1.6: Listening

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 79235

Listening and Compassionate Listening

If we can change ourselves, we can change the world…This is the essence of compassionate listening: seeing the person next to you as part of yourself…As the Compassionate Listening Project has pointed out, when you approach a moment without judgment and can connect with the sacredness of the agency of each soul, we can transform the moment…[and] evolve.

~ Rep. Dennis Kucinich (Hoffman, 2013, p.317)

Chapter Overview

Not knowing how to listen, neither can they speak. ~ Heraclitus

Creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com

Listening seems like an automatic process. However, though it is a process, it is far from automatic or obvious. This chapter will define listening and distinguish different skills for improving one’s intercultural communication.

Listening Defined

“Listening is the learned process of receiving, interpreting, recalling, evaluating, and responding to verbal and nonverbal messages” (Communication, 2016, p.230). Listening is a choice whereas hearing is a physiological action. Further, listening is a skill one can cultivate. Notice, though, that the interpretation of how, and hence whether, you are listening may be seen through a cultural lens. For example, giving eye contact in an American context would be seen as direct – but not a “stare down.” Yet, direct gazes in many cultures are seen as inappropriate. The ability to observe and adapt to the communication partner will be useful in an intercultural communication conversation or interview. Consider the many questions going through one’s head: “Is my partner looking down–maybe I should look away?” “Is this person giving me, the stare down?” Listening skills take time to cultivate and interpretation of the message, is tough. Learning the skills of active and compassionate listening, though, assists one in developing intercultural communication competence.

The Process of Listening

Intercultural communication, like all communication, seeks to share and understand meaning in diverse settings. Below, Green, Keith Green, Fairchild, Knudsen & Lease-Gubrud (2018) explain the process of listening in the materials accessed from their creative commons OER book, Introduction to Communication: A Free, Open-Source, Introductory Communication Studies Text:

Human relationships are built on communication. As we speak and listen, learn about each other, and get to know each other in personal ways, relationships grow and thrive. Our relationships are defined by how we communicate, including what we talk about, when we talk about it, and how we respond. The substance of relationships is how we communicate. Interaction is comprised of what we tell each other (disclosure) and how we attend to each other’s disclosure (listening).

(Green, Fairchild, Knudsen & Lease-Gubrud, 2018 – Image 1)

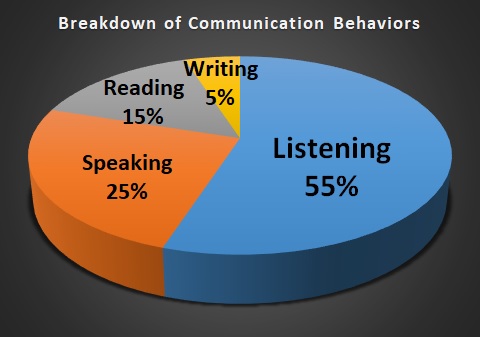

We engage in four communication behaviors: listening, speaking, reading and writing. Of these four, listening is by far the most frequently used. According to the International Listening Association, ‘Listening is the process of receiving, constructing meaning from, and responding to spoken and/or nonverbal messages’ (Verderber and MacGeorge, p.197).

Ever since the first major study to assess listening time, the Rankin study of 1926, researchers have looked at how we use each of these behaviors within our overall communication package (Brownell, 2010). Taking into account a range of studies since Rankin, we can estimate the breakdown of our communication behaviors as shown in Image 1. The specific distribution of our individual communication behaviors will change daily and according to variables such as jobs, interests, and activities.

An interesting contrast is the time we spend on learning each of these behaviors which is directly inverted to the time we spend on each. From kindergarten to college we take classes on improving writing ability. We are taught how to read well into high school. High school students spend significantly less time learning public speaking than they do reading and writing. Listening, which is the most commonly used communication behavior, is rarely taught as a unique, identifiable skill.

Listening is the most relational of all our communication behaviors. How we listen to another affects our relationships more than anything else we do. Too often we focus on what to say, when in actuality we need to focus far more on just listening to what the other person is saying. When others focus on us, attending to what we have to say, and really listening and understanding our concerns, they are giving us a powerful message of worth and value (Green, Fairchild, Knudsen & Lease-Gubrud, 2018, Module 5, Section 1).

Active Listening

LISTEN: Halverson-Wente photograph, used with permission

“Active listening refers to the process of pairing outwardly visible positive listening behaviors with positive cognitive listening practices. Active listening can help address many of the environmental, physical, cognitive, and personal barriers to effective listening… The behaviors associated with active listening can also enhance informational, critical, and empathetic listening” (Communication, 2016).

Some basic skills related to active listening include:

- Use of “I” statements to show the speaker that any reflection is “yours” and, as such, an interpretation.

- Nonverbally, active listeners try to, “SOFTEN” the communication situation to show nonverbally that one is listening. SOFTEN refers to the use of a Smile, Open Posture, Facial Expressions, Touch (by shaking hands or another appropriate manner), Eye Contact, Nods (Wassmer, 1978).

- Reply with a paraphrase (or restatement in your own words) to show one is listening and to clarify the message.

These three areas tend to be traditional skills when discussing active listening. However, some scholars in “Compassion Studies” stress the need to just listen without stopping the conversation or redirecting it.

Creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com

Listening is part of the third component of intercultural communication competence–the other two competencies being motivation (motivated to do what is necessary for a successful intercultural communication encounter) and possessing a certain level of knowledge about other cultures (Samovar, Porter, McDaniel, & Roy, 2017; Lustig and Koestler, 2010). Though listed under the component of skills, the practice of which make intercultural communication encounters more successful, listening is certainly part of all three components of intercultural communication competence. Keep in mind, though, that culture affects listening. For example, different cultures put different values on listening in their communication process. Many Asian cultures hold that words may clutter one’s understanding; silence, then, is often valued over talking–consider the Buddhist expression, “There is a truth that words cannot reach.”

Active Listening Tips for Intercultural Communication Situations

Rochester Diversity Council photo, used with permission

Listening is active and is part and parcel of effective and sensitive perception checking that moves the conversation forward and demonstrates effective intercultural communication competence. While remembering each culture possesses unique communication norms, expectations, and behaviors, McLean (2018) shares some general tips to facilitate active listening and reading:

- Maintain eye contact with the speaker when culturally appropriate.

- Don’t interrupt.

- Focus your attention on the message and how it is said, not your internal monologue.

- Restate the message in your own words and ask if you understood correctly.

- Ask clarifying questions to communicate interest and gain insight

(McLean, 2018, Section 2.6).

Compassionate Listening

The concept of compassionate listening (in the literature, akin to mindfulness or empathy), it is argued, is a particularly effective listening posture–a touchstone for effective intercultural communication that enables one to respectfully communicate and learn with a profound richness and depth in an intercultural/diverse setting. Compassionate listening sometimes is called, “empathic” listening. However, compassionate listening is much more than showing empathy.

Creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com

Empathy is a gateway to compassion. It’s understanding how someone feels, and trying to imagine how that might feel for you — it’s a mode of relating. Compassion takes it further. It’s feeling what that person is feeling, holding it, accepting it, and taking some kind of action. In metta or loving-kindness meditation practice, one can silently repeat phrases to others as a way of acknowledging them and our own interconnectedness. It’s easy and highly portable. When I’m on the train, I silently repeat phrases like, “May you be happy; may you be safe; may you be at ease; may you be free from suffering,” to the passengers, particularly those who look like they need it most. This plants the seeds of compassion, and we can find ourselves acting in compassionate ways that never would have occurred to us before. As it turns out, this ancient practice has some amazing scientific discoveries to give it cred (Chandler, n.d.).

Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk and Noel Peace Prize winner, asserts compassionate (deep) listening moves beyond a mere interaction. Compassionate listening can be used, he claims, to help end suffering for individuals and societies. He discussed his notion of compassionate listening during an interview with Oprah Winfrey (Oprah Winfrey Network, 2012):

Deep listening is the kind of listening that can help relieve the suffering of another person. You can call it compassionate listening. You listen with only one purpose: to help him or her to empty his heart. Even if he says things that are full of wrong perceptions, full of bitterness, you are still capable of continuing to listen with compassion. Because you know that listening like that, you give that person a chance to suffer less. If you want to help him to correct his perception, you wait for another time. For now, you don’t interrupt. You don’t argue. If you do, he loses his chance. You just listen with compassion and help him to suffer less. One hour like that can bring transformation and healing.

Creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com

Practicing self-care complements compassionate listening. Compassion is simply defined as showing care to someone who suffers. Often, listening to someone who “suffers” offers a true lifeline; however, it can also be draining and exhausting to the listener. Others might say it is renewing. It is a different sort of listening and one not shared often in communication classes. One must understand, too, that not ALL situations call for compassionate or deep listening. Sometimes a paraphrase is just fine. Listening to someone you disagree with or hearing someone share a viewpoint on complex and controversial topics such as “Black Lives Matter” / “All Lives Matter” or standing/kneeling for the flag can take on a personal aspect that may thwart civil discussion. Dismissing the urge to “correct” can be difficult.

To practice “deep listening” Rome (2010) suggests one must prepare physically as well as intellectually for compassionate listening. Rome’s article (https://www.mindful.org/deep-listening/) lists several activities one can practice to increase mindful listening.

Creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com

Deep Listening involves listening, from a deep, receptive, and caring place in oneself, to deeper and often subtler levels of meaning and intention in the other person. It is listening that is generous, empathic, supportive, accurate, and trusting. Trust here does not imply agreement, but the trust that whatever others say, regardless of how well or poorly it is said, comes from something true in their experience. Deep Listening is an ongoing practice of suspending self-oriented, reactive thinking and opening one’s awareness to the unknown and unexpected (Rome, 2010).

Again, a basic approach to listening reminds us that sometimes “less is more” when it comes to “being there” for a friend or stranger. McLean (2018), as noted below, offers the following tips to facilitate listening and conversation, helping one be in the moment when things get tough:

- Set aside a special time. To have a difficult conversation or read bad news, set aside a special time when you will not be disturbed. Close the door and turn off the television, music player, and instant messaging client.

- Don’t interrupt. Keep silent while you let the other person “speak his [or her] piece.” If you are reading, make an effort to understand and digest the news without mental interruptions.

- Be nonjudgmental. Receive the message without judgment or criticism. Set aside your opinions, attitudes, and beliefs.

- Be accepting. Be open to the message being communicated, realizing that acceptance does not necessarily mean you agree with what is being said.

- Take turns. Wait until it is your turn to respond, and then measure your response in proportion to the message that was delivered to you. Reciprocal turn taking allows each person have his or her say.

- Acknowledge. Let the other person know that you have listened to the message or read it attentively.

- Understand. Be certain that you understand what your partner is saying. If you don’t understand, ask for clarification. Restate the message in your own words.

- Keep your cool. Speak your truth without blaming. A calm tone will help prevent conflict from escalating. Use “I” statements (e.g., “I felt concerned when I learned that my department is going to have a layoff”) rather than “you” statements (e.g., “You want to get rid of some of our best people”) (McLean, 2018, Section 2.6).