3.3: Perception Process - Part 3 (Interpretation)

- Page ID

- 136538

Interpretation

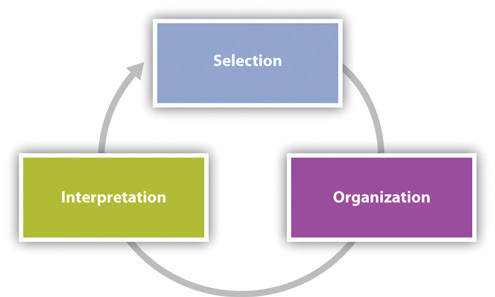

Once we have selected what to pay attention to, we organize it into a preconceived pattern or category, and then we interpret its meaning. This is essentially the outcome of our perceptions. Though all the stages in this process are important, this last stage will serve as the tangible consequence of this process. We can also note here that, as we have learned so far about perceptions, our brain is essentially trying to make sense of the world around us. One way to maintain simplicity is to confirm what we already think we know. Changing our minds can be challenging, painful, and/or complicated. Therefore, we will start with confirmation bias.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is our tendency to attend to evidence that supports preconceived notions while ignoring or disregarding evidence that is contrary to our desired reality (Gray, 2010). This can make it challenging for us to see things as they really are; instead, we see things as we are.

Let’s say you hear a rumor that your best friend, who is married, is having an affair. You know your friend. He is a great guy, a loving husband, and a devoted father. You dismiss the rumor. Of course, you could see why it seems like he might be texting more or missing regularly scheduled get-togethers, and yes, he seems to be a bit distant. But you know your friend has been very busy. A mutual friend then shows you a picture on a social media platform that seems to be your best friend and a person other than his spouse. You respond with denial and even get angry at others who ask you to talk to him, or approach him about it. Your friend would never engage in an affair. You start to look for cues to confirm your stance. He did say work was picking up; he is probably dealing with a lot of emails and meetings related to that. He tells you he has a friend from college in town and you find comfort in believing that is probably who is in the picture with him on social media.

In this scenario, your interpretation might be viewed as noble or loyal—but in other scenarios, you may be confirming biases that are harmful or inaccurate, like stereotypes, preconceived opinions, or assumptions.

As we move through this stage of the perception process, let’s continue to consider confirmation bias, noting its power to reinforce our preconceived notions, while at the same time avoiding anything that would challenge those. Let us continue to be aware of our brain’s desire to be right, even at the cost of disregarding facts.

So let us dive into the most prominent facet of interpretation: making attributions.

Attributions

Attribution is defined as “the interpretive process by which people make judgments about the causes of their own behavior and the behavior of others” (Heider, 1958, para. 3). When we engage in interpersonal communication, how we interpret messages directly influences the quality of the interaction as well as the relationship. In this section, we explore the psychological tendencies associated with perception and how they affect our communication interactions.

Fundamental Attribution Error

Fundamental attribution error is the tendency to attribute others' behavior to internal, rather than external, factors (Ross, 1977). For example, Sam is in a hurry to get to work on time and accidently blocks wheelchair access to a sidewalk when they park. When Sam gets to their car after a long shift, they see a ticket. Their initial reaction is “Those parking jerks have nothing better to do than to give me a ticket. They love ruining people’s day!” Now, let’s break this down. Sam is attributing the parking enforcement officer's action (writing a ticket) to their desire to ruin someone’s day and has labeled this officer as a jerk. There is no acknowledgement of a parking violation, the hurry to make it to work on time, or the possible inconvenience to others. We could continue and consider that the officer, while noting the violation, labeled Sam as selfish and not a law-abiding citizen. Say that a person in a wheelchair was unable to access the sidewalk and thought of Sam as a person who is uncaring of those with physical limitations. These attributions happen quickly, and they attribute a person's behavior to who that person is, rather than to external factors. Some of these assumptions—or all of them—could be true. However, we can see how miscommunication and conflict could arise quite quickly if we used attributions as the basis for our interactions with others.

Self-Serving Bias

Have you ever been driving on the freeway when your lane suddenly merges with another and you hear a loud honk? Whoa, that car came from out of nowhere! “Geeze,” you think. “Calm down, everyone is fine.” You may find yourself feeling overwhelmingly frustrated that someone got so upset when you didn’t see them in your mirrors. Later that day, you are driving and someone cuts you off. You honk loudly and think, “Pay attention to the road, you idiot!” The hypocrisy of the situation is most likely sinking in already.

Self-serving bias is essentially an attribution process that we engage in to portray ourselves in the most desirable light. Although research shows that we do this almost effortlessly for ourselves, we do not offer those same grace so easily to others.

So how does self-serving bias work, exactly? We can start by understanding where we likely place blame for undesirable behavior. Research shows us that when we are the perpetrators of undesirable behavior, we will likely place blame on external attributions (we are tired, it was an accident, it happened because someone does not like us). Conversely, when we are the victims of undesirable behavior, we place blame on the internal attributions of others (that is their character, they are inconsiderate, they did it on purpose). This was illustrated in research by Baumeister, Stillwell, and Wotman (1990), in which participants were asked to describe an experience when they angered someone else (i.e., when they were the perpetrator of an undesirable behavior) and then asked to describe an experience where someone angered them (i.e., when they were a victim of the undesirable behavior). As you might imagine, participants were quick to identify situational factors, and external attributions, as the source of their own undesirable behavior, asserting that their actions caused no lasting harm to the other. However, when describing the undesirable behavior of another, in which they were a victim, participants often cited character flaws and internal attributions, and noted the lasting damage of the interaction. These findings are quite significant if put into the context of the harm that attribution biases can have on interpersonal relationships. A good reminder here can be to check perceptions, acknowledge biases, and extend some grace to those we interact with.

Halo and Horn Effects

We have learned so far that our brains are wired to conserve energy and opt for simplicity. We also learned that initial interactions (first impressions) hold strong and for a long time. So, what happens when our first perceptions of someone are positive? What happens when they are negative? These initial perceptions stay with us for quite some time. In fact, this occurrence is so prominent that researchers have coined the terms halo and horn effects to identify them as interpersonal communication phenomena. The halo effect occurs when initial positive perceptions lead us to view later interactions as positive (Hargie, 2011). The horn effect occurs when initial negative perceptions lead us to view later interactions as negative (Hargie, 2011). Just as the metaphor suggests, you can imagine these initial interactions as creating mini halos or horns above those around you, guiding your interpretations of subsequent interactions (discussed in the section on the primacy and regency effects on page 3.2).

Halo Effect

Let’s say your sister wants the family to meet her new boyfriend, Damien. Your mom hosts at her house, and all your immediate family is in attendance. Your sister and Damien show up right on time. Damien brings flowers for your mom a bottle of wine to share and immediately asks if he should remove his shoes because they are wet from the rain outside. He introduces himself to everyone in the room and offers to help cook and set up for dinner. Damien has earned himself a halo.

The next time you meet Damien, he and your sister are running late. "This is so unlike Damien," you think to yourself. They must have gotten stuck in traffic. Damien gives you a big hug and you think, “He is so friendly.” However, for much of the night, Damien is on his phone. That halo will have you thinking he must be busy with work, or you may feel bad that he seems distracted by something else. You think you know who Damien is, based on your initial interaction with him; therefore, any negative interactions after that are attributed to external factors.

Horn Effect

If we flip the script, you could imagine another introduction where your sister and Damien show up late for dinner at your mom’s house. Damien is more reserved or shy with introductions, and perhaps he walks into the house wearing wet shoes. He does not bring anything to contribute to dinner and he certainly does not offer to help. In this scenario, perhaps Damien has earned a horn. In any subsequent meetings, that initial introduction guides your perceptions of Damien’s behavior. Say Damien offers you a hug. You might find this “out of character,” even though you have only met him once. While he is on his phone at dinner, you reconfirm that he is distant, introverted, and not particularly interested in interacting.

You can see how the initial interaction shapes how you perceive future interactions with someone new. Though you may have many subsequent interactions, research shows us that it takes some time to shake that halo or horn (Hargie, 2011).

Understanding how perceptions are formed can be a very powerful tool in helping us navigate our interpersonal relationships. Acknowledging our tendencies to make snap judgments might help us pause and reassess how accurate those judgments are.