Linguistic Anthropology

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) - Repartition map of the languages over the world

"It is quite an illusion to imagine that one adjusts to reality essentially without the use of language and that language is merely an incidental means of solving specific problems of communication or reflection" – Edward Sapir

As implied from the quote above language and communication are key components of the human experience. Language can be one of the easiest ways to make connections with other people. It helps us quickly identify the groups to which we belong. It is how we convey information from one generation to the next. But language is only one way that humans communicate with one another. Non-verbal forms of communication are as important if not more so. (The Human Face episode 4: www.youtube.com/watch?v=jh047M5pHGY-à). Linguistic anthropology is the sub-discipline that studies communication systems, particularly language. Using comparative analysis, linguistic anthropologists examine the interaction of language and culture. They look at the connection between language and thought and how it informs about social values and norms. Linguistic data has been used to examine worldview, migration patterns, origins of peoples, etc.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) - Edward Sapir (1184-1939)

Language

Language is a set of arbitrary symbols shared among a group. These symbols may be verbal, signed, or written. It is one of the primary ways that we communicate, or send and receive messages. Non-verbal forms of communication include body language, body modification, and appearance (what we wear and our hairstyle).

Even non-human primates have a communication system; the difference, as far as we can determine, is that non-human primates use a call system, which is a system of oral communication that uses a set of sounds in response to environmental factors, e.g., a predator approaching. They can only signal one thing at a time. For instance, ‘here is food,’ or ‘a leopard is attacking.’ They cannot signal something like ‘I’ve found food but there’s a leopard here so run away.’

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) - Chimpanzee vocalizing.

However, primatologists conducting communication studies with great apes raise questions about the great apes’ ability to communicate. Primatologists like Susan Savage-Rumbaugh, Sally Boysen, and Francine “Penny” Patterson report that they have been able to have human-like communication with bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas through sign language, even conveying feelings like sympathy. Washoe was the first chimpanzee to learn American Sign Language. Washoe, who was rescued in the wild after her mother was killed by poachers, learned over three hundred signs, some of which she taught to her adopted son, Loulis, without any help from human agents. She also told jokes, lied, and swore. Other great apes like Koko, a western lowland gorilla born at the San Francisco Zoo, have demonstrated linguistic displacement, which is the ability to talk about things that are not present or even real, by signing for her kitten when it was not present. She also displayed mourning behavior after being told that actor and comedian Robin Williams died (read more about Koko’s reaction in this Huffington Post article, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/13/koko-gorilla-robin-williams_n_5675300.html).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) - Chinese man with plaid hat and pompoms

Linguistic displacement has long been identified as a hallmark of human communication, something that set it apart from non-human primate communication. Coupled with productivity, human language systems do appear to be more complex then our non-human primate cousins. Productivity refers to “the ability to create an infinite range of understandable expressions from a finite set of rules” (Miller 2011: 206). Using combinations of symbols, facial expressions, sounds, written word, signs, and body language, humans can communicate things in a myriad of ways (for a humorous look at facial expressions, check out “What a Girl’s Facial Expressions Mean” on YouTube [youtu.be/KAJvUXkIBeo]).

All cultures have language. Most individuals within that culture are fully competent users of the language without being formally taught it. One can learn a language simply by being exposed to it, which is why foreign language teachers espouse immersion as the best way to learn.

No one language has more efficient grammar than another, and there is no correlation between grammatical complexity and social complexity; some small, homogenous cultures have the most complex language. In December 2009, The Economist named the Tuyuca language the “hardest” language. The Tuyuca live in the eastern Amazon. It is not as hard to speak as some other languages as there are simple consonants and a few nasal vowels; however, it is an agglutinative language, so the word hóabãsiriga means “I do not know how to write.” Hóabãsiriga has multiple morphemes each of which contribute to the word’s meaning. A morpheme is the smallest sound that has meaning. Consider the word ‘cow.’ It is a single morpheme—if we try to break the word down into smaller sound units it has no meaning. Same with the word ‘boy.’ Put them together and we have a word with two morphemes (O’Neil 2013). Morphemes are a part of morphology, which is the grammatical category of analysis concerned with how sounds, or phonemes, are combined. Morphemes are combined into strings of sounds to create speech, which is grouped into sentences and phrases. The rules that govern how words should be combined are called syntax, which is the second of two grammar categories of analysis. In Tuyuca, all statements require a verb-ending to indicate how the speaker knows something. For instance, diga ape-wi means that the speaker knows the boy played soccer because of direct observation, but diga ape-hiyi means that the speaker assumed the boy played soccer. Tuyuca has somewhere between fifty and one hundred forty noun classes based on gender, compared to Spanish which has two noun classes that are based on gender.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) - A Saami family,Norway, 1890s.

Every language has a lexicon, or vocabulary. Semantics is the study of a language meaning system. Anthropologists are particularly interested in ethnosemantics, which is the study of semantics within a specific cultural context. Ethnosemantics helps anthropologists understand how people perceive, define, and classify their world. Focal vocabularies are sets of words that pertain to important aspects of the culture. For example, the Saami, the indigenous reindeer hunters in Scandinavia, have numerous words for reindeer, snow, and ice. Snow and ice terminology is based on the physical condition of the layers as well as changes due to weather and temperature. Reindeer terminology is based primarily on sex, age, color, and appearance of various body parts, but may be based on others things such as personality and habits.

Table 5 - Saami Reindeer terminology based on personality and habits (Magga 2006)

|

Biltu

|

Shy and wild, usually refers to females

|

|

Doalli

|

Apt to resist

|

|

Goaisu

|

Male reindeer who keeps apart all summer and is very fat when autumn comes

|

|

Já?as

|

Obstinate, difficult to lead

|

|

Láiddas

|

Easy to lead by a rope or rein

|

|

Lojat

|

Very tractable driving-reindeer

|

|

Lojáš

|

Very tame female reindeer

|

|

Láiddot

|

Reindeer which is very láiddas

|

|

Moggaraš

|

Female reindeer who slips the lasso over head in order to avoid being caught

|

|

Njirru

|

Female reindeer which is very unmanageable and difficult to hold when tied

|

|

Ravdaboazu

|

Reindeer which keeps itself to the edge of the herd

|

|

Sarat

|

Smallish male reindeer which chases a female out of the herd in order to mate with it

|

|

Šlohtur

|

Reindeer which hardly lifts its feet

|

|

Stoalut

|

Reindeer which is no longer afraid of the dog

|

Table 6 - Saami Terminology for Condition and Layers of Snow (Magga 2006)

|

Čahki

|

Hard lump of snow; hard snowball

|

|

Geardni

|

Thin crust of snow

|

|

Gska-geardi

|

Layer of crust

|

|

Gaska-skárta

|

Hard layer of crust

|

|

Goahpálat

|

The kind of snowstorm in which the snow falls thickly and sticks to things

|

|

Guoldu

|

A cloud of snow which blows up from the ground when there is a hard frost without very much wind

|

|

Luotkku

|

Loose snow

|

|

Moarri

|

Brittle crust of snow; thin crust of ice

|

|

Njáhcu

|

Thaw

|

|

Ruokna

|

Thin hard crust of ice on snow

|

|

Seanaš

|

Granular snow at the bottom of the layer of snow

|

|

Skárta

|

Thin layer of snow frozen on to the ground

|

|

Skáva

|

Very thin layer of frozen snow

|

|

Skávvi

|

Crust of ice on snow, formed in the evening after the sun has thawed the top of the snow during the day

|

|

Soavli

|

Very wet, slushy snow, snow-slush

|

|

Skoavdi

|

Empty space between snow and the ground

|

|

Vahca

|

Loose snow, especially new snow on the top of a layer of older snow or on a road with snow on it

|

Non-Verbal Communication

Cultures also have non-verbal forms of communication, but there are still rules and symbols involved. Kinesics is the study of communication through body language, including gestures, facial expressions, body movement, and stances. Hand gestures add emphasis; a facial expression may contradict verbal communication. Voice level and tone add to our communication. Even silence can be an effective form of communication.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) - Brazil vs. Chile in Mineirão 17.

Body language is culture specific. The same body postures and gestures can have different meanings in different cultures. For instance, holding your hand out, fingers together, and palm facing outward is a symbol for stop in North America. In Greece, the same gesture is highly insulting. Crossing your fingers for luck in North America is an obscene gesture in Vietnam where the crossed fingers are thought to resemble female genitalia. A thumbs-up in North America might mean approval, but in Thailand it is a sign of condemnation usually used by children similar to how children in the United States stick out their tongue. The A-OK symbol gesture of index finger placed on the thumb might mean everything is OK in the United Kingdom and United States, but in some Mediterranean countries, Germany, and Brazil it is the equivalent of calling someone an ass.

Bowing in Japan communicates many things depending on how it is done. Ojigi, or Japanese bowing, is used as a greeting, a way to apologize, and a way to show respect. The degree of the bow indicates the amount of respect. Fifteen degrees is the common greeting bow for those you already know or are on an equal social level. A thirty-degree bow is used for people who have a higher social rank, such as a boss, but not someone to whom you are related. The highest respect bow is forty-five degrees and used when you apologize.

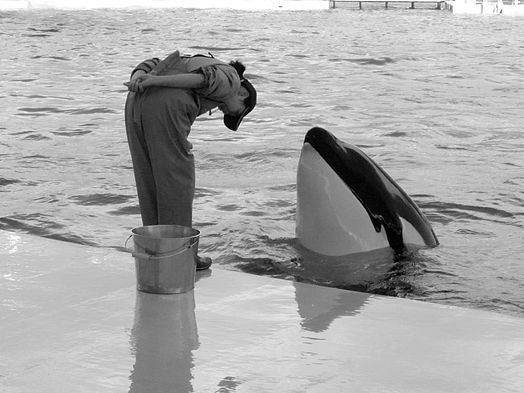

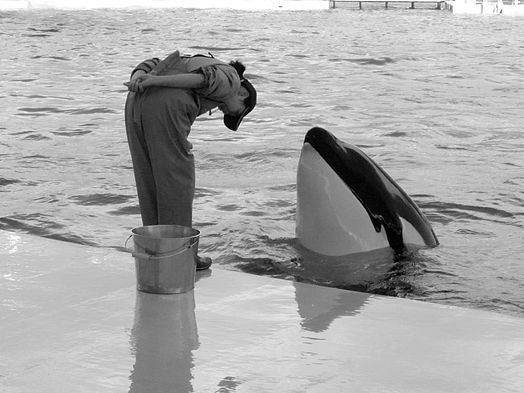

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) - Woman bowing to whale.

Other forms of non-verbal communication include clothing, hairstyles, eye contact, even how close we stand to one another. Proxemics is the study of cultural aspects of the use of space. This can be both in an individual’s personal and physical territory. The use of color in one’s physical space is an example of proxemics of physical territory. A health spa is more likely to use soothing, cool greens and blues rather than reds and oranges to create a relaxing atmosphere. Personal territory refers to the “bubble” of space we keep between others and ourselves. This varies depending on the other person and the situation, for instance, in the United States public space is defined as somewhere between twelve to twenty-five feet, and is generally adhered to in public speaking situations. Social space, used between business associates and social space such as bus stops, varies between four and ten feet. Personal space is reserved for friends and family, and queues, and ranges between two and four feet. Intimate space is less than a foot and usually involves a high probability of touching. We generally feel uncomfortable or violated if any of these spaces are “invaded” without an invitation.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) - Personal Spaces in Proxemics

Models of Language and Culture

There are two models used in anthropology to study language and culture. In the early twentieth century, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf proposed that language influences the way we think. This idea, known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, is the foundation of the theory of linguisticdeterminism, which states that it is impossible to fully learn or understand a second language because the primary language is so fully ingrained within an individual. Consequently, it is impossible to fully understand other cultures. The Saami concepts of snow listed above serves as an example of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Someone from the desert or the tropics who has never experienced snow cannot think about snow. Try to imagine how you would explain snow to someone who had never experienced snow. It would be necessary to start with a common frame of reference and try to move on from there, but it would be difficult if not impossible to explain snow.

The second model is sociolinguistics. This is the study of how language is shaped within its cultural context; it is basically how people use language. This approach has been instrumental in demonstrating how language is used in different social, economic, and political situations. Sociolinguists contend that language reflects social status, gender, ethnicity, and other forms of social diversity. In the United States, ethnicity can be expressed through the use of specific words and patterns of speech, e.g., Black English Vernacular (BEV), African American English (AAE), or African American Vernacular English (AAVE). AAE is used by many African American youth, particularly in urban centers and conveys an immediate sense of belonging to a group. AAE grew out of slavery and thus carries the prejudice and discrimination associated with that practice. People speaking AAE instead of American Mainstream English (AME) are often seen as less intelligent and less educated. You can learn more about AAE at http://www.pbs.org/speak/seatosea/americanvarieties/AAVE/.

Languages often blend when two cultures that do not speak the same language come into contact creating a pidgin language. Many pidgin languages emerged through the process of European colonialism. Bislama (Vanuatu) and Nigerian Pidgin are two examples. Creole languages evolve from pidgin languages. They have a larger vocabulary and more developed grammar. It becomes the mother tongue of a people. Tok Pisin was a pidgin language in Papua New Guinea, but is now an officially recognized language in that country. Other examples of creole languages include Gullah, Jamaican Creole, and Louisiana Creole. Some confusion can arise with the terms pidgin and creole. In linguistic anthropology they are technical terms as defined above. How culture groups and individuals use the term can be different. Jamaicans do not refer to their language as creole, but as patwa. People speaking Hawai’I Creole English call their language pidgin.

Regional dialects frequently emerge within specific areas of countries. Regional dialects may have specific words, phrases, accents, and intonations by which they are identified. In the United States what you call a fizzy, highly sugared beverage (soda, pop, Coke) can indicate if you are from the South, Midwest or other region (check out www4.ncsu.edu/~jakatz2/project-dialect.html for an interactive map of regional words and phrases for the U.S.). Speaking Cockney, Brummy, or Geordie will immediately inform people of where you are from in Great Britain.

Gender status and roles can be highlighted by language. In the United States, white Euro-American females have three prominent patterns (Miller 2011: 269):

- Politeness

- Rising intonation at the end of sentences

- Frequent use of tag questions (questions placed at the end of sentences seeking affirmation, e.g., "It's a nice day, isn't it?"

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) - Kogals in Japan.

In Japan, female speech patterns also are more polite than males. An honorific “o-“ is attached to nouns, making their speech more refined, e.g., a book is hon for males and ohon for females. Young Japanese females, or kogals, use language and other forms of communication to shake up the traditional feminine roles. They use masculine forms of words, talk openly about sex, and are creating new words using compounds. Heavily influenced by globalization, the kogals are rethinking their traditional roles in Japanese society.

Language can give us clues as to what is taboo within a society or what makes people uncomfortable without anyone specifically telling us. Euphemisms are words or phrases used to indirectly infer to a taboo or uncomfortable topic, such as body parts related to sexual intercourse, pregnancy, disability, mental illness, body shape, and socioeconomic status. Even underclothes have euphemisms…unmentionables, pants, and underpants. Political correctness is a form of euphemism. Disabled is “differently abled,” “sex worker” instead of prostitute, and “Caucasian” instead of white people. Minced oaths are another form of euphemism. These euphemisms reword rude words like “pissed off” into such things as teed off and kissed off.

Euphemisms occur in all languages. Through repeated use they often lose their effectiveness and become a direct part of speech. Euphemisms for sexual intercourse like consummation, copulation, and intercourse itself become commonplace and must be replaced with new euphemisms. This is a good example of how language changes as cultures change. Changes can reflect new conflict and concerns within a culture. Languages can also go extinct. Recent research suggests that of the approximate 6,700 languages spoken in the word today, about 3,500 of them will be extinct by the year 2100 (Solash 2010). In fact, it is estimated that one indigenous language goes extinct every two weeks (Gezen and Kottak 2014). While this may make communication easier between people, a vast amount of knowledge will be lost. More information on endangered indigenous languages can be found at Living Tongues, Institute for Endangered Languages (http://livingtongues.org/).

References

Bilaniuk, Laada. “Anthropology, Linguistic.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 1, edited by William A. Darity, Jr., p. 129-130. Detroit: Macmillian Reference, USA, 2008.

Gezen, Lisa and Conrad Kottak. Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014.

Hughes, Geoffrey. “Euphemisms.” In An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-Speaking World, p. 151-153. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2006.

Magga, Ole Henrik. “Diversity in Saami Terminology for Reindeer, Snow, and Ice.” International Social Science Journal 58, no. 187 (2006): 25-34. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2451.2006.00594.x

Miller, Barbara. Cultural Anthropology, 6th edition. Boston: Prentice Hall, 2011.

O’Neil, Dennis. “Language and Culture: An Introduction to Human Communication.” Last updated July 2013. anthro.palomar.edu/language/Default.htm.

Purdy, Elizabeth. “Ape Communication.” In Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Vol. 1, edited by H. James Birx, p. 214-215. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2006.

School of Languages, Cultures, and Linguistics. “Language Varieties.” University of New England (Australia). Accessed April 29, 2015. www.hawaii.edu/satocenter/langnet/definitions/index.html.

Sheppard, Mike. “Proxemics.” Last updated July 1996. http://www.cs.unm.edu/~sheppard/proxemics.htm.

Solash, Richard. “Silent Extinction: Language Loss Reaches Crisis Levels.” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. Last updated April 29, 2015. http://www.rferl.org/content/Silent Extinction_Language_Loss_Reaches_Crisis_Levels/1963070.html.

The Economist. “Tongue Twisters.” The Economist, December 19, 2009.