1.1: An Introduction to Communication Theory

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 79259

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- identify and define the four communication settings

- illustrate communication as a transactional process

- explain the purposes of communication

- summarize the characteristics of communication

- explain sender-based versus receiver-based communication and what it means to be self-reflexive.

When registering for an “Introduction to Communication” class, most may wonder, “Is this just a public speaking class?” While certainly part of the field of Communication Studies, public speaking is only one of the many areas we address. A better way to consider the field of Communication Studies is to think of it as the study of oral and aural communication. We look not only at the classic public speaking setting, we also consider how we use oral communication (speaking) and aural communication (listening) to interact with those around us, to build relationships, to satisfy our own personal needs, to exchange information, to persuade others, and to work collaboratively in groups. Public speaking is but one facet of a much larger field.

Studying communication enhances our soft skills. As we prepare for a career, we are developing two sets of skills: hard skills and soft skills. Hard skills are specific to our fields, such as an accountant who needs to know how to handle credits and debits; a nurse who needs to know human anatomy and how to take a blood pressure reading; or a police officer who needs to know the law and how to use physical force appropriately and judiciously.

Soft skills are those skills that apply across the board and enhance our ability to work with others in a range of settings. These include such skills the ability to work collaboratively, to present ideas effectively in writing or speaking, to listen effectively, to think critically, and to develop and maintain healthy collegial relationships.

According to Forbes magazine, employers look for 10 core skills:

1. Ability to work in a team structure

2. Ability to make decisions and solve problems

3. Ability to communicate verbally with people inside and outside an organization

4. Ability to plan, organize and prioritize work

5. Ability to obtain and process information

6. Ability to analyze quantitative data

7. Technical knowledge related to the job

8. Proficiency with computer software programs

9. Ability to create and/or edit written reports

10. Ability to persuade and influence others (Adams, 2014).

Communication Studies addresses many of these skills, especially items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10. This course will introduce these skill areas, and additional Communication Studies classes can advance and refine those skills to an even greater degree. The ideal end result is a strong set of hard skills packaged in a strong set of soft skills; hard skills look great on a resume, and soft skills look great in an interview.

In this course, we will be addressing the three classic settings of communication studies, along with a new, emerging setting. The classic settings are Interpersonal Communication (one with one), Small Group Communication (several among several), and Public Speaking (one to many). We will also look at the newest communication setting to emerge: Computer-Mediated Communication (communication via technology).

We start by reviewing some basics of communication theory which apply to all communication, such as how communication works, perception, verbal and nonverbal communication, diversity, listening, and disclosure. After looking at this broad foundation, we will then look more deeply at some specific dynamics of each of these communication contexts.'

The Communication Settings

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal Communication is "The complex process through which people produce, interpret, and coordinate messages to create shared meanings, achieve social goals, manage their personal identities, and carry out their relationships" (Verderber, 2016). This is the everyday communication we engage in with our friends, loved ones, work colleagues, or others we encounter. Although we tend to assume this is “one-with-one,” it can be among several. So, when at a party, we are engaging in interpersonal communication with quite a few people.

We do not engage in interpersonal communication with only those we already know. Communication with anyone is an interpersonal encounter, regardless of any prior relationship. Since a range of relationship types exists, talking with a significant other is interpersonal communication, but so, too, is placing an order at McDonalds with a server, who is a stranger.

To understand why we are so driven to engage in interpersonal communication, it is important to first understand the most fundamental drive of communication: to reduce uncertainty. Humans are unique animals in that we can engage in abstract thought, taking in the world around us and converting it to mental images. As far as we know, all other animals live in a world of stimulus-response. They react instinctively to whatever is around them at the moment. If we startle a deer while walking in the woods, it will run regardless of our intent; it does not stop to think about whether we are a threat or not, it just acts.

Humans, on the other hand, use stimulus-thought-response. We sense the world around us, we think about it, we talk about it, and finally we respond to it. We respond to thought more than stimulus. According to the theory of General Semantics,

As human organisms, we have limits as to what we can experience through our senses. Given these limitations, we can never experience “all” of what is “out there” to experience…. To the degree that our reactions and responses to all forms of stimuli are automatic, or conditioned, we copy animals, like Pavlov’s dog. To the degree that our reactions and responses are more controlled, delayed, or conditional to the given situation, we exhibit our uniquely-human capabilities (Institute of General Semantics, 2012a).

Communication is the key tool we use to manage and respond to the world around us. It is our key survival tool. By connecting with other humans, we can test and assess our perceptions, our thoughts about the stimuli, to determine if our responses to those thoughts are reasonable.

The overriding goal of interpersonal communication is to reduce uncertainty by fulfilling our needs for belongingness and acceptance. Humans are deeply social creatures, getting much of our sense of personal value and worth through our interactions with those around us. Belongingness is our need to feel we fit in and belong to a group of some sort. Each of us has at least one "reference group," a collection of individuals with whom acceptance is extremely important. We spend time with these people, we talk with them, and we joke with them. We care about what they think of us because we are strongly driven to feel we belong to that group; it gives us a place to fit in and feel valued. An intimate relationship with a significant other can also give us a feeling of belongingness. The connections with a long-term partner, parents, or children can give us comfort and certainty in our lives.

Acceptance is not the same as agreement. We look for those who accept and understand who we are. Although we can disagree about specific topics or issues, the underlying human relationship is still solid and exists despite those superficial disagreements. They accept our traits, both positive and negative. They like who we are; thus, they accept us as we are, the good and the bad, not necessarily for what we do or for our successes and failures.

Because these two needs are so strong in us, being in a strange place where we know no one can be very unsettling. Consider the awkwardness we feel in a social setting where we do not know many of the others present. Most probably feel a bit lost and uncertain as to we fit in. When in such a setting, most of us will deliberately try to connect with someone to fulfill those needs, at least temporarily.

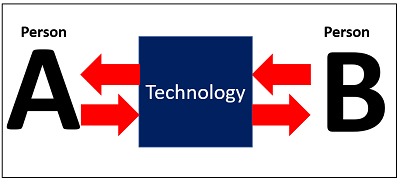

Image 5 is a simple model for interpersonal communication. The model shows both people as equal, as represented by the letters being the same size and value. The two arrows indicate both individuals communicate equally, in a balanced sense of power, both speaking and listening. This does not mean that in one specific communication encounter everything is exactly equal; rather, it means over the life of the relationship there is a sense of relative balance. For example, in virtually any marriage there will be a division of power with each partner having more power in some areas, but overall, there is a relative balance in worth, value, respect, speaking, and listening.

Small Group Communication

Small Group Communication is described as several among several. It is similar to interpersonal in that many of the dynamics of good interpersonal communication apply to several people interacting, but the primary difference is in the goal.

The goal of small group communication is task completion. However, for us to work with a group to effectively complete a task requires our basic interpersonal needs be met. The group communicates and works collaboratively most effectively to achieve a common end result when there is a sense of acceptance and belongingness among members. We are all familiar with what happens when we speak up in a group but get ignored; we quit participating.

Image 7 is a simple model for small group communication. In this model, we are looking at a task group of five people. According to Bormann and Bormann (1980), five is the ideal size for a task group. The individuals are all modeled as being of equal value and worth, and the connecting lines indicate all members participate equally with all other group members. Realistically, such equality of participation will not occur in every group meeting; however, this model represents what should occur over the life of that group.

Public Speaking

The third setting is Public Speaking. Public speaking can be described as one to many. Note for interpersonal and small group, we speak of with and among others to suggest a sense of mutual exchange and responsibility. In public speaking, however, the majority of the message is from the speaker to the audience, and as a result the speaker carries significantly more responsibility for the success of the communication event. Although the audience does retain some responsibility (attending to the message; decoding; interpreting; asking questions), it is not as equal as with interpersonal and small group. Consider a traditional, college lecture class. We easily accept the greater responsibility the instructor bears over the success of the class, especially in presenting well-developed, clearly structured lectures. The students still have their duties, such as attending class and actively listening, but there is no doubt the instructor bears more responsibility for the speaking situation.

The goal of public speaking is a transmission of information. The speaker has some sort of idea/information/position to share with the group and shares that information in this primarily unidirectional process.

The model for public speaking, image 9, is somewhat different than for the other two. First, notice the difference between the way the speaker and the audience are modeled. This represents the speaker as the primary source for the communication, having significantly more responsibility for the creation, sending, and substance of the message. Second, note the smaller, lighter arrows from the audience to the speaker. Audiences communicate with speakers via feedback, ranging from subtle (such as slight facial expression changes) to overt (such as laughter, asking questions, and applause). A good speaker uses feedback to gauge how the event is going. For example, if the audience looks bored, perhaps the speaker needs to liven things up a bit, or if they look confused, perhaps the speaker should rephrase something.

Computer-Mediated Communication

Computer-mediated communication (CMC) is communication occurring through the use of computer technologies. If we stop to consider all the ways we communicate via technology, it is mind-boggling. Everything from cell phones, texting, email, social media (like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram), discussion boards, and video conferencing all fall in this category.

Although most of those reading this text probably cannot recall a time without the internet or cell phones, in the timeline of human communication, these technologies are still very young. However, they continue to develop at a rapid pace, impacting how we connect with one another in ways we do not yet fully understand. Researchers are investigating ways technology is impacting how we communicate, form and manage relationships, work collaboratively, and even how we maintain a sense of self.

We already know constant connectivity has benefits and drawbacks. Many workplaces have now become a blend of face-to-face and online. An online student shared the first thing she does when she gets to her office is start Skype, a video-conferencing tool, and then spends her day working both with those physically present and those connecting digitally from around the nation and world. We use social media to maintain long-distance relationships which in the not-too-distant past would have faded from lack of contact. Distant family members can remain connected, sharing special events or even just daily life. Funerals, weddings, and other important ceremonies are no longer limited to those who can travel to attend. In addition to personal use, organizations can save millions in travel costs using CMC tools. Our own Minnesota State higher education system holds hundreds of meetings annually via CMC tools, saving travel costs and time away from other duties.

Even more striking is the ability of people to use social media tools to effect social change. The first, large social movement facilitated by CMC was the Arab Spring of 2011. Through the use of CMC tools like Twitter and Facebook, hundreds of thousands of disaffected citizens of several Middle Eastern countries took to the streets in protest of the status quo. In 2017, the United States saw large protests after the election of Donald Trump, protests largely organized using social media. Through this instantaneous, non-controlled mode of communication, people can find and connect with those sharing their concerns and passions.

There may be some influences of CMC that are more troubling. Attention spans may be shrinking. With Twitter’s 140 character limit, we are becoming more and more accustomed to brief, pithy messages instead of well-developed and thoughtful discourse. Managing boredom without technology may be more difficult. With the endless internet, even the slightest sense of boredom can be immediately alleviated by simply searching for something new. Since so many needs can now be fulfilled without stepping outside, those who are shy and reluctant to leave the comfort of their home can become even more isolated, with basic necessities such as groceries available for delivery via online marketplaces. Your authors have noticed a dramatic change on college campuses; while waiting for a class to start, instead of talking and developing friendships, students are silently attentive to their phones. Since we can now avoid awkward social situations by simply looking at our phones, the ability to initiate and maintain casual, acquaintance-level conversations is not needed, so the skill of “small talk” is not practiced and developed.

We have fingertip access to virtually the entire knowledge base of the human race, bringing centuries of learning to the remotest parts of our world. We have also seen the explosion of echo chambers and confirmation bias. There are so many sources of information targeted to specific political viewpoints people can choose to read or view only the news and information reinforcing the validity of their existing positions. In other words, instead of sharing common sources of information, conservatives consume conservative news and liberals consume liberal news. Since humans avoid uncertainty, echo chambers feed on our drive for information confirming our existing worldview, affirming our worldview is the “correct” view of reality.

The Communication Process |

The field of Communication Studies is far more than just public speaking. We consider the entire human communication process, looking to understand the dynamics of each of these settings to be better equipped to make thoughtful choices in managing those encounters. While each of these contexts has its own unique traits, they all share the basic communication process.

Human communication, at its best, is a process filled with complexity and hindrances. We certainly experience moments in which we feel we have really "connected" with others, but such moments are the exception to the rule. Due to the very involved and multi-faceted nature of communication, it is highly prone to breakdowns and errors. We have all experienced the frustrations of agreeing with someone about something, believing we completely understood one another, only to find later that the other person's idea of what we agreed to is totally different than our own.

By understanding the complexity of communication, we are more capable of diagnosing communication problems, and more equipped to identify and employ solutions to those problems.

Definition

Communication is the transactional process of using symbolic language to stimulate shared meaning. This definition has a lot to it, and each component needs consideration.

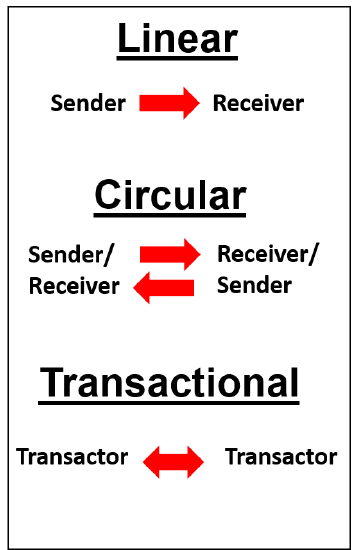

To understand the concept of transactional, we need to see where communication theory was in the past, and where are we today. At first, communication was seen as a linear process. The sender said something to the receiver. The receiver then processed the message to understand it. The problem with this approach is it only shows communication as flowing one direction; it does not account for the fact many of our messages are responses to what we heard or experienced. The linear model does not allow for nor describe the relationship of one message to another.

We then moved to a circular model which shows the sender sends a message to the receiver, and then the receiver sends a message back to the sender as feedback to what was said. In effect, the sender becomes the receiver, and the receiver becomes the sender. This model is much better in that it accounts for those related messages; however, it can also suggest all messages have a causal relationship with what was just experienced. This simply is not true. Many messages are independent of what was just experienced. If Darcy tells a joke and the class laughs, she is sending a message (the joke) and the class is sending feedback (laughter). The circular model accurately describes what happened.

However, something like clothing usually does not fit the circular model. If Lucinda is wearing a uniform to work because it is required, fits the circular model; she is wearing the uniform because of a message from her employer. Rarely, however, is our choice of clothing a response to a message; more often it is what we feel like wearing. The circular model does not account for this independence.

The linear model is too narrow, and the circular model is too broad. Today, we use the transactional model of communication. The transactional model says we have multiple messages flowing simultaneously between people. Some messages are independent, and some messages are causal (or feedback). As we interact, we sort out these messages, distinguishing feedback from independent messages.

Task-shifting comes easily to us: “we are capable of receiving, decoding, and responding to another person’s behavior, while at the same time that other person is receiving and responding to ours” (Adler, 2012). Our brains have enormous processing power, so to engage in these simultaneous tasks is quite easy.

Communication is a process, instead of a single act. A process is an event comprised of many parts, working together, with each part having a dependence on the other. Consider the complexity of a car. It works via a process of many different parts operating in concert to produce propulsion. If any one part breaks down, depending on how integral it is to the process, the whole vehicle stops moving. Communication is similar in that if a key part of the process fails, the whole thing stops working. Or, if a secondary part fails, it may keep running, but not smoothly. Either way, if one part fails, the whole process is affected.

The next part of the definition, symbolic language, requires we think about what language actually is. Whether written or spoken, language is a set of sounds or shapes to which we attach meaning. When looking at this text, students are simply looking at a series of shapes on a page. The shapes are inherently meaningless. When we speak, all we are doing is making sound and using the structures of our mouth to shape sound into certain patterns, but those sounds also are meaningless.

Although they are just shapes and sounds, they symbolize an object or concept. A symbol is using a sound or visual image to stimulate meaning. For instance, when we see the classic red circle with the diagonal line in Image 14, we know it means “don’t do” something. Through our life experiences, we learn to associate meaning with certain sounds or shapes.

The process of making those associations occurs only within the minds of the people involved; there is no such thing as truly "objective" meaning. Each of us attaches a meaning to a word that is unique to us; we each see language in our own individual way. The meanings we attach may be similar, but often those meanings can be dramatically different. Some words are far more concrete, and some are much more abstract.

Consider a word like “cat.” For most students reading this, they probably think of a four legged, feline creature that is typically kept as a pet, or, for those on farms, to kill rodents. Most of us probably picture something very similar; yet, we will also have differences. For those having a cat, perhaps they visualize their own cat. For those who like cats, they attach a positive connotation to the symbol; if they do not like cats, the connotation they attach may be far more negative. Nonetheless, since “cat” is so concrete, we have little room for misunderstanding.

Compare “cat” to “fun.” Think of the many different ways people have fun. Fun is not something we can point to. Having fun is an internal sensation based on a personal judgement, so it is highly abstract. For many, going to a Friday night party is fun, but for some, such a social setting is very uncomfortable. There are many who derive a lot of fun from cleaning the bathroom, tending to a garden, or cooking complex meals, things others may see as sheer drudgery. Clearly, the opportunity for miscommunication when using abstract language is dramatically higher than when using concrete words.

In using these written or oral symbols, our goal is to stimulate shared meaning among the participants. Suzanne selects and sends symbols to Arlene, and she hopes Arlene will attach meaning very similar to what she intended. The ideal result is what the speaker intends by her message and how the receiver interprets the message are highly similar. Unfortunately, due to the complexity of this process, the likelihood of misunderstanding far outweighs the likelihood of true shared understanding.

Since we cannot directly transfer meaning from one person to another, we must use an interpretive process to attempt to stimulate meaning. This process has several stages, all of which offer opportunity for misunderstanding:

- We select symbols that have a certain meaning for us based on our life experience.

- We translate them into sounds and shapes.

- We send them to the receiver.

- The receiver sees or hears the shapes and sounds.

- The receiver determines what discrete symbols they have seen or heard.

- The receiver attaches meaning to those symbols based on their life experiences.

As a child, many have played the game, “telephone.” In this game, the children sit in a row, and the first child says something to the second child, who then shares it with the third child, and so on until it reaches the last child. Typically, the story the last child hears is quite different than the story as it began. Note each time it went from one child to another, the story was re-translated according to each child’s understanding of language. Just like the communication process, every time the message is translated it is changed, so misunderstandings are very common.

We are not, however, bound to stay lost in this sea of multiple interpretations. As we learn more about how communication functions, we learn to monitor and manage the process far more effectively.

The final aspect of the transactional model is the idea of mutual responsibility. In communication, all participants have some responsibility for the success or failure of the communication. The person speaking has a responsibility to send a clear, organized, understandable message; and the listener has a responsibility to attend to the message, interpret it, respond to it, and if they do not understand it, to ask for clarification. Even in public speaking situations where the speaker carries a larger burden of responsibility, the audience still shares responsibility for success. A classroom is a good example of this. No matter how well a teacher teaches, if a student simply refuses to try to understand the material, the teacher cannot force the student to learn. The student must meet the teacher "half way," so to speak.

The Purposes of Communication

Since communication is so complex, a reasonable question arises: Why do we do it? Evolutionary theory tells us instinctual behaviors exist to aid in the survival and perpetuation of the species. While the specific ways we communicate are culturally determined, the drive to communicate is an innate human trait. To understand the purposes of communication, we need to begin at a very basic level.

As discussed earlier, humans live in a stimulus-thought-response world, and we use communication as the tool to manage and respond to the world around us. By connecting with other humans, we can test and assess our perceptions, our thoughts about the stimuli, to determine if our responses to those thoughts are reasonable.

In using that tool, we fulfill several needs:

1. We use communication to make sense of the world around us.

Since our actions are primarily based on how we think about the world around us, communication is the tool we use to develop, categorize, and modify these perceptions. We only have language because we have the ability to abstract, to create mental images and symbols of the external world. We can then talk about, think about, and generally manipulate our internal world to enhance our understanding of people, events, and experiences. In other words, language allows us to think.

As we process the world within our own minds (a form of intrapersonal communication), and as we interact with those around us (interpersonal communication), these internal images are tested, verified, and modified. Sharing our perceptions of the world with those around us is crucial in maintaining a sense of comfort and security that our view of the world is realistic and valid. While we do not seek this validation from everyone, we do seek it from our key reference groups. We want to know that we are seeing the world “accurately,” which actually means, “similarly to those important to me.”

2. We use communication to maintain a healthy sense of self.

Humans are inherently social creatures because we need acceptance and belongingness to feel we fit in and have worth to others. Interaction gives us a sense of how others see and value us, and as we gain a sense of value and importance from others, our sense of self-worth is validated or supported. For example, if Bev thinks her sense of humor is one of her good traits, and if others validate that perception by laughing at her jokes, her sense of self has been affirmed.

As mentioned earlier, we are not seeking acceptance from everyone; rather, we develop reference groups. A reference group is a collection of individuals with whom acceptance and belongingness is very important (Hyman, 1942). We place high value on how they respond to us, and we strive to maintain good relationships and friendships with these individuals.

3. We use communication to bind us socially.

Communication also facilitates the building of relationships. In interpersonal communication, when we use the term “relationship,” we mean it differently than commonly used. Most often, students initially assume relationship means an exclusive relationship, like intimate partners. However, within this field, a relationship is any connection we have with anyone. We have a range of relationships, from the transient, such as with a clerk at a gas station, to the intimate connection of a spouse.

Regardless of the type, a relationship is nothing but how we communicate with that person; a relationship is defined and measured by the type of communication occurring. With acquaintances, we say very little, speak about limited topics for a limited time, and there is virtually never any sort of physical relationship, except perhaps a handshake. In intimate relationships, conversations tend to be longer and over a broader range of topics, and the level of physical contact may increase. We need these connections to maintain a sense of self and to fulfill our interpersonal needs, but we also need to maintain a sense of society, of connection with others we may not know well or count among our friends. Simple acts, such as saying "hello" to the checkout person at the grocery store, or commenting on the weather with a work colleague, keep us connected. We have all experienced individuals who seem to utterly ignore us, and we usually attribute highly negative labels to them, such as "stuck up," "conceited," or "pretentious." When Keith comes to the office in the morning, it is important he engages in the litany of "good mornings" and "hellos" with colleagues as it confirms his collegial connection. A simple hello, a wave, or a smile reaffirms our sense of all being connected to each other as members of the society.

A tool we use to facilitate this connection is scripts. Scripts are socially prescribed topics and dialogues we have learned to use to engage in casual, socially necessary communication (Koerner, 2002). The most common script for those in the United States is the classic "Hi, how are you?" "I'm fine. How are you?" script. This script allows us to say a few simple phrases to fulfill our obligation to acknowledge others. This script is so strong that even in situations where we are not "fine," we will still say we are. Another example of a script is often experienced during the holidays when we encounter relatives we have not seen for a while. We may hear phrases like these (depending on age): "How are you? Boy, you've grown. How's school?" Once the script is played out, one of two tracks is usually taken: if there is a friendship with this person, the participants will branch out and extend the conversation; but if not, the script is exhausted and conversation dies. Even if the conversation dwindles, the participants have fulfilled their social obligation to connect and to demonstrate other-value. The script allows us to do so in a fairly painless, comfortable manner.

4. We use communication to share information and to influence others.

As we connect socially, we naturally run into a range of ideas, interests, expertise, and goals. Instead of having to know everything, we can communicate with others to tap into the global, human knowledge base. In our highly connected world, we can share information instantaneously; no question need go unanswered.

Education is a prime example of the information sharing function of communication. Students attend school to gain information, ideas, and perspectives from others. Students learn from teachers and other students, and teachers learn from students. If we do not know how to do something, we ask someone, we search online, or we pay an expert to do it for us.

A unique ability of humans is that we can share information across generational lines. Alfred Korzybski, founder of the theory of General Semantics, referred to this as “time-binding:”

Only humans have demonstrated the capability to build on the accumulated knowledge of prior generations. Korzybski referred to this capability as time-binding and declared it as the primary difference between humans and animals. Language and the symbolizing capabilities to record, document, and transmit information serves as the principle tool that facilitates time-binding (Institute of General Semantics, 2012b).

Humans have the unique ability to share information with those who lived before us and with those who will come after us. Oral histories have existed since the invention of language, and in some cultures the passing on of stories is of great cultural significance. With the advent of the printing press, we gained a tremendous ability to leave information for those who will come long after us. This ability to share information from generation to generation is why knowledge expands so rapidly; we learn from those before us, build on it, and then pass it on.

Not only can we exchange information, we can influence each other. We live immersed in persuasion on a variety of levels. The U.S. economic culture, and hence our whole American culture, thrives on one, simple persuasive act: advertising. Advertising encourages us to spend money, and it encourages us to spend that money in certain ways. In our democratic society, we use persuasion to influence local, state, and national policy. As a nation, we use our persuasive power to influence events worldwide.

Although numbers vary widely, Americans are exposed to an enormous amount of advertising:

- Average American sees 1,000 ads per day according to NBC special, "Sex, Buys and Advertising."

- Average U.S. citizen exposed to 32,000 ads per year Mark Dery, cited in Adbusters Quarterly.

- Number of commercial messages seen by age 40? 1,000,000 ads, according to Neil Postman (Harrington, 2012).

While we do not pay attention to all these messages, they are nonetheless an integral part of our social landscape. Persuasion is an inherent part of our cultural experience.

In addition to this broad, rather obvious use of persuasive messages, we also engage in interpersonal persuasion. With our friends we may argue about what movie to go see or where to dine. We may argue about sports teams, college, or politics. Without even realizing it, we influence our reference group members to see the world as we do, and they are doing the same to us. A simple conversation about whether a song is good or not, or whether a TV show is funny or not, is actually an interpersonal persuasion event.

We also experience intrapersonal persuasion, persuasion within ourselves. Using our abilities to think, made possible by language, we are continually weighing options and making decisions. In effect, we debate ourselves: "Should I buy it?", "Should I ask her out?", "Should I take English or Music?". We talk to ourselves in an ongoing, internal dialogue. In private, that internal dialogue may even be spoken. For example, while driving a car many of us will talk out a problem to help work through issues and make decisions. We find this intrapersonal communication helps us discern the best course of action. In effect, we engage in self-persuasion.

The Characteristics of Communication

1. Communication success is rare. One of the core tenets of the theory of General Semantics is that due to the inherent complexity and interrelatedness of the components of the communication process, there is virtually always some factor inhibiting the success of communication (The Institute of General Semantics, 2012a). Those factors can range from blatant and overwhelming, such as the individuals not even speaking the same language, to more subtle and unnoticed, such as emotions that distort and alter the message being taken in. It is hard to imagine any sort of perfect communication. Granted, we all experience moments when we feel we truly connect with another person, and we feel we are able to share ideas and emotions in a very clear and pure manner; however, those wonderful moments are few and far between. This characteristic of communication emphasizes the need for us to listen carefully, speak clearly, and take time to make sure we really understand what the other is saying.

2. Communication occurs verbally and nonverbally. We communicate using a communication package. Our communication package is anything about us that has communication value. That package is comprised of two major types of communication: verbal and nonverbal. Verbal communication consists of language (words, meaning, syntax, grammar), and nonverbal communication consists of non-language communication variables (vocal traits, gestures, posture, and many more). According to Albert Mehrabian (1981), in emotional expression, verbal communication is about 7% of our overall communication package, and nonverbal is about 93% of the overall package.

While we generally think of communication as speaking, most communication actually occurs without the use of language. Nonverbal is our primary form of communication. Consider how we use nonverbal traits to test if we believe a person is lying or not. They may say, “Nothing’s wrong,” but their body language and vocal factors may suggest they are deeply troubled. Due to the overwhelming influence of nonverbal, we virtually always see the nonverbal as a true expression of emotional state.

3. Communication is continuous. A very famous communication theorist, Paul Watzlowick, coined the phrase, "One cannot not communicate" (Watzlawick, 1967). No matter how hard we may try, we are always communicating something. Obviously we can quit speaking, but we cannot stop the myriad of nonverbal messages being sent: silence communicates; absence communicates. We all know the “silent treatment” can be a very powerful tool to express displeasure. If a student skips class or work, their absence communicates a message to the instructor or supervisor. As soon as another person even thinks of us, some sort of message is being conveyed.

Due to this ongoing nature of communication, we are also sending a blend of intentional and unintentional messages. Intentional messages are those sent deliberately and purposefully, while unintentional messages are those the sender is unaware of sending. For example, before Mark goes to a job interview, he carefully considers what to wear, rehearses answers to common questions, and even selects a pen that he believes makes him look more professional. These are intentional choices Mark is making to attempt to communicate a specific message. Once at the job interview, however, Mark may fidget with his pen, not make strong eye contact, or repeatedly clear his throat, behaviors of which he is totally unaware. These unconscious behavors may be unintentional, but since they still carry communication value, the interviewer may see Mark as nervous and lacking confidence.

4. Communication has ethical implications. Communication is a powerful tool. We know how easy it is to lie, and we have all heard of various scams that are based on lies. How we choose to communicate to others or how we choose to present information has ethical considerations of which we must be aware. According to the National Communication Association Credo for Ethical Communication:

Questions of right and wrong arise whenever people communicate. Ethical communication is fundamental to responsible thinking, decision making, and the development of relationships and communities within and across contexts, cultures, channels, and media. Moreover, ethical communication enhances human worth and dignity by fostering truthfulness, fairness, responsibility, personal integrity, and respect for self and others. We believe that unethical communication threatens the quality of all communication and consequently the well-being of individuals and the society in which we live (NCA, 2012).

Ethics is a set of standards to which we hold ourselves and others accountable. For example, most would agree lying is wrong, yet we do it every day. Sarah receives a call from someone she does not wish to speak with, so what excuse does she give? Mandy says something Brandon disagrees with, but Brandon does not voice disagreement in order to avoid a conflict. An instructor asks how many have read the assignment, and Martin raises his hand even though he did not do it. Cynthia cannot find a source for a speech, so she makes one up; after all, who is really going to know? Communication is about choice, and some of those choices are inconsistent with an ethical approach to communication.

5. Communication is culturally specific. Language varies from culture to culture. While this seems obvious when comparing Chinese to Somali to Arabic, it can also apply to the same language as used in different countries. English speakers travelling in other English-speaking countries quickly find words may be pronounced differently or have different meanings. Nonverbal communication also varies distinctly. A simple, non-threatening gesture in one culture could be the beginning of a severe conflict in another. As citizens in a highly-interconnected world in which people may move among a range of cultures, we should respect those communication variations and attempt to find ways to moderate and overcome those differences, focusing on creating connections, not exacerbating differences.

Remember too these differences can exist between co-cultures as well. Travelling around the United States we will quickly find communication differences. How the English language is used in Boston and New York is different than how it used in Alabama, or Minnesota. One of the most common topics used to illustrate these differences are words referencing soft drinks, such as Coca-Cola or Pepsi. In the Upper Midwest, “pop” is common, but other areas of the country have their own terms, such as “soft drink,” “soda,” or “coke.” The Atlantic magazine created the video below illustrating some of these differences (note: expletive at the very end of the video):

Figure:\(\PageIndex{20}\): https://youtu.be/4HLYe31MBrg

Minnesota even has rich language diversity within its own borders. A visit to a small-town café in rural Minnesota may expose us to a style of language not usually heard in a club in downtown Minneapolis. Howard Mohr’s 1987 book, How to Talk Minnesotan, takes a humorous look at these regional communication traits, identifying words, phrases, and communication patterns reflective of regional Minnesota culture.

6. Communication reflects personality. We make assumptions of what a person is like based on communication behaviors. In western cultures, we usually see outgoing people as having more eye contact, a more open posture, and generally a more expressive demeanor. Likewise, quiet or shy people may avoid eye contact, use a more closed posture, and keep emotional expression at a minimum. While we want to be careful in making these assumptions, nonetheless these are an inherent part of the perception process. As we learn cultural norms, we learn to associate behaviors with assumed personality traits. This set of assumptions aids us in making quick decisions about people and events, helping us manage the uncertainty of new encounters. The obvious danger is stereotyping, but as effective, self-reflexive communicators, we recognize this tendency and work to moderate its influence.

Sender-based versus receiver-based communication

We naturally tend to be egocentric, assuming others think as we do, use language as we do, and generally see the world as we do. Since the only head we live in is our own, it is the only actual experience we have; we cannot live as another person. This, however, leads to a problem.

Sender-based communication occurs when the sender acts in an egocentric manner, assuming the way they communicate is appropriate for everyone. A sender-based person firmly believes others see the world and think as they do. As a result, they see no need to adapt to others; after all, why change what is correct to begin with? This person will assume that once something is said, it is communicated; any failure in communication is the fault of the other person. A sender-based listener assumes how they interpret the message is how the sender intended it, not allowing for misinterpretation or misunderstandings. It is a very absolute, self-centered, and non-adaptive approach to communication.

Receiver-based communication occurs when the sender acts in a provisional manner, assuming they need to consider how best to communicate this specific message to this specific person or to this audience. They realize what works for one person or situation may not work for another. They know language interpretation varies depending on background, and concepts may have to be presented in a variety of ways depending on the receiver. Like everyone, they initially interpret the message egocentrically, but they then take a second step and ask, “Is this what the speaker intended?” They realize misunderstandings and misinterpretations are typical, and they work to offset those from the beginning.

Receiver-based communication does not restrict us from what we want to communicate; rather, it guides us to think of our receiver and then package that message in the most effective manner. We have all seen adults who seem to have no ability to talk to children; they do not know how to adapt their language to a child. A sender-based communicator has far more difficulty initiating and maintaining a range of relationships. Receiver-based communicators can move among a broader range of relationships, adapting to diversity far more effectively. As we work to improve the quality of our communication, this ability to ask, “What about the receiver?” is key. By shifting focus from ourselves to the other, we increase our ability to form messages more likely to lead to higher quality communication.

The ultimate goal of studying communication is to become self-reflexive. Being a self-reflexive communicator means thoughtfully making choices about the most appropriate communication methods for a situation. We ascertain the dynamics of the event, and we adapt our communication to work with those dynamics so as to increase the likelihood of success. We do not need to change our values, viewpoints, or beliefs; we need to learn how best to communicate with others in different situations. Consider a medical provider, such as a nurse or physician. They need to be self-reflexive to determine how best to speak to the diversity of patients they treat. They encounter varying ages, language abilities, education levels, and cultural backgrounds. By being sensitive to the need to adjust to the receiver, they can better communicate with their patients.

Key Concepts |

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Oral and Aural Communication

Four communication settings

- Interpersonal Communication

- Belongingness

- Acceptance

- Small Group Communication

- Public Speaking

- Computer-Mediated Communication

The Transactional Theory of Communication

- Definition

- Transactional

- Communication is a process

- Symbolic language

- Stimulating shared meaning

- Mutual Responsibility

The Purposes of Communication

- To makes sense of the world around us

- To maintain a healthy sense of self

- To bind us socially

- Scripts

- To share information and influence others

The Characteristics of Communication

- Success is rare

- Occurs verbally and nonverbally

- Occurs continuously

- Has ethical implications

- Culturally specific

- Reflects personality

Sender-Based versus Receiver-based Communication

- Sender-Based

- Egocentricity

- Receiver-Based

- Provisionalism

- Self-reflexiveness

References |

Adams, S. (2014, November 12). The 10 skills employers most want in 2015 graduates. Retrieved from www.forbes.com/sites/susanad...-most-want-in- 2015-graduates/#5f39eeb52511

Adler, R.B., & Rodman, G. (2012). Understanding human communication (11th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bormann, E.G., & Bormann, N.C. (1980). Effective small group communication (3rd ed.). Minneapolis,MN: Burgess Publishing Company.

Harrington School of Communication and Media (2012). STAND Lesson 1: Understanding your exposure to advertising. The University of Rhode Island. mediaeducationlab.com/stand-l...re-advertising

Hyman, H.H. (1942). The Psychology of Status. Archives of Psychology, 269, 94-102. As cited in Childers, T.L., & Rao, A.R. (September, 1992). The influence of familial and peer-based reference groups on consumer decisions. Journal of Consumer Research. Retrieved from the Carlson School of Management, http://www.csom.umn.edu/

The Institute of General Semantics (2012a). Basic Understandings. Retrieved from http://www.generalsemantics.org/the-...nderstandings/.

The Institute of General Semantics (2012b). Important terms. Retrieved from http://www.generalsemantics.org/the-...portant-terms/

Koerner, A.G. & Fitzpatrick., M.A. (2002). Toward a theory of family communication. Communication Theory 12, 70-91. Retrieved from http://www.comm.umn.edu/~akoerner.

Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages: implicit communication of emotions and attitudes. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co.

Mohr, H. (1987). How to Talk Minnesotan. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

NCA (2012). NCA credo for ethical communication. The National Communication Association. Retrieved from www.natcom.org/uploadedFiles/...munication.Pdf

Verderber, K.S., & MacGeorge, E.L. (2016). Inter-Act: Interpersonal communication, concept, skills and contexts (14th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J.H., & Jackson, D.D.(1967). Pragmatics of human communication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes (pp. 48-71). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.