5.1: What is a Primate?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 66773

Primates are one of at least twenty Orders belonging to the Class Mammalia. All members of this class share certain characteristics, including, among other things, having fur or hair, producing milk from mammary glands, and being warm-blooded. There are three types of mammals: monotremes, marsupials, and placental mammals. Monotremes are the most primitive of the mammals, meaning they have retained more ancient traits than marsupials or placental mammals, and so, monotremes are characterized by some unusual traits. Monotremes, which include echidnas and duck-billed platypuses, lay eggs rather than give birth to live young. Once the young hatch, they lap up milk produced from glands on the mother’s abdomen rather than latch onto nipples. Marsupial mammals are those, like kangaroos and koalas, who internally gestate for a very short period of time and give birth to relatively undeveloped young. Joeys, as these newborns are called, complete their growth externally in their mother’s pouch where they suckle. Lastly, there are placental mammals. Placental mammals internally gestate for a longer period of time and give birth to fairly well-developed young who are then nursed. Primates, including ourselves, belong to this last group. Among the diversity of mammalian orders alive today, primates are very likely one of the oldest. One genetic estimate puts the origin of primates at approximately 91 million years ago (mya), predating the extinction of the dinosaurs (Bininda-Emonds et al. 2007). Today, the Order Primates is a diverse group of animals that includes lemurs and lorises, tarsiers, monkeys of the New and Old Worlds, apes, and humans, all of which are united in sharing a suite of anatomical, behavioral, and life history characteristics. Before delving into the specific traits that distinguish primates from other animals, it is important to first discuss the different types of traits that we will encounter.

Types of Traits

When evaluating relationships between different groups of primates, we use key traits that allow us to determine which species are most closely related to one another. Traits can be either primitive or derived. Primitive traits are those that a taxon has because it has inherited the trait from a distant ancestor. For example, all primates have body hair because we are mammals and all mammals share an ancestor hundreds of millions of years ago that had body hair. This trait has been passed down to all mammals from this shared ancestor, so all mammals alive today have body hair. Derived traits are those that have been more recently altered. This type of trait is most useful when we are trying to distinguish one group from another because derived traits tell us which taxa are more closely related to each other. For example, humans walk on two legs. The many adaptations that humans possess which allow us to move in this way evolved after humans split from the Genus Pan. This means that when we find fossil taxa that share derived traits for walking on two legs, we can conclude that they are likely more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees and bonobos.

There are a couple of other important points about primitive and derived traits that will become apparent as we discuss primate diversity. First, the terms primitive and derived are relative terms. This means that depending on what taxa are being compared, a trait can be either one. For example, in the previous section, body hair was used as an example for a primitive trait among primates. All mammals have body hair because we share a distant ancestor who had this trait. The presence of body hair therefore doesn’t allow you to distinguish whether monkeys are more closely related to apes or lemurs because they all share this trait. However, if we are comparing mammals to birds and fish, then body hair becomes a derived trait of mammals. It evolved after mammals diverged from birds and fish, and it tells us that all mammals are more closely related to each other than they are to birds or fish. The second important point is that very often when one lineage splits into two, one taxon will stay more similar to the last common ancestor in retaining more primitive traits, whereas the other lineage will usually become more different from the last common ancestor by developing more derived traits. This will become very apparent when we discuss the two suborders of primates, Strepsirrhini and Haplorrhini.When these two lineages diverged, strepsirrhines retained more primitive traits (those present in the ancestor of primates) and haplorrhines developed more derived traits (became more different from the ancestor of primates).

There are two other types of traits that will be relevant to our discussions here: generalized and specialized traits. Generalized traits are those characteristics that are useful for a wide range of things. Having opposable thumbs that go in a different direction than the rest of your fingers is a very useful, generalized trait. You can hold a pen, grab a branch, peel a banana, or text your friends all thanks to your opposable thumbs. Specialized traits are those that have been modified for a specific purpose. These traits may not have a wide range of uses, but they will be very efficient at their job. Hooves in horses are a good example of a specialized trait. Horses cannot grasp objects with their hooves, but hooves allow horses to run very quickly on the ground on all fours. You can think of generalized traits as a Swiss Army knife, useful for a wide range of tasks but not particularly good at any of one them. That is, if you’re in a bind, then a Swiss Army knife can be very useful to cut a rope or fix a loose screw, but if you were going to build furniture or fix a kitchen sink, then you’d want specialized tools for the job. As we will see, most primate traits tend to be generalized.

Primate Suite of Traits

The Order Primates is distinguished from other groups of mammals in having a suite of characteristics. This means that there is no individual trait that you can use to instantly identify an animal as a primate; instead, you have to look for animals that possess a collection of traits. What this also means is that each individual trait we discuss may be found in non-primates, but if you see an animal that has most or all of these traits, there is a good chance it is a primate.

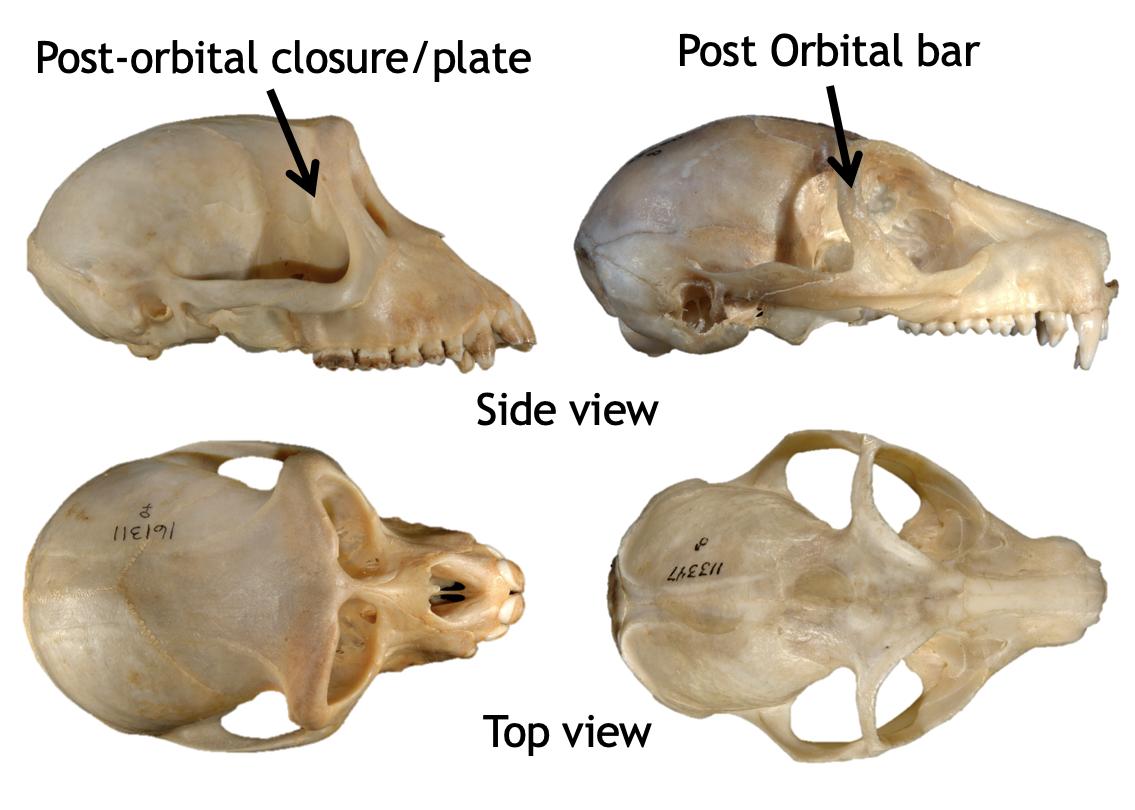

One area in which the Order Primates is most distinguished from other organisms regards traits related to our senses, especially our vision. Compared to other animals, primates rely on vision as a primary sense. Our heavy reliance on vision is reflected in many areas of our anatomy and behavior. All primates have eyes that face forward with convergent (overlapping) visual fields. This means that if you cover one eye with your hand, you can still see most of the room with your other one. This also means that we cannot see on the sides or behind us as well as some other animals can. In order to protect the sides of the eyes from the muscles we use for chewing, all primates have at least a postorbital bar, a bony ring around the outside of the eye (Figure 5.1). Some primate taxa have more convergent eyes than others, so those primates need extra protection for their eyes. As a result, animals with greater orbital convergence will have a postorbital plate orpostorbital closure in addition to the bar (Figure 5.1). The postorbital bar is a derived trait of primates, appearing in our earliest ancestors, which you will read more about in Chapter 8.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): All primates have some form of bony protection around their eyes. Some have a postorbital bar only (right), but many have full postorbital closure, also called a postorbital plate, that completely protects the back of the eye socket (left).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): All primates have some form of bony protection around their eyes. Some have a postorbital bar only (right), but many have full postorbital closure, also called a postorbital plate, that completely protects the back of the eye socket (left).Another important and distinctive trait of our Order is that many primates have trichromatic color vision, the ability to distinguish reds and yellows in addition to blues and greens. Interestingly, birds, fish, and reptiles are tetrachromatic (they can see reds, yellows, blues, greens, and even ultraviolet), but most mammals, including some primates, are only dichromatic (they see only in blues and greens). It is thought that the nocturnal ancestors of mammals benefited from seeing better at night rather than in color, and so dichromacy is thought to be the primitive condition for mammals. There is a lot of interest in why some primates would re-evolve trichromacy. Some theories revolve around food, arguing that the ability to see reds/yellows may allow primates who can see these colors to better detect young leaves (Dominy and Lucas 2001) or ripe fruits (Regan et al. 2001) against an otherwise green, leafy background. Color vision has also been suggested to be useful for detecting predators, especially big cats (Pessoa et al. 2014). Another theory emphasizes the usefulness of trichromacy in social and mate-choice contexts (Changizi et al. 2006). Thus far there is no consensus, as trichromatic color vision can be useful in many circumstances. There is also the added complication that sometimes dichromacy is more advantageous, as animals who are dichromatic are usually better at seeing through camouflage to find hidden items like foods or predators (Morgan et al. 1992). Therefore, investigating the evolution of color vision continues to be an interesting and ongoing area of research.

Primates also differ from other mammals in the size and complexity of our brains. All primates have brains that are larger than you would expect when compared to other mammals of the same size. On average, primates have brains that are twice as big for their body size as you would expect when compared to other mammals. Not unexpectedly, the visual centers of the brain are larger in primates and the wiring is different from that in other animals, reflecting our reliance on this sense. The neocortex, which is used for higher functions like consciousness and language in humans, as well as sensory perception and spatial awareness, is also larger in primates relative to other animals. In non-primates this part of the brain is often smooth, but in primates it is made up of many folds which increase the surface area. It has been proposed that the more complex neocortex of primates is related to diet, with fruit-eating primates having larger relative brain sizes than leaf-eating primates, due to the more challenging cognitive demands required to find and process fruits (Clutton‐Brock and Harvey 1980). An alternative hypothesis argues that larger brain size is necessary for navigating the complexities of primate social life, with larger brains occurring in species who live in larger, more complex groups relative to those living in pairs or solitarily (Dunbar 1998). There seems to be support for both hypotheses, as large brains are a benefit under both sets of selective pressures.

The primate visual system uses a lot of energy, so primates have compensated by cutting back on other sensory systems, particularly our sense of smell. Compared to other mammals, primates have relatively reduced snouts. This is another derived trait of primates that appears even in our earliest ancestors. As we will discuss, there is variation across primate taxa in how much snouts are reduced. Those with a better sense of smell usually have poorer vision than those with a relatively dull sense of smell. The reason for this is that all organisms have a limited amount of energy to spend on running our bodies, so we make , because energy spent on one trait must mean cutting back on energy spent on another. With regards to primate senses, primates with better vision (more convergent eyes, better visual acuity, etc.) are spending more energy on vision and thus will have poorer smell (and a shorter snout). Primates who spend less energy on vision (less convergent eyes, poorer visual acuity, etc.) will have a better sense of smell (and a longer snout).

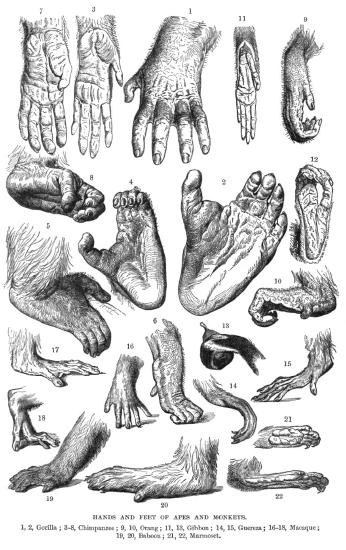

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): These drawings of the hands and feet of different primates clearly show the opposable thumbs and big toes, pentadactyly, flattened nails, and tactile pads that are characteristic of our Order.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): These drawings of the hands and feet of different primates clearly show the opposable thumbs and big toes, pentadactyly, flattened nails, and tactile pads that are characteristic of our Order.Primates also differ from other animals in our hands and feet. The Order Primates is a largely arboreal taxonomic group, which means that most primates spend a significant amount of their time in trees. As a result, the hands and feet of primates have evolved to move around in a three-dimensional environment. Primates have the generalized trait of pentadactyly— possessing five digits (fingers and toes) on each limb. Many non-primates, like dogs and horses, have fewer digits because they are specialized for high-speed, terrestrial (on the ground) running. Pentadactyly is also a primitive trait, one that dates back to the earliest four-footed animals. Primates today have opposable thumbs and, except humans, opposable big toes (Figure 5.2). are a derived trait that appeared in the earliest primates about 55 million years ago. Having thumbs and big toes that go in a different direction from the rest of the fingers and toes allow primates to be excellent climbers in trees but also allow us to manipulate objects. Our ability to manipulate objects is further enhanced by the flattened nails on the backs of our fingers and toes that we possess in the place of the claws and hooves that many other mammals have. On the other side of our digits, we have sensitive tactile pads that allow us to have a fine sense of touch. Primates use this fine sense of touch for handling food and, in many species, grooming themselves and others. In primates, grooming is an important social currency, through which individuals forge and maintain social bonds. You will learn more about grooming in Chapter 6.

Animals with large brains usually have extended life history patterns, and primates are no exception. Life history refers to the pace at which an organism grows, reproduces, ages, and so forth. Some animals grow very quickly and reproduce many offspring in a short time frame, but do not live very long. Other animals grow slowly, reproduce few offspring, reproduce infrequently, and live a long time. Primates are all in the “slow lane” of life history patterns. Compared to animals of similar body size, primates grow and develop more slowly, have fewer offspring per pregnancy, reproduce less often, and live longer. Primates also invest heavily in each offspring, a subject you will learn more about in the next chapter. With a few exceptions, most primates only have one offspring at a time. There is a group of small-bodied monkeys in the New World who regularly give birth to twins, and some lemurs are able to give birth to multiple offspring at a time, but these primates are the exception rather than the rule. Primates also reproduce relatively infrequently. The fastest-reproducing primates will produce offspring about every six months, while the slowest, the orangutan, reproduces only once every seven to nine years. This very slow reproductive rate makes the orangutan the slowest-reproducing animal on the planet! Primates are also characterized by having long lifespans. The group that includes humans and large-bodied apes has the most extended life history patterns among all primates, with some large-bodied apes estimated to live up to 58 years in the wild (Robson et al. 2006).

Lastly, primates share some behavioral and ecological traits. Primates are very social animals, and all primates, even those that search for food alone, have strong social networks with others of their species. Indeed, social networks in primates have been shown to be crucial in times of stress and to enhance reproductive success (Silk et al. 2009). Unlike many animals, primates do not migrate. This means that primates stay in a relatively stable area for their whole life, often interacting with the same individuals for their long lives. The long-term relationships that primates form with others of their species lead to complex and fascinating social behaviors, which you will read about in Chapter 6. Finally, non-human primates show a clear preference for tropical regions of the world. Most primates are found between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, with only a few taxa living outside of these regions. You can see a summary of the primate suite of traits in Figure 5.3.

|

Primate suite of traits |

|

Convergent eyes Post-orbital bar Many have trichromatic color vision Short snouts Opposable thumbs and big toes Pentadactyly Flattened nails Tactile pads Highly arboreal Large brains Extended life histories Live in the tropics |