This section is not meant to provide an in-depth exploration of religion, but simply to introduce students to the anthropological approach to the study of religion. You should start with Wade Davis' TED Talk on The Worldwide Web of Belief and Ritual.

Definitions

There are various ways to define religion. One, the analytic definition stresses how religion manifests itself within a culture and identifies six dimensions of religion:

- Institutional: this refers to the organizational and leadership structure of religions; this may be complex with a bureaucracy or simple with only one leader

- Narrative: this refers to myths, e.g., creation stories

- Ritual: all religions have rites of passage and other activities

- Social: religions have social activities, perhaps beyond rituals, that helps to promote bonds between members

- Ethical: religions establish a moral code and approved behaviors for its members and even society at large

- Experiential: religious behavior is often focused on connection with a sacred reality beyond everyday experience

The functional definition highlights the role religion plays within a culture. This approach defines religion in terms of how it fulfills cognitive, emotional and social needs for its adherents.

The third definition looks at the essential nature of religion, hence its name, the essentialist definition. This approach defines religion as a system of beliefs and behaviors that characterizes the relationship between people and the supernatural. It is an adaptive behavior that promotes a sense of togetherness, unity and belonging. It helps to define one of the groups to which we belong. Warms (2008) takes an essentialist approach when he defines religion as a system that is composed of stories, includes rituals, has specialists, believes in the supernatural, and uses symbols and symbolism as well as altered states of consciousness. Additionally, Warms states that a key factor in religion is that it changes over time.

Let's look at these parts in more detail:

Religious systems have stories, or sacred narratives. Some stories may be more sacred than others, e.g., in Christianity the story of Christ's resurrection is more sacred then the story of Him turning water into wine at a wedding celebration. Stories may be about many things, but there are some common themes: origins of earth and humans, what happens when we die, deeds of important people, and disasters. Anthropologists can study these stories, or myths, to learn more about the people. Myth in anthropology should not be interpreted as a falsehood. In anthropology, a myth is a truism for the people following that belief system.

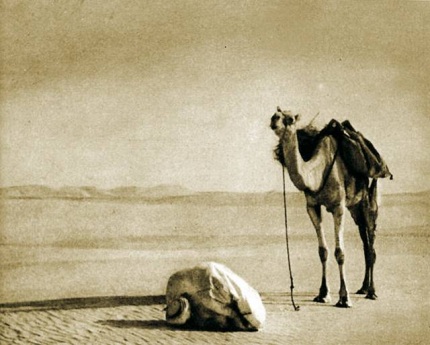

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)

An important part of religion is the belief in the supernatural, which includes a variety of beings from angels and demons to ghosts and gods and souls. The supernatural is a realm separate from the physical world inhabited by humans, although the supernatural can influence the human realm either through direct action or by influencing humans. For some peoples the supernatural realm is disconnected from everyday life; for others it is an intricate part of it. The supernatural can also refer to an unseen power that infuses humans, nature and for some belief systems, inanimate objects. Some groups refer to this power as mana, a term that is sometimes used to represent this supernatural power. This belief in a supernatural power is called animatism, while the belief in supernatural beings is animism.

Through rituals, people can influence or call upon the supernatural and supernatural power using symbolic action. Ritualsare standardized patterns of behavior; e.g., prayer, congregation, etc. In the realm of religion, rituals are a sacred practice. In some religions, rituals are highly stereotyped and deviation from the ritual results in either no influence on the supernatural or negative consequences. Nature based religions, particularly those led by shamans (see below) are not as wedded to the ritual and employ a degree of creativity when trying to influence the supernatural.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) - Diwali, Festival of Lights

Ritual promotes what Victor Turner called communitas, a sense of unity that transcends social distinctions like socioeconomic class. During the period of the ritual, rank and status are forgotten as members think of themselves as a community. This helps cement unity among community members.

Ritual can also be a portrayal Influence or a reenactment of myth, e.g., communion or baptism. Portrayal influence invokes magic to manipulate the supernatural. This has nothing to do with David Copperfield type of magic—it is about harnessing supernatural forces. If the magic does not seem to work, there is not a problem with the magic, but with the ritual—the practitioner did something wrong in their performance.

Magic uses a couple of principles: imitation (or similarity) and contagion. The principle of similarity states that if one acts out what one wants to happen then the likelihood of that occurring increases. Baptism is a good example of this as is the Pueblo Indians ritual of whipping yucca juice into frothy suds, which symbolize rain clouds. The principle of contagion states that things that been in contact with the supernatural remain connected to the supernatural. That connection can be used to transfer mana from the one thing to the other. Voodoo dolls are the classic example of the law of contagion, however, some cultures belief that names also have mana, so for anyone outside of the family to know their real name gives them the power to perform black magic against them.

Another form of magic is divination. Divination is the use of ritual to obtain answers to questions from supernatural sources, e.g., oracle bones, tea leaves, way a person falls, date of birth, etc. There are two main categories of divination: those results that can be influenced by diviner and those that cannot. Tarot cards, tea leaves, randomly selecting a Bible verse and interpreting an astrological sign are examples of the former. Casting lots, flipping a coin or checking to see whether something floats on water are examples of the latter.

Ritual is infused with symbolic expression. Emile Durkheim suggested that religious systems were a set of practices related to sacred things. The sacred is that which inspires awe, respect and reverence because it is set apart from the secular world or is forbidden. People create symbols to represent aspects of society that inspire these feelings. For instance, the totems of Australian aborigine groups is spiritually related to members of the society. The human soul is a kindred spirit to the sacred plant or animal. Clifford Geertz discussed how symbols expressed feelings of society to maintain stability. This approach helped to broaden early definitions of religion beyond supernatural to incorporate actions of people and helped to account for the deep commitment and behavior of adherents.

There are several types of religious practitioners or people who specialize in religious behaviors. These are individuals who specialize in the use of spiritual power to influence others. A shaman is an

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) - Buddhist monks

individual who has access to supernatural power that can then be used for the benefit of specific clients. Found in indigenous cultures, shamans may be part-time specialists, but is usually the only person in the group that can access the supernatural. They have specialized knowledge that is deemed too dangerous for everyone to know because they do not have the training to handle the knowledge. Oftentimes, shamans train their replacement in the ways of contacting and utilizing the supernatural. Shamans are often innovative in their practices, using trance states to contact the supernatural.

The term shaman originated with the Tungus peoples of eastern Siberia. Anthropologists debate the ethics of using the term to apply to all indigenous religious practitioners. Some think that we should use each cultures' name for their religious practitioners; others take the position that use of the term is not meant to be disrespectful but is simply a way for all anthropologists to categorize a cultural trait much like we use the names of several cultures for the anthropological kinship terminology systems. There is also public debate about the increasing number of so-called white shamans, especially in the United States where there is still heated debate about the plight of Native Americans. For more information on this debate, check out the video White Shamans and Plastic Medicine Men on YouTube.

Priests are another type of religious practitioner who are trained to perform rituals for benefit of group. Priests differ from shamans is a couple of important ways. For priests, rituals are key—innovation and creativity are generally not prized or encouraged. Priests are found in most organized religions, e.g., Buddhism, Christianity and Judaism, although they have a different name such as monks, ministers, or rabbis.

Sorcerers and witches, unlike shamans and priests who have high status in their cultures, usually have low status because their abilities are seen in a negative manner. Both sorcerers and witches have the ability to connect with the supernatural for ill purposes. Sorcerers often take on a role similar to law enforcement in the United States; they are used by people to punish someone who has violated socially proscribed rules. Witches are believed to have an innate connection to the supernatural, one that they often cannot control. Because witches may inadvertently hurt people because they cannot control their power, if discovered, they are often ostracized or forced to leave their group. It is important to differentiate witches in some cultures from Wiccans. While Christianity makes no distinction between Wiccans and witches as described above, Wicca has clear mandates against using magic to harm others. The Wiccan rede states, “An' it harm none, do what ye will.”

Mediums are part-time practitioners who use trance and possession to heal and divine. Oftentimes after a trance or possession, the medium remembers nothing about the experience or their actions.

Anthropologists have identified a pattern linking the type and number of practitioners with social complexity: the more complex the society, the more variety of religious practitioners. Foraging cultures tend to have only one practitioner, a shaman. If a culture has two practitioners, a shaman and a priest, chances are that they are agriculturalists, albeit without complex political and social organization. Agriculturalists and pastoralists with more complex political organization that goes beyond the immediate community, generally have a least three types of practitioners, shamans, priests and a sorcerer, witch or medium. Cultures with complex political organization, agriculture, and complex social organization usually have all four practitioners (Bonvillain 2010).