5: History

- Page ID

- 248156

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)1) What is History?

Though you have likely spent a good part of your education sitting in history classes and reading history books, you probably have not really thought deeply about how to define the subject. In many ways, it’s easier to start with what history is not: It is not simply a record of what happened in the past. For one thing, clearly too much happened yesterday alone—let alone ten, one hundred, one thousand years ago—to record. People ate meals, chose which socks to wear, kissed someone new, scanned their Twitter feed, etc., etc.

History is not even a record of important things that happened in the past, because that definition raises the question of what counts as important and who gets to decide. If those new lovers kissing for the first time were Antony and Cleopatra—whose relationship redirected Egyptian history—or if the meal inspired an immigrant activist by reminding of her roots, then those seemingly mundane actions were critical.

Deciding what is important—which among myriad of past events should be retold, the order to put them in, how to phrase stories so that they reach the right audience—that is what history is. As historians James Davidson and Mark Lytle put it, “History is not ‘what happened in the past;’ rather it is the act of selecting, analyzing, and writing about the past.”

Historians are tasked with finding evidence about the past and then deciding what to do with it. They research, evaluate, and write using what past actors have left behind. That means that the historical narratives scholars create actually depend upon scholars’ interpretations of surviving evidence— on what are called “primary sources.” Primary sources are those produced by the people living at the time the events are occurring and can run the gamut from oral histories to government documents to Hollywood films to material culture and beyond.

Historians also keep in mind other historians’ writings, or secondary sources. Historians seek as many sources from as many different perspectives as possible, and scrutinize each one carefully, in the attempt to overcome any biases infusing those sources. We’ll talk more about primary and secondary sources below.

Yet no matter how skilled the researcher there will be gaps in the sources that require interpretation. Gaps or silences in the record merit attention, meaning that historians must consider why some perspectives are not found in archives or in published scholarship. The reason may be perfectly harmless, such as the warehouse fire in 1921 that destroyed the 1890 U.S. Census questionnaires. The resulting silence about literacy rates among immigrants (or a number of other topics that rely on Census records) for that decade is frustrating and has certainly diminished our knowledge of the past, but historians do not need to explain the silence beyond noting this accident of history.

At other times, silences speak directly to the experience of those under study, such as the shortage of written records by enslaved peoples. In this case, the silence must be explained by the pernicious decision by White legislators to limit the literacy of enslaved Americans and is itself a part of the history of slavery.

In sum, historians must be adept at not only ferreting out sources and assessing their meaning, but also evaluating the meaning of what remains hidden. Writing history is at heart the art and science of deciding how to stitch together what remains of the past in a way that is meaningful to readers in the present.

Where does the (social) science part come from? Though gaps in the record mean that we can never know everything about the past–and thus a certain amount of art and interpretation is necessarily a part of history–historians mimic scientific processes, posing and testing hypotheses and placing weight on the use of peer review before publication. Guidelines about the value of a source, rules about how you record where you find it, and advice on how to present your findings when you present them to the public (or just your instructor) are all part of an effort to create reliable scholarship that can be replicated—the key elements of reason. Writing and teaching history successfully depends upon the ability to understand and master those guidelines. While histories know a good deal of art shapes their interpretations, they still value the role of scientific inquiry in their discipline.

The Philosophy of History

Historical interpretations vary over time and between competing points of view. For example, in the past, some historians embraced the notion of cyclical history (that time is not linear, and events reoccur repeatedly) or providential history (that God is directing all events for a particular outcome). More recently, there is also the progressive view (that humanity is constantly improving) and the much more common postmodern view of history (that a pure understanding of the past is unknowable, but that learning as much as we can about the past from our current constantly changing perspectives helps us learn more about ourselves and our own time).

Within the context of the more modern day, history also involves historical debates–discussions in which some historians try to convince others to revise previous interpretations of past people and events for a range of reasons. Some of these debates stem from differences in political perspective, some emerge out of access to new sources or new ideas about how to read old sources. Other conflicts between historians happen because of a difference in approach to how societies work. For example, roughly speaking, some historians emphasize the ability of culture and ideas to shape the importance of economic/material infrastructure, and other historians see it the opposite way around (that is, that certain geographies or other material structures permit or promote what sort of ideas and cultural artifacts develop).

The section below, which explains historiography, will give you some tools for discerning interpretive points of view. Awareness of differences and understanding where they come from are among the most important critical thinking skills of an historian.

Historiography

Writing about the past has changed over time. In other words, history has a history, and the fancy term for how historians recount and analyze previous interpretations of the past is “historiography.” Historiographical change refers to the fact that over time, historians have altered their explanations of past events, and the discipline of history keeps track of, and continuously reconsiders, these changing interpretations. The history of history is called historiography.

One of the easiest ways to grasp the importance of historiography involves looking at a subject such as slavery in the United States. The history of slavery has changed dramatically over the last one hundred years. The first professional historians of slavery wrote in the very years in which state and local governments were establishing and justifying racial segregation. Their interpretations of the “peculiar institution” (as slavery was sometimes called) fit in with their society’s world view, and often suggested slavery was benign or at least a critical part of the process of “improving” those of African descent.

As legal segregation and other types of racialized thinking came increasingly under attack over the course of the twentieth century, such views were criticized and the historians of slavery more often focused on the violence and dehumanizing elements of the institution. As the Civil Rights Movement led to the outlawing of segregated education, it opened the door to new Black and other scholars with new perspectives. Critical race studies today–scholarship that assesses the many ways that the practice and justification of racial slavery still shapes U.S. politics and society and holds that current American society and institutions are not “colorblind” – has a decidedly different view of enslaved peoples than did the history written in the past.

The scholarship about the history of race also actually has within it a variety of perspectives, including differences between historians about how the global economy, technology, religion, gender and/or disability shaped the experience of the enslaved, those who claimed ownership of enslaved people, and those who fought for and against the institution of slavery.

Though other historical topics may not have seen shifts as dramatic as the scholarship on slavery, every subject has experienced some shifting over time. Historians writing articles or books often begin by explaining earlier interpretations in order to show how their own work will add to what we already know, perhaps by pointing out errors in the use of a primary source or how a particular philosophical or political assumption unfairly limited analysis. This is important, because historians who don’t consider current knowledge risk “reinventing the wheel” or worse, creating a faulty interpretation because of unfamiliarity with a major finding by an earlier historian. It is important therefore for historians to know the historiography of topics they are studying.

Linking new understandings to old scholarship is a part of building knowledge. Sometimes the linkage is a direct challenge to past explanations, but more likely new historical writing provides a nuance to the older work. For example, a scholar might look at new evidence to suggest a shift in periodization (“actually the rightward shift in the Republican Party began much earlier than Ronald Reagan’s campaigns”) or the importance of different actors (“middle-class Black women were more critical in the spreading of Progressive reforms in the South than we once thought”). Because historians are concerned with building knowledge and expanding scholarship, they choose their subjects of research with an eye toward adding to what we know, perhaps by developing new perspectives on old sources or by finding new sources.

2) What is Historical Analysis?

History is more than a narrative of the past; the discipline cares less for the who, what, where, and when of an event, instead focusing on how and why certain events unfolded the way they did and what it all means. History is about argument, interpretation, and consequence. To complete quality historical analysis—that is, to “do history right”–one must use appropriate evidence, assess it properly (which involves comprehending how it is related to the situation in question), and then draw appropriate and meaningful conclusions based on that evidence.

Writing history requires making informed judgments; historians must read primary sources correctly, and then decide how to weigh the inevitable conflicts between those sources correctly. Think for a moment about a controversial moment in your own life—a traffic accident perhaps or a rupture between friends. Didn’t the various sources who experienced it—both sides, witnesses, the authorities—report on it differently? But when you recounted the story of what happened to others, you told a seamless story, which—whether you were conscience of it or not—required deciding whose report, or which discrete points from different reports—made the most sense.

Historians use this same judgment when they use primary sources to write history; though in this case there are rules, or at least guidelines, about making those decisions. In order to weigh the value of one source against other sources, we must be as informed as possible about that source’s historical context, the outlook of the source’s creator, and the circumstances of its creation. Each person involved an historical situation brings their own cultural biases and preconceived expectations to that situation, and those biases are integral to the sources they leave behind. It is up to the historian to weave these differences together in their analysis in a way that is meaningful to readers. They must compare differences in ideologies, values, behaviors and traditions, as well as take in a multiplicity of perspectives, to create one story. (This includes the historian knowing what their OWN biases and preconceived notions are as well.)

In addition to knowing how to treat their sources, historians must tell a story worth telling, one that helps us as a society to understand who we are and how we got here, and helps us decide where to go next and how. As humans, we want to know what caused a particular outcome, or perhaps whether a past actor or event is as similar to a present-day actor or event as it seems, or where the beginnings of a current movement began. (“What made Martin Luther King, Jr. a leader, when other activists had failed before him?” “Were reactions to the Civil Rights Movement similar to those of the current Black Lives Matter movement?” “How similar is the Coronavirus pandemic to the 1918 flu pandemic?” “Who were the first feminists and what did they believe?”) Even small aspects of larger events can help answer important questions. (“How did the suffrage movement (or Mothers Against Drunk Drivers, or the gun rights movement, or whatever else) play out in my Texas hometown?”)

The very essence of historical analysis is about analyzing the different cause-and-effect relationships present in each scenario, considering the ways individuals, influential ideas, and different mindsets interact and affect one another. It is about figuring out what facts go together to form a coherent story, one that helps us understand ourselves and each other better. And with that knowledge of what causes tend to lead to what outcomes, we can make more informed decisions about where to go next and how – it can help people with decisions in terms of their personal actions, how to vote, what they will support or won’t, and why, what they believe is that best way to run an economy, etc., all of which help shape the future.

3) How Historians Approach History

Historical Fields

On one hand, history departments throughout the US are dedicated to investigating the totality of the human experience, or at least the past for which we have historical records. But on the other, these departments are also the product of contemporary historical forces. For example, Anglo (white non Latinx generally English speaking people) cultural influence and attention to western culture had a great impact on the history written by Europeans and Americans. In any given department, therefore, you will likely find plenty of faculty specializing in some element of US, European, Western, or Atlantic history.

Political and social movements have impacted how these fields are studied however. Following the Civil Rights movement, newly integrated departments (by race, gender, and sexual orientation) increased attention in scholarship and teaching to “social” histories, or history from below. Histories of laborers, women, people of color, the LGBTQ+ and disabled communities as well as a whole gamut of social movements have caught the interest of historians, and the sub-fields associated with these movements have proliferated.

Of course, most major history departments around the country attempt to also have a faculty member (or sometimes two) from each of the following regional areas: Middle East/North Africa, South Asia, East Asia, Latin American, Sub-Saharan Africa, Australasia. In an increasingly interconnected, globalized world, comparative history has grown in importance and new fields focusing on Atlantic, Pacific, World, transnational, and borderlands history have sometimes supplanted the teaching of history focused on a nation state. With the exception of Atlantic history, which took off during the Cold War and was part of an overarching search for common ground among the allies facing down the Soviet Union, these more expansive fields have become increasingly resonant in the post-Cold War era, which has been characterized by intense globalization and its attendant global labor market, supply chain, and transculturation.

Within these geographic outlines, when pursuing research most historians specialize further in either by approach or time period, or both. Though their teaching subjects can be broader, historians might call themselves experts in the US Civil War, Modern European women’s history, or the cultural and intellectual history of the Ming Dynasty. Apart from the requirements of fluency in other languages, the differences between sources that focus on modern military developments differ quite a bit from those concerning Confucian ideology, and rarely would one historian feel comfortable working with both sorts of primary sources or try to keep track of the historiographical developments in two such divergent fields. As a result, historic sub-fields usually have thematic angles as well, including aspects of technological, economic, political, legal, military, diplomatic, environmental, social, intellectual, or cultural history. The latter fields encompass still more sub-specialties based on gender, sex, race, ethnicity, disability, and legal status. The instructor in your US women’s history class might actually be a specialist on women, gender, race, and sex in the nineteenth-century US South.

Historical Periodization

Another significant way that historians find entry into the vast amount of human experience is to categorize it by blocks of time, or historical periods. At a basic level the names given to historical periods simply provide other options for historical study, in the same way that a historian might specialize geographically or by methodological approach. Fields such as “Nazi Germany” or “Colonial America” both illustrate how political events often define the blocks of time that historians mark for study and do so without controversy.

But more fundamentally, historians’ efforts to identify appropriate historical periods can be very controversial and is at the heart of what they do. Because the point of establishing accepted historical periods is to help facilitate historical analysis, historians hope to identify periods that have stable characteristics.

For example, Victorian England, named after a monarch who ruled from 1837 to 1901, marks a period of rising industrialization, the expansion of British political control around the world, and a transformation and tightening of social rules, especially those concerning women and sex. Scholars of Victorian England suggest that the expansion of empire was in fact related to the increased prudery and expectation of restraint on the part of women. The justification for imperial control rested on ideas of racial superiority, which in turn rested upon an emerging cultural myth about “English ladies” who were ostensibly quite different from newly colonized women of color who had a more casual approach to sex.

But the scholars who identify historical periods are themselves embedded in a specific point in time. Their biases or limited perspective can lead them to over- or under-estimate the importance of an invention, or cultural event, or a popular person of their own era. Indeed, scholars in the late nineteenth century—Victoria’s own contemporaries—started using the label “Victorian England” while she was still alive. Since then, some British historians have questioned the term, arguing that the characteristics we attribute to the period stretch well beyond the limits of her reign. Other historians have defended the term, emphasizing the link between Queen Victoria herself and the many new cultural and social conventions that marked the era—and so the appropriateness of referring to much of the nineteenth century as “Victorian” remains a topic of debate. Likewise, various other blocks of time—the “twentieth century” or the “Renaissance”—regularly inspire discussion about whether they designate a stable period of time or when exactly a period (such as the Renaissance) began and ended.

Another element of periodization is the effort to identify watershed moments. In nature, a watershed is a spot in a river or stream where the lay of the land forces the water to change the direction in which it flows. Watershed events are those occurrences that altered human behavior or ideology in significant ways. For example, the invention and deployment of nuclear weapons changed not only diplomacy and politics in the postwar era, but also many Americans’ sense of security and thus family priorities. Both diplomatic and gender historians see the deployment of atomic bombs in the late 1940s as a watershed moment. Or to take an example from your own lives: Adults living through the current Covid-19 pandemic are already referring to “the Before Times” as a shorthand reference to an earlier historical period, one in which our lives operated differently than they do after the spread of the virus. The lasting changes in technology and the workplace alone indicate the pandemic will be a watershed moment and that “pre-pandemic” and “post-pandemic” will almost certainly periodize the history of public health, work, and education–at a minimum–for future historians.

But like the process of defining historical periods, the identification of historical watersheds leads to a great deal of debate. Is an event identified as a watershed really the moment in which everything changed? Was one person—or their ideas about politics or technology—a “game changer”? Whereas one historian might see the increasingly insularity of 1950s family life as stemming from the fears brought on by the watershed event of the atomic bomb, another might see that development in family life as connected to rising affluence, and suggest that the true watershed moment was not the bomb, but rather the decision of the Truman and Eisenhower administrations to fund research and development for American businesses after the war. Such is the stuff of history and historical debate.

Evaluating Evidence

One of the preeminent guidelines of historical analysis is that all historians evaluate their sources to determine their quality and accuracy. Beyond determining whether a source is primary or secondary, it is imperative that historians use their knowledge to judge the nature of sources and how they should be used. Remember, each primary source carries with it the biases of its author. These biases alter the presentation of information, as many historical sources are written with clear purpose and intention.

Take for example a newspaper editorial written in Atlanta during the American Civil War. Before even reading this document, we need to understand that such an editorial is most likely written from a pro-Confederate source and will therefore be presenting the best possible version of current situation in the war. This source is still very useful for revealing the attitudes of pro-Confederate actors, but information within it about Union troop movements or Union soldiers’ attitudes cannot be accepted as fact. The author’s bias and the historical context of the source’s creation should be noted up front by anyone looking to analyze such a document.

With the understanding of what biases are likely to be present comes the realization that some claims by historical actors may not be entirely true; that is, they are not agreed upon, verifiable from multiple points of view. But again, just because they are not historical facts, they still offer value to those historians seeking to explain opinions and attitudes of a particular place and time.

Evaluating Primary Sources

A primary source is a document/artifact that is "from the time." This means, whatever historical era we are studying, a primary source would have been created/said/written in that time period; the person who wrote/said/created the sources was there and lived through the events in question. For example, a solider writing a letter home during the Civil War, or a girl's diary about traveling west, or a speech given by a president, etc. are all primary sources. Primary sources can also be images or artifacts created at the time, such as paintings, cartoons, pottery, etc.

Questions to ask primary source documents:

Part I- The basics

- Is it authentic (not a fraud)?

- What sort of primary source is it? (newspaper, letter, map, image, government report….)

- Who created the document? As noted above, the "who" is very important as it helps to potentially define the person. For example, a letter written by a Klan member vs. a former slave is exceptionally important information. If we do not identify this, we may take the Klan members' words at face value. The "who" allows us to consider possible bias. (All sources have some bias because they were created by human beings!!!!). Just because someone was there, does not mean they have the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth; what they do have is their perspective and opinion. This does not mean a source from a Klan member, for example, serves no value. It could allow us to see how racism and violence were legitimized and to study how politically violent groups are formed. Thus, even with bias, all primary sources can potentially teach us something.

o When looking at the author, consider what you already know about this person. Having some background allows you deeper insights into their personality, goals, etc.

- About when? A specific date allows us to consider the wider context. For example, a letter written at the start of the Civil War would read very differently than one written at the end, as the author would have new information. Someone recalling an event is still a primary source. For example, if, in 1990, we interview a veteran who fought at the Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945, this would still be a World War II primary source since the person being interviewed was, indeed, there.

- Why (that is, for what audience and purpose)? This helps you do consider the deeper meaning behind their words. Are they trying to convince someone of something, and in doing so exaggerate or romanticize? What is the author’s end game? This must be considered to determine how trustworthy the source is.

Part II – Are you reading the document fairly and/or correctly?

- Remember, the past is a different country. Do you need to know something else (the meaning of words, who someone was, the state of technology, etc.) to understand this document? If so, what?

- Is there any information you can infer or “read between the lines” or interpret based on something NOT said/portrayed? Silences are often important.

Part III – Assessing credibility. Keep in mind that your answers to these questions depend on what information you are claiming for the document.

Was creator of the document in a good place to observe or record the event? If not, why not?

- In what way might the creator have been biased? How might that shape the ‘truth’ of this document? Does the testimony/story seem probable?

- Who preserved the document and why? Can you infer anything from that about preservation? (Not always pertinent, but it’s worth keeping in mind that some voices get privileged over others in the historical record, and we must make allowances for that in our interpretations. Someone might take care to preserve all the personal papers of a politician, but not the diary of their butler.)

- Where might you find corroboration for any interpretive points you find compelling? (That is, you’ll need to solidify support for your argument. What other sorts of primary sources might help do that?)

Questions to ask non-written primary sources:

Primary sources come in all shapes and sizes, which means that the way you go about interpreting them cannot be uniform. Mostly, in non-written sources (including paintings, cartoons, pottery, etc.) you need to be cognizant of visual and aural cues, of placement of subjects in a photograph, of silences in spoken or sung words.

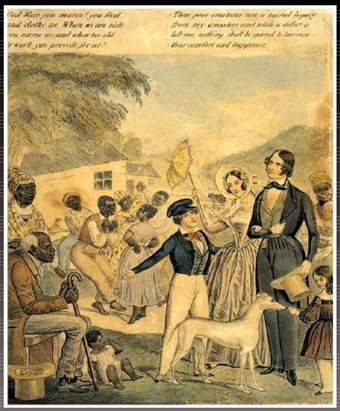

But you also have to know a bit about the technology that shapes the production of those sources. You might think that nineteenth-century Americans were a dour lot, never smiling, if you were not aware of the fact that camera technology in that era enforced rigid stillness, and people were uncomfortable getting caught with a frozen smile. To understand what a map means, you need to know about the conventions of cartography from the society that created it. Artistic creations—paintings or films, for example—often concern historical events and people. But keep in mind, they speak to the values of the artist’s moment, and do not necessarily offer accurate depictions of historical events. (See the American Progress picture above for example. Do you see Native Americans? No. Do you see American soldiers killing all the buffalo? No.)

Here are some basic questions to consider when evaluating a non-written source:

- Who (or what entity) created this source? When and where? What in the political and social milieu would have shaped the circumstances?

- Who was the intended audience?

- How was the source created? What were the technological circumstances? Has it been edited or altered since its original creation? If it is a reproduction, how faithful is it to the original?

- For artistic creations, is it possible to discern the artists’ meaning? Is it possible to discern what critics thought of its meaning?

- Why does the source still exist? Who thought or thinks it important enough to save? Why?

Evaluating Secondary Sources

A secondary source is written/created "about the time." This means someone, ideally an expert in their field (i.e. an historian), is looking backwards in time, studying the past by reviewing primary sources, and then writing a narrative about what happened. This person did not directly experience the events they are writing about. Historians also rely on the works of other scholars' secondary sources/retellings of the past, making them also "tertiary (third) sources."

Secondary sources can also be images such as new maps, charts, recreated paintings, etc.

But again, as with primary sources, not all are equally reliable. Analysis of secondary sources is also a skill people should practice, as this is the place we most often receive news and information. Many of the questions we need to consider when analyzing a primary source are similar for a secondary source.

Questions to ask yourself when reading a secondary source:

- What type of source is this and where is its published? It is an academic book? A magazine article? A personal website?

- These questions help us determine if the source is academic or not. Because the past explains the present, many people look to the past to support their modern-day politics or other personal beliefs potentially twisting history. Determining whether a source is academic or not, opinioned or not, helps us discern how trustworthy its content is.

- Who wrote or created the document?

- Similar to a primary source, knowing who the author may help to determine if they are a trustworthy source. For example, if you are reading a book written by a conservative media host, you may want to consider why they wrote the book and their real purpose in discussing the past. However, even academics hold bias, and it is good to know their prior research and publishing.

- When was the document written/created?

- The date tells us how recent the source was written. If you are reading a history textbook about the Civil War, written in 1950, it is likely the text does not cover new insights or understandings of the Civil War. (But it could be interesting and helpful still in terms of historiography.)

- What was the author/creator's purpose? What was their goal?

- This helps you do consider the deeper meaning behind their words. As with a primary sources, are they trying to convince someone of something?

- What information does the document provide?

- What do you learn from reading/viewing it?

- Who is the audience?

- Who was this made for? Even academics expect a certain audience – other academics, college students, a political group, etc. Consider how words or phrases are adjusted to meet the perceived audience needs.

- What evidence is provided?

- How does the author attempt to support their thesis? What kind of evidence is provided? Read the footnotes and view their citations. Is the evidence strong? What do they cite?

- How does this source fit into the wider scholarship?

- Consider why we should care about this source and why it matters in understanding history. Historians typically write for one of the following reasons:

- The historical issue has not been fully analyzed, thus the author is the first to develop an argument on the topic.

- The historical issue has some gaps in the scholarship.

- The historical issue is commonly interpreted one way. The author seeks to reinterpret the topic or more accurately understand the topic.

- The historical issue is overly simplified. The author seeks to identify complexities or other details.

- The historical issue raises modern-day debates and the author wishes to provide their, or varying, perspectives.

Avoiding Historical Fallacies

Historical fallacies come about due to false reasoning on the part of historians. Their arguments may be built upon shaky logic by not considering the possible biases of their sources or by using incomplete and corrupted evidence. Fallacies can come about by not considering multiple points of view or perspectives in gathering documentary evidence, or from lack of complexity when analyzing causality, or from imposing modern sensibilities upon actors in the past, or from not considering change over time. Presented as rational and well supported conclusions, fallacies are incredibly dangerous as they actively spread misinformation and cover up objective historical arguments. Fallacies can be created both intentionally and unintentionally, depending on their authors, the subject matter, and the influence certain arguments can have.

One powerful example of a historical fallacy is that the American Civil War was fought over the issue of states’ rights. This argument clouds the immense role that slavery played as the primary cause of the war. By arguing that it was simply about states’ rights, one is presenting an overly simplistic and incorrect version of history that is damaging in countless ways.

Fallacy is incredibly dangerous in historical work as an established and believed fallacy can impede the proper and well-constructed historical analysis from being accepted, sometimes for generations. These historical fallacies can be weaponized and used for political purposes while always slowing the progress of solid historical work. If historians are constantly working to undo the entrenchment of fallacy, they are slowed in progressing their fields. A powerful historical fallacy can be used by interested parties to bring about devastating events and have countless times in world history (think for example of Hitler and the Nazi Party, who used historical fallacies to stir up nationalism and support for war in the German public).

In order to avoid historical fallacy, we must be open-minded to proper historical analysis, understand and view multiple perspectives in any event, and focus on determining the difference between facts and biased opinions masquerading as facts. By allowing the historical analysis process to take place in full, we as a society can push dangerous fallacy aside and arrive at objectively determined historical conclusions.

4) The Stakes of Historical Scholarship

Historians spend a lot of time reading historical monographs, analyzing primary sources, learning the narrative of events that led to a war or new invention or a major social shift. Looking at the work of the professional historian might tempt you to think that historians just do history for other historians and so doing bad history will only affect a small group. But that is simply not true.

What people believe about history is foundational to their identities, worldviews, and the collective consciousness of the groups they belong to. People’s worldviews also inform their political opinions and choices. This in turn affects what policies a nation adopts, policies ranging from domestic issues to foreign policy. Getting historical analysis right is, therefore, a very important.

New historical interpretations have helped marginalized groups gain awareness of a past community and a better understanding of their own identity; likewise, good history has aided policymakers in drafting ideas about how they might address social problems. Clearly getting it wrong has an impact as well, leading to misunderstandings, ineffective policies, continuation of inequities, cultural hostilities, etc.

Historical scholarship has had direct impact in this way. In the 2015 SCOTUS decision Obergefell v. Hodges (legalizing marriage equality) the court’s majority decision was written by Justice Anthony Kennedy. He pointed out that social and legal aspects of marriage have changed over time, and to buttress this point he cited briefs submitted by the two most important historical organizations in the U.S.: The American Historical Association and The Organization of American Historians. Additionally, lawmakers and executives at all levels of governance often consult historians when trying to understand specialized topics, or when they are wrestling with how to combat long-standing issues.

Some historians subscribe to the notion that their job is to produce scholarship and then allow it to diffuse to the public via incorporation into textbooks and curricula. However, over the last few years with the explosion of social media, blogs, and podcasts, historians have seized upon the opportunities inherent in these platforms. So while “fake news” stories spread on social media, historians and other academics are busy doing their best to flood newspapers, the Twittersphere, blogs, and the airwaves/podwaves with expert opinions.

Many historians have used Twitter to try to educate or correct popular misconceptions. Efforts by historians have been crucial to correcting the media and helping to foster informed debate. In 2019, one popular historian went on NPR’s morning show to say that in her research she found no evidence that women used contraception or abortion services in the nineteenth century, and Lauren MacIvor Thompson, a specialist in female reproductive rights, responded with a Twitter thread and several links to point out how laws, such as the Comstock Law of 1873, made it impossible for women to speak forthrightly about these issues so euphemisms had to be employed. MacIvor Thompson’s thread went viral and NPR quickly posted a correction. MacIvor Thompson’s expertise was quickly recognized, and she was then asked for an interview by The Atlantic for a piece on suffragists and the birth control issue.

Why Historical Methods Are Important

History is in fact everywhere, because everything has a history. But not all history-based productions are equal. Professional scholars are not the only ones who like to claim the mantle of “historian.” Amateur historians, journalists, politicians, political pundits, and filmmakers also publish/produce works of history of varying sophistication. But they are not always to be trusted. History has rules and good history follows those rules. History that doesn’t is often not reliable history.

A key feature of academia is that anything academics publish must adhere to shared standards of scholarship through a process known as peer-review—which is sort of like grading by other professors. Before a scholar can publish a journal article or monograph with an academic press (or trade presses with similar standards), they submit a draft for review. In this process, the editor of the press or journal contacts other historians who specialize in the same field and asks them to read the essay to make sure that the analysis follows the standards for scholarship and if it makes a worthwhile contribution to the field. Academic presses are committed to these standards, and cannot publish material they know violates it, even if they thought the subject was interesting or profitable. “How many books will it sell?” is not a standard for good history.

Rather than wondering simply “Will people buy this book?” academic presses ask a different set of questions: Is the argument clear and supported by verifiable facts in evidence? Are the sources appropriate and sufficient to support the author’s analysis? Has the author avoided faults in logic and plagiarizing other scholars? Does the essay address (and effectively counter) any interpretations that conflict with the one presented? If the peer reviewers believe the essay does not meet these standards, it is returned to the author for revision. Sometimes even if peer reviewers recommend publication, they will ask for improvements. One important result of the peer review process is better written, better explained, better supported essays.

Better written does not necessarily mean more accepted of course, because historians will always find something to debate. But the common ground created by the peer review process means that those debates usually result in some come consensus about what we know. Though contemporary historians generally acknowledge that knowledge about the past is partial and that individual perspectives may bias interpretations, most do believe that we can approach the “truth.”

Above all, scholarship is not opinion. The peer-review process ensures that only the results of fact-based inquiry get published. Historians’ respect for fact-based, logical arguments that do not leave out key pieces of evidence mean that they can trust the premise and argue about the interpretation itself—whether other sources might yield a different conclusion, or if a revised assessment of an individual’s actions is as well-supported as the previous one. The ensuing debates—and historians do love to debate—are key to the development of what we agree upon as historical facts and likely explanations for how and why events happened as they did.

As new research is presented in the form of conference presentations, essays, and books, historians inevitably argue about differing interpretations, leading to a fine-tuning of our understanding of the past. Over time a synthesis develops, as well-supported, convincing explanations emerge, and historians agree on about the causes and impact of a particular event (until the next, more convincing interpretations gets published!).

SOURCES

OER Commons [oercommons.s3.amazonaws.com]

Open UMN [oercommons.org]

OER Commons [open.umn.edu]