14: The Issue of Crime

- Page ID

- 248165

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)What is crime?

Before we can measure crime, understand its causes, or think about policy solutions to prevent and reduce crime, it is important to take a step back and ask a fundamental question: What is crime? In the simplest terms, a crime is an illegal act or action. That however only takes us so far. What is made illegal and is therefore considered a crime varies over time and space. There are numerous examples of actions that were once illegal that are now not widely considered to be crimes. For example, various laws have been created and nullified against homosexuality, bullying, and drug use depending on public perception. There are crimes in some countries that are not considered crimes in others. So to ask what crime is depends on who is defining crime and how that decision is being made. In the United States, laws are typically passed by local, state, and federal legislatures by elected representatives. Thus, the attitudes, including the biases, of voters and policymakers may become embedded in the law.

The Social Construction of Crime

The social construction of crime refers to the idea that crime is not an objective concept. Instead, society, through its institutions, norms, values, and laws, constructs the definition of what is considered criminal behavior, how that the behavior will be viewed, and how severe the punishment will be for it.

For example, the laws and punishments for different forms of cocaine. Crack cocaine is produced from powder cocaine, but the amount of crack cocaine that triggered eligibility for a mandatory minimum sentence was 1/100th the amount of powder cocaine. This disparity embodied racial biases, as the majority of individuals (more than 80%) of those convicted for crack cocaine offenses were African American, compared to a third of those convicted for powder cocaine and other drugs. In response to outcry around the bias in sentencing, this ratio was changed to set a minimum sentence for crack cocaine at 1/20th the amount of powder cocaine. However, the law still embodies biases that disproportionately harm African-American communities. (Bjerk 2016; Vagins and McCurdy 2006)

As another example, people understand property theft clearly as a crime, as when an employee steals goods from an employer, or a customer shoplifts. But what is less well known and less seen as a crime is wage theft. Wage theft can come in many forms: paying less than minimum wage, not paying overtime, not granting sick leave, not giving tips to workers who are supposed to receive them, asking for “off the clock” work before or after a shift begins, denying meal breaks, taking illegal deductions from checks, or misclassifying workers as independent contractors to avoid paying minimum wage or overtime. Wage theft is worth billions of dollars to employers, yet people are much less likely to know about it, talk about it, or hear about it in the news or other media, especially as it mostly impacts low-wage workers, immigrants, minorities, and women. Wage theft is not constructed as a crime in the way other property theft is.

Society generally socializes its members to view certain crimes as more severe than others. For example, when people think of violent and non-violent crime, they often picture street crime, or offenses committed by ordinary people against other people or organizations, usually in public spaces (for example, mugging as violent crime or car theft as non-violent crime). An often overlooked category of both violent and non-violent crime however is corporate crime. There is nonviolent corporate crime (or “suite crime”), crime committed by white-collar workers in a business environment. Embezzlement, insider trading, Ponzi schemes, false advertising, price-fixing and fraud are all types of corporate crime. Although these types of offences rarely receive the same amount of media coverage as street crimes, they can be far more damaging. The 2008 world economic recession was the ultimate result of a financial collapse triggered by corporate crime.

There is also corporate violence, actions by corporations that kill or maim people or leave them ill. The victims of corporate violence include corporate employees, consumers of corporate goods, and the public as a whole. These involve unsafe work places, which cause illness and death, and unsafe products that kill or maim consumers. The toll of white-collar crime dwarfs the toll of street crime, even though the latter worries us much more than white-collar crime. Despite the harm that white-collar crime causes, the typical corporate criminal receives much more lenient punishment, if any, than the typical street criminal (Rosoff et al., 2010).

The media can play into this. One reason is that violent crime lends itself to spectacular media coverage that distorts its actual threat to the public. Television news broadcasts frequently begin with chaos news — crime, accidents, natural disasters — that present an image of society as a dangerous and unpredictable place. However, the image of crime presented in the headlines does not accurately represent the types of crime that actually occur. The issue is that the news is a commercial product used to sell newspapers and advertising. “If it bleeds, it leads” is the adage that describes the financial motivation to publish the most dramatic crime news because it sells more subscriptions and receives more views. Czerny and Swift (1988) argue that the commercial media distort the content of the news in a number of ways. Typically stories emphasize:

- the intense (stories are selected to play up drama and action)

- the unambiguous (complex issues and lived experiences are simplified into straightforward moral stories of good and bad)

- the familiar (stories are made to fit in with common sense understandings and prejudices)

- the marketable (stories are packaged to appeal to consumer tastes, often with sex and violence imagery)

This distortion is amplified by the use of on-line sources where many people get their news most of the time. Emotional responses to stories rather than critical analysis influence people’s decisions to “retweet” a story (Stieglitz & Dang–Xuan, 2013). Emotions have also been shown to be contagious in on-line environments and are linked to rumor spreading behavior (Kramer et al., 2014; Oh et al. 2013; Pröllochs et al., 2021). Vosoughi et al.’s (2018) research showed that on social media platforms like Twitter “falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.”

The media tends to highlight crimes committed by African Americans or other people of color and crimes with white victims. A greater percentage of crime stories involve people of color as offenders than is true in arrest statistics. A greater percentage of crime stories also involve whites as victims than is actually true, and newspaper stories of white-victim crimes are longer than those of black-victim crimes. Crimes in which African Americans are the offenders and whites are the victims also receive disproportionate media coverage even though most crimes involve offenders and victims of the same race. In all these ways, the news media exaggerate the extent to which people of color commit crimes and the extent to which whites are victims of crimes.

Why Does Crime Occur?

Explanations rooted in the individual biology or psychology of criminal offenders do not stand up as explanations of crime. While a few offenders may suffer from biological defects or psychological problems that lead them to commit crime, most do not. Further, biological and psychological explanations cannot adequately explain why higher crime rates are associated with certain locations and social backgrounds. For example, if California has a higher crime rate than Maine, and the United States has a higher crime rate than Canada, it would sound silly to say that Californians and Americans have more biological and psychological problems than Mainers and Canadians, respectively. Biological and psychological explanations also cannot easily explain why crime rates rise and fall, nor do they lend themselves to practical solutions for reducing crime.

In contrast, sociological explanations do help understand the social patterning of crime and changes in crime rates, and they also lend themselves to possible solutions for reducing crime. Sociologists have developed theories attempting to explain what causes deviance and crime and what they mean to society. These theories can be grouped into three areas: positivism, critical sociology and interpretive sociology.

Positivist types of theory focus on identifying the background variables in an offender’s social environment that determine or predict criminal and deviant behavior. In this view, both crime and environmental factors are easy to define. Crime is simply rule-breaking or law-breaking acts. How or why those acts became to be considered criminal is not considered. The environmental factors that affect a person’s likelihood to commit crime are also seen as straightforward in this view - positivism focuses on identifying factors that are directly observable or measurable.

In positivism, the reason why a person commits crime is not usually individual defects (a person commits crime because they are “just degenerate”) but rather the reason is “social defects” – something is wrong in their social environment. Crime is not the result of a defective human being but a defective social environment, and the factors that make a defective social environment are considered to be observable and measurable facts. Going into all of the ways the social environment can be defective and encourage crime is beyond the scope of this chapter. The key understanding here is that in this view, crime is largely result of social factors, not individual ones, and both crime and social factors are considered relatively easy to define and observe.

Another view is critical sociology. Critical sociology examines structural inequalities based on class, gender , race, other power relations in society to explain crime and deviance. This view takes into consideration what crime is and the meaning of crime. Why are certain acts punished as criminal or deviant and certain acts not? Why are certain types of crime or deviance prevalent in one community, gender or social strata and not in others?

Like positivists, critical sociologists examine social and economic factors as the causes of crime and deviance. Unlike positivists, however, critical sociologists do not see these factors as objective social facts, but as evidence of operations of power and entrenched social inequalities. What is seen as crime and the criminal justice system are not simply neutral mechanisms designed to further the best societal order. Law and the criminal justice system are mechanisms that actively maintain a particular political and economic power structure that favors some over others.

The rich, the powerful, and the privileged have unequal influence on who and what gets labelled deviant or criminal behavior, particularly in instances where it is their privilege or interests that are being challenged by that behavior. As capitalist society is based on the institution of private property, for example, it is not surprising that theft is a major category of crime, and theft from business is more focused on than theft by business. By the same token, when street people, addicts, or hippies drop out of society, they are labelled deviant and are subject to police harassment because they have refused to participate in the productive labor that is the basis of capital accumulation and profit.

Richard Quinney (1977) examined the role of law, policing and punishment in modern society. He argued that, as a result of inequality, many crimes can be understood as crimes of accommodation, or ways in which individuals cope with conditions of inequality and oppression. Predatory crimes like break and enter, robbery, and drug dealing are often simply economic survival strategies. Defensive crimes like economic sabotage, illegal strikes, civil disobedience, and eco-terrorism are direct political challenges to social injustice.

On the other hand, crimes committed by people in power are often crimes of domination. Crimes of control are committed by police and law enforcement, such as violations of rights, over-policing minority communities, illegal surveillance and use of excessive force. Crimes of government are committed by elected and appointed officials of the state through misuse of state powers, including corruption, misallocation of funds, political assassinations and illegal wars. Crimes of economic domination comprise white collar and corporate crime, including embezzlement, fraud, price-fixing, insider trading, tax evasion, unsafe work conditions, wage theft, pollution, and marketing of hazardous products. Crimes of social injury include practices of institutional racism and economic exploitation, violations of basic human rights, or denials of gender, sexual and racial equality, that are often not considered unlawful.

Those in power define what crime is and who is excluded from full participation in society as a matter of course. Quinney pointed out that crimes of domination are not criminalized and policed to the degree that crimes of accommodation are, even though the harms they pose to society are greater and affect more people.

This perspective also plays out in gender, especially in a patriarchal society where men have the most power. Women who are regarded as criminally deviant are often seen as being doubly deviant. They have broken the law but they have also broken gender norms about appropriate female behavior, whereas men’s criminal behavior is seen as consistent with their aggressive, self-assertive character. This double standard explains the tendency to medicalize women’s deviance, to see it as the product of physiological or psychiatric pathology. In other words, women are more likely to be seen as having committed crimes because they are experiencing individual mental or psychological issues, and not because of any broader social or political or economic reality.

Feminist analysis focuses on the way gender inequality influences the opportunities to commit crime and the definition, detection, and prosecution of crime. Why is abortion no longer a Constitutional right in the US and thus a crime in many states? This reflects the gendered nature of the “crime” (only people with a uterus have abortions) and the attitudes of those in power that have made it a crime. Why, on the other hand, is the crime of rape still so difficult for women to report and prosecute? Why is domestic violence still considered to be a “private” problem? Again, because of the gendered notions of these crimes and the people in power who control the legal mechanisms that surround them.

Finally, interpretive sociology focus on how the meanings of criminality or deviance get established. Key to understanding crime and deviance is not simply the objective fact of law-breaking or rule-breaking, but the process whereby that happens and what the act of law breaking means to the person doing it.

For example, having a social milieu in which most of one’s contacts encourage or normalize criminality predicts the likelihood of becoming criminal, whereas a social milieu where one’s contacts discourage criminality predict the opposite. A teenager whose friends shoplift is more likely to view shoplifting as acceptable or even desirable to remain within the norms of that circle of friends.

Procurement into prostitution involves a similar process, one which is manipulated by the procurers or pimps. Hodgson (1997) describes two methods of procurement that pimps use to draw girls into a life of prostitution. After judging a girl’s level of vulnerability, they deploy either a seduction method, providing affection, attention and emotional support for the most isolated girls, or a stratagem method, promising wealth, glamour and excitement for those who are less vulnerable. After a girl has “chosen” to stay with the “family,” they are socialized step by step to comply to the roles, rules and expectations of the world of prostitution. Their former identity is neutralized and attachment to previously learned values and norms is weakened through a process that begins with (a) training in the rules of the sex trade by the pimp’s “wife-in-law” or “main lady,” (b) turning the first trick, which deepens the girl’s identification with street culture and the other prostitutes, and (c) the use of violence to enforce compliance when the girl has second thoughts and the relationship with the pimp deteriorates.

At each stage the girl finds herself more deeply entrenched in a world of norms, values and behaviors that are strongly stigmatized in the dominant culture. While various levels of coercion are also present, the process of learning, internalizing and acknowledging the deviant self-image and social role of the prostitute is necessary for continued participation in prostitution.

Here also we see the phenomenon of labeling, whereby people gradually come to believe they are deviant because they been labelled “deviant” by society. A person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after their actions are labelled as deviant by members of society. The person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labelled that individual as such. For example, consider a high school student who often cuts class and gets into fights. The student is reprimanded frequently by teachers and school staff, and soon enough, develops a reputation as a “troublemaker.” As a result, the student might take these reprimands as a mark of status and start acting out even more, breaking more rules, adopting the troublemaker label and embracing this deviant identity.

The criminal justice system is ironically one of the primary agencies of socialization into the criminal “career path.” The labels “juvenile delinquent” or “criminal” are not automatically applied to individuals who break the law. A teenager who is picked up by the police for a minor misdemeanor might be labelled as a “good kid” who made a mistake and who then is released after a stern talking to, or they might be labelled a juvenile delinquent and processed as a young offender. In the first case, the incident may not make any impression on the teenager’s personality or on the way others react to them. In the second case, being labelled a juvenile delinquent sets up a set of responses to the teenager by police and authorities that lead to criminal charges, more severe penalties, and a process of socialization into the criminal identity. Which of the two scenarios happens is influenced by the teenager’s race, class, and gender.

Once a label is applied it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Self-fulfilling prophecies refer to the mechanisms put in play by the act of labeling, which tend to shape the person into what the label says they are. A person may or may not initially fit the label given, but through a series of processes eventually does.

The Criminal Justice System

The criminal justice system typically has three main parts: (1) the police, who identify and apprehend those considered to be criminals, (2) the courts, who decide the guilt or innocence of those accused of crimes and sentence them, and (3) corrections institutions, such as prisons, that carry out the penalty determined by the courts.

Police are a civil force in charge of enforcing laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level. No unified national police force exists in the United States, although there are federal law enforcement officers. Once a crime has been committed and a violator has been identified by the police, the case goes to court. A court is a system that has the authority to make decisions based on law. The U.S. judicial system is divided into federal courts and state courts. The corrections system is charged with supervising individuals who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offense, plus people detained while awaiting hearings, trials, or other procedures.

The criminal justice system in a democracy like the United States faces two major tasks: (1) keeping the public safe by apprehending criminals and, ideally, reducing crime; and (2) doing so while protecting individual freedom from the abuse of power by law enforcement agents and other government officials. Having a criminal justice system that protects individual rights and liberties is a key feature that distinguishes a democracy from a dictatorship.

Policing and Race

People of color, Black, and Latinx Americans along with Indigenous people, are disproportionately surveilled and killed by the police. Between 1980 and 2018, police killed an estimated 30,800 people. Black and Latinx Americans were significantly more likely to be killed than White Americans (Sharara et al. 2021). Public opinion studies from the Pew Research Center show that Black Americans are more likely to report having been stopped unfairly by police. It is obvious that Black Americans have very different interactions with police than White Americans, which is reflected in their differences in opinion about the police. They are also less likely to have a positive view of how officers treat different racial and ethnic groups, and they see fatal police shootings as signs of broader issues with the criminal justice system (Desilver, Lipka, and Fahmy 2020).

What is causing the disproportionate impact? There are a few factors that contribute to these trends. The first explanation for racial disparities in policing is the role of spatial profiling. Compared to low-crime, middle and upper-class neighborhoods, high-crime, low-income neighborhoods are more heavily surveilled by the police. It is in these neighborhoods that Black and Latinx Americans are more likely to live, exposing them to more significant contact with the police.

Police training may also play a significant role. For example, only a few training hours are dedicated to topics such as ethics, de-escalation tactics, and providing social services. Instead, using firearms, defensive tactics, and police procedures comprise most of the training. Consequently, it is not surprising that police are more adept at using their weapons when a situation escalates rather than turning to nonviolent options.

The next explanation is bias—both explicit and implicit. (Explicit bias refers to the biased attitudes people know they hold, whereas implicit bias refers to the biased attitudes people hold but might not be consciously aware of and may actually contradict their stated beliefs.) Explicit bias is still an issue with at least some proportion of law enforcement officers. A recent study analyzing 40 years of General Social Survey data has shown that police, unlike most Americans, believe that they should receive more funding and have the right to use physical force against citizens (Roscigno and Preito-Hodge 2021). They also found that White male officers were, in particular, more racist than the general population or those in similar occupations (Roscigno and Preito-Hodge 2021). Implicit bias is also an issue among law enforcement, as it is in the broader American population. Studies have found that implicit bias plays a role in decisions about whether officers will use deadly force (Fridell and Lim 2016).

Racism and discrimination have a direct role in creating explicit and implicit biases, which is evident when looking at the history of the institution of policing. Historically, in both the North and the South, police have been used as a tool of social control to manage “unruly” populations. In the North, police intended to control the growing poor European immigrant population and quell labor protests. In the South, the earliest manifestations of police were slave patrols. While these institutions became more bureaucratic over time and looked more like northern police agencies, they still enforced Jim Crow laws and were not afraid to beat and arrest anyone who dared protest these racially discriminatory laws and practices. Given this history, it is not surprising that there is distrust between Black communities and police departments.

Courts

In the US legal system, suspects and defendants enjoy certain rights and protections guaranteed by the Constitution and Bill of Rights and provided in various Supreme Court rulings since these documents were written some 220 years ago. Although these rights and protections do exist and again help distinguish our democratic government from authoritarian regimes, in reality the criminal courts often fail to achieve the high standards by which they should be judged.

A basic problem is the lack of adequate counsel for the poor. Wealthy defendants can afford the best attorneys and get what they pay for: excellent legal defense. An oft-cited example here is O. J. Simpson, the former football star and television and film celebrity who was arrested and tried during the mid-1990s for allegedly killing his ex-wife and one of her friends (Barkan, 1996). Simpson hired a “dream team” of nationally famous attorneys and other experts, including private investigators, to defend him at an eventual cost of some $10 million. A jury acquitted him, but a poor defendant in similar circumstances almost undoubtedly would have been found guilty and perhaps received a death sentence.

Although poor defendants enjoy the right to free legal counsel, in practice they receive ineffective counsel or virtually no counsel at all. The poor are defended by public defenders or by court-appointed private counsel, and either type of attorney simply has far too many cases in any time period to handle adequately. Many poor defendants see their attorneys for the first time just moments before a hearing before the judge. Because of their heavy caseloads, the defense attorneys do not have the time to consider the complexities of any one case, and most defendants end up pleading guilty.

Another problem is plea bargaining, in which a defendant agrees to plead guilty, usually in return for a reduced sentence. Under our system of justice, criminal defendants are entitled to a trial by jury if they want one. In reality, however, most defendants plead guilty, and criminal trials are very rare: Fewer than 3 percent of felony cases go to trial. Prosecutors favor plea bargains because they help ensure convictions while saving the time and expense of jury trials, while defendants favor plea bargains because they help ensure a lower sentence than they might receive if they exercised their right to have a jury trial and then were found guilty. However, this practice in effect means that defendants are punished if they do exercise their right to have a trial. Critics of this aspect say that defendants are being coerced into pleading guilty even when they have a good chance of winning a not guilty verdict if their case went to trial (Oppel, 2011).

A final problem is the system of bail. If a person is arrested, wrongfully or not, they are in almost all justifications required to pay bail to leave jail and return home to fight the charges. The original idea behind this was to make sure that people returned to court to face the charged against them. However, this system now perpetuates widespread wealth-based incarceration. Poorer Americans and people of color often can't afford bail, leaving them incarcerated in jail sometimes for months or even years while they await trial, losing their jobs and unable to care for their families. Meanwhile, wealthy people accused of the same crime can pay the bail, obtain their freedom, and return home. This practice may be considered unconstitutional, because it violates the rights to due process and equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment, the prohibition against excessive bail found in the Eighth Amendment, and the right to a speedy trial guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment. These practices do, however, make money for the for-profit bail bond companies and the insurance companies who back them.

The Death Penalty

The death penalty is perhaps the most controversial issue in the criminal justice system today. The United States is the only Western democracy that sentences common criminals to death, as other democracies decided decades ago that civilized nations should not execute anyone, even if the person took a human life. About half of Americans in national surveys favor the death penalty (Death Penalty Information Center, 2025).

First, capital punishment does not deter homicide: Almost all studies on this issue fail to find a deterrent effect. An important reason for this stems from the nature of homicide. As discussed earlier, it is a relatively spontaneous, emotional crime. Most people who murder do not sit down beforehand to calculate their chances of being arrested, convicted, and executed. Instead they lash out. Premeditated murders do exist, but the people who commit them do not think they will get caught and so, once again, are not deterred by the potential for execution.

Second, the death penalty is racially discriminatory. While some studies find that African Americans are more likely than whites who commit similar homicides to receive the death penalty, the clearest evidence for racial discrimination involves the race of the victim: Homicides with white victims are more likely than those with African American victims to result in a death sentence (Paternoster & Brame, 2008; also see Death Penalty Information Center, 2025). Although this difference is not intended, it suggests that the criminal justice system values white lives more than African American lives.

Third, many people have been mistakenly convicted of capital offenses, raising the possibility of wrongful executions. Sometimes defendants are convicted out of honest errors, and sometimes they are convicted because the police and/or prosecution fabricated evidence or engaged in other legal misconduct. Whatever their source, wrongful convictions of capital offenses raise the ugly possibility that a defendant will be executed even though they were actually innocent of any capital crime. In March 2011, Illinois abolished capital punishment, partly because of concern over the possibility of wrongful executions. As the Illinois governor summarized his reasons for signing the legislative bill to abolish the death penalty, “Since our experience has shown that there is no way to design a perfect death penalty system, free from the numerous flaws that can lead to wrongful convictions or discriminatory treatment, I have concluded that the proper course of action is to abolish it” (Schwartz & Fitzsimmons, 2011:A18).

Fourth, executions are expensive. In 2020, keeping a murderer in prison for life cost about $1 million dollars (say 40 years at $25,000 per year), while the average death sentence costs the state about $2 million to $3 million in legal expenses. Capital trials (in which the defendant, if found guilty, would face the death penalty) are also much more expensive than non-capital trials. (Death Penalty Information Center, 2025).

This diverse body of evidence leads most criminologists to oppose the death penalty. In 1989, the American Society of Criminology adopted this official policy position on capital punishment: “Be it resolved that because social science research has demonstrated the death penalty to be racist in application and social science research has found no consistent evidence of crime deterrence through execution, The American Society of Criminology publicly condemns this form of punishment, and urges its members to use their professional skills in legislatures and courts to seek a speedy abolition of this form of punishment.” https://asc41.org/about-asc/policy-page/

Correctional Institutions

Costs – and Benefits?

According to the ACLU, incarceration costs the nation at least $80 billion annually. (https://www.aclu.org/issues/smart-justice/mass-incarceration). What does the expenditure of this huge sum accomplish? It would be reassuring to know that the high US incarceration rate keeps the nation safe and even helps reduce the crime rate, and it is certainly true that the crime rate would be much higher if we had no prisons at all. However, many criminologists think the surge in imprisonment during the last few decades has not helped reduce the crime rate at all or at least in a cost-efficient manner (Durlauf & Nagin, 2011). Greater crime declines would be produced, many criminologists say, if equivalent funds were instead spent on crime prevention programs instead of on incarceration (Welsh & Farrington, 2007).

Criminologists also worry that prison may be a breeding ground for crime because rehabilitation programs such as vocational training and drug and alcohol counseling are lacking and because prison conditions are substandard. They note that more than 700,000 inmates are released from prison every year and come back into their communities ill equipped to resume a normal life. Once free they face a lack of job opportunities (how many employers want to hire an ex-con?) and a lack of friendships with law-abiding individuals, as our earlier discussion of labeling theory indicated. Partly for these reasons, imprisonment ironically may increase the likelihood of future offending (Durlauf & Nagin, 2011).

Living conditions behind bars merit further discussion. A common belief of Americans is that many prisons and jails are like country clubs, with exercise rooms and expensive video and audio equipment abounding. However, this belief is a myth. Although some minimum-security federal prisons may have clean, adequate facilities, state prisons and local jails are typically squalid places. As one critique summarized the situation, “Behind the walls, prisoners are likely to find cramped living conditions, poor ventilation, poor plumbing, substandard heating and cooling, unsanitary conditions, limited private possessions, restricted visitation rights, constant noise, and a complete lack of privacy” (Kappeler & Potter, 2005, p. 293).

Some Americans probably feel that criminals deserve to live amid overcrowding and squalid living conditions, while many Americans are probably at least not very bothered by this situation. But this situation increases the odds that inmates will leave prison and jail as more of a threat to public safety than when they were first incarcerated. Treating inmates humanely would be an important step toward successful reentry into mainstream society.

Mass Incarceration

Mass incarceration refers to the overwhelming size and scale of the U.S. prison population.

Some of this dramatic increase was due to the public portrayal of crack cocaine as a highly addictive drug sweeping its way through America. Politicians capitalized on the resulting hysteria and passed policies that rapidly increased the prison population. Even so, the vast majority of arrests and enforcement were not of high-level, violent dealers but, more often, small-time dealers or people struggling with addiction. In fact, during the 1990s, the period of the largest increase in the U.S. prison population, the vast majority of prison growth came from cannabis arrests (King and Mauer 2005).

The 1980s and 1990s were also an era during which states turned to partnerships with private companies to meet the booming demand for facilities, leading to the rise of private prisons. Private prisons are for-profit incarceration facilities run by private companies that contract with local, state, and federal governments. The business model of private prisons incentivizes them to keep their prisons as full as possible, while spending as little as possible on care for inmates. Down 16 percent from its peak in 2012, private prisons still held 8 percent of all people incarcerated at the state and federal level as of 2019 (The Sentencing Project 2021). Still, it is essential to note that the use of these facilities varies by local context. For instance, Oregon has no private prison facilities in the state, while Texas has the highest number of people incarcerated in private prisons.

From the inception of the war on drugs, racial biases were at the center of these policy changes. For instance, John Erlichman, one of Richard Nixon’s top advisors, explicitly admitted to this in a 2016 interview:

“You want to know what this [war on drugs] was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with cannabis and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” (Baum 2016)

Even as the racial gap in incarceration has narrowed in recent years, the United States disproportionately incarcerates Black Americans. While Black Americans make up 13 percent of the population, they make up over 30 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). Similar trends exist among Latinx Americans: while Latinx people comprise 16 percent of the U.S. population, they account for over 20 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). In contrast, while White Americans comprise 64 percent of the population, they only make up 30 percent of those incarcerated (Gramlich 2019).

This network of policies and unequal institutional practices led to what scholar Michelle Alexander terms the New Jim Crow. The New Jim Crow refers to the network of laws and practices that disproportionately funnel Black Americans into the criminal justice system, stripping them of their constitutional rights as a punishment for their offenses in the same way that Jim Crow laws did in previous eras. Because of these new mass incarceration policies, a new iteration of the racial caste system has emerged: one in which Black Americans can legally be denied public benefits, housing, the right to vote, and participation on juries because of a criminal conviction.

The detention of immigrants also intersects with the system of mass incarceration. Recently, attention has been brought to how immigration law and criminal law have been combined in the form of “crimmigration” (Hernandez 2022). The combination of these laws has had a detrimental effect on immigrants. The same companies that run private prisons also play a role in running immigrant detention centers. To learn more about this, you can watch the video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UttL8utsvLA&t=1s

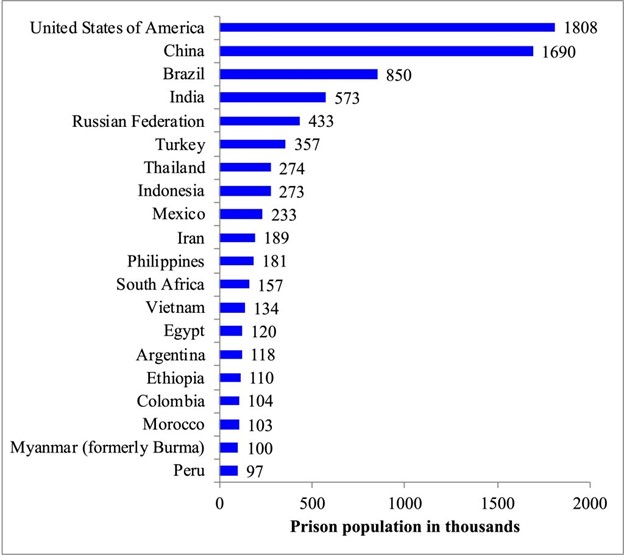

The table above demonstrates the degree to which countries use imprisonment as a form of criminal justice. The United States has by far the largest number of individuals imprisoned, 1.8 million (as of 2022). It is important to note that the United States also has a large population, but even in terms of the rate of imprisonment (prisoners per thousand individuals), the United States has one of the highest rate of imprisonment of any major nation (Institute for Criminal Policy Research 2024).

While racial disparities are one of the most pressing and continuing concerns in the criminal justice system, other marginalized groups face similar institutional inequalities. Recently, there has been an rise in incarceration rates of women and folks who identify as part of the LGBTQIA+ community. Between 1980 and 2019, the number of incarcerated women increased by more than 700 percent (The Sentencing Project 2022). Furthermore, while the United States incarcerates more men than women, the rate of growth of women’s incarceration has been twice as high as that of men since 1980 (The Sentencing Project 2022).

This increase in women’s incarceration is also directly connected to the disproportionate involvement of the LGBTQIA+ population in the criminal justice system. As of 2019, gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals were over two times as likely to be arrested in the past 12 months than straight individuals (Jones 2021). This disparity particularly impacts lesbian and bisexual women, who are four times as likely to be arrested as straight women (Jones 2021). The high rates of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people behind bars can, in part, be attributed to the longer sentences courts impose on them (Meyer et al. 2017). Transgender individuals also report high arrest and incarceration rates and uncomfortable encounters with the police, with one in six transgender individuals having spent time incarcerated (Grant et al. 2011).

Individuals marginalized as a result of their sexual or gender identity may also face issues when incarcerated. These groups are more likely to be sexually victimized while incarcerated, placed into solitary confinement, and report current psychological distress (Meyer et al. 2017). Similarly, transgender and gender nonconforming individuals lack the same civil rights protections as other groups, which leads to poor treatment in incarceration facilities. For instance, President Trump revoked Obama-era federal guidance, which stated that people who are transgender and incarcerated should be held in facilities matching their gender identity and have access to gender-affirming healthcare services. Then, when President Biden took office, he again instituted the Obama-era guidance. When Trump was re-elected, he sent out an executive order denying the existence of trans people altogether, thus the possibility of treatment according to their gender. This reversal from administration to administration is just one example of how contested federal and state political issues directly impact the lives of individuals.

Finally, the criminal justice system has significant problems with how it addresses mental health issues. In terms of policing, people with mental health issues are more vulnerable to experiencing violence at the hands of police. In 2015, 27 percent of police shootings involved a mental health crisis (Oberholtzer 2017). These inequalities by ability—whether due to disability or mental illness—are pervasive throughout the criminal justice system, including in incarceration.

Jails and prisons have been called modern-day asylums because of the high concentration of individuals with mental illnesses. About one-third of people in all federal or state prisons have been diagnosed with a mental illness, most of whom are not receiving treatment (Wang 2022). In some areas, these issues are even more acute. For instance, in Chicago’s Cook County jail, nearly 50 percent of the people incarcerated had some form of mental illness (Cook County Sheriff’s Office 2022).

Incarceration facilities rarely have the resources to address these mental health needs. More than 60 percent of people with a history of mental illness do not receive mental health treatment while incarcerated in state and federal prisons (Bronson and Berzofsky 2017). Even those on treatment regimens before incarceration often cannot continue that treatment once incarcerated. Over 50 percent of individuals taking medication for mental health conditions at admission did not continue to receive their medication once in prison (Reingle Gonzalez and Connell 2014).

It’s important to remember that we cannot talk about how identity impacts individuals’ experiences without taking an intersectional approach to these conversations. For instance, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx transgender people have significantly higher incarceration rates than White transgender people (Jones 2021). This is just one example of how identity is intersectional. To better understand how the criminal justice system impacts people, we must look at all of the different aspects of their identity—gender, race/ethnicity, class, sexuality, citizenship, ability, and other forms of group membership.

Reducing Crime

During the last few decades, the United States has used a get-tough approach to fight crime. This approach has involved longer prison terms and the building of many more prisons and jails. As noted earlier, scholars doubt that this surge in imprisonment has achieved significant crime reduction at an affordable cost, and they worry that it may be leading to greater problems in the future as hundreds of thousands of prison inmates are released back into their communities every year.

Many of these scholars favor an approach to crime borrowed from the field of public health. In the areas of health and medicine, a public health approach tries to treat people who are already ill, but it especially focuses on preventing disease and illness before they begin. While physicians try to help people who already have cancer, medical researchers constantly search for the causes of cancer so that they can try to prevent it before it affects anyone. This model is increasingly being applied to criminal behavior, and criminologists have advanced several ideas that, if implemented with sufficient funds and serious purpose, hold great potential for achieving significant, cost-effective reductions in crime (Barlow & Decker, 2010; Frost, Freilich, & Clear, 2010; Lab, 2010). Many of their strategies rest on the huge body of theory and research on the factors underlying crime in the United States, which we had space only to touch on earlier, while other proposals call for criminal justice reforms. Some of these many strategies are highlighted here.

A first strategy involves serious national efforts to reduce poverty and to improve neighborhood living conditions. It is true that most poor people do not commit crime, but it is also true that most street crime is committed by the poor or near poor for reasons discussed earlier. Efforts that create decent-paying jobs for the poor, enhance their vocational and educational opportunities, and improve their neighborhood living conditions should all help reduce poverty and its attendant problems and thus to reduce crime (Currie, 2011).

A second strategy involves changes in how American parents raise their boys. To the extent that the large gender difference in serious crime stems from male socialization patterns, changes in male socialization should help reduce crime (Collier, 2004). This will certainly not happen any time soon, but if American parents can begin to raise their boys to be less aggressive and less dominating, they will help reduce the nation’s crime rate. As two feminist criminologists have noted, “A large price is paid for structures of male domination and for the very qualities that drive men to be successful, to control others, and to wield uncompromising power.…Gender differences in crime suggest that crime may not be so normal after all. Such differences challenge us to see that in the lives of women, men have a great deal more to learn” (Daly & Chesney-Lind, 1988, p. 527).

A third and very important strategy involves expansion of early childhood intervention (ECI) programs and nutrition services for poor mothers and their children. ECI programs generally involve visits by social workers, nurses, or other professionals to young, poor mothers shortly after they give birth, as these mother’s children are often at high risk for later behavioral problems (Welsh & Farrington, 2007). These visits may be daily or weekly and last for several months, and they involve parenting instruction and training in other life skills. These programs have been shown to be very successful in reducing childhood and adolescent misbehavior in a cost-effective manner (Greenwood, 2006). In the same vein, nutrition services would also reduce the risk of neurological impairment among newborns and young children and thus their likelihood of developing later behavioral problems.

A fourth strategy calls for a national effort to improve the nation’s schools and schooling. This effort would involve replacing large, older, and dilapidated schoolhouses with smaller, nicer, and better equipped ones. For many reasons, this effort should help improve student academic achievement and school commitment and thus lower delinquent and later criminal behavior.

A final set of strategies involves changes in the criminal justice system that should help reduce repeat offending and save much money that could be used to fund the ECI programs and other efforts just outlined. Placing nonviolent property and drug offenders in community corrections (e.g., probation, daytime supervision) would reduce the number of prison and jail inmates by hundreds of thousands annually without endangering Americans’ safety and save billions of dollars in prison costs (Jacobson, 2006). These funds could also be used to improve prison and jail vocational and educational programming and drug and alcohol services, all of which are seriously underfunded. If properly funded, such programs and services hold great promise for rehabilitating many inmates (Cullen, 2007). Elimination of the death penalty would also save much money while also eliminating the possibility of wrongful executions.

This is not a complete list of strategies, but it does suggest the kinds of efforts that would help address the roots of crime and, in the long run, help to reduce it. Although the United States may not be interested in pursuing this crime-prevention approach, strategies like the ones just mentioned would in the long run be more likely than our current get-tough approach to create a safer society and at the same time save us billions of dollars annually.

Note that none of these proposals addresses white-collar crime, which should not be neglected in a discussion of reducing the nation’s crime problem. One reason white-collar crime is so common is that the laws against it are weakly enforced; more consistent enforcement of these laws should help reduce white-collar crime, as would the greater use of imprisonment for convicted white-collar criminals (Rosoff et al., 2010).

Other Models

One way to think about different possibilities for this system is by looking at how other countries have tackled these problems. Using our sociological imagination, we can critically examine our institutions and think more deeply about what we could learn from the different ways crime is addressed around the globe.

Next, we explore three examples of how other countries have addressed criminal justice issues. In these examples, we’ll look at how countries have reformed their systems, effectively addressed recidivism, and created cultures of rehabilitation rather than punishment. In each system, crime is taken seriously, especially violent crime. At the same time, these systems address many of the issues we have examined in the U.S. system.

Policing and Prison in Nordic Countries

Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Sweden, and Norway) have very different systems of policing and imprisonment compared to other wealthy Western nations. While there are differences between each country’s political system, there are many more commonalities in their approach to criminal justice. Foremost, compared to other wealthy Western nations, they have much lower punishment severity, imprisonment rates, and violence rates. The primary focus of these systems is preventing crime from occurring in the first place. When crime does occur, the goal of these systems is to reduce recidivism and restore justice rather than simply punitively punishing an individual for an offense. Nordic countries have strong welfare states. By providing the essential resources that individuals need to survive, fewer individuals turn to criminal activities to make ends meet (Lappi-Seppälä and Tonry 2011). The top picture below shows comparisons between a prison in Iceland and Oregon prisons.

Differences in social policies and lower crime levels between Nordic countries and the United States are not the only factors leading to lower incarceration rates. The structure of the police looks very different in Nordic countries. Unlike in the United States, where police are organized at the state and local levels, all Nordic countries have unified, federally-organized police forces (Lappi-Seppälä and Tonry 2011). From here, the country is divided into police districts that are then overseen by chiefs of police. Police training looks much different in Nordic countries, as well. Police in these countries spend considerably more time being trained and cover topics such as criminological theory, health science, behavioral science, and social work. Use of force against citizens is incredibly low in these countries, with fatal police shootings being rare rather than commonplace, as they are in the United States.

In terms of incarceration, all Nordic countries have abolished the death penalty and only use incarceration for the most serious offenses. Generally, penalties for crimes are less severe in these countries, tending to hold individuals accountable through formal warning, fines, and community sanctions rather than imprisonment. When possible, the goal is for individuals to remain in their communities and access resources including therapy, job training, and other services to prevent individuals from committing crimes again. These policies are incredibly effective. Nordic countries have some of the lowest rates of lethal violence and extremely low levels of recidivism.

Decriminalization of Drugs

There have been multiple countries around the world that have decriminalized drugs, aiming to address inequality created by criminalization policies and to focus on addressing drug addiction as a health issue. Uruguay has decriminalized personal possession of all drugs since 1974. Uruguay took this one step further in 2013, becoming the first country in the world to fully legalize cannabis and establish a regulatory framework for its sale. Similar policies can be seen in places like Portugal, where drugs have been decriminalized since 2001. In the decades since, there have been significant increases in the number of people voluntarily entering drug treatment, while they have seen decreases in several negative drug-related outcomes, such as overdoses, HIV infections, problematic drug use, and incarceration. In both of these countries, drug trafficking is still heavily criminalized, but people who use drugs every day are now more likely to be connected to health resources or (at the very least) not face the prospect of incarceration for possession of a personal stash of drugs. These examples of policy interventions helped inspire Measure 110 in Oregon, which established similar decriminalization, meaning people possessing a personal amount would not face serious criminal charges and could more easily gain access to drug treatment.

References

Barkan, S. E. (1996). The social science significance of the O. J. Simpson case. In G. Barak (Ed.), Representing O. J.: Murder, criminal justice and mass culture (pp. 36–42). Albany, NY: Harrow and Heston.

Barlow, H. D., & Decker, S. H. (Eds.). (2010). Criminology and public policy: Putting theory to work. Philadelphia, PA: Temple Univeristy Press.

Bjerk, David. 2016. “Mandatory Minimum Policy Reform and the Sentencing of Crack Cocaine Defendants: An Analysis of the Fair Sentencing Act.” IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 10237.

Bronson, Jennifer, and Marcus Berzofsky. 2017. “Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011-12.” US Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics. Special Report NCJ 250612. (https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf).

Cook County Sheriff’s Office. 2022. “Criminalization of Mental Illness.” Retrieved Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.cookcountysheriff.org/cr...ental-illness/).

Cullen, F. T. (2007). Make rehabilitation corrections’ guiding paradigm. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(4), 717–727.

Currie, E. (2011). On the pitfalls of spurious prudence. Criminology & Public Policy, 10, 109–114.

Czerny, M. and J. Swift. (1988). Getting started on social analysis in Canada (2nd Edition). Between the Lines Press.

Daly, K., & Chesney-Lind, M. (1988). Feminism and criminology. Justice Quarterly, 5, 497–538.

Death Penalty Information Center. (2025). Facts about the death penalty. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/documents/FactSheet.pdf.

Desilver, Drew, Michael Lipka, and Dalia Fahmy. 2020. “10 Things We Know About Race and Policing in the U.S.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved on Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/03/10-things-we-know-about-race-and-policing-in-the-u-s/).

Fridell, Lorie, and Hyeyoung Lim. 2016. “Assessing the Racial Aspects of Police Force Using the Implicit and Counter-Bias Perspectives.” Journal of Criminal Justice 44: 36-48. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.12.00.

Frost, N. A., Freilich, J. D., & Clear, T. R. (Eds.). (2010). Contemporary issues in criminal justice policy: Policy proposals from the American society of criminology conference. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Gramlich, John. 2019. “The Gap Between the Number of Blacks and Whites in Prison is Shrinking.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved on Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/30/shrinking-gap-between-number-of-blacks-and-whites-in-prison/).

Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jackson Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. 2011. “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.” National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce. Retrieved Aug. 14, 2022. (https://transequality.org/sites/defa...TDS_Report.pdf).

Greenwood, P. W. (2006). Changing lives: Delinquency prevention as crime-control policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hakim, D. (2006, June 29). Judge urges state control of legal aid for the poor. New York Times, p. B1.

Hernandez, Cesar Cuauhtemoc Garcia. 2022. Crimmigration Law, Second Edition. American Bar Association.

Institute for Criminal Policy Research. 2024. “World Prison Brief: Highest to Lowest-Prison Population Total.” Retrieved February 29, 2020. http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest...xonomy_tid=All.

Jacobson, M. (2006). Reversing the punitive turn: The Limits and promise of current research. Criminology & Public Policy, 5, 277–284.

Jones, Alexi. 2021. “Visualizing the Unequal Treatment of LGBTQ People in the Criminal Justice System.” Prison Policy Institute. Retrieved Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/03/02/lgbtq/).

Kappeler, V. E., & Potter, G. W. (2005). The mythology of crime and criminal justice (4th ed.). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

King, Ryan, and Marc Mauer. 2005. “The War on Marijuana: The Transformation of the War on Drugs in the 1990s.” The Sentencing Project. Retrieved on Aug 14, 2022. (https://www.sentencingproject.org/pu...-in-the-1990s/).

Kramer, A., Guillory, J. and Hancock, J. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive–scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111 (24), 8788–8790. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111

Lappi-Seppälä, Tapio, and Michael Tonry. 2011. “Crime, Criminal Justice, and Criminology in the Nordic Countries.” Crime and Justice 40(1):1-32. doi:10.1086/660822.

Meyer, Ilan H., Andrew R. Flores, Lara Stemple, Adam P. Romero, Bianca D. M. Wilson, and Jody L. Herman. 2017. “Incarceration Rates and Traits of Sexual Minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012.” American Journal of Public Health 107(2): 267-273. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303576.

Oberholtzer, Elliot. 2017. “Police, Courts, Jails, and Prisons All Fail Disabled People” Prison Policy Institute. Retrieved on Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/08/23/disability/).

Oh, O., Agrawal, M. and Raghav Rao, H. (2013, June). Community intelligence and social media services: A rumor theoretic analysis of tweets during social crises. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.05

Oppel, R. A., Jr. (2011, September 26). Sentencing shift gives new leverage to prosecutors. New York Times, p. A1.

Paternoster, R., & Brame, R. (2008). Reassessing race disparities in Maryland capital cases. Criminology, 46, 971–1007.

Pröllochs, N., Bär, D. and Feuerriegel, S. (2021, November 22). Emotions explain differences in the diffusion of true vs. false social media rumors. Scientific Reports, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01813-2

Quinney, R. (1977). Class, state and crime: On the theory and practice of criminal justice. Longman.

Reingle Gonzalez, Jennifer M., and Nadine M. Connell. 2014. “Mental Health of Prisoners: Identifying Barriers to Mental Health Treatment and Medication Continuity.” American Journal of Public Health 104(12): 2328-2333. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302043.

Roscigno, Vincent J., and Kayla Preito-Hodge. 2021. “Racist Cops, Vested “Blue” Interests, or Both? Evidence from Four Decades of the General Social Survey.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 7, doi: 10.1177/2378023120980913.

Rosoff, S. M., Pontell, H. N., & Tillman, R. (2010). Profit without honor: White collar crime and the looting of America (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rosoff, S. M., Pontell, H. N., & Tillman, R. (2010). Profit without honor: White collar crime and the looting of America (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schwartz, J., & Fitzsimmons, E. G. (2011, March 10). Illinois governor signs capital punishment ban. New York Times, p. A18.

Schwartz, J., & Fitzsimmons, E. G. (2011, March 10). Illinois governor signs capital punishment ban. New York Times, p. A18.

Sharara, Fablina, Eve E. Wool, et al.. 2021. “ Fatal Police Violence by Race and State in the USA, 1980–2019: A Network Meta-Regression.” The Lancet 398(10307): 1239-1255. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01609-3.

Stieglitz, S. and Dang–Xuan, L. (2013). Emotions and information diffusion in social media—sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. Journal of Management Information Systems, 29(4), 217–248. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222290408

The Sentencing Project. 2021. “Private Prisons in the United States.” The Sentencing Project. Retrieved on Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.sentencingproject.org/pu...united-states/).

The Sentencing Project. 2022. “Incarcerated Women and Girls.” The Sentencing Project. Retrieved on Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp...-and-Girls.pdf).

Vagins, Deborah, and Jesselyn McCurdy. 2006. “Cracks in the System: Twenty Years of the Unjust Federal Crack Cocaine Law.” American Civil Liberties Union Monograph.

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., and Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Wang, Leah. 2022. “Chronic Punishment: The Unmet Health Needs of People in State Prison” Prison Policy Institute. Retrieved on Aug. 14, 2022. (https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/chronicpunishment.html#mentalhealth).

Welsh, B. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2007). Save children from a life of crime. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(4), 871–879.

Welsh, B. C., & Farrington, D. P. (Eds.). (2007). Preventing Crime: What works for children, offenders, victims and places. New York, NY: Springer.

Sources

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/economicsforthegreatergood /

https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_...ty-and-change/

https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Cosumnes_River_College/SOC_301%3A_Social_Problems_(Lugo)/

https://2012books.lardbucket.org/boo...cial-problems/

https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/soceveryday1e/

https://openpress.usask.ca/soc112/

https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology3rdedition/

https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/economicsforthegreatergood/chapter/the-economics-of-crime/

https://cod.pressbooks.pub/criminology/chapter/social-class-and-crime/