2.2: Theory of Verbal Communication- Important Concepts

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 75153

- Manon Allard-Kropp

- University of Missouri–St. Louis

2.2 Theory of Verbal Communication: Important Concepts

“Consciousness can’t evolve any faster than language.” —Terence McKenna

Imagine for a moment that you have no language with which to communicate. It’s hard to imagine, isn’t it? It’s probably even harder to imagine that with all of the advancements we have at our disposal today, there are people in our world who actually do not have, or cannot use, language to communicate.

2.2.1 Sign Language

Nearly 25 years ago, the Nicaraguan government started bringing deaf children together from all over the country in an attempt to educate them. These children had spent their lives in remote places and had no contact with other deaf people. They had never learned a language and could not understand their teachers or each other. Likewise, their teachers could not understand them. Shortly after bringing these students together, the teachers noticed that the students communicated with each other in what appeared to be an organized fashion: they had literally brought together the individual gestures they used at home and composed them into a new language. Although the teachers still did not understand what the kids were saying, they were astonished at what they were witnessing—the birth of a new language in the late 20th century! This was an unprecedented discovery.

In 1986, American linguist Judy Kegl went to Nicaragua to find out what she could learn from these children without language. She contends that our brains are open to language until the age of 12 or 13, and then language becomes difficult to learn. She quickly discovered approximately 300 people in Nicaragua who did not have language and says, “They are invaluable to research—among the only people on Earth who can provide clues to the beginnings of human communication.” To access the full transcript, view the following link:

Supplemental reading: CBS News: Birth of a Language

Adrien Perez, one of the early deaf students who formed this new language (referred to as Nicaraguan Sign Language), says that without verbal communication, “You can’t express your feelings. Your thoughts may be there but you can’t get them out. And you can’t get new thoughts in.”

As one of the few people on earth who has experienced life with and without verbal communication, his comments speak to the heart of communication: it is the essence of who we are and how we understand our world. We use it to form our identities, initiate and maintain relationships, express our needs and wants, construct and shape world-views, and achieve personal goals (Pelley).

2.2.2 Defining Verbal Communication

When people ponder the word communication, they often think about the act of talking. We rely on verbal communication to exchange messages with one another and develop as individuals. The term verbal communication often evokes the idea of spoken communication, but written communication is also part of verbal communication. Reading this book, you are decoding the authors’ written verbal communication in order to learn more about communication. Let’s explore the various components of our definition of verbal communication and examine how it functions in our lives.

| Verbal Communication | Nonverbal Communication | |

| Oral | Spoken language | Laughing, crying, coughing, etc. |

| Non oral | Written language/sign language | Gestures, body language, etc. |

Verbal communication is about language, both written and spoken. In general, verbal communication refers to our use of words, whereas nonverbal communication refers to communication that occurs through means other than words, such as body language, gestures, and silence. Both verbal and nonverbal communication can be spoken and written. Many people mistakenly assume that verbal communication refers only to spoken communication. However, you will learn that this is not the case. Let’s say you tell a friend a joke, and he or she laughs in response. Is the laughter verbal or nonverbal communication? Why? As laughter is not a word, we would consider this vocal act as a form of nonverbal communication. For simplification, the table above highlights the kinds of communication that fall into the various categories. You can find many definitions of verbal communication in our literature, but for this text, we define verbal communication as an agreed-upon and rule-governed system of symbols used to share meaning. Let’s examine each component of this definition in detail.

A System of Symbols

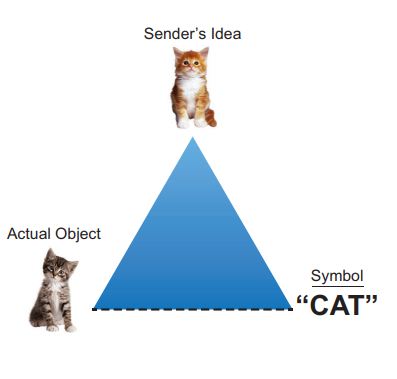

Symbols are arbitrary representations of thoughts, ideas, emotions, objects, or actions used to encode and decode meaning (Nelson & Kessler Shaw). Symbols stand for, or represent, something else. For example, there is nothing inherent about calling a cat a cat.

Rather, English speakers have agreed that these symbols (words), whose components (letters) are used in a particular order each time, stand for both the actual object, as well as our interpretation of that object. This idea is illustrated by C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richard’s triangle of meaning. The word “cat” is not the actual cat. Nor does it have any direct connection to an actual cat. Instead, it is a symbolic representation of our idea of a cat, as indicated by the line going from the word “cat” to the speaker’s idea of “cat” to the actual object.

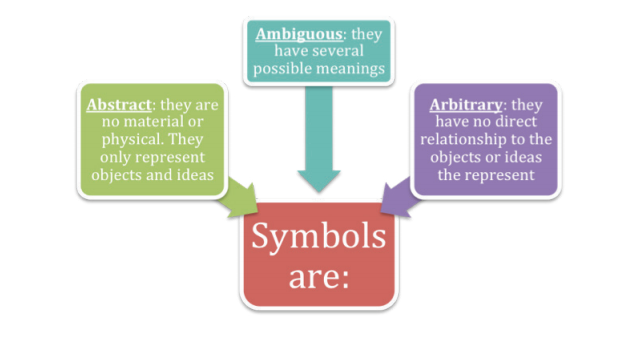

Symbols have three distinct qualities: they are arbitrary, ambiguous, and abstract. Notice that the picture of the cat on the left side of the triangle more closely represents a real cat than the word “cat.” However, we do not use pictures as language, or verbal communication. Instead, we use words to represent our ideas. This example demonstrates our agreement that the word “cat” represents or stands for a real cat AND our idea of a cat. The symbols we use are arbitrary and have no direct relationship to the objects or ideas they represent. We generally consider communication successful when we reach agreement on the meanings of the symbols we use (Duck).

Symbols Are Abstract, Ambiguous, Arbitrary

Not only are symbols arbitrary, they are ambiguous—that is, they have several possible meanings. Imagine your friend tells you she has an apple on her desk. Is she referring to a piece of fruit or her computer? If a friend says that a person he met is cool, does he mean that person is cold or awesome? The meanings of symbols change over time due to changes in social norms, values, and advances in technology. You might be asking, “If symbols can have multiple meanings then how do we communicate and understand one another?” We are able to communicate because there are a finite number of possible meanings for our symbols, a range of meanings which the members of a given language system agree upon. Without an agreed-upon system of symbols, we could share relatively little meaning with one another.

A simple example of ambiguity can be represented by one of your classmates asking a simple question to the teacher during a lecture where she is showing PowerPoint slides: “Can you go to the last slide, please?” The teacher is halfway through the presentation. Is the student asking if the teacher can go back to the previous slide? Or does the student really want the lecture to be over with and is insisting that the teacher jump to the final slide of the presentation? Chances are the student missed a point on the previous slide and would like to see it again to quickly take notes. However, suspense may have overtaken the student and they may have a desire to see the final slide. Even a simple word like “last” can be ambiguous and open to more than one interpretation.

The verbal symbols we use are also abstract, meaning that words are not material or physical. A certain level of abstraction is inherent in the fact that symbols can only represent objects and ideas. This abstraction allows us to use a phrase like “the public” in a broad way to mean all the people in the United States rather than having to distinguish among all the diverse groups that make up the U.S. population. Similarly, in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter book series, wizards and witches call the non-magical population on earth “muggles” rather than having to define all the separate cultures of muggles. Abstraction is helpful when you want to communicate complex concepts in a simple way. However, the more abstract the language, the greater potential there is for confusion.

Rule-Governed

Verbal communication is rule-governed. We must follow agreed-upon rules to make sense of the symbols we share. Let’s take another look at our example of the word cat. What would happen if there were no rules for using the symbols (letters) that make up this word? If placing these symbols in a proper order was not important, then cta, tac, tca, act, or atc could all mean cat. Even worse, what if you could use any three letters to refer to cat? Or still worse, what if there were no rules and anything could represent cat? Clearly, it’s important that we have rules to govern our verbal communication. There are four general rules for verbal communication, involving the sounds, meaning, arrangement, and use of symbols.

- Phonology is the study of speech sounds. The pronunciation of the word cat comes from the rules governing how letters sound, especially in relation to one another. The context in which words are spoken may provide answers for how they should be pronounced. When we don’t follow phonological rules, confusion results. One way to understand and apply phonological rules is to use syntactic and pragmatic rules to clarify phonological rules.

- Semantic rules help us understand the difference in meaning between the word cat and the word dog. Instead of each of these words meaning any four-legged domestic pet, we use each word to specify what four-legged domestic pet we are talking about. You’ve probably used these words to say things like, “I’m a cat person” or “I’m a dog person.” Each of these statements provides insight into what the sender is trying to communicate. We attach meanings to words; meanings are not inherent in words themselves. As you’ve been reading, words (symbols) are arbitrary and attain meaning only when people give them meaning. While we can always look to a dictionary to find a standardized definition of a word, or its denotative meaning, meanings do not always follow standard, agreed upon definitions when used in various contexts. For example, think of the word “sick.” The denotative definition of the word is ill or unwell. However, connotative meanings, the meanings we assign based on our experiences and beliefs, are quite varied. Sick can have a connotative meaning that describes something as good or awesome as opposed to its literal meaning of illness, which usually has a negative association. The denotative and connotative definitions of “sick” are in total contrast of one another, which can cause confusion. Think about an instance where a student is asked by their parent about a friend at school. The student replies that the friend is “sick.” The parent then asks about the new teacher at school and the student describes the teacher as “sick” as well. The parent must now ask for clarification as they do not know if the teacher is in bad health, or is an excellent teacher, and if the friend of their child is ill or awesome.

- Syntactics is the study of language structure and symbolic arrangement. Syntactics focuses on the rules we use to combine words into meaningful sentences and statements. We speak and write according to agreed-upon syntactic rules to keep meaning coherent and understandable. Think about this sentence: “The pink and purple elephant flapped its wings and flew out the window.” While the content of this sentence is fictitious and unreal, you can understand and visualize it because it follows syntactic rules for language structure.

- Pragmatics is the study of how people actually use verbal communication. For example, as a student you probably speak more formally to your professors than to your peers. It’s likely that you make different word choices when you speak to your parents than you do when you speak to your friends. Think of the words “bowel movements,” “poop,” “crap,” and “shit.” While all of these words have essentially the same denotative meaning, people make choices based on context and audience regarding which word they feel comfortable using. These differences illustrate the pragmatics of our verbal communication. Even though you use agreed-upon symbolic systems and follow phonological, syntactic, and semantic rules, you apply these rules differently in different contexts. Each communication context has different rules for “appropriate” communication. We are trained from a young age to communicate “appropriately” in different social contexts.

It is only through an agreed-upon and rule-governed system of symbols that we can exchange verbal communication in an effective manner. Without agreement, rules, and symbols, verbal communication would not work. The reality is, after we learn language in school, we don’t spend much time consciously thinking about all of these rules, we simply use them. However, rules keep our verbal communication structured in ways that make it useful for us to communicate more effectively.

2.2 Adapted from Survey of Communication Study (Laura K. Hahn & Scott T. Paynton, 2019)

2.2.3 Mental Grammar and Phonology

You can either watch the video at the following link, or read the script below.

Watch the video: Mental Grammar (Anderson, 2018)

Video transcript:

We know now that linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It’s also important to know that linguistics is one member of the broad field that’s known as cognitive science. The cognitive sciences are interested in what goes on in the mind, and in linguistics we’re specifically interested in how our language knowledge is represented and organized in the human mind.

Think about this: you and I both speak English. I’m speaking English right here on this video, and you’re listening and understanding me. Right now, I’ve got some idea in my mind that I want to express. I’m squeezing air out of my lungs, I’m vibrating my vocal folds, I’m manipulating parts of my mouth to produce sounds. Those sounds are captured by a microphone and now they’re playing on your computer. In response to the sound coming from your computer speaker or your headphones, your eardrums are vibrating and sending signals to your brain with the result that the idea in your mind is something similar to the idea that was in my mind when I made this video. There must be something that your mind and my mind have in common to allow that to happen, some shared system that allows us to understand each other, to understand each other’s ideas when we speak.

In linguistics, we call that system the mental grammar and our primary goal is to find out what that shared system is like. All speakers of all languages have a mental grammar, that shared system that lets speakers of a language understand each other. In essentials of linguistics, we devote most of our attention to the mental grammar of English, but we’ll also use our scientific tools and techniques to examine some parts of the grammars of other languages.

We’ll start by looking at sound systems, how speakers make particular sounds and how listeners hear these sounds. If you’ve ever tried to learn a second language, you know that the sounds in the second language are not always the same as in your first language. Linguists call the study of speech sounds phonetics. Then we’ll look at how the mental grammar of each language organizes sounds the mind. This is called phonology. We’ll examine the strategies that languages use to form meaningful words. This is called morphology. Then we take a close look at the different ways that languages combine words to form phrases and sentences. The term for that is syntax. We also look at how the meanings of words and sentences are organized in the mind, which linguists call semantics.

These five things are the core pieces of the mental grammar of any language. They’re the things all speakers know about their language. All languages have phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics in their grammars. And these five areas are also the core subfields of theoretical linguistics. Just as there are other kinds of language knowledge we have there are other branches of the field of linguistics, and we’ll take a peek at some of those other branches along the way.

We will study each of these aspects of linguistics study more in depth over the next few checkpoints.

2.2.4 Sounds and Language, Language and Sounds

Phonology

Phonology is the use of sounds to encode messages within a spoken human language. Babies are born with the capacity to speak any language because they can make sounds and hear differences in sounds that adults would not be able to do. This is what parents hear as baby talk. The infant is trying out all of the different sounds they can produce. As the infant begins to learn the language from their parents, they begin to narrow the range of sounds they produce to ones common to the language they are learning, and by the age of 5, they no longer have the vocal range they had previously. For example, a common sound that is used in Indian language is /dh/. To any native Indian there is a huge difference between /dh/ and /d/, but for people like me who cannot speak Hindi, not only can we not hear the difference, but it is very difficult to even attempt to produce this sound. Another large variation between languages for phonology is where in your mouth you speak from. In English, we speak mostly from the front or middle of our mouths, but it is very common in African languages to speak from the glottal, which is the deepest part of one’s throat.

The Biological Basis of Language

The human anatomy that allowed the development of language emerged six to seven million years ago when the first human ancestors became bipedal—habitually walking on two feet. Most other mammals are quadrupedal—they move about on four feet. This evolutionary development freed up the forelimbs of human ancestors for other activities, such as carrying items and doing more and more complex things with their hands. It also started a chain of anatomical adaptations. One adaptation was a change in the way the skull was placed on the spine. The skull of quadrupedal animals is attached to the spine at the back of the skull because the head is thrust forward. With the new upright bipedal position of pre-humans, the attachment to the spine moved toward the center of the base of the skull. This skeletal change in turn brought about changes in the shape and position of the mouth and throat anatomy.

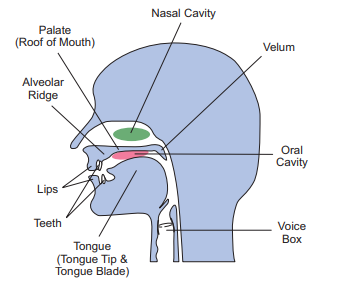

Humans have all the same organs in the mouth and throat that the other great apes have, but the larynx, or voice box (you may know it as the Adam’s apple), is in a lower position in the throat in humans. This creates a longer pharynx, or throat cavity, which functions as a resonating and amplifying chamber for the speech sounds emitted by the larynx. The rounding of the shape of the tongue and palate, or the roof of the mouth, enables humans to make a greater variety of sounds than any great ape is capable of making (see Figure 2.5).

Speech is produced by exhaling air from the lungs, which passes through the larynx. The voice is created by the vibration of the vocal folds in the larynx when they are pulled tightly together, leaving a narrow slit for the air to pass through under pressure. The narrower the slit, the higher the pitch of the sound produced. The sound waves in the exhaled air pass through the pharynx then out through the mouth and/or the nose. The different positions and movements of the articulators—the tongue, the lips, the jaw— produce the different speech sounds.

Along with the changes in mouth and throat anatomy that made speech possible came a gradual enlargement and compartmentalization of the brain of human ancestors over millions of years. The modern human brain is among the largest, in proportion to body size, of all animals. This development was crucial to language ability because a tremendous amount of brain power is required to process, store, produce, and comprehend the complex system of any human language and its associated culture. In addition, two areas in the left brain are specifically dedicated to the processing of language; no other species has them. They are Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe near the temple, and Wernicke’s area, in the temporal lobe just behind the left ear.

Paralanguage

Paralanguage refers to those characteristics of speech beyond the actual words spoken. These include the features that are inherent to all speech: pitch, loudness, and tempo or duration of the sounds. Varying pitch can convey any number of messages: a question, sarcasm, defiance, surprise, confidence or lack of it, impatience, and many other often subtle connotations. An utterance that is shouted at close range usually conveys an emotional element, such as anger or urgency. A word or syllable that is held for an undue amount of time can intensify the impact of that word. For example, compare “It’s beautiful” versus “It’s beauuuuu-tiful!” Often the latter type of expression is further emphasized by extra loudness of the syllable, and perhaps higher pitch; all can serve to make a part of the utterance more important. Other paralinguistic features that often accompany speech might be a chuckle, a sigh or sob, deliberate throat clearing, and many other non-verbal sounds like “hm,” “oh,” “ah,” and “um.”

Most non-verbal behaviors are unconsciously performed and not noticed unless someone violates the cultural standards for them. In fact, a deliberate violation itself can convey meaning. Other non-verbal behaviors are done consciously like the U.S. gestures that indicate approval, such as thumbs up, or making a circle with your thumb and forefinger—“OK.” Other examples are waving at someone or putting a forefinger to your lips to quiet another person. Many of these deliberate gestures have different meanings (or no meaning at all) in other cultures. For example, the gestures of approval in U.S. culture mentioned above may be obscene or negative gestures in another culture.

Try this: As an experiment in the power of non-verbal communication, try violating one of the cultural rules for proxemics or eye contact with a person you know. Choosing your “guinea pigs” carefully (they might get mad at you!), try standing or sitting a little closer or farther away from them than you usually would for a period of time, until they notice (and they will notice). Or, you could choose to give them a bit too much eye contact, or too little, while you are conversing with them. Note how they react to your behavior and how long it takes them to notice.

Phonemes

A phoneme is the smallest phonetic unit in a language that is capable of conveying a distinction in meaning. For example, in English we can tell that pail and tail are different words, so /p/ and /t/ are phonemes. Two words differing in only one sound, like pail and tail, are called a minimal pair. The International Phonetic Association created the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), a collection of standardized representations of the sounds of spoken language.

When a native speaker does not recognize different sounds as being distinct they are called allophones. For example, in the English language we consider the p in pin and the p in spin to have the same phoneme, which makes them allophones. In Chinese, however, these two similar phonemes are treated separately and both have a separate symbol in their alphabet. The minimum bits of meaning that native speakers recognize are known as phonemes. It is any small set of units, usually about 20 to 60 in number, and different for each language, considered to be the basic distinctive units of speech sound by which morphemes, words, and sentences are represented.

A phoneme is defined as the minimal unit of sound that can make a difference in meaning if substituted for another sound in a word that is otherwise identical. The phoneme itself does not carry meaning. For example, in English if the sound we associate with the letter “p” is substituted for the sound of the letter “b” in the word bit, the word’s meaning is changed because now it is pit, a different word with an entirely different meaning. The human articulatory anatomy is capable of producing many hundreds of sounds, but no language has more than about 100 phonemes. English has about 36 or 37 phonemes, including about eleven vowels, depending on dialect. Hawaiian has only five vowels and about eight consonants. No two languages have the same exact set of phonemes.

Linguists use a written system called the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to represent the sounds of a language. Unlike the letters of our alphabet that spell English words, each IPA symbol always represents only one sound no matter the language. For example, the letter “a” in English can represent the different vowel sounds in such words as cat, make, papa, law, etc., but the IPA symbol /a/ always and only represents the vowel sound of papa or pop.

2.2.4 Adapted from Cultural Anthropology, Communication and Language (Wikibooks contributors, 2018) Adapted from Perspectives, Language (Linda Light, 2017)

2.2.5 Morphology, Syntax, and Semantics

The study of the structures of language is called descriptive linguistics. Descriptive linguists discover and describe the phonemes of a language, research called phonology. They study the lexicon (the vocabulary) of a language and how the morphemes are used to create new words, or morphology. They analyze the rules by which speakers create phrases and sentences, or the study of syntax. And they look at how these features all combine to convey meaning in certain social contexts, fields of study called semantics and pragmatics.

Morphology

The definition of morphology is the study of the structure of words formed together, or more simply put, the study of morphemes. Morphemes are the smallest utterances with meaning. Not all morphemes are words. Many languages use affixes, which carry specific grammatical meanings and are therefore morphemes, but are not words. For example, English-speakers do not think of the suffix -ing as a word, but it is a morpheme. The creation of morphemes rather than words also allowed anthropologists to more easily translate languages. For example, in the English language, the prefix un- means “the opposite, not, or lacking,” which can distinguish the words “unheard” and “heard” apart from each other.

Morphology is very helpful in translating different languages, such as the language Bangla. For example, some words do not have a literal translation from Bangla to English because a word in Bangla may mean more than one word in English. Two professors from Bangladesh discovered an algorithm that could translate Bangla words, as they are generally very complex. They first search for the whole word. If this does not come up with results, they then search the first morpheme they find; in one example, it was “Ma” of “Manushtir.” “Ma” was a correct morpheme, however “nushtir” was not. The researchers then attempted “Man,” however “ushtir” was not a correct morpheme. They next tried “Manush” and “tir,” discovering that this was correct combination of morphemes.

The Units That Carry Meaning: Morphemes

Morphemes are “the smallest grammatical unit of language” that has semantic meaning. In spoken language, morphemes are composed of phonemes (the smallest unit of spoken language), but in written language morphemes are composed of graphemes (the smallest unit of written language). A morpheme can stand alone, meaning it forms a word by itself, or be a bound morpheme, where it has to attach to another bound morpheme or a standalone morpheme in order to form a word. Prefixes and suffixes are the simplest form of bound morphemes. For example, the word “bookkeeper” has three morphemes: “book,” “keep,” and “-er.” This example illustrates the key difference between a word and a morpheme; although a morpheme can be a standalone word, it can also need to be associated with other units in order to make sense. Meaning that one would not go around saying “-er” interdependently, it must be bound to one or more other morphemes.

A morpheme is a minimal unit of meaning in a language; a morpheme cannot be broken down into any smaller units that still relate to the original meaning. It may be a word that can stand alone, called an unbound morpheme (dog, happy, go, educate). Or it could be any part of a word that carries meaning that cannot stand alone but must be attached to another morpheme, bound morphemes. They may be placed at the beginning of the root word, such as un- (“not,” as in unhappy), or re- (“again,” as in rearrange). Or, they may follow the root, as in -ly (makes an adjective into an adverb: quickly from quick), -s (for plural, possessive, or a verb ending) in English. Some languages, like Chinese, have very few if any bound morphemes. Others, like Swahili have so many that nouns and verbs cannot stand alone as separate words; they must have one or more other bound morphemes attached to them.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning. Some anthropologists have seen linguistics as basic to a science of man because it provides a link between the biological and sociocultural levels. Modern linguistics is diffusing widely in anthropology itself among younger scholars, producing work of competence that ranges from historical and descriptive studies to problems of semantic and social variation. In the 1960s, Chomsky prompted a formal analysis of semantics and argued that grammars needed to represent all of a speaker’s linguistic knowledge, including the meaning of words. Most semanticists focused attention on how words are linked to each other within a language through five different relations:

1. Synonymy—same meaning (ex: old and aged)

2. Homophony—same sound, different meaning (ex: would and wood)

3. Antonymy—opposite meaning (ex: tall and short)

4. Denotation—what words refer to in the “real” world (ex: having the word pig refer to the actual animal, instead of pig meaning dirty, smelly, messy, or sloppy)

5. Connotation—additional meanings that derive from the typical contexts in which they are used in everyday speech (ex: calling a person a pig, not meaning the animal but meaning that they are dirty, smelly, messy, or sloppy)

Formal semanticists only focused on the first four, but we have now discovered that our ability to use the same words in different ways (and different words in the same way) goes beyond the limits of formal semantics. Included in the study of semantics are metaphors, which are a form of figurative or nonliteral language that links together expressions from unrelated semantic domains. A semantic domain is a set of linguistic expressions with interrelated meanings; for example, the words pig and chicken are in the same semantic domain. But when you use a metaphor to call a police officer a pig, you are combining two semantic domains to create meaning that the police officer is fat, greedy, dirty, etc.

Conveying Meaning in Language: Semantics and Pragmatics

The whole purpose of language is to communicate meaning about the world around us so the study of meaning is of great interest to linguists and anthropologists alike. The field of semantics focuses on the study of the meanings of words and other morphemes as well as how the meanings of phrases and sentences derive from them. Recently linguists have been enjoying examining the multitude of meanings and uses of the word “like” among American youth, made famous through the film Valley Girl in 1983. Although it started as a feature of California English, it has spread all across the country, and even to many young second-language speakers of English. It’s, like, totally awesome dude!

The study of pragmatics looks at the social and cultural aspects of meaning and how the context of an interaction affects it. One aspect of pragmatics is the speech act. Any time we speak we are performing an act, but what we are actually trying to accomplish with that utterance may not be interpretable through the dictionary meanings of the words themselves. For example, if you are at the dinner table and say, “Can you pass the salt?” you are probably not asking if the other person is capable of giving you the salt. Often the more polite an utterance, the less direct it will be syntactically. For example, rather than using the imperative syntactic form and saying “Give me a cup of coffee,” it is considered more polite to use the question form and say “Would you please give me a cup of coffee?”

The Structure of Phrases and Sentences: Syntax

Rules of syntax tell the speaker how to put morphemes together grammatically and meaningfully. There are two main types of syntactic rules: rules that govern word order, and rules that direct the use of certain morphemes that perform a grammatical function. For example, the order of words in the English sentence “The cat chased the dog” cannot be changed around or its meaning would change: “The dog chased the cat” (something entirely different) or “Dog cat the chased the” (something meaningless). English relies on word order much more than many other languages do because it has so few morphemes that can do the same type of work.

For example, in our sentence above, the phrase “the cat” must go first in the sentence, because that is how English indicates the subject of the sentence, the one that does the action of the verb. The phrase “the dog” must go after the verb, indicating that it is the dog that received the action of the verb, or is its object. Other syntactic rules tell us that we must put “the” before its noun, and “-ed” at the end of the verb to indicate past tense. In Russian, the same sentence has fewer restrictions on word order because it has bound morphemes that are attached to the nouns to indicate which one is the subject and which is the object of the verb. So the sentence koshka [chased] sobaku, which means “the cat chased the dog,” has the same meaning no matter how we order the words, because the -a on the end of koshka means the cat is the subject, and the -u on the end of sobaku means the dog is the object. If we switched the endings and said koshku [chased] sobaka, now it means the dog did the chasing, even though we haven’t changed the order of the words. Notice, too, that Russian does not have a word for “the.”

Syntax is the study of rules and principles for constructing sentences in natural languages. Syntax studies the patterns of forming sentences and phrases as well. It comes from ancient Greek (“syn-” means together and “taxis” means arrangement.) Outside of linguistics, syntax is also used to refer to the rules of mathematical systems, such as logic, artificial formal languages, and computer programming language. There are many theoretical approaches to the study of syntax. Noam Chomsky, a linguist, sees syntax as a branch of biology, since they view syntax as the study of linguistic knowledge as the human mind sees it. Other linguists take a Platonistic view, in that they regard syntax to be the study of an abstract formal system.

Major Approaches to Syntax

Generative grammar: Noam Chomsky pioneered the generative approach to syntax. The hypothesis is that syntax is a structure of the human mind. The goal is to make a complete model of this inner language, and the model could be used to describe all human language and to predict if any utterance would sound correct to a native speaker of the language. It focuses mostly on the form of the sentence rather than the communicative function of it. The majority of generative theories assume that syntax is based on the constituent structure of sentences.

Categorial grammar: An approach that attributes the syntactic structure to the properties of the syntactic categories, rather than to the rules of grammar.

Dependency grammar: Structure is determined by the relations between a word and its dependents rather than being based on constituent structure.

2.2.5 Adapted from Cultural Anthropology, Communication and Language (Wikibooks contributors, 2018)