with them. Customer reports have been overwhelmingly positive in stores that underwent this training.1

Changing the Reward System

The criteria with which employees are rewarded and punished have a powerful role in determining the cultural values of an organization. Switching from a commission-based incentive structure to a straight salary system may be instrumental in bringing about customer focus among sales employees. Moreover, by rewarding and promoting employees who embrace the company’s new values and promoting these employees, organizations can make sure that changes in culture have a lasting effect. If the company wants to develop a team-oriented culture where employees collaborate with one another, then using individual-based incentives may backfire. Instead, distributing bonuses to intact teams might be more successful in bringing about culture change.

Creating New Symbols and Stories

Finally, the success of the culture change effort may be increased by developing new rituals, symbols, and stories. Continental Airlines is a company that successfully changed its culture to be less bureaucratic and more team-oriented in 1990s. One of the first things management did to show employees that they really meant to abolish many of the company’s detailed procedures and create a culture of empowerment was to burn the heavy 800-page company policy manual in their parking lot. The new manual was only 80 pages. This action symbolized the upcoming changes in the culture and served as a powerful story that circulated among employees. Another early action was redecorating waiting areas and repainting all their planes, again symbolizing the new order of things (Higgins & McAllester, 2004). By replacing the old symbols and stories, the new symbols and stories will help enable the culture change and ensure that the new values are communicated.

Key Takeaway

Organizations need to change their culture to respond to changing conditions in the environment, to remain competitive, and to avoid complacency or stagnation. Culture change often begins by the creation of a sense of urgency. Next, a change of leaders and other key players may enact change and serve as effective role models of new behavior. Training can also be targeted toward fostering these new behaviors. Reward systems are changed within the organization. Finally, the organization creates new stories and symbols. Successful culture change requires managers that are proficient at all of the P-O-L-C functions. Creating and communicating a vision is part of planning; leadership and role modeling are part of leading; designing effective reward systems is part of controlling; all of which combine to influence culture, a facet of organizing.

Source: 1BST to guide culture change effort at NASA. (2004 June). Professional Safety, 49, 16; J. B. (2001, June). The Midas touch. Training, 38, 26.

Developing Your Personal Skills: Learning to Fit In

How do you find out about a company’s culture before you join? Here are several tips that will allow you to more accurately gauge the culture of a company you are interviewing with.

First, do your research. Talking to friends and family members who are familiar with the company, doing an online search for news articles about the company, browsing the company’s Web site, and reading its mission statement would be a good start.

Second, observe the physical environment. Do people work in cubicles or in offices? What is the dress code? What is the building structure? Do employees look happy, tired, or stressed? The answers to these questions are all pieces of the puzzle.

Third, read between the lines. For example, the absence of a lengthy employee handbook or detailed procedures might mean that the company is more flexible and less bureaucratic.

Fourth, reflect on how you are treated. The recruitment process is your first connection to the company. Were you treated with respect? Do they maintain contact with you or are you being ignored for long stretches at a time?

Fifth, ask questions. What happened to the previous incumbent of this job? What does it take to be successful in this firm? What would their ideal candidate for the job look like? The answers to these questions will reveal a lot about the way they do business.

Finally, listen to your gut. Your feelings about the place in general, and your future manager and coworkers in particular, are important signs that you should not ignore (Daniel & Brandon, 2006; Sacks, 2005).

You’ve Got a New Job! Now How Do You Get on Board?

- Gather information. Try to find as much about the company and the job as you can before your first day. After you start working, be a good observer, gather information, and read as much as you can to understand your job and the company. Examine how people are interacting, how they dress, and how they act, in order to avoid behaviors that might indicate to others that you are a misfit.

- Manage your first impression. First impressions may endure, so make sure that you dress properly, are friendly, and communicate your excitement to be a part of the team. Be on your best behavior!

- Invest in relationship development. The relationships you develop with your manager and with coworkers will be essential for you to adjust to your new job. Take the time to strike up conversations with them. If there are work functions during your early days, make sure not to miss them!

- Seek feedback. Ask your manager or coworkers how well you are doing and whether you are meeting expectations. Listen to what they are telling you and listen to what they are not saying. Then, make sure to act on any suggestions for improvement—you may create a negative impression if you consistently ignore the feedback you receive.

- Show success early on. To gain the trust of your new manager and colleagues, you may want to establish a history of success early. Volunteer for high-profile projects where you will be able to demonstrate your skills. Alternatively, volunteer for projects that may serve as learning opportunities or that may put you in touch with the key people in the company.

Key Takeaway

There are a number of ways to learn about an organization’s culture before you formally join it. Take the time to consider whether the culture you are observing seems like the right fit for you. Once you get a job, you can do key things to maximize your onboarding success.

Why Do Organizations Change?

Organizational change is the movement of an organization from one state of affairs to another. A change in the environment often requires change within the organization operating within that environment. Change in almost any aspect of a company’s operation can be met with resistance, and different cultures can have different reactions to both the change and the means to promote the change. To better facilitate necessary changes, several steps can be taken that have been proved to lower the anxiety of employees and ease the transformation process. Often, the simple act of including employees in the change process can drastically reduce opposition to new methods. In some organizations, this level of inclusion is not possible, and instead organizations can recruit a small number of opinion leaders to promote the benefits of coming changes.

Organizational change can take many forms. It may involve a change in a company’s structure, strategy, policies, procedures, technology, or culture. The change may be planned years in advance or may be forced on an organization because of a shift in the environment. Organizational change can be radical and swiftly alter the way an organization operates, or it may be incremental and slow. In any case, regardless of the type, change involves letting go of the old ways in which work is done and adjusting to new ways.

Therefore, fundamentally, it is a process that involves effective people management.

Managers carrying out any of the P-O-L-C functions often find themselves faced with the need to manage organizational change effectively. Oftentimes, the planning process reveals the need for a new or improved strategy, which is then reflected in changes to tactical and operational plans. Creating a new organizational design (the organizing function) or altering the existing design entails changes that may affect from a single employee up to the entire organization, depending on the scope of the changes. Effective decision making, a Leadership task, takes into account the change-management implications of decisions, planning for the need to manage the implementation of decisions. Finally, any updates to controlling systems and processes will potentially involve changes to employees’ assigned tasks and performance assessments, which will require astute change management skills to implement. In short, change management is an important leadership skill that spans the entire range of P-O-L-C functions.

Workplace Demographics

Organizational change is often a response to changes to the environment. For example, agencies that monitor workplace demographics such as the U.S. Department of Labor and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development have reported that the average age of the U.S. workforce will increase as the baby boom generation nears retirement age and the numbers of younger workers are insufficient to fill the gap (Lerman, R. I. and Schmidt, S. R., 2006). What does this mean for companies? Organizations may realize that as the workforce gets older, the types of benefits workers prefer may change. Work arrangements such as flexible work hours and job sharing may become more popular as employees remain in the workforce even after retirement. It is also possible that employees who are unhappy with their current work situation will choose to retire, resulting in a sudden loss of valuable knowledge and expertise in organizations. Therefore, organizations will have to devise strategies to retain these employees and plan for their retirement. Finally, a critical issue is finding ways of dealing with age-related stereotypes which act as barriers in the retention of these employees.

Technology

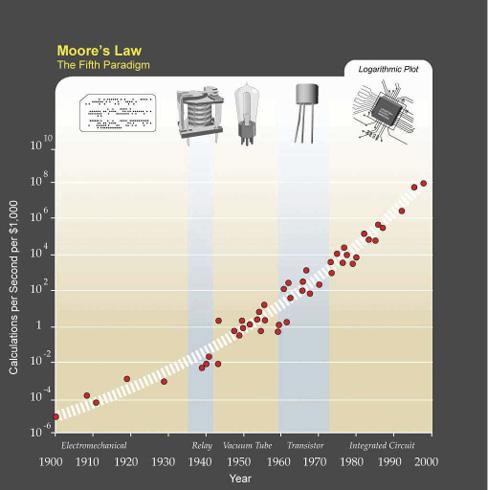

Sometimes change is motivated by rapid developments in technology. Moore’s law (a prediction by Gordon Moore, cofounder of Intel) dictates that the overall complexity of computers will double every 18 months with no increase in cost (Anonymous, 2008). Such change is motivating corporations to change their technology rapidly. Sometimes technology produces such profound developments that companies struggle to adapt. A recent example is from the music industry. When music CDs were first introduced in the 1980s, they were substantially more appealing than the traditional LP vinyl records. Record companies were easily able to double the prices, even though producing CDs cost a fraction of what it cost to produce LPs. For decades, record-producing companies benefited from this status quo. Yet when peer-to-peer file sharing through software such as Napster and Kazaa threatened the core of their business, companies in the music industry found themselves completely unprepared for such disruptive technological changes. Their first response was to sue the users of file-sharing software, sometimes even underage kids. They also kept looking for a technology that would make it impossible to copy a CD or DVD, which has yet to emerge. Until Apple’s iTunes came up with a new way to sell music online, it was doubtful that consumers would ever be willing to pay for music that was otherwise available for free (albeit illegally so). Only time will tell if the industry will be able to adapt to the changes forced on it (Lasica, J. D., 2005) (Figure 2)

Globalization

Globalization is another threat and opportunity for organizations, depending on their ability to adapt to it. Because of differences in national economies and standards of living from one country to another, organizations in developed countries are finding that it is often cheaper to produce goods and deliver services in less developed countries. This has led many companies to outsource (or “offshore”) their manufacturing operations to countries such as China and Mexico. In the 1990s, knowledge work was thought to be safe from outsourcing, but in the 21st century we are also seeing many service operations moved to places with cheaper wages. For example, many companies have outsourced software development to India, with Indian companies such as Wipro and Infosys emerging as global giants. Given these changes, understanding how to manage a global workforce is a necessity. Many companies realize that outsourcing forces them to operate in an institutional environment that is radically different from what they are used to at home. Dealing with employee stress resulting from jobs being moved overseas, retraining the workforce, and learning to compete with a global workforce on a global scale are changes companies are trying to come to grips with.

Changes in the Market Conditions

Market changes may also create internal changes as companies struggle to adjust. For example, as of this writing, the airline industry in the United States is undergoing serious changes. Demand for air travel was reduced after the September 11 terrorist attacks. At the same time, the widespread use of the Internet to book plane travels made it possible to compare airline prices much more efficiently and easily, encouraging airlines to compete primarily based on cost. This strategy seems to have backfired when coupled with the dramatic increases in the cost of fuel that occurred beginning in 2004. As a result, by mid-2008, airlines were cutting back on amenities that had formerly been taken for granted for decades, such as the price of a ticket including meals, beverages, and checking luggage. Some airlines, such as Delta and Northwest Airlines, merged to stay in business.

How does a change in the environment create change within an organization? Environmental change does not automatically change how business is done. Whether the organization changes or not in response to environmental challenges and threats depends on the decision makers’ reactions to what is happening in the environment.

Growth

It is natural for once small start-up companies to grow if they are successful. An example of this growth is the evolution of the Widmer Brothers Brewing Company, which started as two brothers brewing beer in their garage to becoming the 11th largest brewery in the United States. This growth happened over time as the popularity of their key product—Hefeweizen—grew in popularity and the company had to expand to meet demand growing from the two founders to the 11th largest brewery in the United States by 2008. In 2007, Widmer Brothers merged with Redhook Ale Brewery. Anheuser-Busch continues to have a minority stake in both beer companies. So, while 50% of all new small businesses fail in their first year (Get ready, 2008), those that succeed often evolve into large, complex organizations over time (Figure 3).

Poor Performance

Change can also occur if the company is performing poorly and if there is a perceived threat from the environment. In fact, poorly performing companies often find it easier to change compared with successful companies. Why? High performance actually leads to overconfidence and inertia. As a result, successful companies often keep doing what made them successful in the first place. When it comes to the relationship between company performance and organizational change, the saying “nothing fails like success” may be fitting. For example, Polaroid was the number one producer of instant films and cameras in 1994. Less than a decade later, the company filed for bankruptcy, unable to adapt to the rapid advances in one-hour photo development and digital photography technologies that were sweeping the market. Successful companies that manage to change have special practices in place to keep the organization open to changes. For example, Finnish cell phone maker Nokia finds that it is important to periodically change the perspective of key decision makers. For this purpose, they rotate heads of businesses to different posts to give them a fresh perspective. In addition to the success of a business, change in a company’s upper-level management is a motivator for change at the organization level. Research shows that long-tenured CEOs are unlikely to change their formula for success. Instead, new CEOs and new top management teams create change in a company’s culture and structure (Barnett, W. P. and Carroll, G. R., 1995; Boeker, W., 1997; Deutschman, A., 2005).

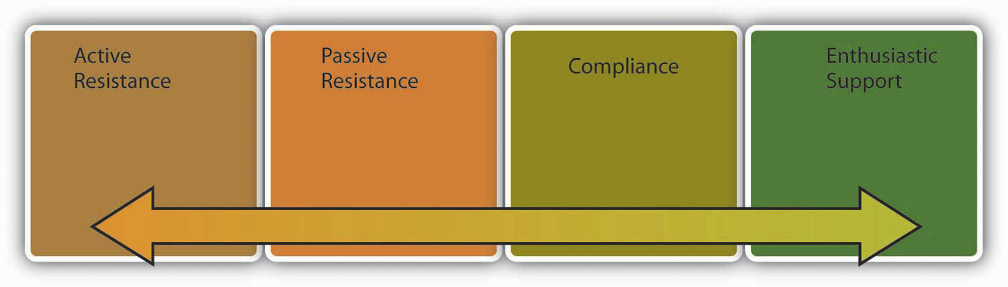

Resistance to Change

Changing an organization is often essential for a company to remain competitive. Failure to change may influence the ability of a company to survive. Yet employees do not always welcome changes in methods. According to a 2007 survey conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), employee resistance to change is one of the top reasons change efforts fail. In fact, reactions to organizational change may range from resistance to compliance to enthusiastic support of the change, with the latter being the exception rather than the norm (Anonymous, 2007; Huy, Q. N., 1999).

Active resistance is the most negative reaction to a proposed change attempt. Those who engage in active resistance may sabotage the change effort and be outspoken objectors to the new procedures. In contrast, passive resistance involves being disturbed by changes without necessarily voicing these opinions. Instead, passive resisters may dislike the change quietly, feel stressed and unhappy, and even look for a new job without necessarily bringing their concerns to the attention of decision makers. Compliance, however, involves going along with proposed changes with little enthusiasm. Finally, those who show enthusiastic support are defenders of the new way and actually encourage others around them to give support to the change effort as well (Figure 4).

To be successful, any change attempt will need to overcome resistance on the part of employees. Otherwise, the result will be loss of time and energy as well as an inability on the part of the organization to adapt to the changes in the environment and make its operations more efficient. Resistance to change also has negative consequences for the people in question. Research shows that when people react negatively to organizational change, they experience negative emotions, use sick time more often, and are more likely to voluntarily leave the company (Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., and Prussia, G. E., 2008). These negative effects can be present even when the proposed change clearly offers benefits and advantages over the status quo.

The following is a dramatic example of how resistance to change may prevent improving the status quo. Have you ever wondered why the keyboards we use are shaped the way they are? The QWERTY keyboard, named after the first six letters in the top row, was actually engineered to slow us down. When the typewriter was first invented in the 19th century, the first prototypes of the keyboard would jam if the keys right next to each other were hit at the same time. Therefore, it was important for manufacturers to slow typists down. They achieved this by putting the most commonly used letters to the left-hand side and scattering the most frequently used letters all over the keyboard. Later, the issue of letters being stuck was resolved. In fact, an alternative to the QWERTY developed in the 1930s by educational psychologist August Dvorak provides a much more efficient design and allows individuals to double traditional typing speeds. Yet the Dvorak keyboard never gained wide acceptance. The reasons? Large numbers of people resisted the change. Teachers and typists resisted because they would lose their specialized knowledge. Manufacturers resisted due to costs inherent in making the switch and the initial inefficiencies in the learning curve (Diamond, J., 2005). In short, the best idea does not necessarily win, and changing people requires understanding why they resist (Figure 5).

Do People Resist Change?

Disrupted Habits

People often resist change for the simple reason that change disrupts our habits. When you hop into your car for your morning commute, do you think about how you are driving? Most of the time probably not, because driving generally becomes an automated activity after a while. You may sometimes even realize that you have reached your destination without noticing the roads you used or having consciously thought about any of your body movements. Now imagine you drive for a living and even though you are used to driving an automatic car, you are forced to use a stick shift. You can most likely figure out how to drive a stick, but it will take time, and until you figure it out, you cannot drive on auto pilot. You will have to reconfigure your body movements and practice shifting until you become good at it. This loss of a familiar habit can make you feel clumsy; you may even feel that your competence as a driver is threatened. For this simple reason, people are sometimes surprisingly outspoken when confronted with simple changes such as updating to a newer version of a particular software or a change in their voice mail system.

Personality

Some people are more resistant to change than others. Recall that one of the Big Five personality traits is Openness to Experience; obviously, people who rank high on this trait will tend to accept change readily. Research also shows that people who have a positive self-concept are better at coping with change, probably because those who have high self-esteem may feel that whatever the changes are, they are likely to adjust to it well and be successful in the new system. People with a more positive self-concept and those who are more optimistic may also view change as an opportunity to shine as opposed to a threat that is overwhelming. Finally, risk tolerance is another predictor of how resistant someone will be to stress. For people who are risk avoidant, the possibility of a change in technology or structure may be more threatening (Judge, T. A., et. al., 2000; Wanberg, C. R., and Banas, J. T., 2000).

Feelings of Uncertainty

Change inevitably brings feelings of uncertainty. You have just heard that your company is merging with another. What would be your reaction? Such change is often turbulent, and it is often unclear what is going to happen to each individual. Some positions may be eliminated. Some people may see a change in their job duties. Things may get better—or they may get worse. The feeling that the future is unclear is enough to create stress for people because it leads to a sense of lost control (Ashford, S. J., Lee, C. L., and Bobko, P., 1989; Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., and Prussia, G. E., 2008) (Figure 6).

Fear of Failure

People also resist change when they feel that their performance may be affected under the new system. People who are experts in their jobs may be less than welcoming of the changes because they may be unsure whether their success would last under the new system. Studies show that people who feel that they can perform well under the new system are more likely to be committed to the proposed change, while those who have lower confidence in their ability to perform after changes are less committed (Herold, D. M., Fedor, D. B., and Caldwell, S., 2007).

Personal Impact of Change

It would be too simplistic to argue that people resist all change, regardless of its form. In fact, people tend to be more welcoming of change that is favorable to them on a personal level (such as giving them more power over others or change that improves quality of life such as bigger and nicer offices). Research also shows that commitment to change is highest when proposed changes affect the work unit with a low impact on how individual jobs are performed (Fedor, D. M., Caldwell, S., and Herold, D. M., 2006).

Prevalence of Change

Any change effort should be considered within the context of all the other changes that are introduced in a company. Does the company have a history of making short-lived changes? If the company structure went from functional to product-based to geographic to matrix within the past five years and the top management is in the process of going back to a functional structure again, a certain level of resistance is to be expected because employees are likely to be fatigued as a result of the constant changes. Moreover, the lack of a history of successful changes may cause people to feel skeptical toward the newly planned changes. Therefore, considering the history of changes in the company is important to understanding why people resist. Another question is, how big is the planned change? If the company is considering a simple switch to a new computer program, such as introducing Microsoft Access for database management, the change may not be as extensive or stressful compared with a switch to an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system such as SAP or PeopleSoft, which require a significant time commitment and can fundamentally affect how business is conducted (Labianca, G., Gray, B., and Brass, D. J., 2000; Rafferty, A. E., and Griffin, M. A., 2006).

Perceived Loss of Power

One other reason people may resist change is that change may affect their power and influence in the organization. Imagine that your company moved to a more team-based structure, turning supervisors into team leaders. In the old structure, supervisors were in charge of hiring and firing all those reporting to them. Under the new system, this power is given to the team. Instead of monitoring the progress the team is making toward goals, the job of a team leader is to provide support and mentoring to the team in general and ensure that the team has access to all resources to be effective. Given the loss in prestige and status in the new structure, some supervisors may resist the proposed changes even if it is better for the organization to operate around teams.

In summary, there are many reasons individuals resist change, which may prevent an organization from making important changes.

Is All Resistance Bad?

Resistance to change may be a positive force in some instances. In fact, resistance to change is a valuable feedback tool that should not be ignored. Why are people resisting the proposed changes? Do they believe that the new system will not work? If so, why not? By listening to people and incorporating their suggestions into the change effort, it is possible to make a more effective change. Some of a company’s most committed employees may be the most vocal opponents of a change effort. They may fear that the organization they feel such a strong attachment to is being threatened by the planned change effort and the change will ultimately hurt the company. In contrast, people who have less loyalty to the organization may comply with the proposed changes simply because they do not care enough about the fate of the company to oppose the changes. As a result, when dealing with those who resist change, it is important to avoid blaming them for a lack of loyalty (Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., and D’Amelio, A., 2008).

Key Takeaway

Organizations change in response to changes in the environment and in response to the way decision makers interpret these changes. When it comes to organizational change, one of the biggest obstacles is resistance to change. People resist change because change disrupts habits, conflicts with certain personality types, causes a fear of failure, can have potentially negative effects, can result in a potential for loss of power, and, when done too frequently, can exhaust employees.

Building Your Change Management Skills

Overcoming Resistance to Your Proposals

You feel that a change is needed. You have a great idea. But people around you do not seem convinced. They are resisting your great idea. How do you make change happen?

- Listen to naysayers. You may think that your idea is great, but listening to those who resist may give you valuable ideas about why it may not work and how to design it more effectively.

- Is your change revolutionary? If you are trying to change dramatically the way things are done, you will find that resistance is greater. If your proposal involves incrementally making things better, you may have better luck.

- Involve those around you in planning the change. Instead of providing the solutions, make them part of the solution. If they admit that there is a problem and participate in planning a way out, you would have to do less convincing when it is time to implement the change.

- Assess your credibility. When trying to persuade people to change their ways, it helps if you have a history of suggesting implementable changes. Otherwise, you may be ignored or met with suspicion. This means you need to establish trust and a history of keeping promises over time before you propose a major change.

- Present data to your audience. Be prepared to defend the technical aspects of your ideas and provide evidence that your proposal is likely to work.

- Appeal to your audience’s ideals. Frame your proposal around the big picture. Are you going to create happier clients? Is this going to lead to a better reputation for the company? Identify the long-term goals you are hoping to accomplish that people would be proud to be a part of.

- Understand the reasons for resistance. Is your audience resisting because they fear change? Does the change you propose mean more work for them? Does it affect them in a negative way? Understanding the consequences of your proposal for the parties involved may help you tailor your pitch to your audience (McGoon, 1995; Michelman, 2007; Stanley, 2002).

Key Takeaway

There are several steps you can take to help you overcome resistance to change. Many of them share the common theme of respecting those who are resistant so you can understand and learn from their concerns.

How We Change

Goal Setting

As we discussed, our emotional intelligence is the cornerstone for career success. Part of self-management is knowing ourselves and being able to set goals based on understanding our own needs and wants.

Many people end up adrift in life, with no real goal or purpose, which can show lack of self-management. Some people are happy this way, but most people would prefer to have goals that can set the direction for their life. It is similar to going on a road trip without a map or GPS. You might have fun for a while, going where the wind takes you, but at some point you may like to see specific things or stop at certain places, which creates the need for GPS. What happens if you have been driving aimlessly for a while but decide what you want to see is five hundred miles back the other way? A goal would have helped you plan the steps along the way in your trip. Goals are the GPS for your life. Research done by Locke et al. in the late 1960s shows a direct connection between goal setting and high achievement.Locke, Edwin A., Shaw, Karyll N., Saari, Lise M., & Latham, Gary P. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90(1), 125–52. One of the most popular methods to setting goals is called the SMART philosophy. This includes the following “steps” or aspects to goal setting:

- Specific. First, the goals need to be specific. Rather than saying, “I want to be a better person,” try a goal such as “volunteer two hours per week.” The more specific the goal, the more we are able to determine if we were successful in that goal. In other words, being specific allows us to be very clear about what we want to achieve. This clarity helps us understand specifically what we need to do in order to achieve the goal.

- Measurable. The goal must be measured. At the end of the time period, you should be able to say, “Yes, I met that goal.” For example, “increase my sales” isn’t measureable. Saying something such as, “I will increase my sales by 10 percent over the next two years,” is very specific and measureable. At the end of two years, you can look at how well you have performed and compare your goal with the result.

- Attainable. The goals should be something we can achieve. We must either already have or be able to develop the attitudes, skills, and abilities in order to achieve the goal. This doesn’t mean you need these skills right now, but it does mean over time you should be able to develop them. For example, if my goal is to become a light aircraft pilot, but I am afraid of flying, it may mean I am not willing (or able) to develop the skills and abilities in order to achieve this goal. So this goal would not be attainable and I should choose another one.

- Realistic. The goal that is set must be something you are willing and able to work toward. The goal cannot be someone else’s goal. For example, earning a business degree because your parents want you to may not be compelling enough to follow through with that goal. The goal should be realistic in terms of your abilities and willingness to work toward the goal. If I decided I wanted to be a WNBA player, this is probably not a realistic goal for me. I am too old; I am five feet two inches and not really willing to put in the time to get better at basketball. So as a result, I would likely not achieve this goal.

- Time-oriented. There should always be a timeframe attached to a specific goal. Most individuals will have longer-term and shorter-term goals. For example, a long-term goal might be to manage a medical lab. In order to meet this longer-term goal, shorter-term goals might include the following:

- Earn a medical lab technology degree

- Obtain employment as a medical lab tech

- Develop skills by attending two conferences per year

- Develop positive relationship with coworkers and supervisor by using emotional intelligence skills

Within all of our goals, there are shorter-term objectives. Objectives are the shorter-term goals we must do in order to accomplish our bigger goals. For example, possible objectives for two of the goals mentioned previously might be the following:

- Earn a medical lab technology degree

- Take three courses per quarter to finish in two years

- Study at least three to six hours per day to earn a 3.5 GPA or higher

- See my advisor once per quarter

- Slot one night per week for social time, but focus on studies the rest of the time

- Obtain employment as a medical lab tech

- Do an internship in the last quarter of school

- Create a dynamic resume

- Obtain recommendations from instructors

- Attend the quarterly medical lab networking event while in school

Another effective strategy in goal setting is writing goals down. Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal-setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Why is this so important? First, you are forced to clarify and think about specific goals using SMART objectives. Second, writing goals down can turn your direction into the right one, and you will be less likely to be sidetracked by other things. Writing goals down and revisiting them often can also provide an outlet for helping you celebrate meeting a certain objective. In our previous example, by writing these things down, we are able to celebrate the smaller successes such as earning a 3.7 GPA or finishing an internship.

Research performed published in the Academy of Management journal also suggests that goals are much more likely to be met if the goal is set by the person attaining the goal. Shalley, Christina E. (1995, April). Effects of coaction, expected evaluation, and goal setting on creativity and productivity. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 483–503. For example, if Sherry’s parents want her to become a dental hygienist, but she really wants to become an automotive technician, achieving the goal of dental hygienist may be more difficult, because it’s not her own. While this may seem obvious, we can easily take on goals that other people want us to achieve—even well into our adult life. Expectations from our partner, spouse, friends, and social group can influence our goals and make them not our own. For example, if in your group of friends all have the goal of becoming lawyers, we can assume this should be our goal, too. As a result, we may try to meet this goal but be unsuccessful or unmotivated because it isn’t truly what we want.

Another thing to consider about goal setting is that as we change, and situations change, we need to be flexible with them. For example, let’s say Phil has a goal of earning a degree in marketing. Suppose Phil takes his first marketing class but creates a great idea for a new business he would like to start once he graduates. At this point, Phil may decide earning an entrepreneurship degree instead makes the most sense. It is likely, as a result, since Phil’s goal has changed, objectives and timelines may need to change as well.

Revisiting our goals often is an important part to goal setting. One of the most popular examples for rigidity in goal setting was Ford. In 1969, the goal was to develop a car that weighed less than 2,000 pounds and was less than $2,000. This was to be done by the model year 1971. As you know, this was a very short time to reengineer and redesign everything the organization had done in the past. Ford met their goal, as the Ford Pinto was introduced in 1971.Why Goal Setting can Lead to Disaster. (2012, May 15). Forbes Magazine, accessed May 15, 2012, http://www.forbes.com/2009/02/19/setting-goals-wharton-entrepreneurs-management_wharton.html However, due to the rush to meet the goal, common safety procedures were not followed in the development process, which resulted in disaster. Engineers did not look at the safety issues in placement of the fuel tank, which resulted in fifty-three deaths when the car went up in flames after minor crashes. While this is an extreme example, revisiting goals, including timelines, is also an important part of the goal-setting process.

Time Management

Part of reaching goals also refers to our ability to manage our time. This is also part of emotional intelligence, specifically, self-management—the ability to understand what needs to be done and appropriately allot time to achieve our goals. Time management refers to how well we use the time we are given. In order to meet our goals, we must become proficient at managing time. Common tips include the following:

- Learning how to prioritize. Develop the skills of making sure the most important things are done first (even if they are less fun).

- Avoid multitasking. Focus on one task and finish it before moving on.

- Don’t get distracted—for example, with e-mails, text messages, or other communications—while working. Set time aside to check these things.

- Make to-do lists. These lists can be daily, weekly, or monthly. Organizing in this way will help you keep track of tasks and deadlines. However, note that a study by the Wall Street Journal suggested 30 percent of people spend more time managing their to-do list than actually doing the work on them.30 To-do lists can help manage time but should not be a hindrance to actually getting things done!

- Don’t overwork yourself. Schedule time for breaks and spend time doing things you enjoy.

- Be organized. Make sure your workspace, computer, and home are organized so you can find things easier. Much time is wasted looking for a file on a computer or a specific item you misplaced.

- Understand your work style, a self-awareness skill. Some people work better in the morning, while others work better at night. Schedule important tasks for times when you are at your peak.

- Don’t say yes to everything. Everyone has a limit, and being able to say no is an important part of managing time.

- Find ways to improve concentration. Learning how to meditate for twenty minutes a day or exercising, for example, can help focus your energy.

Effective time management can help us manage stress better but also ensures we can have time to relax, too! Making time management a priority can assist us in meeting our goals. Another important part of career success and personal success is the ability to deal with change, another aspect to emotional intelligence.

Dealing with Change

As we discussed, the ability to set goals is part of emotional intelligence. Perhaps equally as important, being flexible with our goals and understanding that things will change—which can affect the direction of our goals—is part of being emotionally intelligent.

Dealing with change can be difficult. Since most businesses are always in a state of flux, for career success, it is important we learn how to handle change effectively. But first, why do people tend to resist change? There are many reasons why:

- People are afraid the change will affect the value of their skills. For example, if people are afraid of new technology, this could be because they are nervous their skills on the old technology will no longer be useful to the company. To combat this concern, use a can-do attitude about these kinds of changes. Be the first to sign up for training, since we know technological change is a constant.

- People are concerned about financial loss. Many people worry about how the change will affect them from a financial perspective. Will it result in lost hours, lost income? If a change is introduced and you aren’t sure how it will affect these things—and it is not effectively communicated—the best course of action is to talk with your supervisor to clarify how exactly this change will affect you.

- Status quo is easier. People get comfortable. Because of this comfort level, change and the unknown seem scary. Try to always look for new ways to enhance and improve the workplace. For example, revisiting and improving the process for scheduling can help us from becoming stagnant.

- Group norms exist. Sometimes team members are happy to change, but the company does not have a culture that embraces change. Listening to people’s ideas and reacting positively to them can help create a climate of change. Avoiding defensiveness and “going along with the crowd” can help combat this reason for not embracing change.

- Leadership is required. The leadership in our organizations may not provide all of the information we need, or we may not trust them enough to lead us through a change. Despite this, change is inevitable, so obtaining clarification around the change expectations can be an important step to not only understanding the change, but helping the leader become a better leader.

When a change occurs or is occurring, people are likely to experience four phases associated with that change. First, they may experience denial. In this phase, they do not want to accept the change nor do they want to move on to the future. In the resistance phase, people may feel angry or hurt. They may wistfully think about how great things were before the change. In the third phase, exploration, the person may begin to accept the change but with some reservations. In this phase there may be confusion as people start to clarify expectations. In the commitment phase, people have accepted the change, understand how they fit with the change, know how the change will affect them, and begin to embrace it. For example, assume Alan is an expert on the company’s most popular product offering, a special computer program used for accounting purposes. He is the organization’s top seller, with many of his commissions coming from this product. However, the company has just developed new accounting software, which has much better features for customers. He might find this adjustment difficult because he is comfortable with the current software, and it has been lucrative for him to sell it. Here is how he might go through the phases (see Figure 7):

- Denial. Alan does nothing. He continues about his job and ignores e-mails about the new product.

- Resistance. Alan tells his coworkers that the change is unnecessary and wonders why they can’t continue selling the old product. He discusses why the old product is much better than the new one. He may complain to his manager and find reasons why the change is a bad idea.

- Exploration. Alan is still nervous about the change but begins to use the new software and realizes it may have some worthwhile features. He wonders how that affects his ability to sell the product, and he begins to think about how he might sell the new software.

- Commitment. Alan takes some training classes on the new product and realizes how much better it is. He talks with his coworkers about the new product and helps them understand how it works. He sends an e-mail to his customers introducing the new software and all of its benefits.

As you can see in this example, Alan’s resistance to the change was because he didn’t understand the need to change at first and he was worried about how this change would affect the value of his skills.

Because of technology changes and the fact that many companies have global operations and the need for businesses to be agile, change is a constant force affecting business. Be positive about change and accept it as a necessary part of our work life. We cannot expect things to stay the same for very long. The better we can get at accepting change, the more successful we will likely be in our career.

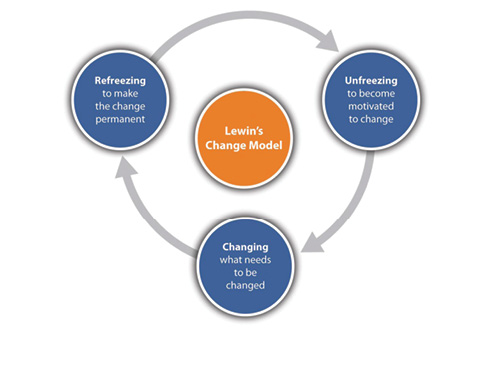

Many a theory has been written about how people undergo change, but one of the more popular models is Lewin’s Model on Change.31 His model proposes three main phases to handling change (Figure 8):

- Unfreezing. Friction causes change and reduction of forces cause a change to happen. For example, suppose Gillian has been unhappy in her job for three years. She recently gets a new manager who she doesn’t like, and a friend tells her about a job at a competing company. In this case, friction occurred (the new manager). In addition, Gillian was worried she wouldn’t be able to find another job, but now that she knows about a new job, that reduces the forces that prevented her from changing to begin with.

- Change. Now that motivations to change have occurred, the change needs to actually occur. Change is a process, not one event at one time. For example, assume Gillian realized taking the new job makes sense, but even though she knows this, accepting the offer and going to her new job on the first day is still scary!

- Refreezing. Once the change has been made, the refreezing process (which can take years or days, depending on the change) is where the change is the new “normal.” People form new relationships and get more comfortable with their routines. Gillian, for example, likely felt odd taking a different way to her new job and didn’t know where to have lunch. Gradually, though, she began to meet people, got used to her new commute, and settled in.

When we become comfortable with change, we are able to allow change into our professional lives. Often, people are too afraid for various reasons to go after that promotion or a new job.

Key Takeaways

Goal setting is a necessary aspect to career success. We must set goals in order to have a map for our life.

When we set goals, we should use the SMART goals format. This asks us to make sure our goals are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-oriented.

When setting goals, we will also use objectives. Objectives are the shorter-term things we must do in order to meet our goals.

Time management is also a factor to goal setting. Developing good time management skills can bring us closer to our goals.

Learning how to deal with change is another way to ensure career success. Many people are adverse to change for a variety of reasons. For example, sometimes it is easier to maintain status quo because we know what to expect. Other reasons may include concern about financial loss and job security, unclear leadership communication, and the existence of group norms.

Besides attitude and behavior, career promotion means being uncomfortable with possible changes. People resist change because of fear of job security, fear of the unknown, fear of failure, their individual personality, and bad past experience with change.

Lewin’s model suggests three phases of change, which include unfreezing, change, and refreezing. These changes indicate that some motivation must occur for the change to happen (unfreeze). Once the change occurs, there can still be discomfort while people get used to the new reality. Finally, in the refreezing part, people are beginning to accept the change as the new normal.

Exercises

- Using the SMART model for setting goals, create at least three long-term goals, along with objectives.

- As you learned in this chapter, time management is an important part of meeting goals. Take this time management quiz to determine how well you currently manage your time: http://psychologytoday.tests.psychtests.com/take_test.php?idRegTest=3208. Do you feel the test results were accurate? Why or why not?